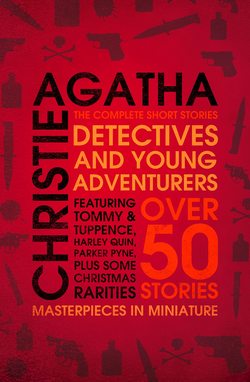

Читать книгу Detectives and Young Adventurers: The Complete Short Stories - Агата Кристи, Agatha Christie, Agatha Christie - Страница 17

ОглавлениеChapter 11

The Unbreakable Alibi

‘The Unbreakable Alibi’ was originally the last Tommy and Tuppence story, appearing in Holly Leaves (published by Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News), 1 December 1928. Inspector French was created by Freeman Wills Croft (1879–1957).

Tommy and Tuppence were busy sorting correspondence. Tuppence gave an exclamation and handed a letter across to Tommy.

‘A new client,’ she said importantly.

‘Ha!’ said Tommy. ‘What do we deduce from this letter, Watson? Nothing much, except the somewhat obvious fact that Mr – er – Montgomery Jones is not one of the world’s best spellers, thereby proving that he has been expensively educated.’

‘Montgomery Jones?’ said Tuppence. ‘Now what do I know about a Montgomery Jones? Oh, yes, I have got it now. I think Janet St Vincent mentioned him. His mother was Lady Aileen Montgomery, very crusty and high church, with gold crosses and things, and she married a man called Jones who is immensely rich.’

‘In fact the same old story,’ said Tommy. ‘Let me see, what time does this Mr M. J. wish to see us? Ah, eleven-thirty.’

At eleven-thirty precisely, a very tall young man with an amiable and ingenuous countenance entered the outer office and addressed himself to Albert, the office boy.

‘Look here – I say. Can I see Mr – er – Blunt?’

‘Have you an appointment, sir?’ said Albert.

‘I don’t quite know. Yes, I suppose I have. What I mean is, I wrote a letter –’

‘What name, sir?’

‘Mr Montgomery Jones.’

‘I will take your name in to Mr Blunt.’

He returned after a brief interval.

‘Will you wait a few minutes please, sir. Mr Blunt is engaged on a very important conference at present.’

‘Oh – er – yes – certainly,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones.

Having, he hoped, impressed his client sufficiently Tommy rang the buzzer on his desk, and Mr Montgomery Jones was ushered into the inner office by Albert.

Tommy rose to greet him, and shaking him warmly by the hand motioned towards the vacant chair.

‘Now, Mr Montgomery Jones,’ he said briskly. ‘What can we have the pleasure of doing for you?’

Mr Montgomery Jones looked uncertainly at the third occupant of the office.

‘My confidential secretary, Miss Robinson,’ said Tommy. ‘You can speak quite freely before her. I take it that this is some family matter of a delicate kind?’

‘Well – not exactly,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones.

‘You surprise me,’ said Tommy. ‘You are not in trouble of any kind yourself, I hope?’

‘Oh, rather not,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones.

‘Well,’ said Tommy, ‘perhaps you will – er – state the facts plainly.’

That, however, seemed to be the one thing that Mr Montgomery Jones could not do.

‘It’s a dashed odd sort of thing I have got to ask you,’ he said hesitatingly. ‘I – er – I really don’t know how to set about it.’

‘We never touch divorce cases,’ said Tommy.

‘Oh Lord, no,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones. ‘I don’t mean that. It is just, well – it’s a deuced silly sort of a joke. That’s all.’

‘Someone has played a practical joke on you of a mysterious nature?’ suggested Tommy.

But Mr Montgomery Jones once more shook his head.

‘Well,’ said Tommy, retiring gracefully from the position, ‘take your own time and let us have it in your own words.’

There was a pause.

‘You see,’ said Mr Jones at last, ‘it was at dinner. I sat next to a girl.’

‘Yes?’ said Tommy encouragingly.

‘She was a – oh well, I really can’t describe her, but she was simply one of the most sporting girls I ever met. She’s an Australian, over here with another girl, sharing a flat with her in. Clarges Street. She’s simply game for anything. I absolutely can’t tell you the effect that girl had on me.’

‘We can quite imagine it, Mr Jones,’ said Tuppence.

She saw clearly that if Mr Montgomery Jones’s troubles were ever to be extracted a sympathetic feminine touch was needed, as distinct from the businesslike methods of Mr Blunt.

