Читать книгу Homunculus - Aleksandar Prokopiev - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThis fairy tale is to be told during coffee breaks from Monday to Wednesday

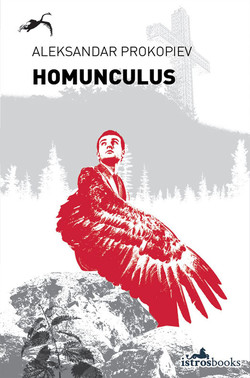

The Man with One Wing

Once there was a man who had one wing. Unlike an angel’s wings, which grow out of its back, this man’s wing was in the place of his right arm, and unlike a bird’s it had a flexible elbow, which he rested on as he sat on a large rock and stared away into the distance as if looking out to sea: but there was no sea, only a hillside clearing with a few scattered trees.

For the man with one wing, that summer was one of the most depressing of his life. He was haunted by a sense of emptiness and futility, a feeling heightened on those July afternoons by the stale, sour smell rising from the hot city, that sticky mass of cars and people constantly creeping like a foul treacle and defiling even the narrowest alleyways. The man with one wing sat on that rock halfway up Mount Vodno and looked into the sky, following a cloud that was forever changing shape, like every restless puff of vapour, and he thought: Just look at that cloud. It can do whatever it wants, while I...

At that very moment, a bird came flying up. It was an eagle, as large as in fairy tales, and it obscured the sun and the restless cloud. The huge bird descended to within a yard of the man with one wing, hovering in the air, and looked straight at him.

‘What do you want of me?’ asked the man with one wing in the shadow of the eagle.

It replied with a question: ‘Why are you still on the ground?’

‘Can’t you see I only have one wing? What can I do if I’m crippled like this? Without a right hand, I can’t even wank. But why have you come? Did I call you?’

‘I’ve come to tell you something very important. You may not want to hear it, but that can’t be helped: I am your cousin.’

‘What?!’

‘All right, not a first cousin. Perhaps four or five times removed. But we are related. Our common relation, the Grey Eagle – that is your father, and a distant uncle of mine – once accidentally brushed your mother with his wing and she fell pregnant.’

‘Even if that’s true, what does it have to do with me now?’

‘You are the one in whom bird and man are united. Moreover, you are the only son of the Grey Eagle, and he is the king of the eagles. He is dying and asks me to bring you to him. He wants to see you.’

And so the man with one wing climbed onto the eagle’s back and the huge bird bore him away. As fast as the wind it flew, swiftly passing mountains, lakes and rivers, and soon they reached a lofty mountain peak covered in snow. Here there was a large eyrie, with a throne in the middle and a white fireplace, whose flames burned with a strange light, white and pure. Despite the snow and ice all around, it was pleasantly warm inside the eyrie. This was the home of the Grey Eagle.

The great bird sat, or rather lay slumped, atop the throne. Not even the fire could allay the fever that raged in his once mighty, kingly frame.

‘My son,’ he spoke to the man with one wing, ‘tonight I leave for the land of our ancestors. I do not wish to go, but I have no choice – my time has come. I have never troubled you before, but since my last hour is drawing near I have resolved to share the secret that I am your father.’

‘I know that already. It seems rather obvious, doesn’t it?’

‘But there’s something more. With my death, the throne of the eagles will become vacant. It awaits you, and it is for you to choose if you will ascend it. May the birds in your right half and the men in your left decide your course.’

‘I don’t know what to say. You’ve really caught me unprepared.’

‘You must decide. I am growing weaker, ever weaker, and I must know your answer. Will you stay here or go back to live among men? And one other thing: how is your mother?’

‘She is well, for her age.’

‘How old is she exactly?’

‘Seventy-five.’

‘That old already? It seems like just yesterday that I brushed her with my wing. You should have seen me in my prime.’

The man with one wing failed to notice that his father had tried to soften the situation with humour. He still didn’t understand what was going on and stood there gawping, his mind a muddle. The Grey Eagle lifted his heavy head with visible effort and spoke to him for the last time:

‘Tell me, my son, will you be my heir? Will you become the king of all birds? I’m glad I sent for you, my son...’

