Читать книгу The Lost Letter from Morocco - Adrienne Chinn - Страница 7

Chapter One

ОглавлениеLondon, England – January 2009

Addy watches the crimson poison run down the plastic tube that loops like a roller coaster through the disinfected air. Over the green vinyl arm of the chair, over her father’s old navy cable-knit jumper that she’s pulled on, until it disappears down the roll-neck to a tube inserted in her chest. She’s named it the Red Devil. Killing everything in its path. Good cells and bad cells. Hopefully more bad than good.

The chemo room is full today. The girl, Rita, lies back in her chair and watches a nurse insert a cannula into her hand. Her long curly black hair twists around her earbud wires and bunches on her shoulders where she leans against the beige vinyl. Addy grimaces and turns her face away. She raises her arms and examines the purple bruises yellowing like spilt petrol on her arm. Collapsed. Every single vein. They’ve had to insert a Hickman into the veins leading to her heart. She hides the tubes inside her bra. So much easier than the cannula. She’d recommend it to anybody.

‘Jesus fuckin’ Christ!’ Rita howls. ‘That fuckin’ hurt!’

Rita is only nineteen. Breast cancer sucks.

‘God, the lift was out again. I mean the one for normal people. Visitors aren’t allowed in the sick people’s lift, apparently. Where do they get these orderlies, anyway? Rude little bastards.’

Addy’s half-sister, Philippa, drops her Louis Vuitton sample bag onto the mottled green linoleum and dumps a stack of magazines onto Addy’s lap as she leans in to air kiss Addy’s cheeks.

‘You’re wet, Pippa.’

‘Yes. Blasted English weather.’

Philippa shrugs out of her Burberry raincoat and flaps it around, spraying Addy with the winter damp. She drapes the raincoat over the back of Addy’s chair and drags a metal-legged stool across the linoleum. She perches on the stool, her slender knees neatly together.

Philippa rifles through the magazines on Addy’s lap. She folds over a page of House & Garden and hands it to Addy.

‘I’m in it this month. That place I did for the Russians in Mayfair? God, what a trial. Your photos don’t look too shabby either.’

Addy examines the plush interiors – an artful mix of bespoke English sofas, pop art, Gio Ponti originals and Georgian antiques.

‘Well done, Pips. It’s good publicity for you.’

Philippa wrinkles her elegant nose. ‘Don’t call me that. You know I hate it. Your pictures are in House & Garden, Addy. Do you know what that means? It’s a fresh start. You should thank me. That little photo shop of yours was bogging you down. Just as well it went bust. I don’t know how you could stand doing those dreadful kiddie and doggie pictures.’

‘We can’t all be David Bailey.’

‘Well, indeed. I don’t understand why you feel so terrible about it closing. It’s a bloody recession. Everyone’s going bust. Even my dentist is downsizing, which tells you something. He’s had to sell his Porsche and buy an Audi. Not even a sports model.’

Addy stares at her sister. ‘It’s hard out there.’

‘Absolutely,’ Philippa says, missing the sarcasm in Addy’s voice. ‘There’s no shame in your business going bankrupt, so I wish you’d stop fretting. Frankly, it’s getting on my nerves.’

Addy drops the magazine into her lap and picks up Heat. She flips through the flimsy pages trying to spot a celebrity she’s heard of.

‘It’s easy for you to say, Pippa. You’ve got Alessandro’s divorce settlement to live off.’

Philippa folds her arms across her chest. ‘Money isn’t everything, Adela. Status and reputation are much more important.’ She draws her groomed eyebrows together. ‘Well, at least as important as money.’

‘I’ll tell that to the supermarket cashier next time I try to pay for my groceries with my reputation.’

Philippa takes the magazine out of Addy’s hands and places it neatly on top of a tin of Cadbury’s Roses chocolates someone has left on the metal table beside Addy’s chair.

‘I was reading that.’

‘Don’t be absurd. There’s nothing in there but tat.’ Philippa brushes a stray hair out of her eye with a pink lacquered fingernail. ‘Didn’t I tell you I’d set you on the right track, Addy? What good are strings if you can’t pull them?’

Philippa perches on the stool, straight-backed and attentive like a fashion editor in the front row of a catwalk show. Her grey tweed suit hugs her yoga’d and Pilate’d body, every dart and seam tweaked to perfection. How is it possible that they share the same DNA? Addy wonders. The pale, curvy, ginger-haired Canadian and the stylish English gazelle.

Addy taps her chest. ‘I was the one who got us the House & Garden gig, Pippa. I’m the one who sent the photos in on spec.’

