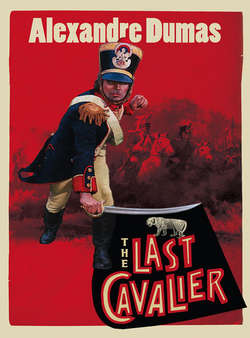

Читать книгу The Last Cavalier: Being the Adventures of Count Sainte-Hermine in the Age of Napoleon - Александр Дюма, Alexandre Dumas - Страница 11

VII Blues and Whites

ОглавлениеROLAND STOOD ALONE for a moment. He was now free, but he had been disarmed literally by his fall and figuratively by his word. He contemplated the little mound where he and Cadoudal had shared a breakfast; it was still covered with the cloak that had served as a tablecloth. From there he could survey the whole battlefield, and if his eyes had not been clouded by tears of shame, he would not have missed the slightest detail.

Like the demon of war, invulnerable and relentless, Cadoudal was standing upright on his horse in the midst of the fire and smoke.

As the heat of his anger dried his tears of shame, Roland noticed more. Out in the fields where green wheat was beginning to sprout, he counted the bodies of a dozen Chouans who lay scattered here and there on the ground. But the Republicans, in their compact formation on the road, had lost more than twice that number.

The wounded on both sides dragged themselves into the open field, where, like broken serpents, they tried to rise and continue fighting, the Republicans with their bayonets, the Chouans with their knives. Or they would reload their guns, then manage to get up on one knee, and fire, and fall back again onto the ground.

On both sides the combat was relentless, unceasing, pitiless. Civil war, a merciless and unforgiving civil war, was translating its hate into blood and death across the battlefield.

Cadoudal rode back and forth through the human redoubt. From twenty paces he’d fire, sometimes with his pistols, sometimes from a double-barreled gun that he’d then toss to a Chouan for reloading. Every time he shot, a man would fall. General Harty honored Cadoudal’s maneuvers by ordering an entire platoon to fire at him.

In a wall of flame and smoke, he disappeared. They saw him fall, him and his horse, as if struck by lightning.

Ten or twelve men rushed out of the Republican ranks, but they were met by an equal number of Chouans. In the terrible hand-to-hand combat, the Chouans with their knives seemed to have the upper hand.

Then, suddenly, Cadoudal was again among them; standing in his stirrups, he wielded a pistol in each hand. Two men fell, two men died.

Thirty Chouans joined him to form a sort of wedge. Now wielding a regular-issue rifle, using it as a club, Cadoudal led his thirty men into their enemy’s ranks. With each swing the giant felled a man. He broke through the Blues’ battalion, and Roland saw him appear on the Republican side of the battle lines. Then, like a wild boar that turns back on a fallen hunter to rip out his entrails, Cadoudal reentered the fray and widened the breach.

General Harty rallied twenty men around him. Holding their bayonets in front of them, they bore down on the Chouans who had formed a circle around their general. Harty’s horse had been disemboweled, so with his clothing full of bullet holes and blood flowing from two wounds, he marched on foot with his twenty men. Ten of them fell before they could break the Chouan circle, but Harty made it through to the other side.

Ready though the Chouans were to pursue him, Cadoudal in a thunderous voice called out: “You should not have let him pass, but since he’s already through, let him withdraw freely.” The Chouans obeyed their leader as if his words were sacred.

“And now,” Cadoudal cried, “let the firing cease! No more killing! Only prisoners!”

And with that, everything was over.

In that horrible war both sides shot their prisoners: the Blues because they considered the Chouans and the Vendeans to be brigands; the Whites because they didn’t know what to do with the Republicans they captured.

The Republicans tossed aside their guns to avoid handing them over to their enemy. When the Chouans approached them, they opened their cartridge pouches to show that they had spent their last ammunition.

Cadoudal started his march over to Roland.

During the final stages of the battle, the young man had remained seated; with his eyes fixed on the struggle, his hair wet with sweat, his breathing pained and heavy, he had waited. When he saw that fortune had turned against the Republicans and him, he had put his hands to his head and dropped facedown to the ground.

Roland seemed not to hear Cadoudal’s footsteps when he walked up to him. Then slowly the young officer raised his head; tears were coursing down both cheeks.

“General,” said Roland. “Dispose of me as you will. I am your prisoner.”