‘I... I...,’ the man with one wing stuttered, but the Grey Eagle could no longer hear him. He had passed out into the narrow way separating the two worlds, where the sounds of this world become ever fainter and are soon gone.

And so, without really wanting to, the man with one wing became king of the eagles, to the acclaim of the entire aquiline assembly.

‘How can I possibly rule when I can’t even fly, let alone soar up to the heights?’ the man wondered, sitting on the throne of stone that now struck him as being very similar to the rock halfway up Mount Vodno, which he had climbed to escape the city before this remarkable episode with his father, the Grey Eagle. But since he was now king, which meant that all the eagles were now at his service, he ordered for a large, light and powerful wing to be made for him as soon as possible and that it be affixed, gently but firmly, to the left side of his back. He noticed that giving the order came easily to him, and no sooner had he spoken than his wish was fulfilled!

He was no longer a man with one wing but a king with two wings. Or rather, two wings and one arm. His left arm, now solitary, white and oddly beautiful in its helplessness, could be used for noble deeds such as bearing the sceptre or leafing through a travel book illustrated with etchings. The places on the man’s back where his wings were, the natural one and the new artificial one, pulsated and tingled most pleasantly.

‘Now I can take to the sky!’ he cried and launched into flight.

Yes, it was as if all the energy had returned to his body, and as he breathed in the air of the heights – so intoxicating, so liberating – he felt he was bending the skies to his will and seizing life in a completely different way to before. The waters of the mountain rivers rushed, babbling through forested dells far below him; houses, even large buildings looked like little models from a children’s game. He, the eagle king, felt proud and majestic, and he laughed loud and long above the clouds: ‘Ha, ha, ha! Ha, ha, ha!’

He flew to see his mother, who was not astonished to see him as an eagle. In fact, she seemed to be relieved.

‘You don’t have to explain anything. I understand,’ she heartened him.

His mother, who was not seventy-five but actually eighty, could finally be proud of her son. He wore his wings like a royal cloak draped over his left arm.

‘Mother, so far I have caused you nothing but trouble with my restlessness and complexes, but now I am strong and self-confident. Tell me, is there a wish I can fulfil to gratify you for once?’

His mother was quiet and thought for a minute or more, and then she spoke in a rush, like a river suddenly released: ‘My son, it’s true you were awkward and idle for many years and caused me much pain and embarrassment. My friends gossiped about you time and again, and afterwards I couldn’t sleep for nights on end. I’m not saying it was your fault – perhaps we had to go through it all because fate decided it should be that way. But we cannot change the past. And when I see you now, so tall and handsome, I could cry... with happiness...’

‘Don’t cry, mother!’

‘I have become old and sentimental, but it will pass. Let me think of a wish you could fulfil for me.’

‘Tell me, mother, tell me!’

‘Ah, I know. Last night, or the night before, I dreamed of a girl. She was beautiful and she lived by the shore of a mountain lake, so high that in winter the moss was covered in six inches of snow.’

‘It suits me that it should be high up. Since I’ve had two wings I’ve become very fond of heights.’

‘Yes, I believe you. But there was something else in the dream, too, some little problem. Just let me just try and remember what it was.’

‘Don’t strain, mother. Whatever it is, I shall overcome the problem.’

Later, back on his throne, the former man with one wing and current king of the eagles steeled his resolve: A man, even one with two wings, must follow the path fate has chosen for him without turning aside. He must walk it to its end and then, if he can, he must understand his role in the wheel of life.

He ordered all his winged subjects to begin searching near and far for a girl of indisputable beauty living by the shore of a high mountain lake. All the eagles immediately set off to the four corners of the world, and our hero, not wishing to sit alone and bored in his eyrie, joined in the search himself.

