Читать книгу Ningyo - Alan Scott Pate - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Welcome to a beautiful, complex, and little-known world. The dolls of Edo-period Japan are marvelously textured. As objects they can be admired for their artistry, for the beautiful materials they employ, with rich silk brocades and haunting white faces, and for the delight they bring to the viewer. But dolls from this period are also historical documents, touching upon nearly every aspect of society. They speak of tastes and consumption patterns, fashions and politics of the day. They are a barometer of popular culture, reflecting trends in theater, in literature, in story and song, which occupied the hearts and minds of the people from this particularly dynamic period in Japanese history. They speak of classes and divisions, of interest groups, merchants and nobility, samurai and townsmen. They speak of religion, of long-held beliefs regarding health, infant mortality, and efforts to placate the spirits. They speak of popular festivals, some of which still thrive today, others of which have faded into oblivion. Japanese dolls are windows into a world long gone, a complex but immensely rewarding world worthy of our study and contemplation. For amidst the strange and beautiful particulars of the world of the Japanese doll are also universal truths regarding humankind's quest for expression, the inner instinct to create, to understand the society within which we live, to document our lives, to appreciate, and to convey hope.

The focus here will overwhelmingly be on Japanese dolls of a time in Japanese history known as the Edo period. Corresponding to the years 1615 to 1868, it was a remarkable time in Japanese history known for its surprising level of peace and stability after centuries of intense and violent conflict. The political hegemony established by the Tokugawa shoguns, beginning with its founder Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616), was characterized by efforts at strict political, economic, and social control. Tokugawa Japan was a closed society (sakoku), the doors of this island nation shut firmly to the outside world, limited only to trade through Dutch and Chinese merchants stationed at the remote southern fringe in the port of Nagasaki, quite distant from the capital in Edo. The national gaze was an interior one, leading to astonishing advances in all aspects of the domestic scene, from a sophisticated infrastructure and a cash economy to vibrant religious thought and a brilliant fruition in the fields of art and theater. Fashioned along nominally Confucian guidelines, Edo society was hierarchically divided into four primary classes: the ruling elite, farmers, artisans, followed lastly by merchants. The ruling classes were divided between the military classes (buke) headquartered in Edo, dominating the country politically, and the nobility (kuge) based in the former capital of Kyoto, seat of the emperor and repository of history and tradition. The farmers raised an abundance of crops, from rice, the lifeblood of the economy, to commodities such as cotton and tea, to decidedly luxury items such as silk. The artisans and craftsmen of the period benefited from a rapidly expanding economy, the broad-based appreciation of art in all of its forms, as well as massive and ongoing construction projects from the various residences of the feudal lords (daimyō), to the seemingly continuous rebuilding of the nation's largest cities which frequently succumbed to fire. The merchants were held in the lowest esteem but became an increasingly dominant force as the period progressed, with the wealth of the nation largely passing through their hands.

As time passed, the merchants were frequently far wealthier than many members of the ruling elite whose penchant for status-conferring display led to remarkable levels of debt. Shunted in the official Confucian hierarchy, the merchant class had to prudently balance their economic might with overt social discrimination and outright suppression. It was a pressure cooker in many respects, with conflicting trends, opportunities versus aspirations, economic realities versus social strictures. The cultural efflorescence of the time can be seen as partially the result of these countervailing trends. It was a beautiful by-product which produced many of the arts and cultural characteristics which we frequently use to define Japan: Kabuki, the culture of the courtesan, the art of the wood-block print known as ukiyo-e (art of the "floating world"), brilliantly dyed and decorated textiles, the kosode kimono, Zen painting, garden design, architecture, the painted folding screen, the decorative arts of lacquer work, netsuke, and inro. The development of a surprisingly rich doll culture, as well, was an unexpected outcome. No other country in the world can boast as long-lived, vibrant, and diverse a doll tradition as Japan. The artistry and quality that characterize many of Japan's fine and decorative arts are found in abundance within its various doll forms. Each of the principal types treated in this volume had its origin or fullest expression in the Edo period: gosho (palace dolls), hina (Girl's Day dolls), musha (warrior dolls), ishō (fashion dolls), and karakuri (mechanical dolls).

