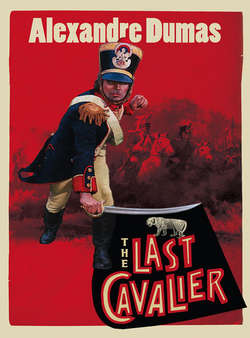

Читать книгу The Last Cavalier: Being the Adventures of Count Sainte-Hermine in the Age of Napoleon - Александр Дюма, Alexandre Dumas - Страница 25

XXI In Which Fouché Works to Return to the Ministry of Police, Which He Has Not Yet Left

ОглавлениеFOUCHÉ WENT BACK to his office furious. He still had a role to play, but the role was limited. Outside of the police, Fouché had only secondary power, which to him was of no real value. For nature had endowed him with crossed eyes so that he could look in two directions at once and with big ears that could hear things from all directions. Add to that his subtle intelligence and his temperament—nervous, irritable, worrying—all of which went wanting without his ministry.

And Bonaparte had hit upon the truly sensitive point. In losing the police, he was losing his control over gambling, so he was also losing more than two hundred thousand francs a year. Although Fouché was already extremely rich, he was always trying to increase his wealth even if he could never really enjoy it. His ambition to extend the boundaries of his domain in Pontcarré was no less great than Bonaparte’s to move back the borders of France.

Fouché threw himself into his armchair without a word to anyone. His facial muscles were quivering like the surface of the ocean in a storm. After a few minutes, however, they stopped twitching, because Fouché had found what he was looking for. The pale smile that lit up his face indicated, if not the return of good weather, at least a temporary calm. He grabbed the bell cord that hung above his desk and pulled it vigorously.

The office boy hurried in. “Monsieur Dubois!” Fouché shouted.

A moment later the door opened and Monsieur Dubois entered. Dubois had a calm, gentle face, with a kindly, unaffected smile, and he was scrupulously neat. Wearing a white tie and a shirt with cuffs, he pranced more than he walked lightly in, and the soles of his shoes slid over the carpet as if they were a dancing master’s.

“Monsieur Dubois,” said Fouché, throwing himself back in his armchair, “today I need all your intelligence and discretion.”

“I can vouch only for my discretion, Monsieur le Ministre,” he answered. “As for my intelligence, it has value only when guided by you.”

“Fine, fine, Monsieur Dubois,” said Fouché a little impatiently. “Enough compliments. In your service, is there a man whom we can trust?”

“First I need to know what we will be using him for.”

“Of course. He will travel to Brittany, where he will organize three bands of fire-setters. One fire, the largest, must be set on the road between Vannes and Muzillac; the other two, wherever he likes.”

“I’m listening,” said Dubois, noting that Fouché had paused.

“One of the bands will call itself Cadoudal’s band, and it will pretend to have Cadoudal himself at its head.”

“According to what Your Excellency is saying.…”

“I shall let you use those words for now,” said Fouché with a laugh, “especially since you’ve not much time left appropriately to use them.”

Dubois bowed, and, encouraged by Fouché, he went on: “According to what Your Excellency is saying, you need a man who can shoot if necessary.”

“That, and whatever else is necessary.”

Monsieur Dubois thought for a moment and shook his head. “I have no one like that among my men,” he said.

But, when Fouché gestured impatiently, Dubois recalled: “Wait a moment. Yesterday a man came to my office, a certain Chevalier de Mahalin, a fellow who was a member of the Companions of Jehu and who asks for nothing better, he says, than well-paid dangers. He is a gambler in every sense of the word, ready to risk his life as well as his money on a throw of the dice. He’s our man.”

“Do you have his address?”

“No. But he is coming back to my office today sometime between one and two o’clock. It is now one o’clock, so he must be there already or else he will be soon.”

“Go, then, and bring him back here.”

When Monsieur Dubois had left, Fouché pulled a file from its box and carried it over to his desk. It was the Pichegru file, and he studied it with the greatest attention until Monsieur Dubois returned with the man he’d talked about.

It was the same man who had visited Hector de Sainte-Hermine regarding the promises he’d made to his brother and who then had led him to Laurent’s band. Now disbanded, with nothing more to be done in Cadoudal’s cause, the good man was looking elsewhere for work.

He was probably between twenty-five and thirty years old, well built, and quite handsome. He had a pleasant smile, and you could have said he was likeable in every respect, except for a troubled and disturbing look in his eyes that often caused people he dealt with worry and concern.

Fouché examined him with a penetrating look that enabled him to take any man’s moral measure. In this man he could sense the love of money, great courage, though he seemed more ready to defend himself than to attack another, and the absolute will to succeed in any undertaking. That was exactly what Fouché was looking for.

“Monsieur,” said Fouché, “I have been assured that you would like to enter government service. Is that correct?”

“That is my greatest wish.”

“In what role?”