‘We can understand,’ said Tuppence encouragingly.

‘Well, the whole thing came as an absolute shock to me,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones, ‘that a girl could well – knock you over like that. There had been another girl – in fact two other girls. One was awfully jolly and all that, but I didn’t much like her chin. She danced marvellously though, and I have known her all my life, which makes a fellow feel kind of safe, you know. And then there was one of the girls at the “Frivolity.” Frightfully amusing, but of course there would be a lot of ructions with the matter over that, and anyway I didn’t really want to marry either of them, but I was thinking about things, you know, and then – slap out of the blue – I sat next to this girl and –’

‘The whole world was changed,’ said Tuppence in a feeling voice.

Tommy moved impatiently in his chair. He was by now somewhat bored by the recital of Mr Montgomery Jones’s love affairs.

‘You put it awfully well,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones. ‘That is absolutely what it was like. Only, you know, I fancy she didn’t think much of me. You mayn’t think it, but I am not terribly clever.’

‘Oh, you mustn’t be too modest,’ said Tuppence.

‘Oh, I do realise that I am not much of a chap,’ said Mr Jones with an engaging smile. ‘Not for a perfectly marvellous girl like that. That is why I just feel I have got to put this thing through. It’s my only chance. She’s such a sporting girl that she would never go back on her word.’

‘Well, I am sure we wish you luck and all that,’ said Tuppence kindly. ‘But I don’t exactly see what you want us to do.’

‘Oh Lord,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones. ‘Haven’t I explained?’

‘No,’ said Tommy, ‘you haven’t.’

‘Well, it was like this. We were talking about detective stories. Una – that’s her name – is just as keen about them as I am. We got talking about one in particular. It all hinges on an alibi. Then we got talking about alibis and faking them. Then I said – no, she said – now which of us was it that said it?’

‘Never mind which of you it was,’ said Tuppence.

‘I said it would be a jolly difficult thing to do. She disagreed – said it only wanted a bit of brain work. We got all hot and excited about it and in the end she said, “I will make you a sporting offer. What do you bet that I can produce an alibi that nobody can shake?”‘

‘“Anything you like,” I said, and we settled it then and there. She was frightfully cocksure about the whole thing. “It’s an odds on chance for me,” she said. “Don’t be so sure of that,” I said. “Supposing you lose and I ask you for anything I like?” She laughed and said she came of a gambling family and I could.’

‘Well?’ said Tuppence as Mr Jones came to a pause and looked at her appealingly.

‘Well, don’t you see? It is up to me. It is the only chance I have got of getting a girl like that to look at me. You have no idea how sporting she is. Last summer she was out in a boat and someone bet her she wouldn’t jump overboard and swim ashore in her clothes, and she did it.’

‘It is a very curious proposition,’ said Tommy. ‘I am not quite sure I yet understand it.’

‘It is perfectly simple,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones. ‘You must be doing this sort of thing all the time. Investigating fake alibis and seeing where they fall down.’

‘Oh – er – yes, of course,’ said Tommy. ‘We do a lot of that sort of work.’

‘Someone has got to do it for me,’ said Montgomery Jones. ‘I shouldn’t be any good at that sort of thing myself. You have only got to catch her out and everything is all right. I dare say it seems rather a futile business to you, but it means a lot to me and I am prepared to pay – er – all necessary whatnots, you know.’

‘That will be all right,’ said Tuppence. ‘I am sure Mr Blunt will take this case on for you.’

‘Certainly, certainly,’ said Tommy. ‘A most refreshing case, most refreshing indeed.’

Mr Montgomery Jones heaved a sigh of relief, pulled a mass of papers from his pocket and selected one of them. ‘Here it is,’ he said. ‘She says, “I am sending you proof I was in two distinct places at one and the same time. According to one story I dined at the Bon Temps Restaurant in Soho by myself, went to the Duke’s Theatre and had supper with a friend, Mr le Marchant, at the Savoy – but I was also staying at the Castle Hotel, Torquay, and only returned to London on the following morning. You have got to find out which of the two stories is the true one and how I managed the other.”’

‘There,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones. ‘Now you see what it is that I want you to do.’

‘A most refreshing little problem,’ said Tommy. ‘Very naive.’

‘Here is Una’s photograph,’ said Mr Montgomery Jones. ‘You will want that.’

‘What is the lady’s full name?’ inquired Tommy.

‘Miss Una Drake. And her address is 180 Clarges Street.’