But before we can begin to explore the rich world of the doll of the Edo period we must first, briefly, turn the leaves of time, to look back, not in terms of centuries, but millennia, to correctly position the doll in the Japanese psyche, to establish its unique place in the earliest formative period of what was to become Japanese culture. For the doll in Japan holds layers of meaning and symbolism which anchors it more deeply in Japanese culture than its Western equivalent. Rather than a simple plaything or decorative object, the doll, as a representation of the human form, carries with it an ancient tradition of using doll-like objects as substitutes for living individuals in a wide variety of ritual practices promoting fertility, insuring contentment in the afterlife, purifying and cleansing the individual, and conferring blessings on the home. The Japanese word for doll is ningyō. Broken down into its parts, the Sino characters for "man" and "form," it literally means "human shape" or "human figure." By looking at four distinct ningyō forms from early in Japanese history, dogū, haniwa, katashiro, and nademono, we can begin to get a sense of the special and overwhelmingly symbolic role that ningyō have played in Japanese traditional culture.

Haniwa warrior figure

Kofun period, 6th century

Height 52 inches

Seattle Art Museum

Dogū

Late Jōmon period, ca. 800 BC

Height 52 inches Height 9 inches

Seattle Art Museum

EARLY NINGYŌ FORMS

The earliest ningyō date from early in Japanese history, from a time known as the Jōmon period (12000-250 BC), when the peoples who ultimately came to be known as the Japanese were first beginning to populate and establish dominance in the Japanese archipelago. Excavations from throughout the period reveal a rich pottery culture, with many clay objects primarily decorated with a cord pattern (jōmon) from which the period derives its name. Among the various pots and other utilitarian and ritual objects discovered have been a surprising quantity of doll-like forms referred to as dogū (lit. "pottery doll"). Abstract, primitive, and in some cases astonishingly futuristic, dogū are simple figures with rudimentarily formed heads, torsos, arms, and legs, all decorated with the cord patterns which were the hallmark of the era. Small in size, they average around five to nine inches high, although some large examples over twelve inches high have been discovered. The shapes and designs of the dogū varied over the long course of the Jōmon period, but archeologists such as Yamagata Mariko have noted that all of the figures are either androgynous or decidedly female, with no overtly male shapes. While most dogū are depicted standing, some are seated and appear to be giving birth, with legs splayed; others possess distended bellies with small clay balls inside. All the dogū excavated have been fractured or broken. This is not due to the ravages of time. Scholars believe that they were initially constructed in such a way as to be easily broken as part of ritual practices. Their solid clay heads, torsos, and appendages were loosely connected with small wood dowels and then covered with a lighter clay element before being decorated and fired. After being ritually broken, the parts were then distributed within the community. Although their association with fertility is generally assumed, there is no way of knowing the exact function of the dōgu. Their presence throughout all phases of Jōmon society, and the discovery of individual sites containing over a thousand figures, has, however, confirmed the importance of dogū within a ritual context. Whatever their purpose, dogū represent the first ningyō form in Japanese history, placing them within a powerfully symbolic context—a position never quite relinquished until the modern era.

In the Kofun period (AD 250-552), we find another form of ningyō, known as haniwa or "circle of clay," also being used within a ritual context. Rather than being used in fertility rituals, the haniwa were widely employed in funerary rites for the nobility where they served as substitutes for human sacrifice. We find a wide variety of figures, much like the celebrated Han and Tang dynasty funerary ceramics of continental China, including horses, small houses, ceremonial sunshades, armaments, and vessels all fashioned out of a porous red-tinted earthenware known as haji. But the most celebrated haniwa figures are those depicting human shapes. These include warriors, shamans, noblemen, women, men, nursing babies, and children. The simple but elegantly fashioned figures have done much to reveal styles of dress, personal ornamentation, hairstyles, and religious rites of the period. Part of the tumulus burial practices adopted from the Korean peninsula, these earthenware forms were placed in concentric rings around a central mounded tomb. Legend posits the origins of this practice with the tenth emperor, Suinin, during the third century. According to the Nihongi, first compiled in 720, when the brother of Emperor Suinin died, his funeral followed the then-current practice of partially burying alive the personal attendants of the deceased, leaving them with their lower extremities trapped in the earth to die a slow and agonizing death, ultimately rotting in the sun and falling victim to wild dogs and crows, as part of the interment ceremonies. Following this grisly spectacle, Suinin mandated that an alternate method be found. A potter from Izumi named Nomi no Sukune declared: "It is not good to bury living men upright at the tumulus of a prince. How can such a practice be handed down to posterity.... Henceforth let it be the law for future ages to substitute things of clay for living men and set them up at tumuli." The emperor agreed and began following this practice following the death of the Empress Hibasuhime no Mikoto. According to archeological excavations, the earliest form of haniwa were perforated jars buried inside the tumulus. Gradually, more sophisticated figures were developed, culminating in the sixth century with finely attired martial figures depicted with close-fitting helmets, plated armor, billowing trousers, swords, and bows and arrows resting atop perforated cylinders which have been set in the ground to anchor the piece. Beginning with the haniwa, we find ningyō playing the role of substitute, replacing a live individual with a doll form within a ritual context, a practice which was to be echoed in funerary and purification rituals in later eras.

