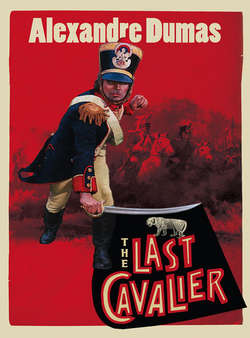

Читать книгу The Last Cavalier: Being the Adventures of Count Sainte-Hermine in the Age of Napoleon - Александр Дюма, Alexandre Dumas - Страница 7

III The Companions of Jehu

ОглавлениеIT WAS NOT THE FIRST TIME that Bonaparte tried to bring Cadoudal back to the side of the Republic in order to gain that formidable partisan’s support.

An incident that had occurred on Bonaparte’s return from Egypt was imprinted deeply in his memory.

On the 17th Vendémiaire of the year VIII (October 9, 1799), Bonaparte had, as everyone knows, disembarked in Fréjus without going through quarantine, although he was coming from Alexandria.

He had immediately gotten into a coach with his trusted aide-de-camp, Roland de Montrevel, and left for Paris.

The same day, around four in the afternoon, he reached Avignon. He stopped about fifty yards from the Oulle gate, in front of the Hôtel du Palais-Egalité, which was just beginning again to use the name Hôtel du Palais-Royal, a name it had held since the beginning of the eighteenth century and that it still holds today. Urged by the need all mortals experience between four and six in the afternoon to find a meal, any meal, whatever the quality, he got down from the coach.

Bonaparte was in no particular way distinguishable from his companion, save for his firm step and his few words, yet it was he who was asked by the hotel keeper if he wished to be served privately or if he would be willing to eat at the common table.

Bonaparte thought for a moment. News of his arrival had not yet spread through France, as everyone thought he was still in Egypt. His great desire to see his countrymen with his own eyes and hear them with his own ears won out over his fear of being recognized; besides, he and his companion were both wearing clothing typical for the time. Since the common table was already being served and he would be able to dine without delay, he answered that he would eat at the common table.

He turned to the postilion who had brought him. “Have the horses harnessed in one hour,” he said.

The hotelier showed the newcomers the way to the common table. Bonaparte entered the dining room first, with Roland behind him. The two young men—Bonaparte was then about twenty-nine or thirty years old, and Roland twenty-six—sat down at the end of the table, where they were separated from the other diners by three or four place settings.

Whoever has traveled knows the effect created by newcomers at a common table. Everyone looks at them, and they immediately become the center of attention.

At the table were some regular customers, a few travelers en route by stagecoach from Marseille to Lyon, and a wine merchant from Bordeaux who was staying temporarily in Avignon.

The great show the newcomers had made of sitting off by themselves increased the curiosity of which they were the object. Although the man who’d entered second was dressed much the same as his companion—short leather pants and turned-down boots, a coat with long tails, a traveler’s overcoat and a wide-brimmed hat—and although they appeared to be equals, he seemed to show a noticeable deference to his companion. The deference was obviously not due to any age difference, so no doubt it was owed by a difference in social position. Furthermore, he addressed the first man as “citizen,” while his companion called him simply Roland.

What usually happens in such situations happened here. After a moment of interaction with the newcomers, everyone soon looked away, and the conversation, interrupted for a moment, resumed as before.

The subject of the conversation greatly interested the newly arrived travelers, as their fellow guests were talking about the Thermidorian Reaction and the hopes that lay in now reawakened Royalist feelings. They spoke openly of a coming restoration of the House of Bourbon, which surely, with Bonaparte being tied up as he was in Egypt, would take place within six months.

Lyon, one of the cities that had suffered hardest during the Revolution, naturally stood at the center of the conspiracy. There a veritable provisional government—with its royal committee and royal administration, a military headquarters and a royal army—had been set up.

