Читать книгу Where Shall We Run To?: A Memoir - Alan Garner, Alan Garner - Страница 9

The Nettling of Harold

ОглавлениеWe were my cousins Betty and Geoffrey, me; Harold, his older brother Gordon, and baby Arthur; Ruth and Mary, sisters; and Iris. Betty and Iris were Big Girls, though Iris couldn’t read. Arthur was there because he was in nappies and Harold had to look after him all the time. We were the Belmont Gang. I lived half a mile away, but my grandma lived at number 11, so I was let in, though I was a strug because I didn’t come from Belmont. A strug was the word my uncle Syd and Harold’s father used for a stray pigeon.

My grandma was old, and had wrinkly brown skin and silver hair and could skip better than the girls. She’d moved from Congleton to live in the village to be near her family because a war was starting, and number 11 was empty because the man living there had hanged himself in the lavatory.

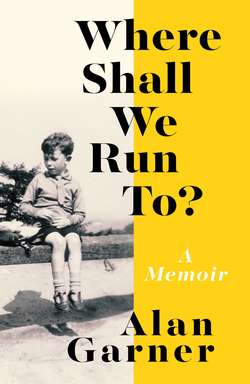

The Belmont Gang, 1939. Back row, left to right: Betty, me, Gordon, Iris. Front row: Mary, Ruth, Geoffrey, Harold with baby Arthur (© the author)

Belmont had been built as four blocks of three houses in Potts’s brickyard field. Each house was two up and two down, with a kitchen, and a garden at the front and a walled yard at the back. Later they had a lavatory added on in the yard. The cistern was in the kitchen to stop the pipe from freezing, and the chain went over a wheel and through the wall. We used to wait until people were sitting down and then pulled the chain to make them shout.

Next to my grandma lived Mr and Mrs Kirkham. They were old, too, but they kept themselves to themselves.

One day, the police had come from Macclesfield and told Mr and Mrs Kirkham they must move out because the house was going to be searched. They went to stay at number 11. This was before my grandma lived there.

The police lifted up the bedroom floorboards and the stone flags downstairs, and took out the built-in cupboards and made holes in the ceilings and tapped the walls and broke through the plaster and the bricks where they heard hollow sounds. And in each place they found money and jewellery and gold and silver. Burglars had lived in the house earlier and had hidden their loot there.

The police put everything back properly and tidied and redecorated the house, but my grandma said Mr and Mrs Kirkham were so upset they were never really happy again.

The allotments for the houses were separate strips, side by side, and my uncle Syd and Harold’s father had their pigeon cotes there. We played on the patch of sand where the privies had been before Belmont was modernized.

When the war came, a brick air-raid shelter with a flat concrete roof was built, and it was dark, and the voices of grown-ups swore at us from inside when we tried to look.

There was an oak tree next to the shelter. We climbed onto the roof by putting our backs against the wall and walking up the trunk of the tree. The roof was our aerodrome, and we used to run round it with our arms out, preparing for take-off, and then have dogfights. Harold was a Messerschmitt 109, or a Focke-Wulf 190, because people said his great-grandfather had been a Gypsy. I was a Spitfire, because I could make the noise of a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. This meant Harold was always shot down and had to crash by jumping off the roof. He liked that. But I was too scared, and landed by hanging from the concrete and dropping into the grass.

I kept a hedgehog in a hutch on my grandma’s allotment, and Harold and I gathered slugs to feed it. We picked the big black ones, and sometimes we found orange and grey. We popped the slugs with splinters of glass to make them easier for the hedgehog to eat, and we watched the innards, trying to work out which bits were which. We were both interested in Nature.

We were interested in everything.

I saved up by taking empties back to Mayoh’s off-licence and collecting the tuppence deposit, and I once got into trouble with my mother for carrying the beer bottles in a basket without covering them with paper, because people could see. I bought myself Woodpecker cider with the deposit money, and spent some on carbide which Dobbin Brooks sold at his bike shop for making the flame of acetylene lamps.

Harold and I went fishing at the Electric Light Works, further along Heyes Lane, in a big concrete water tank. A woman had drowned herself there, but we weren’t bothered in the daytime.

We put stones in an empty cider bottle, filled the bottle with water to just below the neck, and dropped lumps of carbide in. The lumps started to fizz as soon as they were wet, and we screwed the top on fast and tight and threw the bottle into the tank and watched it sink. Then we waited, excited; and the longer we waited the more excited we got; but we didn’t make any noise.