“Well,” laughed Cadoudal, “we cannot make a prisoner of the First Consul’s ambassador, but we can ask him to do us a service.”

“What service? Just give the order.”

“I don’t have enough ambulances for the wounded. I don’t have enough prisons for the prisoners. Take it upon yourself to lead the Republican soldiers, both the prisoners and the wounded, back to Vannes.”

“What are you saying, General?” Roland exclaimed.

“I put them in your care. I regret that your horse is dead. I am sorry too that my own horse was killed, but Branche-d’Or’s horse is still available. Please accept it.”

Cadoudal saw that the young man was reluctant. “In exchange, do I not still have the horse you left in Muzillac?” George said.

Roland understood that he had no choice but to match the noble character of the person he was dealing with.

“Will I see you again, General?” he asked, getting to his feet.

“I doubt it, monsieur. My operations call me to the Port-Louis coast, and your duty calls you back to the Luxemburg Palace.” (At that time, Bonaparte was still living there.)

“What shall I tell the First Consul, General?”

“Tell him what you saw, and tell him especially that I consider myself greatly honored that he has promised to see me.”

“And given what I have seen, monsieur, I doubt that you will ever need me,” said Roland. “But in any case, remember that you have a friend close to General Bonaparte.” He extended his hand to Cadoudal.

The Royalist leader took his hand with the same candor and confidence he had shown before the battle. “Good-bye, Monsieur de Montrevel,” he said. “I’m sure there’s no need for me to remind you to do justice to General Harty? A defeat of that kind is as glorious as a victory.”

Branche-d’Or’s horse had meanwhile been brought to the colonel. He leaped into the saddle. Taking one last look around the battlefield, Roland heaved a great sigh. With a final good-bye to Cadoudal he then started off at a gallop across the fields toward the Vannes highway, where he would await the cart with the prisoners and the wounded that he had been charged with taking back to General Harty.

Each man had received ten pounds on Cadoudal’s orders. Roland could not help but think that Cadoudal was being generous with the Directory’s money, sent to the West by Morgan and his unfortunate companions. And Morgan’s companions had paid for that money with their heads.

The next day, Roland was in Vannes. In Nantes, he took the stagecoach to Paris and arrived two days later.

As soon as Bonaparte learned that he was back, he summoned Roland to his study.

“Well, then,” Bonaparte asked when he appeared, “what about this Cadoudal? Was he worth the trouble you put yourself through?”

“General,” Roland answered, “if Cadoudal is willing to come over to our side for one million, give him two, and don’t sell him to anyone else even for four.”

Colorful as the answer was, it was not sufficient for Bonaparte. So Roland had to recount in detail his meeting with Cadoudal in Muzillac, their night march under the singular protection of the Chouans, and finally the combat, in which, after prodigious feats of courage, General Harty had yielded to the Royalists.

Bonaparte was jealous of such men. Often he had spoken with Roland about Cadoudal, in the hope that some defeat would encourage the Breton leader to abandon the Royalist party. But soon Bonaparte was crossing the Alps and concentrating not on civil war but on foreign wars. He had crossed the Saint-Bernard pass on the 20th and 21st of May and the Tessino River at Turbigo on the 31st. On June 2nd he entered Milan. After conferring with General Desaix, who was just back from Egypt, he spent the night of the 11th in Montebello. On the 12th, Bonaparte had set his army in position on the Scrivia and finally, on June 14, 1800, he had waged the Battle of Marengo. There, tired of life, Bonaparte’s aide-de-camp Roland had been killed in the explosion he himself had ignited when he set fire to a munitions wagon.

Bonaparte no longer had anyone to talk to about Cadoudal. Still, he thought often about the Breton brigand. Then, early in February 1801, the First Consul received a letter from Brune containing this letter from Cadoudal:

General,

If I had to fight only the 35,000 men you currently have in the Morbihan, I would not hesitate to continue the campaign as I have done for more than a year, and by a series of lightning-quick movements, I would destroy them to the last man. But others would immediately replace them, and prolonging the war would only result in the greatest of disasters.

Please set the date for a meeting, giving your word of honor. I shall come to see you without fear, alone or with others. I shall negotiate for me and for my men, and I shall be tough for them alone.