But, in order to pay these armies and support the permanent war effort in the Vendée and Morbihan, they needed money; and lots of it. England had provided a little but was not overly generous, so the Republic was the only source of money available to its Royalist enemies. Instead of trying to open difficult negotiations with the Republic, which would have refused assistance in any case, the royal committee had organized roving bands of brigands who were charged with stealing tax revenues and with attacking the vehicles used for transporting public funds. The morality of civil wars, very loose in regard to money, did not consider stealing from Treasury stagecoaches as real theft, but rather as a military operation.

One of these bands had chosen the route between Lyon and Marseille, and as the two travelers were taking their place at the common table, the subject of conversation was the hold-up of a stagecoach carrying sixty thousand francs of government funds. The hold-up had taken place the day before on the road from Marseille to Avignon, between Lambesc and Port-Royal.

The thieves, if we can use that word for such nobly employed stagecoach robbers, had even given the coachman a receipt for what they took. They had made no attempt, either, to hide the fact that the money would be crossing France by more secure means than his stagecoach and that it would buy supplies for Cadoudal’s army in Brittany.

Such actions were new, extraordinary, and almost impossible for Bonaparte and Roland to believe, for they had been absent from France for two years. They did not suspect what deep immorality had found its way into all classes of society under the Directory’s bland government.

This particular incident had taken place on the very same road Bonaparte and his companion had just traveled, and the person telling the story was one of the principal actors in that highway drama: the wine merchant from Bordeaux.

Those who seemed to be most interested in all the details, aside from Bonaparte and his companion, who were happy simply to listen, were the people traveling in the stagecoach that had just arrived and was soon to leave. As for the other guests, the people who lived nearby, they had become so accustomed to these episodes that they could have been giving the details instead of listening to them.

Everyone was looking at the wine merchant, and, we must say, he was up to the task as he courteously answered all the questions put to him.

“So, Citizen,” asked a heavyset man whose tall, skinny, shriveled-up wife was pressing up against him, pale and trembling in fear, so much so that you could almost hear her bones knocking together. “You say that the robbery took place on the road we’ve just taken?”

“Yes, Citizen. Between Lambesc and Pont-Royal, did you notice a place where the road climbs between two hills, a place where there are many rocks?”

“Oh, yes, my friend,” the woman said, holding tight to her husband’s arm. “I did see it, and I even said, as you must remember, ‘This is a bad place. I’m glad we’re coming through during the day and not at night.’”

“Oh, madame,” said a young man whose voice exaggerated the guttural pronunciation of the time and who seemed to exercise a royal influence on the conversation of the common table, “you surely know that for the gentlemen called the Companions of Jehu there is no difference between day and night.”

“Indeed,” said the wine merchant, “it was in full daylight, at ten in the morning, that we were stopped.”

“How many of them were there?” the heavyset man asked.

“Four of them, Citizen.”

“Standing in the road?”

“No, they appeared on horseback, armed to the teeth and wearing masks.”

“That is their custom, that is their custom,” said the young man with the guttural voice. “And then they must have said, did they not?, ‘Don’t try to defend yourselves, and no harm will come to you. All we are after is the government’s money.’”

“Word for word, Citizen.”

“Yes,” continued the man who seemed to have all the information. “Two of them got down, handed their bridles to their companions, and asked the coachman to give them the money.”

“Citizen,” the large man said in amazement, “you’re telling the story as if you had witnessed it yourself!”

“Perhaps the gentleman was there,” said Roland.

The young man turned sharply toward the officer. “I don’t know, Citizen, if you intend to be impolite with me. We can speak about that after dinner. But, in any case, I am pleased to say that my political opinions are such that, unless you were intending to insult me, I would not consider your suspicion as an offense. However, yesterday morning at ten o’clock, when those gentlemen were stopping the stagecoach four leagues away, these gentlemen here can attest to the fact that I was having lunch at this very table, between the same two citizens who at this moment are doing me the honor of sitting at my right and my left.”

“And,” Roland continued, speaking this time to the wine merchant, “how many of you were in the stagecoach?”

“There were seven men and three women.”

