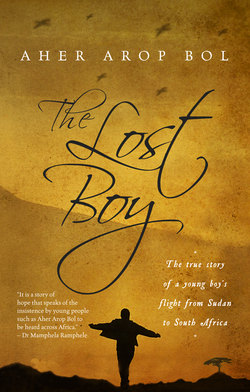

Читать книгу The lost boy - Aher Arop Bol - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 2

ОглавлениеGod alone knows how I escaped death in that camp.

My uncle Atem survived too – the uncle who had carried me all the way to the camp. He took responsibility for me and made rules I was not allowed to break. “When you are very thirsty,” he cautioned, “don’t drink more than a small mouthful when we get to water.”

He told me to drink water only when he would provide it – usually three times a day: in the morning, the afternoon and the evening. I was not allowed to drink the water our neighbours kept offering me, as he feared it might be polluted. Our water he filtered through his shirt – to trap the silvery dust in it – before storing it in a jerry can. Every morning he would ask me if I needed a drink, and then, as we had no cup, he would tilt the can for me to drink from. When food was scarce, he would forbid me to drink too much water until he had found me something to eat, and after I had eaten some maize, he would only ever allow me one sip. I used to complain, to cry out for my absent mother, but to no avail.

My uncle was also always careful when portioning out the maize. He’d give me a few kernels at a time, saving the rest for later. Often he would go without food himself, so that there would be some left for me the next day. Still, I kept whining about how hungry and thirsty I was. It was only when I was older, and had explored the surrounding countryside myself, and met the local people, that I realised how far my uncle must have walked to find villagers who would still be willing to part with a little maize, and how much effort must have gone into boiling or roasting the kernels for me. And when I saw so many die after eating too much dry maize, or drinking water with that silvery film on it, I understood that my uncle had saved my life.

Every evening, when it was a little cooler, Uncle Atem would take me and my cousins, Dut and Yaac, down to the river. We would go upstream, to avoid the crowds – the swimmers and the sick – and the pollution. I still remember how clear the water was – when you stood in it up to your waist you could see your toes and the silvery dust sparkling like diamonds on the sand below.

“Be careful!” my uncle told Dut and Yaac. “You don’t want to disturb the water when you fill the jerry can. It’ll cause that silvery stuff to rise.”

I remember how he used to wash me, and, back at the camp, cover me with a sack – the only one we had – when he put me to bed.