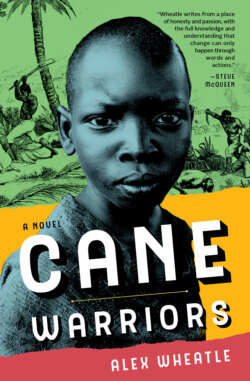

Читать книгу Cane Warriors - Alex Wheatle - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

MAMA

I sat down for a long while and closed my eyes. I imagined plunging my billhook into Misser Master’s chest. I saw the blood gushing out of his torso. I had seen many dead black bodies but I was yet to see the death mask of a white man. Could me really tek de last breath of one of dem? Do dem bleed red like we? When dem dead, do dem eyes look like somebody steal de light of dem?

I took a few moments to steady my nerves before starting for the bush. I used my fingers to climb up a steep bank. Twice I slid back down but I managed to secure a footing and pull myself up. I could see the fire lamps of the big house and outhouses through the trees and undergrowth. I had to lie very flat and still in the long grass as two overseers went by below me. I recognized one of them: Misser Penceton, he was the chief overseer and he lived in a big cabin forty steps away from Misser Master’s big house.

I tried to control my breathing. They paused for a bit, talking about their homeland, the big mansions they wanted to build, and the women they wanted to marry. If they glanced up for one short moment then I’d be flogged by the tall post at the top of the hill where everyone could see. Misser Master enjoyed spectacles like that.

I thought about crawling back and returning to my hut. But I had made it so far. I had to see Mama. Finally, the two men strolled on.

I skirted the front lawns and vegetable plots of the mansion where Tacky did his work. I crept by the overseers’ huts before sliding down a dry muddy slope that led to a gully. A stream cut a jagged path through the hard earth. I took a moment to drink and wet my face. It was refreshing and cool. The pit toilet was dug nearby and the stench filled my mouth, nostrils, and chest. The house-slave huts were placed beyond the pit toilet next to the hog pen. I heard the cocks cluck-clucking in the distance. For a moment the idea of stealing a chicken entered my head—my mouth watered—but I thought better of it. I made my way to the third hut of five and tapped on the open window. It was dark inside. “Mama!”

No response.

A baby cried in the end cabin. A mother sang Akan words to it.

“Mama,” I called, this time a little louder.

I heard somebody climbing to their feet. I hoped they hadn’t moved her.

“Moa? Ah you dat?”

“Yes, Mama.”

“Hold on ah liccle.”

“Is dat Moa outside?” another voice asked. It was Hamaya. She had shared my mother’s house-slave cabin since her parents died. I wondered for how long Misser Masser would allow her to sleep there. “Cyan me see him?”

“No, Hamaya,” replied Mama. “It best if you try catch sleep again.”

“But me want to see him.”

Mama didn’t respond.

“By de next fat moon dem might come for me, Moa,” called out Hamaya. “Dem cyan’t do anyting to me if me was by de dark side of de tall hilltop.”

“Hush you mout’,” scolded Mama.

Hamaya’s words tore into my chest. But me job is to kill Misser Donaldson, not to tek Hamaya’s good hand and lead her to de other side of de long mountain.

I strained my eyes into the night, trying to check for any sign of overseers. All seemed well. Mama emerged out of her cabin. “Come, Moa,” she said. “We’ll talk beside de pit toilet—de white mon nuh go near there.”

“De flies nuh mind,” I said.

Mama aimed her words into her hut: “Hamaya, stay where you be. Nuh follow we.”

“Where’s Hopie?” I asked.

“She sleeping,” Mama replied. “Me nuh want to wake her. She might get ah liccle excitable and holler and scream when she sight you. De same could be said for Hamaya. She really sweet ’pon you.”

I followed Mama to the pit toilet. The stink filled my nose and I almost sneezed. Flies hummed above our heads. Mama smiled and gave me a quick hug.

“Me should really beat de good sense back into you!” she said. “If Misser Master or Misser Penceton catch you here, you back will taste de ripper again. You nuh have no good sense, Moa?”

“Me had to see you, Mama.”

Her tone was angry. “Why?”

Mama was sweating. Maybe not from the humidity but from the worries she always carried, though she had kind eyes still. A white head-rag covered her hair. Her fingers were broader than mine and the night garment she wore was thick. Nothing covered her hard feet.

