Читать книгу An Autobiography - Агата Кристи, Agatha Christie, Agatha Christie - Страница 5

PREFACE

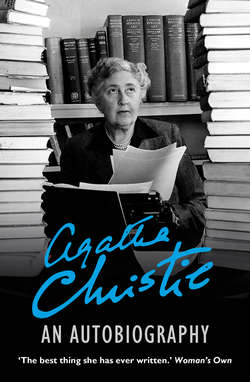

ОглавлениеAgatha Christie began to write this book in April 1950; she finished it some fifteen years later when she was 75 years old. Any book written over so long a period must contain certain repetitions and inconsistencies and these have been tidied up. Nothing of importance has been omitted, however: substantially, this is the autobiography as she would have wished it to appear.

She ended it when she was 75 because, as she put it, ‘it seems the right moment to stop. Because, as far as life is concerned, that is all there is to say.’ The last ten years of her life saw some notable triumphs–the film of Murder on the Orient Express; the continued phenomenal run of The Mousetrap; sales of her books throughout the world growing massively year by year and in the United States taking the position at the top of the best-seller charts which had for long been hers as of right in Britain and the Commonwealth; her appointment in 1971 as a Dame of the British Empire. Yet these are no more than extra laurels for achievements that in her own mind were already behind her. In 1965 she could truthfully write…‘I am satisfied. I have done what I want to do.’

Though this is an autobiography, beginning, as autobiographies should, at the beginning and going on to the time she finished writing, Agatha Christie has not allowed herself to be too rigidly circumscribed by the strait-jacket of chronology. Part of the delight of this book lies in the way in which she moves as her fancy takes her; breaking off here to muse on the incomprehensible habits of housemaids or the compensations of old age; jumping forward there because some trait in her childlike character reminds her vividly of her grandson. Nor does she feel any obligation to put everything in. A few episodes which to some might seem important–the celebrated disappearance, for example–are not mentioned, though in that particular case the references elsewhere to an earlier attack of amnesia give the clue to the true course of events. As to the rest, ‘I have remembered, I suppose, what I wanted to remember’, and though she describes her parting from her first husband with moving dignity, what she usually wants to remember are the joyful or the amusing parts of her existence.

Few people can have extracted more intense or more varied fun from life, and this book, above all, is a hymn to the joy of living.

If she had seen this book into print she would undoubtedly have wished to acknowledge many of those who had helped bring that joy into her life; above all, of course, her husband Max and her family. Perhaps it would not be out of place for us, her publishers, to acknowledge her. For fifty years she bullied, berated and delighted us; her insistence on the highest standards in every field of publishing was a constant challenge; her good-humour and zest for life brought warmth into our lives. That she drew great pleasure from her writing is obvious from these pages; what does not appear is the way in which she could communicate that pleasure to all those involved with her work, so that to publish her made business ceaselessly enjoyable. It is certain that both as an author and as a person Agatha Christie will remain unique.