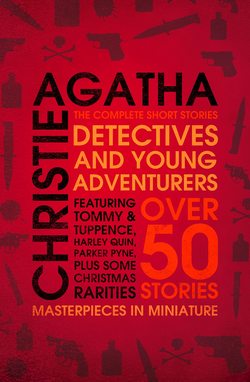

Читать книгу Detectives and Young Adventurers: The Complete Short Stories - Агата Кристи, Agatha Christie, Agatha Christie - Страница 13

ОглавлениеChapter 7

The Man in the Mist

‘The Man in the Mist’ was first published in The Sketch, 3 December 1924. Father Brown was created by G. K. Chesterton (1874–1936).

Tommy was not pleased with life. Blunt’s Brilliant Detectives had met with a reverse, distressing to their pride if not to their pockets. Called in professionally to elucidate the mystery of a stolen pearl necklace at Adlington Hall, Adlington, Blunt’s Brilliant Detectives had failed to make good. Whilst Tommy, hard on the track of a gambling Countess, was tracking her in the disguise of a Roman Catholic priest, and Tuppence was ‘getting off’ with the nephew of the house on the golf links, the local Inspector of Police had unemotionally arrested the second footman who proved to be a thief well known at headquarters, and who admitted his guilt without making any bones about it.

Tommy and Tuppence, therefore, had withdrawn with what dignity they could muster, and were at the present moment solacing themselves with cocktails at the Grand Adlington Hotel. Tommy still wore his clerical disguise.

‘Hardly a Father Brown touch, that,’ he remarked gloomily. ‘And yet I’ve got just the right kind of umbrella.’

‘It wasn’t a Father Brown problem,’ said Tuppence. ‘One needs a certain atmosphere from the start. One must be doing something quite ordinary, and then bizarre things begin to happen. That’s the idea.’

‘Unfortunately,’ said Tommy, ‘we have to return to town. Perhaps something bizarre will happen on the way to the station.’

He raised the glass he was holding to his lips, but the liquid in it was suddenly spilled, as a heavy hand smacked him on the shoulder, and a voice to match the hand boomed out words of greeting.

‘Upon my soul, it is! Old Tommy! And Mrs Tommy too. Where did you blow in from? Haven’t seen or heard anything of you for years.’

‘Why, it’s Bulger!’ said Tommy, setting down what was left of the cocktail, and turning to look at the intruder, a big square-shouldered man of thirty years of age, with a round red beaming face, and dressed in golfing kit. ‘Good old Bulger!’

‘But I say, old chap,’ said Bulger (whose real name, by the way, was Marvyn Estcourt), ‘I never knew you’d taken orders. Fancy you a blinking parson.’

Tuppence burst out laughing, and Tommy looked embarrassed. And then they suddenly became conscious of a fourth person.

A tall, slender creature, with very golden hair and very round blue eyes, almost impossibly beautiful, with an effect of really expensive black topped by wonderful ermines, and very large pearl earrings. She was smiling. And her smile said many things. It asserted, for instance, that she knew perfectly well that she herself was the thing best worth looking at, certainly in England, and possibly in the whole world. She was not vain about it in any way, but she just knew, with certainty and confidence, that it was so.

Both Tommy and Tuppence recognised her immediately. They had seen her three times in The Secret of the Heart, and an equal number of times in that other great success, Pillars of Fire, and in innumerable other plays. There was, perhaps, no other actress in England who had so firm a hold on the British public, as Miss Gilda Glen. She was reported to be the most beautiful woman in England. It was also rumoured that she was the stupidest.

‘Old friends of mine, Miss Glen,’ said Estcourt, with a tinge of apology in his voice for having presumed, even for a moment, to forget such a radiant creature. ‘Tommy and Mrs Tommy, let me introduce you to Miss Gilda Glen.’

The ring of pride in his voice was unmistakable. By merely being seen in his company, Miss Glen had conferred great glory upon him.

The actress was staring with frank interest at Tommy.

‘Are you really a priest?’ she asked. ‘A Roman Catholic priest, I mean? Because I thought they didn’t have wives.’

