Читать книгу Everything Happens as It Does - Albena Stambolova - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4.

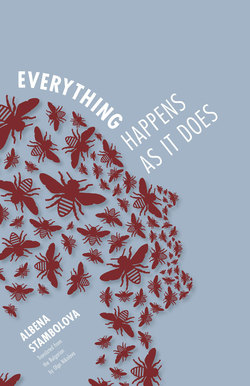

Bees and Their Friends

Boris cohabited with bees; bees cohabited with him. The very first time his father took him to the beehive not too far from the house, the bees and Boris immediately took to each other. He was interested in the way his father pulled the honeycomb frames and pushed them back like drawers. They made the same sound. It all seemed like a game to his childish eyes.

Later his father would say that the bees did not gather around him, but swarmed around Boris. His father’s head was covered with a net, propped from below by a wide-brimmed hat. The shape of a planet. But Boris would learn this only later, in school. That there were celestial bodies, spheres, some of them with rings. Saturn. His father’s head at the beehive was like Saturn. Boris liked Saturn very much.

Later, when Maria read ancient Greek myths to him, he learned that Saturn was the father of Jupiter. Or rather, that Chronos was the father of Zeus. Saturn and Jupiter were their Latin names.

Maria had become his wife by then. But at the beehive he had no idea she even existed.

After that first time, Boris regularly went with his father to see the bees. He did not like the taste of honey. Perhaps that was why the bees liked him. He ate honey sometimes, because he had to comply with his mother’s wishes, but he never enjoyed it. He knew from the very beginning that honey belonged to the bees, and his father rattling the drawers now seemed silly.

When he found a wild beehive for the first time, he saw how imperfect the man-made beehives were, with their little toy roofs. Doll houses in which the bees were forced to do what they naturally did anyway. Such things, and others, would cross his mind.

At some point he learned that there were queen bees, drones, and brood chambers, and this filled him with admiration. The worker-bees worked; they did their tasks without thinking. Boris decided that human beings were imperfect in comparison, because they would always think while doing things. And they would tire—whereas bees never grew tired. They simply reacted to changes in temperature. They stopped being bees below such-and-such degrees.

He gathered honey, filling jars with amber. Other people in the village also had beehives, but Boris seemed to have a special gift; he was so good at it that everyone relished his honey.

He never put on a beekeeper’s veil. Not a single bee ever bothered or stung him. Boris found bees to be perfect and tried to learn everything there was to learn about them. Then he became the bees’ man. And they became Boris’s bees.

Year in, year out, the same thing would happen. Boris would lie down in the tall, soft grass between the beehives. At first he would hear them moving along their flight paths, then a wave of information signals that he could clearly sense would traverse the air. The bees would start hovering above him, and he knew that they were trying to decide which ones should descend on him. They would begin to land on him, covering first the bare skin, his hands and face, and afterward his entire body. They would stay there until he stirred to get up. Then they would lift off at once like a cloud of sound and he would walk away. He would eventually leave them behind and they would again busy themselves about their bee work.

No one knew that Boris and the bees had a special relationship. Or perhaps no one wished to know. The bees, just as the glasses did later, provided enough explanation for the boy’s absentminded wandering, his reticence and his lack of interest in the food on his plate.