Читать книгу Homunculus - Aleksandar Prokopiev - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

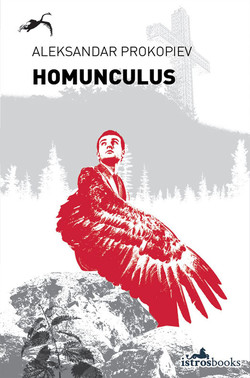

ОглавлениеForeword

Aleksandar Prokopiev’s fiction resembles very little that will be familiar to English readers. It has the fantastical darkness of folk material but, like the novels of Angela Carter, it inflects this matter with high cultural allusions. Tom Thumb rubs shoulders with the humanist philosopher Pico della Mirandola; an icon painter with a talking frog. At the same time, and rather more like the Latin American novelist Roberto Bolaño, Prokopiev creates a fictional world that doesn’t differentiate between the invented, the factual and the autobiographical. Much of ‘Once Upon a Prokopiev’, the last story in this volume, for example, is taken from the writer’s own life.

This mixture is exciting and kaleidoscopic. It makes the stories in Homunculus feel hyper-animated, if not hyperbolic. It also has a serious purpose, which is to destabilize the reader, who will no longer be able to keep “the real world” and “fiction” safely apart. In other words, “true” fiction reminds us that our inner lives are composed not only of daydream but also of memory, and – perhaps more sinisterly – not only of truth but of invention. Prokopiev’s first collection of short stories, published in 1983, appeared to acknowledge this with its challenging title, The Young Master of the Game. And he is indeed a game-playing writer, who is not merely playful but uses codes and sophisticated rules to create narratives layered with meanings.

Some of this playfulness comes directly from folk material, whose dream logic and incompletion literary writers have long found evocative but which this author deploys with real knowledge. Prokopiev’s doctoral work, undertaken at the University of Belgrade and the Sorbonne, conducted original research into the folk stories of what was then southern Yugoslavia. An early collection of essays is titled Fairy-story On the Road (1996), and he is now the Professor of Comparative Literature at the National University of Ss Cyril and Methodius.

Nevertheless, Prokopiev would describe himself as a postmodernist, an orientation that other titles among his thirteen collections of fiction and essays suggest. These include …or… (1986), Anti-instructions for Personal Use (2000) and Postmodern Babylon (2000). But there’s nothing po-faced or overly systemic about this engagement with philosophy. Prokopiev is always fun to read. In fact, in his native Macedonia, this former rock star – he was a founder member of the New Wave band Idoli, notorious for their ambiguous anthem ‘I seldom see you with girls’ – is something of a media don, as well as a highly influential cultural critic. In that southernmost state of the old “Southern Slavs” – yugo means south – the rural and the urban, tradition and the contemporary world, are closer neighbours than they are in many northern European countries. An intellectual like Prokopiev, who was born in the capital, Skopje, in 1953, isn’t divorced from the world of Roma music, peasant farming and rural superstition that still surrounds and intermingles with the more globalized culture of university or city bar.

For much of the year, the people of Skopje and its hinterland lead an outdoor, public life of terraces and cafes. This is also a post-communist culture, and those who grew up here before 1989 – as Prokopiev did – became accustomed to relatively little personal space. This gives the Republic’s culture, like that of its Balkan neighbours an oral vibrancy, which Prokopiev brilliantly and continually captures. One small example: when the swan-girl’s breasts, in ‘The Man with One Wing’, start out ‘orange-shaped’ but soon grow ‘grapefruit-shaped’, our narrator is making a little play on the mounting hyperbole of traditional story-telling.

For Prokopiev is a storyteller, not a textual mechanic. His contes are full of emotion, and of archetype. They are also full of darkness, as befits a country still sitting on the fault line that produced the wars, which pulled the former Yugoslavia apart at the end of the twentieth century. The war in Macedonia was the last to be formally concluded; nevertheless, this small country of just over two million inhabitants did not allow itself to be torn apart along ethnic or religious grounds. It remains a mixed Orthodox Christian and Muslim country, whose official languages are Macedonian – a Slav language closely related to Bulgarian which uses the Cyrillic alphabet

– and, in municipalities with a local majority population, Albanian, an Indo-European language which has no relatives but uses the Roman alphabet.

There is tremendous intimacy in writing for a language-community of roughly one and a half million people. Aleksandar Prokopiev is by turns mischievous – in ‘The Dance of the Coloured Handkerchiefs’, a story to make boys and girls of all ages smile, the protagonist-handkerchief longs for snot – admonitory. ‘Marko’s Little Sister’ reads like a cross between ‘The Boy who Cried Wolf’ and an Awful Warning against self-harm) and is challenging: “The smell of the forest, the smell of gunpowder, and the calm certainty of death. How exciting it is!” ends ‘The Huntsman’. But, however much the intimate raconteur appeals to our inner child, much more is also going on in such fictions. The shadows these bedside stories cast are genuine monsters, as in this volume’s parables about morality, (‘Neverland’, ‘The Huntsman’), history (‘Human, All Too Human’, ‘The Haji, The Shoemaker and the Fool’), and identity (‘A Christmas Tale’, ‘Homunculus’).

That Prokopiev manages to combine the great and the small, coining archetypes while winking at a local joke over a glass of Skopsko beer, is both astonishing and delightful. Now perhaps the ‘middle-aged master of the game’, he is unique in dedicating his writing life almost completely to the short story form. (As well as his essays, a novel, Peeper, appeared in 2007 – and was the national entry for the Balkanika Prize.) The results can be seen in his influence on many middle-generation Balkan writers, and in the numerous foreign editions, and the awards, his work has received: culminating in the international Balkanika Prize 2010, awarded to Homunculus.

Often surreal, sometimes inexplicable, Aleksandar Prokopiev is one of the ‘must-reads’. He is a teasing, telling interlocutor who likes to play the naïve; the brilliant Fool who is a figure as recognizable from our traditions as from his own. These shape-shifting stories remain adamantly and radically open for us to interpret. They challenge us to accept, even to embrace, our own confusion: implying, perhaps, that life itself is as confusing as any fable. To read them is to glimpse the wildness at the heart of Europe.

Fiona Sampson

Coleshill 24/2/15