“Wherever there are blows to receive and money to be earned.”

“Do you know Brittany and the Vendée?”

“Perfectly well. Three times I have been sent to meet General Cadoudal.”

“Have you been in contact with those serving just beneath him?”

“With some of them, and particularly with one of Cadoudal’s lieutenants—he’s called George II because he looks like the general.”

“Damn!” said Fouché. “That might be useful. Do you believe you could raise three bands of about twenty men each?”

“It is always possible, in a region still warm from civil war, to raise three bands of twenty men. If the purpose is honorable, honest men will easily make up your sixty, and for them all you will need are grand words and elegant speech. If the purpose is less principled and demands secrecy, you will still be able to enlist mercenaries, but to buy their questionable consciences will cost you more.”

Fouché gave Dubois a look that seemed to be saying, “My good man, you have indeed come up with a real find.” Then, to the chevalier, he said, “Monsieur, within ten days we need three bands of incendiaries, two in the Morbihan and one in the Vendée, all three of them acting in Cadoudal’s name. In one of the bands a masked man must assume the name of the Breton general and do all that he can to convince the populace that he really is Cadoudal.”

“Easy, but expensive, as I have said.”

“Are fifty thousand francs enough?”

“Yes. Unquestionably.”

“So then, we are agreed on that point. Once your three bands have been organized, will you be able to go to England?”

“There is nothing simpler, given that my background is English and that I speak the language as well as I do my mother tongue.”

“Do you know Pichegru?”

“By name.”

“Do you have a means of getting introduced to him?”

“Yes.”

“And if I asked you how?”

“I would not tell you. After all, I need to keep some secrets; otherwise, I would lose all my value.”

“So you would. And so you will go to England, where you will check out Pichegru and try to discover under what circumstances he would be willing to come back to Paris. Were he to wish to return to Paris but finds money to be lacking, you will propose funds in the name of Fauche-Borel. Don’t forget that name.”

“The Swiss bookseller who has already made proposals to him in the name of the Prince de Condé; yes, I know him. And were he to wish to return to Paris and needs money, to whom should I turn?”

“To Monsieur Fouché, at his domain in Pontcarré. Not to the Minister of Police, the difference is important.”

“And then?”

“And then you will return to Paris for new orders. Monsieur Dubois, please count out fifty thousand francs for the chevalier. By the way, chevalier.…”

Mahalin turned around.

“If you should happen to meet Coster Saint-Victor, encourage him to come back to Paris.”

“Does he not risk arrest?”

“No, all will be forgiven, that I can affirm.”

“What shall I say to convince him?”

“That all the women in Paris miss him, and especially Mademoiselle Aurélie de Saint-Amour. You may add that after being a rival to Barras for her charms, it would be a shame for him not also to be a rival to the First Consul. That should be enough to help him make up his mind to return, unless he has even more extraordinary liaisons in London.”

Once the door had shut on Dubois and Mahalin, Fouché quickly had an orderly carry the following letter to Doctor Cabanis:

My dear doctor,

The First Consul, whom I have just seen in Madame Bonaparte’s apartments, could not have more graciously received Madame de Sourdis’s request concerning her daughter’s marriage, and he is pleased to see such a marriage take place.

Our dear sister can therefore plan her visit to Madame Bonaparte, and the sooner the better.

Please believe me your sincere friend,

J. Fouché

The next day, Madame la Comtesse de Sourdis presented herself in the Tuileries. She found Josephine radiant and Hortense in tears, for Hortense’s marriage with Louis Bonaparte was almost certain.

Josephine had realized the day before that, whatever mysterious reason lay behind it, her husband was in good humor, so she had asked to have him come see her on his return from the Conseil d’Etat.

But, when he got back, the First Consul had found Cambacérès waiting for him—he’d come to explain two or three articles of the code that Bonaparte had found to be not sufficiently clear—and the two of them had worked until quite late. Then Junot had shown up to announce his marriage with Mademoiselle de Permon.

News of this marriage pleased the First Consul far less than the one arranged for Mademoiselle de Sourdis. First of all, Bonaparte had himself been in love with Madame de Permon; in fact, before marrying Josephine, he had tried to marry her. But Madame de Permon had refused, and he still held a grudge. Furthermore, he had advised Junot to marry someone rich, and now Junot, on the contrary, was choosing a wife from a ruined family. His future wife, on her mother’s side, was descended from former emperors in the Orient and the girl, whom Junot had familiarly called Loulou, came from the Comnène family as well, but she had a dowry of only twenty-five thousand francs. Bonaparte promised Junot he would add one hundred thousand francs to the basket. Also, as governor of Paris, Junot could be guaranteed a salary of five hundred thousand francs. He would simply have to manage with that.