In the centuries that followed the ending of the Kofun period, as tumulus-style burial practices and their associated rituals faded with the introduction of Buddhism, we find the emergence of another ningyō form known as the hito katashiro or, simply, katashiro. The katashiro were flat or tubular roughly human-shaped sculptures very rudimental in design and far more stylized than the highly realistic haniwa of the previous period. Although Buddhist sculpture from the period also reveals what levels of sophistication in carving could be achieved during the time, katashiro were extremely minimalist in execution, with crudely painted features and rough hashes for the arms and legs when depicted. Frequently wrapped in cloth or dressed in textiles, katashiro were included in numerous rituals. The katashiro form is largely considered a funerary object, being placed in the coffin along with the body and other offerings for cremation. However, the discovery of mass burials of these figures at the gates and along the walls in Nara suggest their substitution role during funerary rites had expanded into more talismanic functions, possibly to repel disease and malevolent influences. A variety of katashiro forms emerged over time, including flat pieces of wood representing a human silhouette, images in profile with separately formed arms in a marionette style, tubular sections of wood not unlike a modern baseball bat with painted features. Varying sizes of katashiro have been found in clay, stone, wood, leather, metal, paper, and straw. Documents from the succeeding Heian (794-1185) and Kamakura (1185-1333) periods describing the continued practice of using katashiro, particularly in a funeral context, attest to the longevity of this early form of ningyō and its established role in the religious rites of the period.

An evolution of the katashiro is found in the talismanic doll form known as nademono (lit. "rubbing thing"), the final in this brief survey of early ningyō forms. Over the centuries, Japan has been greatly influenced by beliefs and practices introduced from China and Korea. Native, what are now loosely termed "Shintō," beliefs and practices were modified in reaction to Buddhist beliefs and practices surrounding death, Taoist practices associated with magic and yin/yang theory, and even Korean shamanistic beliefs concerning the afterlife. Beginning in the Nara period (710-94), we find specific references to practices involving dolls and the transmission of evil elements from the person to ningyō or purging of impurities or malevolent influences through the use of the doll as a scapegoat. These practices were centered around purification rituals (oharai), most notably around the New Year, in early spring around the third month, and early summer around the fifth month. Paper dolls called nademono, very similar in shape and degree of simplicity to the katashiro, were rubbed over the body, blown upon, and then either ritually destroyed or set adrift. This was to remove accumulated negative elements from the body by transferring them into the substitute nademono. This practice was to continue uninterrupted through to the Edo period when it melded closely with the doll festival known as the Hina-matsuri. Many of these practices can be traced to similar rites in Chinese culture. Specifically, the third month third day celebrations originally known as Joshi in ancient Japan, more commonly known today as the Hina-matsuri or Girls Day doll festival, had its origins in Chinese purification rites involving ritual ablution and the burning of doll images which were considered important for insuring the health of the entire community, not just children. Similarly, the fifth month fifth day gogatsu celebration now known as Tango-no-sekku or Boy's Day, also had its origins in the Chinese practice of placing doll forms fashioned of mugwort and iris leaves on the doors of houses to ward off evil spirits. Each of these festivals will be addressed in greater depth in the book. What is important to note is that the origins and development of dolls in Japanese culture were from objects closely associated with specific rituals regarding fertility, death, health, and purification. As such, ningyō are by definition closely intertwined with these larger issues. Despite the outer camouflage of sumptuous textiles and lighthearted subject matter, at their core ningyō remain in essence powerful emblems, a buffer between this world and unseen forces, imbuing even the most fanciful of figures with a power and meaning not shared by their Western counterparts.