‘Thank you,’ said Tommy. ‘Well, we will look into the matter for you, Mr Montgomery Jones. I hope we shall have good news for you very shortly.’

‘I say, you know, I am no end grateful,’ said Mr Jones, rising to his feet and shaking Tommy by the hand. ‘It has taken an awful load off my mind.’

Having seen his client out, Tommy returned to the inner office. Tuppence was at the cupboard that contained the classic library.

‘Inspector French,’ said Tuppence.

‘Eh?’ said Tommy.

‘Inspector French, of course,’ said Tuppence. ‘He always does alibis. I know the exact procedure. We have to go over everything and check it. At first it will seem all right and then when we examine it more closely we shall find the flaw.’

‘There ought not to be much difficulty about that,’ agreed Tommy. ‘I mean, knowing that one of them is a fake to start with makes the thing almost a certainty, I should say. That is what worries me.’

‘I don’t see anything to worry about in that.’

‘I am worrying about the girl,’ said Tommy. ‘She will probably be let in to marry that young man whether she wants to or not.’

‘Darling,’ said Tuppence, ‘don’t be foolish. Women are never the wild gamblers they appear. Unless that girl was already perfectly prepared to marry that pleasant, but rather empty-headed young man, she would never have let herself in for a wager of this kind. But, Tommy, believe me, she will marry him with more enthusiasm and respect if he wins the wager than if she has to make it easy for him some other way.’

‘You do think you know about everything,’ said her husband.

‘I do,’ said Tuppence.

‘And now to examine our data,’ said Tommy, drawing the papers towards him. ‘First the photograph – h’m – quite a nice looking girl – and quite a good photograph, I should say. Clear and easily recognisable.’

‘We must get some other girls’ photographs,’ said Tuppence.

‘Why?’

‘They always do,’ said Tuppence. ‘You show four or five to waiters and they pick out the right one.’

‘Do you think they do?’ said Tommy – ‘pick out the right one, I mean.’

‘Well, they do in books,’ said Tuppence.

‘It is a pity that real life is so different from fiction,’ said Tommy. ‘Now then, what have we here? Yes, this is the London lot. Dined at the Bon Temps seven-thirty. Went to Duke’s Theatre and saw Delphiniums Blue. Counterfoil of theatre ticket enclosed. Supper at the Savoy with Mr le Marchant. We can, I suppose, interview Mr le Marchant.’

‘That tells us nothing at all,’ said Tuppence, ‘because if he is helping her to do it he naturally won’t give the show away. We can wash out anything he says now.’

‘Well, here is the Torquay end,’ went on Tommy. ‘Twelve o’clock from Paddington, had lunch in the Restaurant Car, receipted bill enclosed. Stayed at Castle Hotel for one night. Again receipted bill.’

‘I think this is all rather weak,’ said Tuppence. ‘Anyone can buy a theatre ticket, you need never go near the theatre. The girl just went to Torquay and the London thing is a fake.’

‘If so, it is rather a sitter for us,’ said Tommy. ‘Well, I suppose we might as well go and interview Mr le Marchant.’

Mr le Marchant proved to be a breezy youth who betrayed no great surprise on seeing them.

‘Una has got some little game on, hasn’t she?’ he asked. ‘You never know what that kid is up to.’

‘I understand, Mr le Marchant,’ said Tommy, ‘that Miss Drake had supper with you at the Savoy last Tuesday evening.’

‘That’s right,’ said Mr le Marchant, ‘I know it was Tuesday because Una impressed it on me at the time and what’s more she made me write it down in a little book.’

With some pride he showed an entry faintly pencilled. ‘Having supper with Una. Savoy. Tuesday 19th.’

‘Where had Miss Drake been earlier in the evening? Do you know?’

‘She had been to some rotten show called Pink Peonies or something like that. Absolute slosh, so she told me.’

‘You are quite sure Miss Drake was with you that evening?’

Mr le Marchant stared at him.

‘Why, of course. Haven’t I been telling you.’

‘Perhaps she asked you to tell us,’ said Tuppence.

‘Well, for a matter of fact she did say something that was rather dashed odd. She said – what was it now? “You think you are sitting here having supper with me, Jimmy, but really I am having supper two hundred miles away in Devonshire.” Now that was a dashed odd thing to say, don’t you think so? Sort of astral body stuff. The funny thing is that a pal of mine, Dicky Rice, thought he saw her there.’