We were waiting for the explosion to thud, and the dome of water and bubbles the same as the depth charges we saw in the newsreels at The Regal. Then the fish came up, stunned or dead, and we pulled them in with branches. They were sticklebacks. We couldn’t eat them, because they were small and had spines, and I couldn’t get the deposit back on the bottle; but that didn’t matter.

The bottles had another scientific use.

We took them into the allotments where the long grass grew under the fruit bushes. We sat and turned the screw tops back and to, which gave a sound like the mating call of grasshoppers rubbing their legs on their wings. We were soon covered with grasshoppers. They were on our clothes and in our hair, and they tickled our necks and faces, and tried to go up our noses and into our ears.

The allotments belonged to us. Although each house had its plot, the plots joined, and we moved between, following the fruit. We made our dens in the grass below the roof of leaves, which gave a light not like outside; and we golloped raspberries and blackcurrants and we talked.

We talked about why the sky was blue, why blood was red. Was it true if you put a hair from a white horse on your hand when Twiggy caned you the cane would break? Harold said stones in fields grew, because they came up every time a field was ploughed; but I said they didn’t. My grandma had been a teacher, and she’d given me her Arthur Mee’s The Children’s Encyclopaedia of 1910, which taught in a different way from school. It asked and answered the questions teachers didn’t, and had all sorts in it, but nothing about stones growing.

Why did stars twinkle? What was a rainbow? Why did lightning make thunder? How far off was the moon? How long would it take to get there in a steam train travelling at sixty miles an hour? And we asked our own questions. Where would they get the coal for the train from on the way to the moon? Why did the wind make leaves turn over before rain? Why did bubbles come on puddles just before the end of a downpour? Why, in the films at The Regal, did the spokes of car and wagon wheels go backwards? Did God watch us pee?

Why did nettles sting?

It mattered to me, a mardy-arse. I always made sure I knew where the dock leaves grew to stop the hurt. And it mattered most of all every year on Oak Apple Day, the twenty-ninth of May. Then, the boys used to run around holding nettles and stinging anybody not wearing an oak apple or an oak leaf. I got both ready the night before, so I couldn’t be caught on the way to school.

Next to the air-raid shelter there was a great clump of nettles, Roman nettles, with purple stems. They were the worst.

I was standing by the clump with Harold, and I thought of the pain of one nettle. Here there were ever so many, hundreds. How much pain would that be? Would rubbing dock leaves on be enough to cure it? If one nettle made me cry, what would all these do? It was a big question; a scientific question. I must find the answer.

I moved behind Harold, put both hands between his shoulders, and pushed him in.

I’d not heard a boy scream before. It went on. It didn’t stop. It wasn’t Harold. I ran. I ran all the way home, up the stairs, fell on my bed, and yelled and yelled, still hearing the scream in my head, and cried and cried; but I hadn’t got any dock leaves.

The next day, Harold called me a daft beggar and a mucky pup.

It was the time of the Liverpool and Manchester Blitz. My father joined the army to guard us against Hitler at Rhyl, and my mother and I went to Belmont every night to sleep with my grandma.

When the air-raid siren alert sounded we took cover in the gloryhole under the stairs. But that was damp and smelt of feet and old shoes, and after a while we stayed in bed. The brick and concrete shelter was never used.

I listened to the sound of the Dornier 17s, the Junkers 88s and the Heinkel 111s passing. The Heinkel engines made a low, beating noise. Then the Ack-Ack guns in Baguley’s fields opened up and shook the furniture.

When the all-clear sounded, the Gang went out into Heyes Lane with torches to look for shrapnel. The glass in the torches was covered with black paper and had only a thin cross cut to show light; and we were careful not to point upwards, in case Jerry saw us.

Shrapnel was the bits of exploded shells meant to hit the bombers, and it had to be handled carefully because it was jagged and sharp. We wrapped the pieces in our handkerchiefs and swapped them in school at playtime next day. Hot-found ones were worth twice as much as cold-found; I don’t know how we told the difference.

Harold was lucky one night and found a German incendiary bomb that hadn’t exploded properly. It was in the gutter near Nancy Ford’s shop, and it was like a bicycle pump, and a sticky white paste with a nasty smell was coming out of the cracks in the metal. We were all looking at it in the playground next day, but we made so much noise Miss Fletcher heard and came out and took it off us. We never did find another, and Harold was vexed for a long time after.