And so it was in 1854, at the end of the Edo period, when Commodore Mathew Perry of the United States Navy, representing the "progressive" forces of the West, came to Japan and after much saber rattling and rhetoric met with officials of the Tokugawa government, among the official gifts received from Japan was a small gosho-ningyō. It was of a young boy clothed in a simple bib holding a double gourd emblazoned with auspicious characters. This was not the only gift, nor nearly the most important exchanged on this momentous occasion—the signing of the Treaty of Kanagawa. But imagine an analogous situation, for example when US President Richard Nixon first went to China to meet with Chairman Mao Tsetung in 1972, or when President Ronald Reagan first clasped hands with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachov in 1985, if among the official gifts had been a Malibu Barbie or a Gl Joe.... Such an exchange is near inconceivable because the values, meanings, and associative qualities of a "doll" in the West are far removed from those that orbit around a Japanese ningyō. But given the historical function of the gosho-ningyō as a traditional gift, one presented to daimyō visiting the imperial court in Kyoto, combined with the multitudinous traditions surrounding ningyō in Japan and the important roles they have played for millennia in Japanese culture and psychology, such a gift was entirely natural, if somewhat perplexing to the recipients.

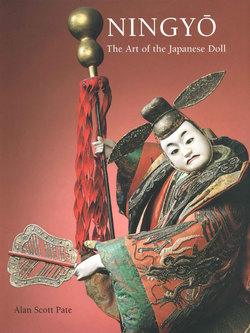

Takeda-ningyō: Takenouchi-no-sukune

Edo period, 19th century

Height 19 inches

Herring Collection

EDO NINGYŌ STYLES

Ningyō as a term applies to a vast array of figures in Japanese culture, from the minimalist Daruma tumble toy to the highly stylized and fantastic shapes of contemporary artists who explore the lighter and darker aspects of the human psyche using dolls as a medium of expression. In the Edo period, the word ningyō was used to describe an equally wide variety of forms. In reviewing historical documents, it is frequently difficult to decipher precisely what form is being referred to unless further qualifiers are employed. The terms by which many of these forms are known today are largely twentieth-century inventions, created by early Japanese collector/researchers such as Nishizawa Tekiho (1889-1965) and Kubota Beisai (1874-1937), who attempted to draw public attention to this beautiful aspect of Japanese culture. This focus of this book is restricted to five specific categories of ningyō which were both popular and played a particularly important cultural role during the Edo period, namely gosho-ningyō (palace dolls), hina-ningyō (Girls Day dolls), musha-ningyō (warrior dolls for the Boy's Day display), ishō-ningyō (fashion dolls), and harakuri-ningyō (mechanical dolls). This last category is expanded in recognition of the role that ningyō have long played in public performance forms to include iki-ningyō (living dolls which were popular exhibition pieces), bunraku-ningyō (theater puppets), Takeda-ningyō (dolls depicting figures largely drawn from Edo Kabuki performances), and uizan-ningyō which functioned as gift dolls for young Noh and kyōgen (comic theater) performers. A final chapter deals with some of the many ways ningyō tied into Edo health belief systems and practices, including hōsō-ningyō used as smallpox talismans, do-ningyō used in the study of acupuncture, and shunga-ningyō, erotic figures designed largely for onanistic purposes.

Ishō-ningyō:Fukurokuju

Edo period, 19th century

Height 13 1/2 inches

Ayervais Collection

ANATOMY OF A JAPANESE DOLL

From a distance, the elaborate textiles and gleaming white face of the traditional Japanese doll present an imposing façade—they encourage admiration rather than intimacy. Compared to a Raggedy Ann or teddy bear, Japanese dolls appear hard, stiff, and formal. Although most of this book is devoted to placing ningyō within a specific cultural context, piercing the veil of time that separates the contemporary viewer from ningyō produced during Edo-period Japan, it is helpful to approach the Japanese doll initially from a structural standpoint, to break it down into its essential elements. While construction techniques varied from category to category, for example, a solid wood gosho-ningyō compared with a fabric-clad straw-framed hina with only a wood head and hands, many of the most distinguishing aspects of the Japanese doll, regardless of category, remain consistent. The three prime elements are wood, silk textiles, and an elusive material known as gofun, which gives ningyō their brilliant white faces with their porcelaneous sheen.