‘Who is this Mr Rice?’

‘Oh, just a friend of mine. He had been down in Torquay staying with an aunt. Sort of old bean who is always going to die and never does. Dicky had been down doing the dutiful nephew. He said, “I saw that Australian girl one day – Una something or other. Wanted to go and talk to her, but my aunt carried me off to chat with an old pussy in a bath chair.” I said: “When was this?” and he said, “Oh, Tuesday about tea time.” I told him, of course, that he had made a mistake, but it was odd, wasn’t it? With Una saying that about Devonshire that evening?’

‘Very odd,’ said Tommy. ‘Tell me, Mr le Marchant, did anyone you know have supper near you at the Savoy?’

‘Some people called Oglander were at the next table.’

‘Do they know Miss Drake?’

‘Oh yes, they know her. They are not frightful friends or anything of that kind.’

‘Well, if there’s nothing more you can tell us, Mr le Marchant, I think we will wish you good-morning.’

‘Either that chap is an extraordinarily good liar,’ said Tommy as they reached the street, ‘or else he is speaking the truth.’

‘Yes,’ said Tuppence, ‘I have changed my opinion. I have a sort of feeling now that Una Drake was at the Savoy for supper that night.’

‘We will now go to the Bon Temps,’ said Tommy. ‘A little food for starving sleuths is clearly indicated. Let’s just get a few girls’ photographs first.’

This proved rather more difficult than was expected. Turning into a photographers and demanding a few assorted photographs, they were met with a cold rebuff.

‘Why are all the things that are so easy and simple in books so difficult in real life,’ wailed Tuppence. ‘How horribly suspicious they looked. What do you think they thought we wanted to do with the photographs? We had better go and raid Jane’s flat.’

Tuppence’s friend Jane proved of an accommodating disposition and permitted Tuppence to rummage in a drawer and select four specimens of former friends of Jane’s who had been shoved hastily in to be out of sight and mind.

Armed with this galaxy of feminine beauty they proceeded to the Bon Temps where fresh difficulties and much expense awaited them. Tommy had to get hold of each waiter in turn, tip him and then produce the assorted photographs. The result was unsatisfactory. At least three of the photographs were promising starters as having dined there last Tuesday. They then returned to the office where Tuppence immersed herself in an A.B.C.

‘Paddington twelve o’clock. Torquay three thirty-five. That’s the train and le Marchant’s friend, Mr Sago or Tapioca or something saw her there about tea time.’

‘We haven’t checked his statement, remember,’ said Tommy. ‘If, as you said to begin with, le Marchant is a friend of Una Drake’s he may have invented this story.’

‘Oh, we’ll hunt up Mr Rice,’ said Tuppence. ‘I have a kind of hunch that Mr le Marchant was speaking the truth. No, what I am trying to get at now is this. Una Drake leaves London by the twelve o’clock train, possibly takes a room at a hotel and unpacks. Then she takes a train back to town arriving in time to get to the Savoy. There is one at four-forty gets up to Paddington at nine-ten.’

‘And then?’ said Tommy.

‘And then,’ said Tuppence frowning, ‘it is rather more difficult. There is a midnight train from Paddington down again, but she could hardly take that, that would be too early.’

‘A fast car,’ suggested Tommy.

‘H’m,’ said Tuppence. ‘It is just on two hundred miles.’

‘Australians, I have always been told, drive very recklessly.’

‘Oh, I suppose it could be done,’ said Tuppence. ‘She would arrive there about seven.’

‘Are you supposing her to have nipped into her bed at the Castle Hotel without being seen? Or arriving there explaining that she had been out all night and could she have her bill, please?’

‘Tommy,’ said Tuppence, ‘we are idiots. She needn’t have gone back to Torquay at all. She has only got to get a friend to go to the hotel there and collect her luggage and pay her bill. Then you get the receipted bill with the proper date on it.’

‘I think on the whole we have worked out a very sound hypothesis,’ said Tommy. ‘The next thing to do is to catch the twelve o’clock train to Torquay tomorrow and verify our brilliant conclusions.’

Armed with a portfolio of photographs, Tommy and Tuppence duly established themselves in a first-class carriage the following morning, and booked seats for the second lunch.

‘It probably won’t be the same dining car attendants,’ said Tommy. ‘That would be too much luck to expect. I expect we shall have to travel up and down to Torquay for days before we strike the right ones.’