He flew long and hard until, after a whole week, one day at high noon he saw a dark-blue lake at the peak of a tall mountain. Three swans were bathing in its clean, clear waters, and three dresses lay on the shore. Why are there swans this high up? And what are these dresses doing here? He was right to wonder. He hid behind a snow-covered pine tree and peered out: one of the swans emerged from the water, shook its feathers and began to change into a beautiful girl. Shivering with cold, she donned her golden dress and ran barefoot across the snow, down to a stone cottage. The second swan came out and the same process was repeated. It too turned into a beautiful girl who, predictably, put on her silver dress and ran after her sister.

But before the third swan could leave the lake, the eagle king sneaked out from behind the pine tree and snatched the white dress. Terrified, the swan paddled back over the water and spoke to him in the gentle voice of a girl: ‘Please give me my dress back.’

‘All right, come up onto the shore and take it. I’ll hang it on this pine branch and go round behind the tree.’

The swan-girl thought to herself: I’ll grab my dress and start running.

But the eagle king thought: As soon as she comes nearer she’s mine!

The swan-girl ran up onto the shore, making for the branch where her white dress was hanging. She moved fast, but the eagle king was faster. He leapt in front of her and seized her in his eagle’s embrace. At that instant, her body began to change and shed its feathers, first revealing her long, white, fragrant neck, and soon a shock of blonde curls danced in front of him and tickled his nose. He was no longer touching the body of a swan but that of a young woman, whose skin breathed and shone much more suggestively than the feathers. He took half a step backwards, less in shyness than from the desire to feast his eyes on her. As her body was gradually exposed to him, disclosing its beauty inch by inch, his excitement grew and redoubled; he relished the sight but was aware that there were enticing secret chambers and shady gardens yet to be discovered. He was still holding her in a half-embrace. Was it just his imagination that her velvety eyes, darker than her hair, grew large and moist when his old right wing brushed against the hard nipple of her now fully human, orange-shaped breast? As he hugged her nymphean body, his wing feathers reacted with unseen sensitivity and puffed up like the plumage of a strutting rooster.

He so revelled in the view that he scarcely heard her softly spoken words: ‘Would you mind passing me my dress?’

Only then did he realize that she was wet and shivering with cold. He handed her the dress, and as she raised her arms to pull it over her head she revealed all her feminine beauty: her slender waist, wide white hips and bushy mound. It took him a few moments to come to his senses and understand what she was saying, because as soon as she had put on her dress she began telling her story. It seemed strangely familiar (had he heard it from his mother or someone even older?).

Eliza, for that was the name of this gentle yet voluptuous creature, and her sisters, all of them of noble birth, had become entangled in the dark magic of their stepmother. She was in fact a witch, who had enchanted their frivolous father, and then one afternoon when he was away she cast a bewitched shirt over each of the girls and turned them into swans. So no one would see their misery, they flew far away to a lake at the peak of a mountain. And so they had been living here as swans for seven years. They could only return to human form at noon, and never for more than one hour, after which they turned back into swans.

‘And I so yearned for a second wing,’ our hero let slip, but Eliza was carried away in relating her own sad story and didn’t quite catch his comment.

‘Yes, I also yearn to be what I was... there is a way we can be saved, but it would be such a long, hard road for our redeemer,’ she sighed.

‘Tell me how! Tell me right away!’

‘I don’t know if it’s proper...’

‘Proper or not, I want only to make you happy, you and myself.’

‘All right: you must not smile or speak a word to anyone for a whole year.’

‘That will be far from easy, to be sure, but if needs be I will neither smile nor speak a single word. My eagles might not understand at first, but I’ll find a way. There’s mime, after all.’

‘You’re making a big sacrifice for me. But that’s not all. There’s another very difficult task.’

‘I will face the challenge, I can’t give up now. But why are you being so self-conscious? There’s no need, although it makes me even fonder of you.’

‘Then I’ll tell you: in the year ahead, as well as not speaking or smiling, you must knit three shirts. For me and my sisters.’

‘Three shirts? Now that really amazes me. I’ve never done any women’s work in my life. Men don’t knit, you know.’