MATERIALS

Wood

Japan has a long and rich tradition of carving in wood. While classical Western sculptors defined their medium in marble, the Japanese sculptor, and for all intents and purposes this refers to the Buddhist sculptors known as busshi, wood was the standard material. Though examples of dry lacquer, bronze, clay, paper, and the occasional small-scale stone piece exist, it was wood, primarily cypress (hinoki), that was dominant. Other woods used included camphor (kusu), nutmeg (kayo), sandalwood (byakudan), and cryptomeria (sugi). The heavily forested Japanese archipelago made wood a natural choice, as it was readily available and cost effective. The wood for the myriad sculptural representations of the Buddhist deities, though beautifully and sensitively carved, was not left un-adorned but was richly ornamented with metal appliqué, lacquer, pigment, and gold leaf. Inset rock crystal eyes added to the effect.

Wood also served as the principal medium for ningyō. Early records make specific mention of peach wood as particularly desirable. Peach wood had certain mytho-talismanic properties and is mentioned in early literature from the Heian period regarding puppetry. However, no examples survive from this early date to allow us to determine how widespread the practice was. For the ningyō artist of the Edo period, the lightweight, easily carved, and temperature-adaptive kiri (paulownia, Latin. Paulownia tomentosa) was the wood of choice. For gosho-ningyō and some ishō forms, kiri wood was used to carve the entire piece. Other forms tended to reserve wood for the head, hands, lower legs, and feet, resorting to more minimalist elements for the interiors. Rudimental wood framing and straw-like shavings were the most common of these interior materials. Within the hina tradition, the heads were carved into oval shapes with long tapering necks that were inserted into the stuffed cavity of the body. Within musha and some ishō forms, the heads were similarly fashioned except that the necks were typically cut square and attached to the bodies via a metal pin or wire that extended into a shoulder armature. The hands were traditionally carved separately, receiving greater or lesser sophisticated treatment. Takeda-ningyō, for example, tend to have very simple hands fashioned into rough fists when holding an object, or extended fingers which are only lightly differentiated. Kyōho-bina, an exuberant hina style dating to the eighteenth century, in contrast, are noted for their highly refined hands with long tapering pneumatic fingers bending slightly back upon themselves, reminiscent of certain Buddhist sculptures. The importance placed on the head, particularly the facial features, combined with the overall composite nature of ningyō construction, led to a division of labor in which the most skilled craftsmen or artist would be reserved for the head, while assistants crafted other elements. This is particularly true for the hina and musha categories, which witnessed such large output during the Edo period that the supply networks and manufacturing process became quite sophisticated.

(Detail) Textile dyers in Kyoto, from Rakuchu rakugai emaki (Scenes In and Around the Capital), Sumiyoshi Gukei (1631-1705),

hand scroll, color on silk,

14 inches x 12 feet.

Kombu-in, Nara

Textiles

Luxurious. Sumptuous. Rich. These are a few of the adjectives frequently encountered in the descriptions of the textiles adorning Japanese dolls. Employing the latest textile technology of their day, the best ningyō artisans clothed their creations in alternatively spectacular (another adjective) silken brocades with bold patterns and design elements or simple and understated compound woven and figured silks that reflected not only the shifting tastes of the period but also frequently aided in the identification of the dolls themselves. In addition to greatly enhancing the beauty and the appeal of ningyō, textiles were also used in structural ways. Stiff brocades frequently served as a shell holding together loosely assembled elements in certain hina, musha, and ishō forms. White silk was used both to wrap the bamboo and the wood dowels used in the construction of amagatsu-ningyō and to shape the cotton or silk wadding-stuffed figure of the hōko. Textiles were also used to hide the joints and working mechanisms of certain types of mechanical gosho forms. Padded fabrics, typically silk crepe, were used to protect the upper arm portions of certain ningyō that used wires to attach the arms to the body. Small round fabric patches were used to secure and mask dowel hinges used in a number of mitsuore (triple-jointed) ningyō.

Although cotton and ramie were commonly used in day-to-day textiles, silk was the fabric of choice for those who could afford it. Sumptuary laws, however, greatly restricted the use of silk and its various forms, limiting the use of more sophisticated weaves and decorating techniques in clothing to the upper classes. Although ningyō were frequently subjected to sumptuary regulations as well, examples from the period sport clothing featuring a wide variety of woven silk textiles, including pongee, satin, gauze, crepe, velvet, brocades of various descriptions, and twill, along with a wide variety of decorative techniques, including gold and silk thread embroidery and various dyeing techniques. Silk was very much the defining fabric for ningyō and, although some examples are clothed with asa (ramie) or feature cotton velvet details, all the textiles featured in this volume are silk. Japanese textile history is an immensely rich and entirely too broad a topic to cover here. It is also a tradition heavily steeped in technical vocabulary referring to not only the base thread material, but to the weaving structures and decorative techniques. To help clarify the discussion to follow, it will be helpful to the reader to review the four most essential and frequently discussed textile elements, namely kinran (brocades employing gold-backed paper threads), patterned weaves, chirimen (silk crepe), and birōdo (velvet).