‘This alibi business is very trying,’ said Tuppence. ‘In books it is all passed over in two or three paragraphs. Inspector Something then boarded the train to Torquay and questioned the dining car attendants and so ended the story.’

For once, however, the young couple’s luck was in. In answer to their question the attendant who brought their bill for lunch proved to be the same one who had been on duty the preceding Tuesday. What Tommy called the ten-shilling touch then came into action and Tuppence produced the portfolio.

‘I want to know,’ said Tommy, ‘if any of these ladies had lunch on this train on Tuesday last?’

In a gratifying manner worthy of the best detective fiction the man at once indicated the photograph of Una Drake.

‘Yes, sir, I remember that lady, and I remember that it was Tuesday, because the lady herself drew attention to the fact, saying it was always the luckiest day in the week for her.’

‘So far, so good,’ said Tuppence as they returned to their compartment. ‘And we will probably find that she booked at the hotel all right. It is going to be more difficult to prove that she travelled back to London, but perhaps one of the porters at the station may remember.’

Here, however, they drew a blank, and crossing to the up platform Tommy made inquiries of the ticket collector and of various porters. After the distribution of half-crowns as a preliminary to inquiring, two of the porters picked out one of the other photographs with a vague remembrance that someone like that travelled to town by the four-forty that afternoon, but there was no identification of Una Drake.

‘But that doesn’t prove anything,’ said Tuppence as they left the station. ‘She may have travelled by that train and no one noticed her.’

‘She may have gone from the other station, from Torre.’

‘That’s quite likely,’ said Tuppence, ‘however, we can see to that after we have been to the hotel.’

The Castle Hotel was a big one overlooking the sea. After booking a room for the night and signing the register, Tommy observed pleasantly.

‘I believe you had a friend of ours staying here last Tuesday. Miss Una Drake.’

The young lady in the bureau beamed at him.

‘Oh, yes, I remember quite well. An Australian young lady, I believe.’

At a sign from Tommy, Tuppence produced the photograph.

‘That is rather a charming photograph of her, isn’t it?’ said Tuppence.

‘Oh, very nice, very nice indeed, quite stylish.’

‘Did she stay here long?’ inquired Tommy.

‘Only the one night. She went away by the express the next morning back to London. It seemed a long way to come for one night, but of course I suppose Australian ladies don’t think anything of travelling.’

‘She is a very sporting girl,’ said Tommy, ‘always having adventures. It wasn’t here, was it, that she went out to dine with some friends, went for a drive in their car afterwards, ran the car into a ditch and wasn’t able to get home till morning?’

‘Oh, no,’ said the young lady. ‘Miss Drake had dinner here in the hotel.’

‘Really,’ said Tommy, ‘are you sure of that? I mean – how do you know?’

‘Oh, I saw her.’

‘I asked because I understood she was dining with some friends in Torquay,’ explained Tommy.

‘Oh, no, sir, she dined here.’ The young lady laughed and blushed a little. ‘I remember she had on a most sweetly pretty frock. One of those new flowered chiffons all over pansies.’

‘Tuppence, this tears it,’ said Tommy when they had been shown upstairs to their room.

‘It does rather,’ said Tuppence. ‘Of course that woman may be mistaken. We will ask the waiter at dinner. There can’t be very many people here just at this time of year.’

This time it was Tuppence who opened the attack.

‘Can you tell me if a friend of mine was here last Tuesday?’ she asked the waiter with an engaging smile. ‘A Miss Drake, wearing a frock all over pansies, I believe.’ She produced a photograph. ‘This lady.’

The waiter broke into immediate smiles of recognition.

‘Yes, yes, Miss Drake, I remember her very well. She told me she came from Australia.’

‘She dined here?’

‘Yes. It was last Tuesday. She asked me if there was anything to do afterwards in the town.’

‘Yes?’

‘I told her the theatre, the Pavilion, but in the end she decided not to go and she stayed here listening to our orchestra.’

‘Oh, damn!’ said Tommy, under his breath.

‘You don’t remember what time she had dinner, do you?’ asked Tuppence.

‘She came down a little late. It must have been about eight o’clock.’

‘Damn, Blast, and Curse,’ said Tuppence as she and Tommy left the dining-room. ‘Tommy, this is all going wrong. It seemed so clear and lovely.’

‘Well, I suppose we ought to have known it wouldn’t all be plain sailing.’

‘Is there any train she could have taken after that, I wonder?’