Estcourt went off in a boom of laughter again.

‘That’s good,’ he exploded. ‘You sly dog, Tommy. Glad he hasn’t renounced you, Mrs Tommy, with all the rest of the pomps and vanities.’

Gilda Glen took not the faintest notice of him. She continued to stare at Tommy with puzzled eyes.

‘Are you a priest?’ she demanded.

‘Very few of us are what we seem to be,’ said Tommy gently. ‘My profession is not unlike that of a priest. I don’t give absolution – but I listen to confessions – I –’

‘Don’t you listen to him,’ interrupted Estcourt. ‘He’s pulling your leg.’

‘If you’re not a clergyman, I don’t see why you’re dressed up like one,’ she puzzled. ‘That is, unless –’

‘Not a criminal flying from justice,’ said Tommy. ‘The other thing.’

‘Oh!’ she frowned, and looked at him with beautiful bewildered eyes.

‘I wonder if she’ll ever get that,’ thought Tommy to himself. ‘Not unless I put it in words of one syllable for her, I should say.’

Aloud he said:

‘Know anything about the trains back to town, Bulger? We’ve got to be pushing for home. How far is it to the station?’

‘Ten minutes’ walk. But no hurry. Next train up is the 6.35 and it’s only about twenty to six now. You’ve just missed one.’

‘Which way is it to the station from here?’

‘Sharp to the left when you turn out of the hotel. Then – let me see – down Morgan’s Avenue would be the best way, wouldn’t it?’

‘Morgan’s Avenue?’ Miss Glen started violently, and stared at him with startled eyes.

‘I know what you’re thinking of,’ said Estcourt, laughing. ‘The Ghost. Morgan’s Avenue is bounded by the cemetery on one side, and tradition has it that a policeman who met his death by violence gets up and walks on his old beat, up and down Morgan’s Avenue. A spook policeman! Can you beat it? But lots of people swear to having seen him.’

‘A policeman?’ said Miss Glen. She shivered a little. ‘But there aren’t really any ghosts, are there? I mean – there aren’t such things?’

She got up, folding her wrap tighter round her.

‘Goodbye,’ she said vaguely.

She had ignored Tuppence completely throughout, and now she did not even glance in her direction. But, over her shoulder, she threw one puzzled questioning glance at Tommy.

Just as she got to the door, she encountered a tall man with grey hair and a puffy face, who uttered an exclamation of surprise. His hand on her arm, he led her through the doorway, talking in an animated fashion.

‘Beautiful creature, isn’t she?’ said Estcourt. ‘Brains of a rabbit. Rumour has it that she’s going to marry Lord Leconbury. That was Leconbury in the doorway.’

‘He doesn’t look a very nice sort of man to marry,’ remarked Tuppence.

Estcourt shrugged his shoulders.

‘A title has a kind of glamour still, I suppose,’ he said. ‘And Leconbury is not an impoverished peer by any means. She’ll be in clover. Nobody knows where she sprang from. Pretty near the gutter, I dare say. There’s something deuced mysterious about her being down here anyway. She’s not staying at the hotel. And when I tried to find out where she was staying, she snubbed me – snubbed me quite crudely, in the only way she knows. Blessed if I know what it’s all about.’

He glanced at his watch and uttered an exclamation.

‘I must be off. Jolly glad to have seen you two again. We must have a bust in town together some night. So long.’

He hurried away, and as he did so, a page approached with a note on a salver. The note was unaddressed.

‘But it’s for you, sir,’ he said to Tommy. ‘From Miss Gilda Glen.’

Tommy tore it open and read it with some curiosity. Inside were a few lines written in a straggling untidy hand.

I’m not sure, but I think you might be able to help me. And you’ll be going that way to the station. Could you be at The White House, Morgan’s Avenue, at ten minutes past six?

Yours sincerely,

Gilda Glen.

Tommy nodded to the page, who departed, and then handed the note to Tuppence.

‘Extraordinary!’ said Tuppence. ‘Is it because she still thinks you’re a priest?’