Kinran refers to a supplementary brocade weaving technique imported originally from China which employs strips of paper backed with gold leaf which are then woven into the fabric to form discontinuous weft patterns. Patterns created from kinran varied from elaborate roundels of dragons chasing flaming pearls, to floral elements, to more geometric designs. The light-reflective qualities of the gold kinran and silver ginran made textiles created in this manner highly desirable. Kinran brocades were employed extensively in the vestments for Buddhist priests and altar hangings, Noh and Kabuki costumes, as well as an array of luxury textiles for the upper classes. Up until the fifteenth century, kinran textiles were imported from China at great expense, limiting their use and availability in Japan. Once Japanese weavers were able to master the techniques involved in its manufacture, kinran became more affordable and its use more widespread. This textile form found wonderful expression in the costuming for ningyō of all categories, conveying an added sense of beauty and luxury, a quality referred to as kekkō, a word that was frequently used in government sumptuary regulations restricting the use of kinran and other luxury textiles. The government, in keeping with the Confucian ethic of frugality and keeping ones place, advocated ningyō that were more karoku, meaning "light" or "simple."

Not all textile patterning was done through the use of brocade, supplemental embroidery, or dyeing. A long-standing tradition dating to early court practices is the use of compound weaves to create subtly patterned fabrics. Many of the patterns employed by the nobility were restricted and could not be employed outside of court circles without permission. Some of these early designs which are frequently encountered in ningyō textiles include the kikkō (tortoiseshell) pattern with its mosaic of hexagonal shapes, the hanabishi (diamond flower) pattern, the kani-arare (checkerboard) pattern, and the tatewaku (undulating line) pattern. By the Edo period, with the advent of more sophisticated patterning techniques, the early restrictions regarding these designs were largely moot and they were employed extensively in ningyō textiles. Compound weave textiles were used to their greatest effect in hina-ningyō, particularly in a subcategory known as yūsoku-bina which attempted to closely emulate the textiles worn by the nobility.

Chirimen is a silk crepe employed in many of the ningyō presented in this volume, whether as an outer fabric on the primary garment, employed in inner layers, or used as an accent element.

The highly textured surface of the silk crepe is achieved through the extreme twisting of either the warp or the weft threads. Chirimen is a version of crepe with a particular variation in the twists of the weft. Like kinran, it was initially imported from China until Japanese weavers mastered its production, becoming particularly popular as a base material for dyeing in the early part of the Edo period. Frequently dyed red from benibana (safflower), chirimen textiles dominate certain genres of ningyō and were used most extensively on the bibs of gosho-ningyō and in the decorated sleeves of many ishō-ningyō and Takeda-ningyō.

The final textile element that deserves special mention is birōdo (velvet). Like kinran and chirimen, velvet was originally an imported textile, but rather than originating from Chinese weaving traditions, birōdo came to Japan via Portuguese traders in the sixteenth century. The term itself is a corruption of the Spanish word for velvet, velludo. It was also known as betchin or velveteen. Birōdo was considered a decidedly luxurious fabric and in ningyō was used primarily as an accent element. It is found most consistently on Takeda-ningyō of the nineteenth century where it is used on the long eri (collars) of jackets, on sleeves, and on decorative panels running down the fronts of inner garments. Rather than being left plain, these birōdo elements frequently received additional embroidered treatments, or were embossed with metal appliqués. The iron mordant used to achieve the black color generally accelerated the deterioration of the material. As a consequence, birōdo fabrics often exhibit more wear than surrounding fabrics on the same piece.