“Seven men, not counting the coachman?” Roland repeated.

“Of course,” the man from Bordeaux answered.

“And with eight men you let yourself be robbed by four bandits? I congratulate you, monsieur.”

“We knew whom we were dealing with,” the wine merchant answered, “and we were not about to try to defend ourselves.”

“What?” Roland replied. “But you were dealing with brigands, with bandits, with highway robbers.”

“Not at all, since they had introduced themselves.”

“They had introduced themselves?”

“They said, ‘We are not brigands; we are the Companions of Jehu. It is useless to try to defend yourselves, gentlemen; ladies, don’t be afraid.’”

“That’s right,” said the young man at the common table. “It is their custom to let people know, so there can be no mistake.”

“Well,” Roland continued, while Bonaparte kept silent, “who is this citizen Jehu who has such polite companions? Is he their captain?”

“Sir,” said a man whose clothing looked very much like that of a secular priest, and who seemed to be a resident of the city as well as a regular at the common table, “if you were more acquainted than you seem to be in reading Holy Scripture, you would know that this citizen Jehu died some two thousand six hundred years ago, so that consequently, at the present time, he is unable to stop stagecoaches on the highway.”

“Sir priest,” Roland said, “since, in spite of the sour tone you are currently using with me, you seem to be well educated, allow a poor ignorant man to ask for some details about this Jehu who died twenty-six hundred years ago but is nevertheless honored by having companions who carry his name.”

“Sir,” the man of the church answered in the same clipped tone, “Jehu was a king of Israel, consecrated by Elisha on the condition that he punish the crimes of the house of Ahab and Jezebel and that he put to death all the priests of Baal.”

“Sir priest,” the young officer laughed, “thank you for the explanation. I have no doubt that it is accurate and certainly very scholarly. Except I have to admit that it has taught me very little.”

“What do you mean, Citizen?” said the regular customer at the table. “Don’t you understand that Jehu is His Majesty Louis XVIII, may God preserve him, consecrated on the condition that he punish the crimes of the Republic and that he put to death all the priests of Baal—that is, all the Girondins, the Cordeliers, the Jacobins, the Thermidorians; all those people who have played any part over the last seven years in this abominable state of affairs that we call the Revolution!”

“Well, sure enough!” said Roland. “Indeed, I am beginning to understand. But among those people the Companions of Jehu are supposed to be fighting, do you include the brave soldiers who pushed the foreigners back out of France and the illustrious generals who led the armies in the Tyrol, the Sambre-et-Meuse, and Italy?”

“Yes. Those men, and especially those men.”

Roland’s eyes grew hard, his nostrils dilated, he pinched his lips and started to stand up. But his companion grabbed his coat and pulled him back down, and the word “fool,” which he was about to throw in the face of his interlocutor, stayed between his teeth.

Then, with a calm voice, the man who had just demonstrated his power over his companion spoke for the first time. “Citizen,” he said, “please excuse two travelers who have just come from the ends of the earth, as far away as America or India, who have been out of France for two years, who don’t know what’s happening here, and who are eager to learn.”

“Tell us what you would like to know,” the young man asked, apparently having paid only the slightest attention to the insult Roland had been about to spit at him.

“I thought,” Bonaparte continued, “that the Bourbons were completely reconciled to exile. I thought the police were sufficiently well organized to keep bandits and robbers off the highways. And finally, I thought that General Hoche had completely pacified the Vendée.”

“But where have you been? Where have you been?” said the young man with a loud laugh.

“As I told you, Citizen, at the ends of the earth.”

“Well, then. Let me help you understand. The Bourbons are not rich; the émigrés, whose property has been sold, are ruined. It is impossible to pay two armies in the West and to organize one in the Auvergne mountains without any money. So the Companions of Jehu, by stopping stagecoaches and pillaging the coffers of our tax officers, have set themselves up as tax collectors for the Royalist generals. Just ask Charette, Cadoudal, and Teyssonnet.”