‘No,’ said Tommy thoughtfully. ‘I should say it’s because she’s at last taken in that I’m not one. Hullo! what’s this?’

‘This,’ was a young man with flaming red hair, a pugnacious jaw, and appallingly shabby clothes. He had walked into the room and was now striding up and down muttering to himself.

‘Hell!’ said the red-haired man, loudly and forcibly. ‘That’s what I say – Hell!’

He dropped into a chair near the young couple and stared at them moodily.

‘Damn all women, that’s what I say,’ said the young man, eyeing Tuppence ferociously. ‘Oh! all right, kick up a row if you like. Have me turned out of the hotel. It won’t be for the first time. Why shouldn’t we say what we think? Why should we go about bottling up our feelings, and smirking, and saying things exactly like everyone else. I don’t feel pleasant and polite. I feel like getting hold of someone round the throat and gradually choking them to death.’

He paused.

‘Any particular person?’ asked Tuppence. ‘Or just anybody?’

‘One particular person,’ said the young man grimly.

‘This is very interesting,’ said Tuppence. ‘Won’t you tell us some more?’

‘My name’s Reilly,’ said the red-haired man. ‘James Reilly. You may have heard it. I wrote a little volume of Pacifist poems – good stuff, although I say so.’

‘Pacifist poems?’ said Tuppence.

‘Yes – why not?’ demanded Mr Reilly belligerently.

‘Oh! nothing,’ said Tuppence hastily.

‘I’m for peace all the time,’ said Mr Reilly fiercely. ‘To Hell with war. And women! Women! Did you see that creature who was trailing around here just now? Gilda Glen, she calls herself. Gilda Glen! God! how I’ve worshipped that woman. And I’ll tell you this – if she’s got a heart at all, it’s on my side. She cared once for me, and I could make her care again. And if she sells herself to that muck heap, Leconbury – well, God help her. I’d as soon kill her with my own hands.’

And on this, suddenly, he rose and rushed from the room.

Tommy raised his eyebrows.

‘A somewhat excitable gentleman,’ he murmured. ‘Well, Tuppence, shall we start?’

A fine mist was coming up as they emerged from the hotel into the cool outer air. Obeying Estcourt’s directions, they turned sharp to the left, and in a few minutes they came to a turning labelled Morgan’s Avenue.

The mist had increased. It was soft and white, and hurried past them in little eddying drifts. To their left was the high wall of the cemetery, on their right a row of small houses. Presently these ceased, and a high hedge took their place.

‘Tommy,’ said Tuppence. ‘I’m beginning to feel jumpy. The mist – and the silence. As though we were miles from anywhere.’

‘One does feel like that,’ agreed Tommy. ‘All alone in the world. It’s the effect of the mist, and not being able to see ahead of one.’

Tuppence nodded.

‘Just our footsteps echoing on the pavement. What’s that?’

‘What’s what?’

‘I thought I heard other footsteps behind us.’

‘You’ll be seeing the ghost in a minute if you work yourself up like this,’ said Tommy kindly. ‘Don’t be so nervy. Are you afraid the spook policeman will lay his hands on your shoulder?’

Tuppence emitted a shrill squeal.

‘Don’t, Tommy. Now you’ve put it into my head.’

She craned her head back over her shoulder, trying to peer into the white veil that was wrapped all round them.

‘There they are again,’ she whispered. ‘No, they’re in front now. Oh! Tommy, don’t say you can’t hear them?’

‘I do hear something. Yes, it’s footsteps behind us. Somebody else walking this way to catch the train. I wonder –’

He stopped suddenly, and stood still, and Tuppence gave a gasp.

For the curtain of mist in front of them suddenly parted in the most artificial manner, and there, not twenty feet away, a gigantic policeman suddenly appeared, as though materialised out of the fog. One minute he was not there, the next minute he was – so at least it seemed to the rather superheated imaginations of the two watchers. Then as the mist rolled back still more, a little scene appeared, as though set on a stage.

The big blue policeman, a scarlet pillar box, and on the right of the road the outlines of a white house.