Gofun

Like Buddhist sculptures, the bodies of ningyō were rarely left in a raw wood state but received various decorative treatments. The lustrous white found on the faces, hands, and bodies of many Japanese dolls is created from a material known as gofun. It is considered to be perhaps one of the most singularly defining characteristics of ningyō, one with no equivalent in any other culture. Gofun is a white composite paste made from crushed oyster shells and animal based glue (nikawa) mixed with water. When applied flat, it functions as a simple white pigment. When applied to hard surfaces and burnished, it creates a resilient, lacquer-like surface, very smooth, with a lustrous sheen. The glue element in the gofun mixture also gives it a plastic quality which allows it to be worked and molded to a small degree, creating raised lines and surfaces, and even minimal amounts of carving. Gofun has been used in Buddhist sculpture since the Kamakura period (1185-1333), where it was applied to the bodies of certain deities and used extensively on their carved garments. The makers of Noh masks have used gofun since the Muromachi period (1392-1573) to provide the lustrous white faces of many characters. Artists working on surfaces such as folding screens (byōbu), sliding door panels (fusuma), and architectural painting employed gofun as a matte pigment as well as using its plastic qualities to create raised design elements within the paintings in a technique called moriage. Lacquer artists valued these same properties and used gofun to create many of the raised design elements that graced a wide variety of utilitarian and decorative objects. Ningyō artists also utilized gofun extensively, burnishing it to a high sheen on the bodies, hands, and faces, giving these figures a heightened sense of beauty and mystery as well as greatly enhancing their appeal. In the construction of faces and hands on ningyō, gofun proved to be an excellent material to help create the finer detail elements of the face, including eyes, nose, and mouth. Rather than fully carving these aspects in the core wood, the artist could use the gofun much the way lacquer artists did to create the subtly raised lines demarcating the eyelids or lips, and building it up even higher to create the nose. Additional red and black pigments were added to further refine and delineate the feature.

Traces of white pigment have been found on certain haniwa figures dating from the sixth century, indicating the presence of native white pigments from at least the Kofun period. One of the earliest documented white pigments employed by Japanese artists and artisans was a lead-based pigment called impaku, introduced from China during the Nara period. Impaku was used extensively in all manner of applications, from architectural painting to sculpture, to devotional painting. However, the lead-based impaku tended to oxidize over time in Japans humid climate, limiting its appeal. The exact date of the introduction of gofun into Japan is unknown, but by the Kamakura period it began to replace impaku as a preferred source for white pigment in many media. Its plastic qualities gave gofun a wider range of applications than traditional white impaku. The "go" in gofun means "barbarian" and implies that the technique of manufacturing gofun was imported through China from points further west along the Silk Road.

Gofun is produced from oysters, particularly a variety known as itabogaki. The oysters are harvested and the shells left to dry in the sun in order to help leach out sodium and any remaining organic matter. Over time the hard surface of the shell softens and becomes chalky The upper and lower segments are then separated. Working with only the outside of the shell, the softened shell is then partially ground using a tool called a kai garuma (shell wheel), which further removes impurities. The remaining shells are then crushed and water is used to sluice and separate the elements. The ground shell fragments are then passed through a series of screens and left to dry in the sun. The result is a fine powder that when mixed with an animal-based paste forms an applicable white pigment. In doll and mask manufacture, a series of layers is applied, and each layer is burnished. The shell element in the gofun responds to the burnishing, yielding a lustrous quality not found in impaku. Repeated applications and burnishing result in a surface that is surprisingly durable, with a bright procelaneous sheen. Yet, it remains entirely water soluble and can be easily removed with a wet rag. During the Edo period, gofun production was centered in the Edokawachi section of Kyoto. Today, it is centered in Uji.

This brief discussion of materials is far from exhaustive. The interior structure of many ningyō forms reveals the use of bamboo dowels, metal pins, and cotton or silk wadding. Exterior elements include lacquered paper for armor, thin and thick metal bosses, and appliqués. Beginning in the eighteenth century, silk fiber or actual human hair was generally employed as well in the depiction of the various ningyō hairstyles. Silk fiber was also used to simulate fur-covered boots as well as the fur of animals. Core materials other than wood include ivory, clay, papier mâché, and a wood composite known as toso. Even plant materials such as rape seed (nanohana) were used to create hina-ningyō in certain communities. In the descriptions of the figures included in this volume, the appearance of these and other elements are noted to help create a greater understanding not only of the visual meaning and cultural symbolism represented by ningyō, but also the nuts and bolts that went into the creation of these marvelous works of art

Gosho-style ishō-ningyō: Jurōjin

Edo period, 19th century

Height 14 inches

Ayervais Collection

Standing gosho-ningyō holding infant

Edo period, 19th century

Height 7 inches

Rosen Collection