Philippa’s eyebrows twitch. ‘Oh. Did you?’

‘I did.’

Philippa purses her lips, fine lines feathering up from her top lip to her nose. ‘Well, anyway, you’re finally getting somewhere with this photography lark.’ She picks up the House & Garden and pages through the article. ‘I do have a knack though, don’t I? I’m not one of Britain’s top-fifty interior designers for nothing. My psychic told me the Russians would be good for me. Thank God someone’s got money in this godforsaken recession. All it took was blood, sweat and tears.’

‘Your blood or your clients’?’

‘Mostly the curtain-maker’s this time. The builder told me they call me Bloody Philly.’

Addy shakes her head. At forty-six, Philippa is six years older, a successful interior designer, a short-lived marriage to an Italian investment banker behind her, a tidy divorce settlement in the bank. A stonking big house in Chelsea. On all the charity ball committees. In with the ‘in crowd’. Busy, busy Philippa. Nothing like herself – the gauche one at the party in a cheap dress from the vintage stall in Brick Lane and flat shoes from Russell & Bromley hanging out by the kitchen door to grab the canapés. The grit in Philippa’s oyster.

Their father, Gus, couldn’t leave Britain behind fast enough after his divorce from Philippa’s mother, Lady Estella Fitzwilliam-Powell. The ‘Ethereal Essie’ as Warhol christened her in the Sixties when she’d become a fixture at Warhol’s Factory in New York after the divorce.

Her father had told her once that he’d met Essie on a July afternoon in the Pimm’s tent at the Henley Regatta in the summer of 1962. Addy had seen pictures of him at that age – handsome in the fair-skinned, black-haired Black Irish way. Like Gene Kelly or Tyrone Power. Essie was eighteen, famous for her boyish figure and pale beauty. You could find pictures of her online now. Impossibly slender in minidresses and white go-go boots, her thick dark hair in a geometric Vidal Sassoon cut. Their father was fresh out of Trinity College with a degree in geology, the first of his working-class family to earn a degree. Philippa came along six months after the wedding. The marriage lasted a year. After the divorce, their father headed to Canada to find oil for a big multinational. By forty, Essie was dead on the bed of her rented flat in New York. Drugs overdose. Withered and desiccated. No longer ethereal.

Now their father was dead, too. Alone in his garden on the coast of Vancouver Island, on a bed of his favourite dahlias.

‘Pip, I’ve been thinking—’

‘Thinking? What do you mean, you’ve been thinking, Addy?’ Philippa waves the magazine at the plastic bag of Red Devil hanging from its drip stand. ‘You’ve got enough on your plate right now with all this palaver. Nigel’s chosen a wonderful time to run off on you. You have to stop expecting men to be there for you. They’ll always let you down.’

‘Don’t go there.’

Philippa holds up her hands. ‘Sorry.’

Philippa’s words stick into Addy like pins in a voodoo doll. She hasn’t told Philippa that she’s been scrabbling to cover Nigel’s half of the mortgage as well as her own share for the past four months while he ‘recovers from the cancer trauma’. Didn’t they say disasters come in threes? They were wrong. A break-up, a bankrupt business, cancer and her father’s heart attack – four things. More than her fair share.

Addy rubs her hand over the short red wig, reaching a finger underneath to scratch her sweaty scalp.

‘I’ve only got one more chemo session, Pippa. Then some radiotherapy for a few weeks. They told me that’s a doddle. Then Tamoxifen for five years. If I can stay clear for that long, I’m back to being a normal human being. Even the insurance companies say so. That’s assuming I’m not dead.’

‘Don’t be so dramatic.’ Philippa tosses the Heat magazine onto the metal table and prises the lid off the tin of chocolates. ‘Someone’s taken all the caramels. Sod’s law.’ She drops the lid back on and reaches into the pocket of her suit jacket, pulling out her cell phone.

‘You can’t use that in here, Pippa. It interferes with the equipment.’

Philippa slides the phone back into the pocket of her tailored grey jacket. Her body is tense with what Addy takes to be the desire to leave and get on with the job of being Bloody Philly. ‘You were saying?’

‘It’ll be the spring when the radiotherapy’s done. It’s been a long year. I’m tired.’

‘Of course you’re tired. You have cancer.’

‘I had cancer.’

Philippa gestures at the women in various stages of baldness flaked out in vinyl hospital chairs the colour of dirty plasters. ‘What’s all this? Performance art?’

Addy rolls her eyes. ‘It’s insurance. To make sure there’s nothing hanging around.’