I took a deep breath. “We’re going to bruk outta here ’pon Easter Sunday—when de sun tek ah dip.”

My mother thought about it. I expected her to disapprove just like Papa.

“Ah true?” she said. Hope was in her voice.

“Yes, Mama, ah true.”

She swatted a fly and seized me with her eyes. She grabbed my shoulders and I felt the strength of her grip. “You have me blessing,” she said. “Tek you good foot and leave dis land. Never come back.”

“Me was t’inking dat you and Hopie would come wid me,” I said.

Mama laughed. “Ah crazy talk you ah talking! How is me old foot and liccle Hopie going to keep up wid you and fight de white mon?”

“But Mama . . . me nuh want to leave you here—”

“Listen me good, Moa. Me nuh want you to fill you head wid Hopie and me. You must forget about we. Nuh you t’ink dat after you gone me will smile at nighttime? And me will say to meself at least one of me pickney leave dis wicked place. And maybe he be at someplace better. Me have to believe dat better must come for you. You must leave me wid dat hope inna me head.”

“But Mama—”

“Talk no more, Moa. You must do what you have to do. You nuh t’ink Miss Pam ever dream of her sons escaping from dis place? She never live to see it. Me want to live and hear de story and me will tell de tale to liccle Hopie.”

“Me hear Louis talk about dis Dreamland,” I said. “And Tacky too.”

“Nuh worry you pretty liccle head about Dreamland,” said Mama. She fixed a hard stare on me. “Just tek you swift foot and go’long from dis wicked place.”

“But me might not see you again, Mama.”

She thought about it and wiped the sweat from her forehead. “And dat will be ah good ting.”

“Ah good ting?” I repeated.

“Yes, mon,” Mama said. “Why do you t’ink Miss Gloria smile and show her good teet’ every morning?”

“Me nuh know, Mama.”

“Becah her eldest son Midgewood mek him escape.”

“Me never know Miss Gloria had ah son call Midgewood.”

“Yes, mon,” Mama confirmed. “Him now twenty-t’ree years old. None of we talk about it becah Misser Master get vex when he hears him name. And Misser Master tell Misser Penceton dat dem must whip anybody who mention him name. Midgewood was broad and strong. One time me overhear Misser Master saying him was wort’ ah whole cartload of money. But Midgewood lef’ and gone and dat’s why Miss Gloria smile ah morning time.”

“She nuh smile dis morning,” I pointed out.

“Dat’s becah of Miss Pam,” Mum explained. “Ever’body’s heart well heavy like fat donkey backside wid dat news. Plenty eye-water ah fall. She was ever’body’s mama.”

“Louis and plenty other mon want to tek dem revenge,” I said.

Mama thought about it. “Good!”

I gazed into her eyes. It might be the last time I look into them. “So me have you blessing?”

Tears rolled down Mama’s cheeks. She cradled my jaw with both hands. It felt good to feel her touch. Suddenly her eyes came alive. “Run, Moa! Nuh turn back! Look for Midgewood if you cyan. Mek me smile every morning when me there inna de cookhouse or de smokehouse. And when Misser Master’s wife cuss me and bruk her hand across me face if de dinner nuh cook right. Sometime me so tired, sleep catches me when me stand up and stir de big pot. And it so damn hot inna de cookhouse dat me surprise me nuh look like roast hog. But if you run away, dat will give me plenty hope.”

“Me will try me best, Mama.”

“Yes, Moa. And when you gone me going to tell liccle Hopie about you. Yes, mon. Misser Master have dis big book inna de big house. Me see Misser Master pickney reading it. Me want to teach liccle Hopie to read and write so she cyan tell we story.”

“Nuh let Hopie forget me,” I said.

“Me won’t,” Mama replied. “Now, tek you good foot and go back to you own hut. Be careful. De overseer dem sometimes walk at strange times under de broad moon.”

“Nuh worry, Mama,” I said. “Me know de back way where de white mon bad toe nuh tread.”

We hugged quickly.

Before I started, I concentrated my ears and peered into the blackness around me. “Let Asase Ya smile ’pon you, Mama.”

“Ah! You remember we mama god.” She smiled. “Let she protect you too and nuh let you pickney forget her.”

“Me won’t, Mama.”

I turned. My first few steps were short.

“Kwan so dwoodwoo,” called Mama.

I didn’t face her. I stood still. “What does dat mean, Mama?”

“Safe travel.”