‘Red, white, and blue,’ said Tommy. ‘It’s damned pictorial. Come on, Tuppence, there’s nothing to be afraid of.’

For, as he had already seen, the policeman was a real policeman. And, moreover, he was not nearly so gigantic as he had at first seemed looming up out of the mist.

But as they started forward, footsteps came from behind them. A man passed them, hurrying along. He turned in at the gate of the white house, ascended the steps, and beat a deafening tattoo upon the knocker. He was admitted just as they reached the spot where the policeman was standing staring after him.

‘There’s a gentleman seems to be in a hurry,’ commented the policeman.

He spoke in a slow reflective voice, as one whose thoughts took some time to mature.

‘He’s the sort of gentleman always would be in a hurry,’ remarked Tommy.

The policeman’s stare, slow and rather suspicious, came round to rest on his face.

‘Friend of yours?’ he demanded, and there was distinct suspicion now in his voice.

‘No,’ said Tommy. ‘He’s not a friend of mine, but I happen to know who he is. Name of Reilly.’

‘Ah!’ said the policeman. ‘Well, I’d better be getting along.’

‘Can you tell me where the White House is?’ asked Tommy.

The constable jerked his head sideways.

‘This is it. Mrs Honeycott’s.’ He paused, and added, evidently with the idea of giving them valuable information, ‘Nervous party. Always suspecting burglars is around. Always asking me to have a look around the place. Middle-aged women get like that.’

‘Middle-aged, eh?’ said Tommy. ‘Do you happen to know if there’s a young lady staying there?’

‘A young lady,’ said the policeman, ruminating. ‘A young lady. No, I can’t say I know anything about that.’

‘She mayn’t be staying here, Tommy,’ said Tuppence. ‘And anyway, she mayn’t be here yet. She could only have started just before we did.’

‘Ah!’ said the policeman suddenly. ‘Now that I call it to mind, a young lady did go in at this gate. I saw her as I was coming up the road. About three or four minutes ago it might be.’

‘With ermine furs on?’ asked Tuppence eagerly.

‘She had some kind of white rabbit round her throat,’ admitted the policeman.

Tuppence smiled. The policeman went on in the direction from which they had just come, and they prepared to enter the gate of the White House.

Suddenly, a faint, muffled cry sounded from inside the house, and almost immediately afterwards the front door opened and James Reilly came rushing down the steps. His face was white and twisted, and his eyes glared in front of him unseeingly. He staggered like a drunken man.

He passed Tommy and Tuppence as though he did not see them, muttering to himself with a kind of dreadful repetition.

‘My God! My God! Oh, my God!’

He clutched at the gatepost, as though to steady himself, and then, as though animated by sudden panic, he raced off down the road as hard as he could go in the opposite direction from that taken by the policeman.

Tommy and Tuppence stared at each other in bewilderment.

‘Well,’ said Tommy, ‘something’s happened in that house to scare our friend Reilly pretty badly.’

Tuppence drew her finger absently across the gatepost.

‘He must have put his hand on some wet red paint somewhere,’ she said idly.

‘H’m,’ said Tommy. ‘I think we’d better go inside rather quickly. I don’t understand this business.’

In the doorway of the house a white-capped maid-servant was standing, almost speechless with indignation.

‘Did you ever see the likes of that now, Father,’ she burst out, as Tommy ascended the steps. ‘That fellow comes here, asks for the young lady, rushes upstairs without how or by your leave. She lets out a screech like a wild cat – and what wonder, poor pretty dear, and straightaway he comes rushing down again, with the white face on him, like one who’s seen a ghost. What will be the meaning of it all?’

‘Who are you talking with at the front door, Ellen?’ demanded a sharp voice from the interior of the hall.

‘Here’s Missus,’ said Ellen, somewhat unnecessarily.

She drew back, and Tommy found himself confronting a grey-haired, middle-aged woman, with frosty blue eyes imperfectly concealed by pince-nez, and a spare figure clad in black with bugle trimming.

‘Mrs Honeycott?’ said Tommy. ‘I came here to see Miss Glen.’