George Cadoudal

Beneath Cadoudal’s signature, Bonaparte wrote: “Set a meeting promptly. Agree to all his conditions, provided that George and his men lay down their arms. Insist that he come see me in Paris, and give him a safe-conduct. I want to see this man close-up and form my own judgment of him.” And in his own hand he addressed the letter “To General Brune, Commander-in-Chief of the Western Army.”

As it happened, General Brune was camped on the same road between Muzillac and Vannes where the Battle of the One Hundred had taken place two years before. There General Harty had been defeated, and there Cadoudal now appeared before General Brune. Brune extended his hand and led Cadoudal, along with his aides-de-camp Sol de Grisolles and Pierre Guillemot, across a trench where all four sat down.

Their discussion was just about to begin when Branche-d’Or arrived with a letter so important (so he’d been told) that he thought he should deliver it immediately to the general, wherever he happened to be. The Blues had allowed him passage to his leader, who, with Brune’s permission, took the letter and quickly perused it.

His face betraying no emotion, Cadoudal finished the letter, folded it back up, and tossed it into his hat. Then he turned toward Brune. “I’m all ears, General,” he said.

Ten minutes later, everything was decided. The Chouans, officers and soldiers alike, would all return freely to their homes without harassment, not then or in the future, and they would not take up arms again except by direct orders from Cadoudal himself.

As for Cadoudal himself, he asked that he be granted the right to sell the few parcels of land, the mill, and the house that belonged to him and with the money from the sale be allowed to settle in England. He asked for no indemnity whatever.

As for a meeting with the First Consul, Cadoudal declared that he would consider it a great honor. He said he’d be ready to go to Paris as soon as he had arranged with a notary in Vannes for the sale of his property and with Brune for a safe-conduct.

As for his two aides-de-camp, other than permission for them to accompany him to Paris so they could witness his meeting with Bonaparte, he asked only for the same conditions he had obtained for his men—pardon for the past, safety for the future.

Brune asked for pen and ink.

The treaty was written on a drum. It was shown to George, who then signed it, as did his aides-de-camp. Brune signed last and gave his personal guarantee that the document would be faithfully executed.

While a copy was being made, Cadoudal pulled the letter he had received out of his hat. Handing it to Brune, he said, “Read this, General. You will see that I did not sign the treaty because I needed money.” For indeed, the letter from England announced that the sum of three hundred thousand francs had been deposited with a banker in Nantes, with the order that the funds be made available to George Cadoudal.

Taking the pen, Cadoudal wrote on the second page of the letter: “Sir, Send the money back to London. I have just signed a peace treaty with General Brune, and consequently I am unable to receive money destined for making war.”

Three days after the treaty had been signed, Bonaparte had a copy in hand, along with Brune’s notes detailing the meeting.

Two weeks later, George had sold his property for a total of sixty thousand francs. On February 13, he alerted Brune that he would be leaving for Paris, and on the 18th Le Moniteur, the official record, published this announcement:

George will be going to Paris to meet with the government. He is a man thirty years of age. The son of a miller, fond of battle, having a good education, he told General Brune that his whole family had been guillotined but that he wished to be associated with the government. He said that he wanted his links with England to be forgotten, and that he had only sought out England in order to oppose the regime of 1793 and the anarchy that seemed then about to devour France.

Bonaparte was right to say, when Bourrienne offered to read him the French newspapers, “That’s enough, Bourrienne. They say only what I let them say.”

The newspaper report of course had come directly from Bonaparte’s office, and with customary skill it combined both foresight and hate. In his foresight, the First Consul was improvising Cadoudal’s rehabilitation by attributing to him the desire to serve the government. And in his hate, he was charging him with crimes against the regime of 1793.

On February 16, Cadoudal arrived in Paris. On the 18th, he read the brief piece about him in Le Moniteur. For a moment he was tempted to leave without seeing Bonaparte, hurt as he was by the newspaper’s tone. But he decided it was better to accept the proposed audience and make his profession of faith to the First Consul. Accompanied by two witnesses, his officers Sol de Grisolles and Pierre Guillemot, he would go to the Tuileries as if he were going to a duel. Through the War Ministry, he sent word to the Tuileries that he had arrived in Paris. He received back a letter setting the audience for the next day, on February 19, at nine in the morning.

And that was the meeting to which the First Consul Bonaparte was hurrying so eagerly, once he had sorted out Josephine’s debts.