‘There’s something more I have to tell you. The shirts must be made of stinging nettles. Now you see all the trials and tribulations you have to undergo to save me from the spell. Me and my sisters.’

‘Eliza, your solidarity is moving. I must admit I don’t understand these sacrifices, maybe because I’ve been such a loner till now.’

‘It’s a tradition of my people. According to our legends, the world was knitted into creation. Divine knitting needles patiently created all these mountains with their holy tarns and lakes and snow-capped peaks, all these dark-green forests, as well as all the cabbages, blueberries and potatoes, the cows, wolves and eagles.’

‘Eagles?’

‘Yes, all the beasts and birds are made of divine yarn.’

‘And people too?’

‘All of us are connected by the threads of the divine knitting-women. The whole universe is made of those strong, invisible threads whose task is to preserve its equilibrium: the balance between the external and the internal, between the skies and the deep, between male and female. The women of our people therefore keep our clothes white by washing them in the clean, cold mountain lakes and streams. But –,’ Eliza sighed, ‘there are also witches, like my stepmother, who attack and unpick the fabric of the universe. That’s why she tangled the threads of the divine yarn and turned us into swans.’

‘Then it looks as if some wicked witch has been at work on me, too.’

Eliza’s cheeks, already aglow from the excitement of storytelling, now turned crimson: ‘But your appearance... how can I put it...the way you look really suits you. It makes you strong and manly. Oh, my dear, will you be able to make this sacrifice for my sake? For our future happiness and all the pleasures that await us? From the moment you say “yes” you’ll have to hold your silence for a whole year, you won’t be allowed to smile, and you’ll have to knit those nettle shirts.’ She straightened her grapefruit-shaped breasts, which seemed to burgeon even more under her wet dress. ‘I so much want to believe you’ll succeed. After all... sorry for having to mention it... but you do only have one arm.’

At that, his weak left arm clasped her to him: ‘At the risk of sounding blunt, Liza, why can’t we... while we’re mulling over all this... why can’t you and I get to know each other a bit better now, you know.

‘There will be time for everything, my love. If our plan works, there will be joys you have never dreamed of. But now you must say “yes” and refrain from words and smiles for a whole year – a year of knitting, knitting and more knitting until you see us flying back to you and the finished shirts.’

A ‘yes’ slipped from his mouth, and then there was no going back.

And so the eagle king, with a heavy heart, parted with Eliza and flew to see his mother in silence. She noticed straight away that something was wrong.

‘You’ve gone very quiet, my son. Much has happened to you of late. Here, show me what troubles you – draw it in the air with your wings, or with your hand, or with your eyes. I’m your mother, I’ll understand.’

So he started to wave, wheel around, hop up and down, and open his eyes wide and squeeze them shut again. It would have seemed most peculiar to anyone else, but not to his mother, who gradually, by a logic known only to her, began to understand what he was trying to say.

‘It won’t be easy at all. I remember being told something like that in a dream, but you were impatient and didn’t listen to me. Still, I’ll do all I can to help. It will be hard going until you learn to knit properly, especially at the beginning, but as soon as you’ve knitted your first stitches it will become easier and you’ll be surprised how quickly it goes. For you, my son, things are a bit more complicated with just your one arm, and even your father, for all his experience, was not particularly good at using his wings. But let’s not complain. Sit down now and listen. In one of your hands – the left one in your case – you take an old-fashioned knitting needle with a hook at the end. Nod to me if you understand. Good. And then you’ll use your right wing like this to hold the thread and wrap it around. Yes, just like that. First make one loop, slowly, and now pull the thread with the hand holding the needle and make a braid, a plait. I know it’s hard, my son, but if you can make that braid you know all there is to know. Come on, one more time. Don’t get frustrated. In time, you’ll find it so easy you’ll be able to do it with a nail. You pick up the thread and pass it through. Pick up and pass through. Take a little break now, and I’ll teach you the two kinds of stitches, the knit stitch and the purl stitch. Nod to me if you understand.’