‘Not one that would have landed her in London in time to go to the Savoy.’

‘Well,’ said Tuppence, ‘as a last hope I am going to talk to the chamber maid. Una Drake had a room on the same floor as ours.’

The chambermaid was a voluble and informative woman. Yes, she remembered the young lady quite well. That was her picture right enough. A very nice young lady, very merry and talkative. Had told her a lot about Australia and the kangaroos.

The young lady rang the bell about half-past nine and asked for her bottle to be filled and put in her bed, and also to be called the next morning at half-past seven – with coffee instead of tea.

‘You did call her and she was in her bed?’ asked Tuppence.

‘Why, yes, Ma’am, of course.’

‘Oh, I only wondered if she was doing exercises or anything,’ said Tuppence wildly. ‘So many people do in the early morning.’

‘Well, that seems cast-iron enough,’ said Tommy when the chambermaid had departed. ‘There is only one conclusion to be drawn from it. It is the London side of the thing that must be faked.’

‘Mr le Marchant must be a more accomplished liar than we thought,’ said Tuppence.

‘We have a way of checking his statements,’ said Tommy. ‘He said there were people sitting at the next table whom Una knew slightly. What was their name – Oglander, that was it. We must hunt up these Oglanders, and we ought also to make inquiries at Miss Drake’s flat in Clarges Street.’

The following morning they paid their bill and departed somewhat crestfallen.

Hunting out the Oglanders was fairly easy with the aid of the telephone book. Tuppence this-time took the offensive and assumed the character of a representative of a new illustrated paper. She called on Mrs Oglander, asking for a few details of their ‘smart’ supper party at the Savoy on Tuesday evening. These details Mrs Oglander was only too willing to supply. Just as she was leaving Tuppence added carelessly. ‘Let me see, wasn’t Miss Drake sitting at the table next to you? Is it really true that she is engaged to the Duke of Perth? You know her, of course.’

‘I know her slightly,’ said Mrs Oglander. ‘A very charming girl, I believe. Yes, she was sitting at the next table to ours with Mr le Marchant. My girls know her better than I do.’

Tuppence’s next port of call was the flat in Clarges Street. Here she was greeted by Miss Marjory Leicester, the friend with whom Miss Drake shared a flat.

‘Do tell me what all this is about?’ asked Miss Leicester plaintively. ‘Una has some deep game on and I don’t know what it is. Of course she slept here on Tuesday night.’

‘Did you see her when she came in?’

‘No, I had gone to bed. She has got her own latch key, of course. She came in about one o’clock, I believe.’

‘When did you see her?’

‘Oh, the next morning about nine – or perhaps it was nearer ten.’ As Tuppence left the flat she almost collided with a tall gaunt female who was entering.

‘Excuse me, Miss, I’m sure,’ said the gaunt female.

‘Do you work here?’ asked Tuppence.

‘Yes, Miss, I come daily.’

‘What time do you get here in the morning?’

‘Nine o’clock is my time, Miss.’

Tuppence slipped a hurried half-crown into the gaunt female’s hand.

‘Was Miss Drake here last Tuesday morning when you arrived?’

‘Why, yes, Miss, indeed she was. Fast asleep in her bed and hardly woke up when I brought her in her tea.’

‘Oh, thank you,’ said Tuppence and went disconsolately down the stairs.

She had arranged to meet Tommy for lunch in a small restaurant in Soho and there they compared notes.

‘I have seen that fellow Rice. It is quite true he did see Una Drake in the distance at Torquay.’

‘Well,’ said Tuppence, ‘we have checked these alibis all right. Here, give me a bit of paper and a pencil, Tommy. Let us put it down neatly like all detectives do.’

| 1.30 | Una Drake seen in Luncheon Car of train. |

| 4 o’clock | Arrives at Castle Hotel. |

| 5 o’clock | Seen by Mr Rice. |

| 8 o’clock | Seen dining at hotel. |

| 9.30 | Asks for hot water bottle. |

| 11.30 | Seen at Savoy with Mr le Marchant. |

| 7.30 a.m. | Called by chambermaid at Castle Hotel. |

| 9 o’clock. | Called by charwoman at flat at Clarges Street. |

They looked at each other.

‘Well, it looks to me as if Blunt’s Brilliant Detectives are beat,’ said Tommy.

‘Oh, we mustn’t give up,’ said Tuppence. ‘Somebody must be lying!’