“But,” ventured the Bordeaux wine merchant, “if the gentlemen calling themselves the Companions of Jehu are only after the government’s money.…”

“Only the government’s money, not anyone else’s. Never have they robbed an ordinary citizen.”

“So yesterday,” the man from Bordeaux continued, “how did it happen, then, that along with the government’s money they also carried off a bag containing two hundred louis that belonged to me?”

“My dear sir,” the young man answered, “I’ve already told you that there must have been some mistake, and as sure as my name is Alfred de Barjols, that money will be returned to you some day.”

The wine merchant sighed deeply and shook his head like a man who, in spite of the reassurances people are giving him, still is not totally convinced.

But at that moment, as if the guarantee given by the young man who had revealed his own name and social rank had awakened the sensibilities of those for whom he was giving his guarantee, a horse galloped up to the front door. They could hear footsteps in the corridor; the dining room door was flung open, and a masked man, armed to the teeth, appeared in the doorway.

All eyes turned to him.

“Gentlemen,” he said, his voice breaking the deep silence that greeted his unexpected appearance, “is there among you a traveler named Jean Picot who was in the stagecoach that was stopped between Lambesc and Port-Royal by the Companions of Jehu?”

“Yes,” said the wine merchant in astonishment.

“Might you be that man, monsieur?” the masked man asked.

“That’s me.”

“Was nothing taken from you?”

“Yes, there was. I had entrusted a sack of two hundred louis to the coachman, and it was taken.”

“And I must say,” added Alfred de Barjols, “that just now this gentleman was telling us about his misfortune, considering his money lost.”

“The gentleman was mistaken,” said the masked stranger. “We are at war with the government, not with ordinary citizens. We are partisans, not thieves. Here are your two hundred louis, monsieur, and if ever a similar error should take place in the future, just remember the name Morgan.”

And with those words the masked man set down a bag of gold to the right of the wine merchant, politely said good-bye to those seated around the table, and walked out, leaving some of them in terror and the others in stupefaction at his daring.

At that moment word came to Bonaparte that the horses were harnessed and ready.

He stood and asked Roland to pay.

Roland dealt with the hotel keeper while Bonaparte got into the coach. Just as Roland was about to join his companion, he found Alfred de Barjols in his path.

“Excuse me, monsieur,” the young man said to him. “You were beginning to say something to me, but the word never left your lips. Might I know what kept you from pronouncing it?”

“Oh, monsieur,” said Roland, “the reason I held it back was simply that my companion pulled me back down by my coat pocket, and so as not to be disagreeable to him, I decided not to call you a fool.”

“If you intended to insult me in that way, monsieur, might I therefore consider that you have now done so?”

“If that should please you, monsieur.…”

“That does please me, because it offers me the opportunity to demand satisfaction.”

“Monsieur,” said Roland, “we are in a great hurry, my companion and I, as you can see. But I will be happy to delay my departure for an hour if you think one hour will be enough to settle this question.”

“One hour will be sufficient, monsieur.”

Roland bowed and hurried to the coach.

“Well,” said Bonaparte, “are you going to fight?”

“I could not do otherwise, General,” Roland answered. “But my adversary appears to be very accommodating. It should not take more than an hour. I shall hire a horse as soon as this business is over and shall surely catch up with you before you reach Lyon.”

Bonaparte shrugged.

“Hothead,” he said. And then, reaching out his hand, he added, “Try at least not to get yourself killed. I need you in Paris.”

“Oh, relax, General. Somewhere between Valence and Vienne I shall come tell you what happened.”

Bonaparte left.

About one league beyond Valence he heard a horse galloping behind him and ordered the coachman to stop.

“Oh, it’s you, Roland,” he said. “Apparently everything went well?”

“Perfectly well,” said Roland as he paid for his horse.

“Did you fight?”

“Yes, I did, General.”

“How?”

“With pistols.”

“And?”

“And I killed him, General.”

Roland took his place beside Bonaparte and the coach set off again at a gallop.