‘Mrs Honeycott gave him a sharp glance, then went on to Tuppence and took in every detail of her appearance.

‘Oh, you did, did you?’ she said. ‘Well, you’d better come inside.’

She led the way into the hall and along it into a room at the back of the house, facing on the garden. It was a fair-sized room, but looked smaller than it was, owing to the large amount of chairs and tables crowded into it. A big fire burned in the grate, and a chintz-covered sofa stood at one side of it. The wallpaper was a small grey stripe with a festoon of roses round the top. Quantities of engravings and oil paintings covered the walls.

It was a room almost impossible to associate with the expensive personality of Miss Gilda Glen.

‘Sit down,’ said Mrs Honeycott. ‘To begin with, you’ll excuse me if I say I don’t hold with the Roman Catholic religion. Never did I think to see a Roman Catholic priest in my house. But if Gilda’s gone over to the Scarlet Woman, it’s only what’s to be expected in a life like hers – and I dare say it might be worse. She mightn’t have any religion at all. I should think more of Roman Catholics if their priests were married – I always speak my mind. And to think of those convents – quantities of beautiful young girls shut up there, and no one knowing what becomes of them – well, it won’t bear thinking about.’

Mrs Honeycott came to a full stop, and drew a deep breath.

Without entering upon a defence of the celibacy of the priesthood or the other controversial points touched upon, Tommy went straight to the point.

‘I understand, Mrs Honeycott, that Miss Glen is in this house.’

‘She is. Mind you, I don’t approve. Marriage is marriage and your husband’s your husband. As you make your bed, so you must lie on it.’

‘I don’t quite understand –’ began Tommy, bewildered.

‘I thought as much. That’s the reason I brought you in here. You can go up to Gilda after I’ve spoken my mind. She came to me – after all these years, think of it! – and asked me to help her. Wanted me to see this man and persuade him to agree to a divorce. I told her straight out I’d have nothing whatever to do with it. Divorce is sinful. But I couldn’t refuse my own sister shelter in my house, could I now?’

‘Your sister?’ exclaimed Tommy.

‘Yes, Gilda’s my sister. Didn’t she tell you?’

Tommy stared at her openmouthed. The thing seemed fantastically impossible. Then he remembered that the angelic beauty of Gilda Glen had been in evidence for many years. He had been taken to see her act as quite a small boy. Yes, it was possible after all. But what a piquant contrast. So it was from this lower middle-class respectability that Gilda Glen had sprung. How well she had guarded her secret!

‘I am not yet quite clear,’ he said. ‘Your sister is married?’

‘Ran away to be married as a girl of seventeen,’ said Mrs Honeycott succinctly. ‘Some common fellow far below her in station. And our father a reverend. It was a disgrace. Then she left her husband and went on the stage. Play-acting! I’ve never been inside a theatre in my life. I hold no truck with wickedness. Now, after all these years, she wants to divorce the man. Means to marry some big wig, I suppose. But her husband’s standing firm – not to be bullied and not to be bribed – I admire him for it.’

‘What is his name?’ asked Tommy suddenly.

‘That’s an extraordinary thing now, but I can’t remember! It’s nearly twenty years ago, you know, since I heard it. My father forbade it to be mentioned. And I’ve refused to discuss the matter with Gilda. She knows what I think, and that’s enough for her.’

‘It wasn’t Reilly, was it?’

‘Might have been. I really can’t say. It’s gone clean out of my head.’

‘The man I mean was here just now.’

‘That man! I thought he was an escaped lunatic. I’d been in the kitchen giving orders to Ellen. I’d just got back into this room, and was wondering whether Gilda had come in yet (she has a latchkey), when I heard her. She hesitated a minute or two in the hall and then went straight upstairs. About three minutes later all this tremendous rat-tatting began. I went out into the hall, and just saw a man rushing upstairs. Then there was a sort of cry upstairs, and presently down he came again and rushed out like a madman. Pretty goings on.’

Tommy rose.

‘Mrs Honeycott, let us go upstairs at once. I am afraid –’

‘What of?’

‘Afraid that you have no red wet paint in the house.’