The air-raid siren in the village was the best in Cheshire, Harold said. It was always the first to sound the alert and the first to sound the all-clear. The rest followed, one after the other, at different times.

I told him it was because of the speed of sound, same as thunder after lightning. The sirens sounded all at once, I said, but we heard them later because they were further away. I’d shown him in The Children’s Encyclopaedia, and how you could tell the distance by counting the seconds between the flash and the thunder. A second was as long as it took to say ‘my-pet-monkey’, and sound travelled a mile in five seconds. But Harold wouldn’t have it. He agreed about lightning and thunder because he’d seen it in the encyclopaedia; but there was nothing about air-raid sirens; so we still had the best.

When the war came we sang in the playground:

‘We’re going to hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line!

Have you any dirty washing, Mother dear?’

It was one of the songs soldiers sang, and we heard it on the wireless and in newsreels at The Regal. In school, with Miss Turner, we sang ‘Waltzing Matilda’ and ‘The Raggle-Taggle Gypsies’ and ‘The Ash Grove’. ‘Waltzing Matilda’ was a song from Australia about a man who stole a sheep and was caught and drowned himself and turned into a ghost. It had good words in it; words like ‘swagman’, ‘billabong’, ‘coolibah’, ‘jumbuck’, and ‘tucker’. ‘The Raggle-Taggle Gypsies’ was about a rich young lady who fell in love with a Gypsy and ran away with him and slept in the cold cold fields, and I wondered if she was related to Harold, or was one of the Gypsies that came and sat in our garden sometimes, but I never saw any that looked like her. ‘The Ash Grove’ was sad and made me want to cry.

One year, headmaster Twiggy had the whole school do a Carol Concert at Christmas to please Canon Gravell, with Miss Bratt playing the piano and him conducting.

Nobody liked Twiggy. He made us scared of him on purpose. And in the practices he never said we were any good but always how bad we were and how we didn’t sing the words clearly. But that was because some of us weren’t singing the real words at all. We were singing what we sang in the playground.

It was Harold’s idea.

The knacky bit was to have only the Gang in on it, which was eight of us out of nearly three hundred in the school. If Twiggy did hear what we were singing he wouldn’t be able to tell who it was.

So we sang:

‘While shepherds washed their socks by night

All sat around the tub,

A bar of Sunlight soap fell down

And they began to scrub.’

Then we sang:

‘Hark! The jelly babies sing,

Beecham’s Pills are just the thing.

They are gentle, meek and mild,

Two for a man and one for a child.

If you want to go to Heaven,

You must take a dose of seven.

If you want to go to Hell,

Take the blinking box as well!

Hark! The jelly babies sing

Beecham’s Pills are just the thing.’

Then there was another.

‘Good King Wences last looked out

Of the bedroom winder.

Silly bugger he fell out

On a red hot cinder.

Brightly shone his arse that night,

Though the frost was cruel,

When a poor man came in sight

Gathering winter fue-oh-Hell!’

And the best was to end with.

‘O come, all ye faithful!

Butter from the Maypole,

Cheese from the Co-op

And milk from the cow.

Bread from George Cragg bakers,

Beer from Billy Mayoh.

O come let’s kick the door in!

O come let’s kick the door in!

O come let’s kick the door in!

Twiggy’s a turd!’

At the finish, Canon Gravell thanked Twiggy, not us. Then we broke up for Christmas. And the Gang laughed.

Soon after the war ended, though, Mr Ellis, our class teacher, told my parents I should go into Manchester and take a test. None of us knew what he was talking about. My class was being tested all the time, practising for the Eleven Plus exam. But my mother said because Mr Ellis was Cornish he had the Second Sight; and I liked him. A lot didn’t. He let me read to myself in class while the others were reading aloud. He taught me to play chess and he taught me special punctuation. I liked semi-colons. He was strict, but not bad-tempered like Twiggy.

So I went to Manchester and took the test, along with two thousand other boys, in a room as big as The Regal.

A letter came in the post some time after, and my mother was waiting for me at the end of School Lane when lessons were over. She told me I’d won a scholarship.

That evening, the Gang were playing round the sand patch. It was Ticky-on-Wood. Harold’s mother came out of the house. Her face was different. ‘Well, Alan,’ she said, ‘you won’t want to speak to us any more.’

I didn’t understand. I felt something go and not come back.