Josephine had meanwhile waited impatiently for her husband all evening. But he had dined with Junot, and then they had gone out together. Finally, at midnight, he had appeared in his dressing gown and with a scarf over his head, which meant he would not retire to his own rooms until the next morning. Josephine’s face had beamed with joy: Her long wait had been worth it. For it was during such visits that Josephine was able to solidify her power over Bonaparte. Never before had Josephine so insistently pressed her case for the marriage of Hortense to Louis. When he’d gone back up to his own rooms, the First Consul had very nearly agreed to the betrothal of his stepdaughter to his brother.

So, when Madame de Sourdis arrived, Josephine was eager to tell her of her good fortune. Claire was dispatched to console Hortense.

But Claire didn’t even try. She knew only too well how difficult it would have been for her herself to give up Hector. Instead, she wept with Hortense, and encouraged her to bring up the question with the First Consul as he surely loved her too much to consent to her unhappiness.

Suddenly a strange idea came to Hortense: She and Claire, with their mothers’ permission, should consult Mademoiselle Lenormand and have their fortunes told.

It was Mademoiselle de Sourdis who acted as ambassador, presenting to their mothers their wish and asking their permission to put it into execution. The negotiation was long, with Hortense listening at the door and trying to hold back her sobs.

Claire came joyously back. Permission was granted, on the condition that Mademoiselle Louise not leave the presence of the two girls even for a moment. Mademoiselle Louise, as we believe we have pointed out, was Madame Bonaparte’s principal maid, and Madame Bonaparte had complete confidence in her.

Mademoiselle Louise was given strict orders, and she swore on everything that was holy to do her duty. Heavily veiled, the two girls climbed into Madame de Sourdis’s carriage, which was a morning carriage without a coat of arms. The coachman was told to stop at number six, Rue de Tournon; he was not told whom they were going to see.

Mademoiselle Louise was the first to climb down from the carriage. She had her instructions, so she knew that Mademoiselle Lenormand lived in the back of the courtyard and to the left. She would then lead the girls up three steps and knock on the door to the right.

She knocked, and when she asked to come in, she and the two girls were led into a study off to one side, not generally open to the public.

They were informed that each girl would be received separately, because Mademoiselle Lenormand never worked with more than one person at the same time. The order in which they would be received would be determined by the first letter of their family name. Thus Hortense Bonaparte would be first. Still, she had to wait a half hour.

The arrangement greatly upset Mademoiselle Louise, for she had been ordered never to let the girls out of her sight. If she remained with Claire, she’d lose sight of Hortense. If she accompanied Hortense, she’d lose sight of Claire.

They took the question to Mademoiselle Lenormand, who found a way to reconcile the situation. Mademoiselle Louise would remain with Claire, but Mademoiselle Lenormand would leave the door of the study open so that the maid would be able to keep her eyes on Hortense. At the same time, she would be far enough away from Mademoiselle Lenormand that she would not be able to hear what the prophetess was saying.

Naturally, both girls had requested the grand set of cards. What Mademoiselle Lenormand saw in the cards for Hortense seemed to impress her greatly. Her gestures and facial expressions indicated growing astonishment. Finally, after she had again shuffled the cards well and carefully studied the girl’s palm, she stood up and spoke like one inspired. She pronounced just one sentence, which brought an incredulous expression to her subject’s face. In the face of Hortense’s pressing questions, she remained mute and refused to add a single word to her declaration, except to say: “The oracle has spoken; believe the oracle!”

The oracle signaled to Hortense that her time was up and summoned her friend.

Although it was Mademoiselle de Beauharnais who had proposed coming to consult Mademoiselle Lenormand, Claire, after what she had seen, was equally eager to learn her future. She hurried into the prophetess’s study. She had no idea that her future would astonish Mademoiselle Lenormand as much as had her friend’s.

With the confidence of a woman who believed in herself and hesitated to offer improbable utterances, Mademoiselle Lenormand read Claire’s cards three times. She studied Claire’s right hand, then the left, and in both palms she found a broken heart, the luck line cutting through the heart line and forking toward Saturn. In the same solemn tone she had assumed in her pronouncement for Mademoiselle de Beauharnais, she spoke her oracle for Mademoiselle de Sourdis. When Claire rejoined Mademoiselle Louise and Hortense, she was as pale as a corpse, and her eyes were filled with tears.

The two girls did not say one word further, did not ask a single question, so long as they were under Mademoiselle Lenormand’s roof. It was as if they feared that any utterance on their part might bring the house down around their heads. But, as soon as they were settled in the carriage and the coachman had started the horses off at a gallop, they both asked at the same time: “What did she tell you?”

Hortense, the first to be received, was the first to answer. “She said: ‘Wife of a king and mother of an emperor, you will die in exile.’”

“And what did she tell you?” Mademoiselle de Beauharnais asked eagerly.

“She said: ‘For fourteen years you will be the widow of a man who is still alive, and the rest of your life the wife of a dead man!’”