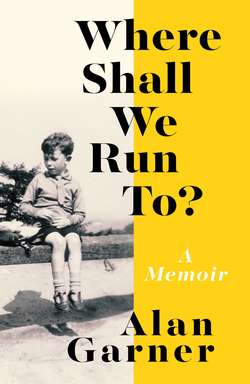

Читать книгу Where Shall We Run To?: A Memoir - Alan Garner, Alan Garner - Страница 11

Monsall

ОглавлениеI could read big letters but not little ones. I was being carried out of the house through the porch and I saw the bricks of the house on the corner of the road opposite and the iron plate painted white with the black letters STEVENS STREET. Then I was put down on a bed in a van with grey windows and tucked round in a blanket and a man in a hat with a shiny peak sat by me and held my hand and I went back to sleep.

The van was moving when I woke up and through the window I could see four black lines across the sky and they were dancing up and down and I asked the man what they were and he said they were the wires between telegraph poles. I watched them and went to sleep again.

There was a sharp pain at the bottom of my back, the sharpest worst pain I’d ever had and I woke up.

I was lying on my side on a stretcher in the open air next to a glass door. A woman in a blue dress and a white apron had her arms round me and another woman was holding a big needle and bending over the pain and telling me it would be all right. Then she helped to put me flat and I was carried up steps and through the glass door and along a corridor and the two women were holding my hands and talking to me and I was crying though the pain had stopped then I went to sleep again.

When I woke up I was in a bed. Someone spoke next to me but I couldn’t move my head. I looked sideways and could just see one of the women sitting on a chair near the bed and I could smell smells I’d smelt before and I knew I was in Monsall.

I’d been in Monsall when I was two and had diphtheria which was one of my big words. Another was ‘fumigated’ because that was what was done to the house after I’d gone to Monsall.

(© the author)

I remembered the woman was a nurse and she told me she was going to look after me but I mustn’t move or try to sit up and she gave me something to drink out of a small white teapot and put the spout between my lips and I could swallow but I couldn’t have moved if I’d wanted to. I had a headache all over. I couldn’t move at all.

I went to sleep.

I kept waking and hurting and sleeping. The nurse fed me from the teapot in the day and in the night. Her voice and face and the colour of her hair kept changing but she never left me. I could see sky through a big window on the right and there was a small round window on the left in the door of the room. Sometimes a man in a white coat came and felt my neck and turned my head and felt my arms and legs and talked to the nurse and to other nurses and men that came with him and he smiled but he didn’t speak to me. Then he left the room and the men and the nurses went except for the one that stayed.

It was daytime. I heard people talking outside the door but I couldn’t hear what they were saying. I saw head shapes in the round window. They were moving from side to side pushing each other.

I said, ‘Who’s that?’ and there was a noise and the nurse got up from her chair and went to the door and opened it enough for her to get through and I heard voices again and then they stopped and the nurse came back in and I started to cry because the noises had been too loud and hurt.

The nurse talked to me but I was still crying. She talked to me and held my hand. Then she held my wrist with her fingers and looked at her watch which was upside down on her chest. She put something under my tongue in my mouth and when she took it out and looked at it she said she was going to fetch something to make me feel better and went out of the room.

I stopped crying but I felt worried. I put my elbows down on the bed and pushed and sat up from the pillows and looked out of the big window.

The sky was blue with white fluffy clouds and I was looking down on a green lawn. A path went round the lawn and two people were walking away from me arm in arm. One was my mother wearing her best coat and hat and the other was my father in his soldier’s uniform.

The pain in my head and neck and back and arms and legs jabbed and jabbed and jabbed and jabbed and jabbed and I fell in the bed and was sick.

I got better later; enough to be moved into another room.

It was big and had children in it. I didn’t like them. They were noisy all the time, and those that were well enough to be out of bed and play were the worst. They ran around banging their toys; and they stopped me from reading my comics.

The very worst was called Arnold. His bed was next to mine on the right. He had yellow curly hair and big eyes, and he was always hitting the iron of his bedhead with a wooden hammer.

We had rice pudding to eat, and one day Arnold cacked himself and mixed it into his rice pudding with a spoon and ate it. I shouted for a nurse and told her what he’d done, but she laughed and gave him a bath.

My favourite comic was The Knock-Out. The best part in it was Stonehenge Kit the Ancient Brit, who was always fighting Whizzy the Wicked Wizard and his friends the Brit-bashers.

I couldn’t really read before I was in Monsall. I could read the words in the pictures because they were all big letters, but there was a lot more of the story below the pictures in both big and little letters, and I didn’t understand those.

I lay in bed and looked at the words. Some of the big letters were in the pictures and in the story below, and some of the little letters were the same as the big. I tried to work out what the strange ones were by putting them together. Names were the easiest. ‘KIT’ and ‘Kit’ must be the same. So ‘i’ was ‘I’, and ‘t’ was ‘T’. Then once I’d got that I saw ‘e’ was ‘E’, ‘n’ was ‘N’, ‘h’ was ‘H’, and ‘g’ was ‘G’ in ‘Stonehenge’. Then ‘b’ was ‘B’ in ‘Brit-basher’. And so, one at a time, I learnt the little letters; and after practising over and over, in one moment I saw I could read everything. I was that excited I had to stop and lie down flat in the bed. I was shaking and couldn’t hold the pages still. The sky was blue, with white fluffy clouds, and the sun shone on the barrage balloons.

Barrage balloons were tethered to the ground with cables for the cables to catch against the wings of German bombers in the Blitz and make them crash. The balloons were like fat silver sausages, and each had three fins to keep it steady.

Once, when I was at home, I heard a Spitfire engine and the sound of the machine guns. I went into Trafford Road and looked up and saw a barrage balloon had broken from its moorings and was drifting over the village and trailing its cable, and a Spitfire was trying to bring it down by shooting its fins and puncturing them so it fell gently without doing any damage or killing people. The pilot was circling round, being careful not to hit the body of the balloon, and I watched it sink until it disappeared over the Woodhill and the Edge.

As soon as I could read properly, Arnold didn’t bother me much. Because I was reading, I didn’t hear him. And when I was well enough to get out of bed my mother and father were allowed to come and visit me.

They could come for fifteen minutes, but they had to stand outside and shout through the window, and the window had to be shut tight.

I told them about Arnold and how he’d cacked himself and how I could read now, and kept asking when I was coming home. And they laughed and my father said keep calm and carry on, which everybody used to say. And then the fifteen minutes were up and they had to go and it was somebody else’s turn for fifteen minutes. We kissed through the glass and the glass was cold and we waved and I cried and they went home. And I went back to bed and read my comics.