And so began the eagle king’s long year of knitting, and the toil was made even more onerous by using nettles for yarn and having to abstain from speaking and smiling. But, as he expected, it was his subjects who posed the biggest problem. And they had reason enough to be resentful. Him not smiling worried them the least; eagles, as we know, are not famous for their sense of humour. But him not speaking made for a serious problem. If only his reason had been pride and loftiness they would have forgiven him – he was the king of the eagles, after all. But hour after hour, day after day and month after month he just sat on his throne of stone, flightless, wordless, and knitted! He flew only after midnight, and then it was to cemeteries to pick nettles for knitting those shirts. The fingers on his left hand were covered with blisters, but he kept on knitting in silence with a dull look in his eyes. The eagles saw this as complete and utter decadence.

They began to whisper about him, and soon they were gossiping openly. Still he held his tongue and knitted. Now the eagles called an urgent assembly. Angry voices went up: ‘We are sick of this ruler! Oust him!’ He was calmly knitting the third shirt, with the other two lying finished beside him. ‘This is an insult!’ ‘He’s mocking us!’ ‘What a disgrace!’ ‘Depose him!’ ‘Lynch him!’ The threats became more severe by the minute as a circle of eagles drew tighter around him.

All of a sudden, the sky darkened and three white swans came down to land in the small space that remained around him and meekly bowed their long necks. He quickly cast the shirts over their heads and, to the wonder of all those present, except himself, the swans turned into Eliza and her two sisters. What a beautiful sight! The girls were gorgeous, and their shirts were like tunics that showed off their svelte yet curvaceous bodies. Tears of joy rolled down Eliza’s cheeks as she told the curious listeners of the sisters’ rousing odyssey, caused by their stepmother-witch and her bad magic, and the ordeal the eagle king had gone through for her sake.

‘Move back, all of you. Give her room to breathe!’ the eagles now heard their ruler’s voice for the first time in a year, and it was as resolute and confident as before. They made way for him, and he went up to Eliza and hugged her tight. He began to caress her and soon noticed that, instead of a left arm, she still had a wing: ‘your poor arm! I’ve failed you. I didn’t finish the last sleeve.’

‘Don’t be sad. I’ll wear this swan’s wing with pride, as a symbol of your selfless love. And we’ll complement each other when we do what lovers do.’

They finished the court and family formalities with the king’s ministers as quickly as they could. Then his mother (who reminded all who couldn’t escape her company of her vital role in the knitting saga) and the sisters all undressed and went to bed.

‘What’s so funny?’ he asked, a little snubbed, when he saw Eliza grinning.

‘The birthmark, my dear – the birthmark on your penis. Now, just before we get intimate, I was checking that it’s on the right-hand side.’

‘What the...’

‘You see, there’s a belief among our people that those with a birthmark on the left lean one way, so to speak, and those with it on the right lean another... so I just wanted to check. But now we can make love. My kisses will put a smile back on your face.’

Her voice went husky, as if there was a fluttering bird in her throat that wanted to escape. ‘Oh my God,’ the man with one wing muttered before getting down to business. And it was much better than in his wildest dreams.

And so the two of them lived happily for many, many years, until the end of their lives. Especially him. Eliza watched over him until her death. He was eighty when she died, having inherited his mother’s longevity, and his son, the heir to the throne, made sure he lacked nothing. Even his fading memory became a boon, for he felt carefree, as if he lived in a second childhood filled with fantasies and mythical creatures from distant, fairy-tale worlds. In old age, when he became ever more simple-minded, his imagination gained two powerful wings for antics and frivolity.

Now and again, accompanied by some of his caring servants, he would climb a hill that seemed strangely familiar (where did he know it from?) and sit on a rock there amidst a somehow familiar clearing. Taking the occasional bite of his favourite Turkish delight with coconut, tasty and soft enough for his toothless jaws, he would stare at the sky, where large and small clouds were in flight, changing shape from a horse into an elephant, an elephant into a train, a train into a snake – and so on, and so forth, almost without end.