‘The queer thing is that it strikes me nobody was lying. They all seemed perfectly truthful and straightforward.’

‘Yet there must be a flaw. We know there is. I think of all sorts of things like private aeroplanes, but that doesn’t really get us any forwarder.’

‘I am inclined to the theory of an astral body.’

‘Well,’ said Tuppence, ‘the only thing to do is to sleep on it. Your subconscious works in your sleep.’

‘H’m,’ said Tommy. ‘If your sub-conscious provides you with a perfectly good answer to this riddle by tomorrow morning, I take off my hat to it.’

They were very silent all that evening. Again and again Tuppence reverted to the paper of times. She wrote things on bits of paper. She murmured to herself, she sought perplexedly through Rail Guides. But in the end they both rose to go to bed with no faint glimmer of light on the problem.

‘This is very disheartening,’ said Tommy.

‘One of the most miserable evenings I have ever spent,’ said Tuppence.

‘We ought to have gone to a Music Hall,’ said Tommy. ‘A few good jokes about mothers-in-law and twins and bottles of beer would have done us no end of good.’

‘No, you will see this concentration will work in the end,’ said Tuppence. ‘How busy our sub-conscious will have to be in the next eight hours!’ And on this hopeful note they went to bed.

‘Well,’ said Tommy next morning. ‘Has the subconscious worked?’

‘I have got an idea,’ said Tuppence.

‘You have. What sort of an idea?’

‘Well, rather a funny idea. Not at all like anything I have ever read in detective stories. As a matter of fact it is an idea that you put into my head.’

‘Then it must be a good idea,’ said Tommy firmly. ‘Come on, Tuppence, out with it.’

‘I shall have to send a cable to verify it,’ said Tuppence. ‘No, I am not going to tell you. It’s a perfectly wild idea, but it’s the only thing that fits the facts.’

‘Well,’ said Tommy, ‘I must away to the office. A roomful of disappointed clients must not wait in vain. I leave this case in the hands of my promising subordinate.’

Tuppence nodded cheerfully.

She did not put in an appearance at the office all day. When Tommy returned that evening about half-past five it was to find a wildly exultant Tuppence awaiting him.

‘I have done it, Tommy. I have solved the mystery of the alibi. We can charge up all these half-crowns and ten-shilling notes and demand a substantial fee of our own from Mr Montgomery Jones and he can go right off and collect his girl.’

‘What is the solution?’ cried Tommy.

‘A perfectly simple one,’ said Tuppence. ‘Twins.’

‘What do you mean? – Twins?’

‘Why, just that. Of course it is the only solution. I will say you put it into my head last night talking about mothers-in-law, twins, and bottles of beer. I cabled to Australia and got back the information I wanted. Una has a twin sister, Vera, who arrived in England last Monday. That is why she was able to make this bet so spontaneously. She thought it would be a frightful rag on poor Montgomery Jones. The sister went to Torquay and she stayed in London.’

‘Do you think she’ll be terribly despondent that she’s lost?’ asked Tommy.

‘No,’ said Tuppence, ‘I don’t. I gave you my views about that before. She will put all the kudos down to Montgomery Jones. I always think respect for your husband’s abilities should be the foundation of married life.’

‘I am glad to have inspired these sentiments in you, Tuppence.’

‘It is not a really satisfactory solution,’ said Tuppence. ‘Not the ingenious sort of flaw that Inspector French would have detected.’

‘Nonsense,’ said Tommy. ‘I think the way I showed these photographs to the waiter in the restaurant was exactly like Inspector French.’

‘He didn’t have to use nearly so many half-crowns and ten-shilling notes as we seem to have done,’ said Tuppence.

‘Never mind,’ said Tommy. ‘We can charge them all up with additions to Mr Montgomery Jones. He will be in such a state of idiotic bliss that he would probably pay the most enormous bill without jibbing at it.’

‘So he should,’ said Tuppence. ‘Haven’t Blunt’s Brilliant Detectives been brilliantly successful? Oh, Tommy, I do think we are extraordinarily clever. It quite frightens me sometimes.’

‘The next case we have shall be a Roger Sheringham case, and you, Tuppence, shall be Roger Sheringham.’

‘I shall have to talk a lot,’ said Tuppence.

‘You do that naturally,’ said Tommy. ‘And now I suggest that we carry out my programme of last night and seek out a Music Hall where they have plenty of jokes about mothers-in-law, bottles of beer, and Twins.’