Philippa adjusts her grey wool skirt to rest just so on her kneecap. ‘Fine. You had cancer.’ She folds her arms, her lips in the tight line that sets Addy’s teeth on edge. The lipstick is leaching into the fine lines running up to her sister’s nose. ‘What’s this big idea of yours?’

Addy clears her throat. The Red Devil has created a hunger inside her. With every drop the hunger has sharpened until she’s become ravenous for life. Time is short. You hear it all the time. But now she knows time is short. She’s not going to waste one moment longer. Faffing around with a cheating boyfriend while working in a failing photography shop. No. She’ll become the photographer she’s always dreamed of being. Travel the world and capture it in her camera. Leave her footprint on the earth before it’s too late.

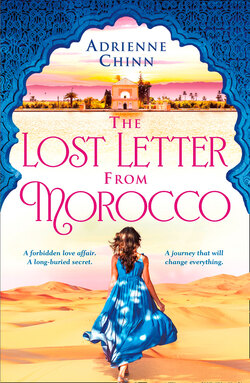

‘I’ve been thinking of working on a travel book. Julia at the photo agency thinks it’s a great idea. A “Woman’s Guide to Travelling Alone” kind of thing. On spec but if it’s good enough, Julia’s got contacts with some literary agents. Travel stories are big right now. Everyone’s trying to escape the recession one way or another.’

‘Seriously?’

Addy thrusts out her lower lip. ‘I’m not an idiot. I’ve thought this through. I need to get out of London for a while. I’m worn out. I just need to decide on a country. It needs to be exotic. And cheap.’

Philippa shudders. ‘Exotic? That sounds hot, and … unhygienic. Your career’s doing beautifully here. House & Garden. Do you know what that means? It’s a calling card. All my designer friends will be clamouring to have you photograph their work. And you want to leave on a silly jaunt to some hot, dirty, dusty, filthy fleapit? That can’t be good for you in your weakened condition. Do have some sense, Adela.’

Addy glares at her sister, knowing from countless past stand-offs that arguing is pointless. ‘Perhaps you’re right.’

‘Of course I’m right. And how on earth are you going to afford something like that? Your money’s all tied up in your flat.’

‘I can manage a few months if I’m careful with the money Dad left me. I’ll find somewhere cheap to travel to. Then, when the book sells—’

‘If it sells.’

‘—when the book sells, I’ll have some money. It might even lead to another commission.’

‘Obviously you know best. Heaven forbid you listen to your sister.’

Philippa rises and smooths her bobbed hair, a sleek sheet of brown silk. She reaches for her raincoat and rests it over her shoulders like a cape.

‘Must go now. My Russian clients are taking me to lunch at The Wolseley. They’ve just bought a house in Berkshire from some impoverished earl.’

‘I thought you hated the Russians.’

‘Don’t be daft. Of course I do. Pushy, gaudy nouveau riche with more money than sense. Which is why they’re perfect clients. I’m hardly going to let my feelings stand in the way of decorating a stately home. I’ll do a fabulous job and get you in to do the photos. I won’t even charge you a finder’s fee.’

Addy smiles feebly, wishing that Philippa wouldn’t try so hard to impose her idea of what her life should be.

‘Oh, mustn’t forget.’ Philippa picks up her sample bag and pulls out three tattered photo albums and a bulky manila envelope, adding them to the magazines on Addy’s lap. ‘It looks like you’re not the only photographer in the family. Father’s solicitor sent these to me with a stack of documents for me to sign.’ She rolls her blue eyes. ‘Like I have time. I’ve had a quick look. Tourist photos, mainly. More your kind of thing.’

Addy clutches at the albums as they slide off her lap. ‘I never knew Dad took photos.’

Philippa leans in for a quick air-kiss. ‘Who knew?’ She grimaces. ‘I hope they don’t charge the estate for the postage from Canada. Those albums weigh a ton. I’ve asked the solicitor to clear the house and sell off the contents.’

‘I might have liked to go out to Nanaimo and do that myself. I did grow up in that house.’

‘In your condition? Don’t be ridiculous. Trust me, I did you a favour. I’ve asked her to send me anything else she finds of value, though I can’t imagine there’d be much. Once the estate clears his debt, we’ll split anything left. Enough for a meal out at Pizza Hut, if we’re lucky.’

‘Were my mother’s or Dad’s Claddagh rings in with the things the solicitor sent? I haven’t seen them in ages.’

‘No, I have no idea where those are. But Dad’s pen’s in the envelope.’

Philippa gives Addy another quick air-kiss then picks her way around the other patients, carefully avoiding the nausea buckets. She raises her hand and wiggles her fingers without looking back.