Mrs Honeycott stared at him.

‘Of course I haven’t.’

‘That is what I feared,’ said Tommy gravely. ‘Please let us go to your sister’s room at once.’

Momentarily silenced, Mrs Honeycott led the way. They caught a glimpse of Ellen in the hall, backing hastily into one of the rooms.

Mrs Honeycott opened the first door at the top of the stairs. Tommy and Tuppence entered close behind her.

Suddenly she gave a gasp and fell back.

A motionless figure in black and ermine lay stretched on the sofa. The face was untouched, a beautiful soulless face like a mature child asleep. The wound was on the side of the head, a heavy blow with some blunt instrument had crushed in the skull. Blood was dripping slowly on to the floor, but the wound itself had long ceased to bleed . . .

Tommy examined the prostrate figure, his face very white.

‘So,’ he said at last, ‘he didn’t strangle her after all.’

‘What do you mean? Who?’ cried Mrs Honeycott. ‘Is she dead?’

‘Oh, yes, Mrs Honeycott, she’s dead. Murdered. The question is – by whom? Not that it is much of a question. Funny – for all his ranting words, I didn’t think the fellow had got it in him.’

He paused a minute, then turned to Tuppence with decision.

‘Will you go out and get a policeman, or ring up the police station from somewhere?’

Tuppence nodded. She too, was very white. Tommy led Mrs Honeycott downstairs again.

‘I don’t want there to be any mistake about this,’ he said. ‘Do you know exactly what time it was when your sister came in?’

‘Yes, I do,’ said Mrs Honeycott. ‘Because I was just setting the clock on five minutes as I have to do every evening. It loses just five minutes a day. It was exactly eight minutes past six by my watch, and that never loses or gains a second.’

Tommy nodded. That agreed perfectly with the policeman’s story. He had seen the woman with the white furs go in at the gate, probably three minutes had elapsed before he and Tuppence had reached the same spot. He had glanced at his own watch then and had noted that it was just one minute after the time of their appointment.

There was just the faint chance that some one might have been waiting for Gilda Glen in the room upstairs. But if so, he must still be hiding in the house. No one but James Reilly had left it.

He ran upstairs and made a quick but efficient search of the premises. But there was no one concealed anywhere.

Then he spoke to Ellen. After breaking the news to her, and waiting for her first lamentations and invocations to the saints to have exhausted themselves, he asked a few questions.

Had any one else come to the house that afternoon asking for Miss Glen? No one whatsoever. Had she herself been upstairs at all that evening? Yes she’d gone up at six o’clock as usual to draw the curtains – or it might have been a few minutes after six. Anyway it was just before that wild fellow came breaking the knocker down. She’d run downstairs to answer the door. And him a black-hearted murderer all the time.

Tommy let it go at that. But he still felt a curious pity for Reilly, and unwillingness to believe the worst of him. And yet there was no one else who could have murdered Gilda Glen. Mrs Honeycott and Ellen had been the only two people in the house.

He heard voices in the hall, and went out to find Tuppence and the policeman from the beat outside. The latter had produced a notebook, and a rather blunt pencil, which he licked surreptitiously. He went upstairs and surveyed the victim stolidly, merely remarking that if he was to touch anything the Inspector would give him beans. He listened to all Mrs Honeycott’s hysterical outbursts and confused explanations, and occasionally he wrote something down. His presence was calming and soothing.

Tommy finally got him alone for a minute or two on the steps outside ere he departed to telephone headquarters.

‘Look here,’ said Tommy, ‘you saw the deceased turning in at the gate, you say. Are you sure she was alone?’

‘Oh! she was alone all right. Nobody with her.’

‘And between that time and when you met us, nobody came out of the gate?’

‘Not a soul.’

‘You’d have seen them if they had?’

‘Of course I should. Nobody come out till that wild chap did.’

The majesty of the law moved portentously down the steps and paused by the white gatepost, which bore the imprint of a hand in red.

‘Kind of amateur he must have been,’ he said pityingly. ‘To leave a thing like that.’

