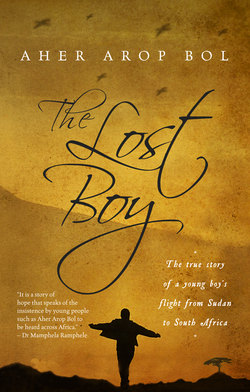

Читать книгу The lost boy - Aher Arop Bol - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 6

ОглавлениеIt was in Panyido that the animists among us – I was one of them – first came into contact with Christianity. Those in the camp who knew about Jesus started sharing their faith with those who did not. There were two denominations: Roman Catholic and Protestant. Each group marked out a chapel under the trees and brought benches for their parishioners to sit on. From the start the Protestants – with their singing – drew the larger number of followers, although the Catholics – who established a clinic to provide for the sick and injured – were also popular.

Prayer soon became an everyday way of speaking to God, of communicating to Him our sorrow and the suffering of our fatherland. Sunday services were well attended, by both those who had already committed to Christianity and those who had not. I chose to attend the Sunday prayers held by the Catholics, but did not join the catechism class.

In 1990 a baptism was organised by the Protestants. When the fateful day arrived a great number of boys gathered under the trees, singing the rousing songs they had been taught in the Dinka language to celebrate the occasion. I could not stay away – I had to go and see.

I was watching from a distance with some others when the boys were lined up under the trees. While the boys who were to be baptised were being organised, prayers were conducted by the pastors. I was fascinated and longed to be part of it. Eventually – the queue was long and moved slowly – I went up to one of the organisers and asked him if I could also be baptised. “I’ll have to find out for you,” he replied. “These boys have already completed their catechism.”

He went off to speak to some higher authority, then returned to announce that, as there wouldn’t be another baptism anytime soon, anyone who wished to be baptised that day was welcome to attend the ceremony. We could attend catechism classes afterwards, he told us. I was delighted and quickly joined the line to register.

At last it was my turn. “What’s your name?” a man asked me.

“Aher Arop,” I said.

“I mean your Christian name. A name like Abraham or Daniel or Jacob.”

“Oh, I want to be Santo,” I told him.

“No, sorry. Santo isn’t a Protestant name,” he said, shaking his head. “You can’t be Santo.”

“If I can’t be Santo, I don’t want to be baptised,” I replied.

“Look, here’s a list of names.” He read some out to me. “Just choose one of these.”

But I was adamant, and, eventually, he relented. “All right, then, you can be Santino,” he said, writing the name on a small piece of paper so that I would never forget it.

And so it came to pass that I was baptised Santino.

But who was I, actually? Aher – the name my mother had given me – or this new guy, Santino?

A boy I knew started calling “Santino, Santino!” and the others soon followed suit.

Much later, in Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya, I was to complete my catechism and be confirmed as a member of the Roman Catholic Church.