Addy unties the string on the manila envelope and shakes out her father’s fat black Montblanc fountain pen with the silver nib. She flips open the faded red cover of the top album and flicks through the stiff cardboard pages. Parisian landmarks, the Coliseum in Rome, a red-sailed dhow bobbing on the water in front of the Hong Kong skyline, the evening sun silhouetting the pyramids. Images displayed like butterflies between cellophane and sticky-backed cardboard pages.

A white envelope slips out of the album, its flap dog-eared and torn. She reaches into it. More Polaroids tumble from the folds of a sheet of thin blue airmail paper, its two sides covered in her father’s blue-inked scribble.

She opens the letter:

3rd March, 1984

Zitoune, Morocco

My darling Addy,

I’m sorry it’s taken me so long to write. You know how crazy things can be when I’m over in Nigeria. I loved your letter about your initiation week at Concordia, but please tell me that was a purple wig and that you didn’t dye your lovely titian hair. Just like your mother’s.

Well, I’m not in Nigeria any more. Things are still unsettled here with the politics and all that, and with the glut of oil on the market right now, they terminated my contract early. No need to have a petroleum geologist searching for oil when they have more of it than they can sell!

The job down in Peru doesn’t start till May, so I’ve headed up to North Africa for a bit before going there. It’s dinosaur land up here, so I thought I’d do a little independent oil prospecting. Remember what I used to tell you when you were little? Where there were dinosaurs, there’s probably oil. I might try to stop by Montréal to see you when I get back before flying back to Nanaimo. Is The Old Dublin still there? They do a cracking pint of Guinness.

Addy, my darling, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking up here in the mountains. It’s a beautiful place – you must come here one day. I know how much you love the Rockies. There’s something about mountains, isn’t there? Solid and reassuring. A good place to come when life wears you down.

I know it hasn’t been easy for you since your mother died. You know there was no option but the boarding school, what with me having to travel so much for work. You made a good fist of it, though. Honour student. I never told you how proud you made me. I’m sorry for that. I’m sorry for a lot of things … I hope you know how much I love you and your sister.

There’s something I need to tell you. I’m not sure how you’ll feel about it. I’ve met someone here. Up here in a tiny village in the Moroccan mountains. You know they talk of thunderbolts? It was like that. I can’t explain it. Maybe you’ll feel it yourself one day. I hope you do.

She’s a lovely young woman from the village. She writes poetry. She has such spirit. She’s only twenty-three, Addy – nineteen years younger. I only hope

Addy peers into the envelope. Nothing. Where was the rest of the letter? What did her father hope? Who was this woman?

She looks at the Polaroids fanned out across her lap. The colours faded – the red turning into orange, the purple into pale blue, the green into yellow. The images slowly disappearing into memory. The splayed imprint of the footprint of a large bird in red clay. Something that looks like prehistoric cave carvings. An old man on a bicycle in an ancient clay-walled alleyway. A circular stone opening in a seaside wall. The shadows of a couple silhouetted on a sandy boardwalk – their loose clothing billowing about them, caught by a gust of wind. A woman’s slender brown hands holding an intricately carved wooden box inlaid with mother of pearl veneers.

Addy holds the photo up and squints at the fading image. The ring on the woman’s left ring finger. Golden hands clasping a crowned sapphire heart. A Claddagh ring. Her mother’s wedding ring. Hazel’s ring.

One by one, she turns the photographs over. Her father’s handwriting. The blue ink from his fountain pen. Dinosaur footprints, Zitoune, December 1983 – with H and … Addy squints. She can’t make out the other initial. Cave art, near Zitoune, February 1984 – with H; Alley in the Marrakech medina, March 1984 – with H; On the fortifications, Essaouira, April 1984 – with H; Le Corniche boardwalk, Casablanca, May 1984 – with H.

With H? Who’s H? Is she the woman in the letter?

Addy shifts in the chair and a final Polaroid slides out of the envelope into her lap. Its corners crushed and bent, the gloss cracking. Her father. In his forties, still fit and handsome, standing in front of a fairy-tale waterfalls. He has an arm around a woman. She’s young, with long black hair falling onto her shoulders. Her skin is a warm brown, her eyes the colour of dark chocolate.

They’re both smiling. Her father has never looked so happy. But it isn’t his smile that draws her gaze. It’s the round bump straining the fabric of the purple kaftan. Addy turns the photo over. The blue ink. The familiar impatient t’s and g’s. Zitoune waterfalls, Morocco, August 1984 – with Hanane.