Then he swung out into the road.

It was the day after the crime. Tommy and Tuppence were still at the Grand Hotel, but Tommy had thought it prudent to discard his clerical disguise.

James Reilly had been apprehended, and was in custody. His solicitor, Mr Marvell, had just finished a lengthy conversation with Tommy on the subject of the crime.

‘I never would have believed it of James Reilly,’ he said simply. ‘He’s always been a man of violent speech, but that’s all.’

Tommy nodded.

‘If you disperse energy in speech, it doesn’t leave you too much over for action. What I realise is that I shall be one of the principal witnesses against him. That conversation he had with me just before the crime was particularly damning. And, in spite of everything, I like the man, and if there was anyone else to suspect, I should believe him to be innocent. What’s his own story?’

The solicitor pursed up his lips.

‘He declares that he found her lying there dead. But that’s impossible, of course. He’s using the first lie that comes into his head.’

‘Because, if he happened to be speaking the truth, it would mean that the garrulous Mrs Honeycott committed the crime – and that is fantastic. Yes, he must have done it.’

‘The maid heard her cry out, remember.’

‘The maid – yes –’

Tommy was silent a moment. Then he said thoughtfully.

‘What credulous creatures we are, really. We believe evidence as though it were gospel truth. And what is it really? Only the impression conveyed to the mind by the senses – and suppose they’re the wrong impressions?’

The lawyer shrugged his shoulders.

‘Oh! we all know that there are unreliable witnesses, witnesses who remember more and more as time goes on, with no real intention to deceive.’

‘I don’t mean only that. I mean all of us – we say things that aren’t really so, and never know that we’ve done so. For instance, both you and I, without doubt, have said some time or other, “There’s the post,” when what we really meant was that we’d heard a double knock and the rattle of the letter-box. Nine times out of ten we’d be right, and it would be the post, but just possibly the tenth time it might be only a little urchin playing a joke on us. See what I mean?’

‘Ye-es,’ said Mr Marvell slowly. ‘But I don’t see what you’re driving at?’

‘Don’t you? I’m not so sure that I do myself. But I’m beginning to see. It’s like the stick, Tuppence. You remember? One end of it pointed one way – but the other end always points the opposite way. It depends whether you get hold of it by the right end. Doors open – but they also shut. People go upstairs, but they also go downstairs. Boxes shut, but they also open.’

‘What do you mean?’ demanded Tuppence.

‘It’s so ridiculously easy, really,’ said Tommy. ‘And yet it’s only just come to me. How do you know when a person’s come into the house. You hear the door open and bang to, and if you’re expecting any one to come in, you will be quite sure it is them. But it might just as easily be someone going out.’

‘But Miss Glen didn’t go out?’

‘No, I know she didn’t. But some one else did – the murderer.’

‘But how did she get in, then?’

‘She came in whilst Mrs Honeycott was in the kitchen talking to Ellen. They didn’t hear her. Mrs Honeycott went back to the drawing-room, wondered if her sister had come in and began to put the clock right, and then, as she thought, she heard her come in and go upstairs.’

‘Well, what about that? The footsteps going upstairs?’

‘That was Ellen, going up to draw the curtains. You remember, Mrs Honeycott said her sister paused before going up. That pause was just the time needed for Ellen to come out from the kitchen into the hall. She just missed seeing the murderer.’

‘But, Tommy,’ cried Tuppence. ‘The cry she gave?’

‘That was James Reilly. Didn’t you notice what a high-pitched voice he has? In moments of great emotion, men often squeal just like a woman.’

‘But the murderer? We’d have seen him?’

‘We did see him. We even stood talking to him. Do you remember the sudden way that policeman appeared? That was because he stepped out of the gate, just after the mist cleared from the road. It made us jump, don’t you remember? After all, though we never think of them as that, policemen are men just like any other men. They love and they hate. They marry . . .

‘I think Gilda Glen met her husband suddenly just outside that gate, and took him in with her to thrash the matter out. He hadn’t Reilly’s relief of violent words, remember. He just saw red – and he had his truncheon handy . . .’