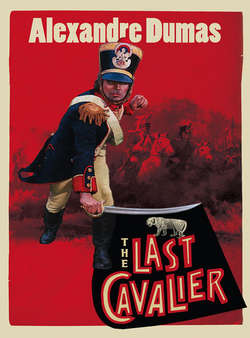

Читать книгу The Last Cavalier: Being the Adventures of Count Sainte-Hermine in the Age of Napoleon - Александр Дюма, Alexandre Dumas - Страница 29

XXV The Duc d’Enghien [I]

ОглавлениеMONSIEUR LE DUC D’ENGHIEN LIVED in the little Ettenheim chateau, on the right bank of the Rhine about twenty kilometers from Strasbourg in the Grand-Duchy of Baden. He was the grandson of the Prince de Condé, who was himself the son of the one-eyed Prince de Condé who cost France so dearly during the regency of Monsieur le Duc d’Orléans. Just one Condé, and he died young, separated the one-eyed duke from the Condé whose victories at Thionville and in the Battle of Nördlingen won him the name The Great Condé. His great greed, rotten morals, and cold cruelty proved him indeed to be the son of his father, Henri II de Bourbon. Condé’s strong desire to occupy the French throne prompted him to disclose that Anne d’Autriche’s two sons, Louis XIV and the Duc d’Orléans, were not in fact the sons of Louis XIII, which could easily have been true.

It was with Henri II de Bourbon that the celebrated Condé family changed character. No longer generous, it became greedy; no longer gay, it became melancholic. Although history states that he was the son of Henri I de Bourbon, Prince de Condé, chronicles from that time protest against the filiation and assign him a quite different father. Apparently Henri I’s wife, the duchess Charlotte de la Trémouille, had been living in adultery with a Gascon page when suddenly, after a four-month absence, her husband returned home with no warning. The duchess quickly made a grim decision; after all, an adulterous woman is already halfway down the road to a murder. She afforded her husband a royal welcome. Although it was wintertime, she managed to find some lovely fruits, and with him she shared the most beautiful pear in the basket. The knife she used to cut the pear had a golden blade, and one side of it had been bathed with poison. The prince died that very night.

Charles de Bourbon reported the news of the death to Henri IV, and attributed the cause to papal decree: “His death was caused by Pope Sixtus V’s excommunication,” he said. “Yes,” Henri IV replied, never one to pass up an opportunity to be witty, “the excommunication didn’t hurt, but something else lent a hand.”

An investigation was opened, and serious charges were leveled against Charlotte de Trémouille. Henri IV asked that all the trial documents be delivered to him, and then threw every bit of them into the fire. When he was asked the reasons for his unusual action, he replied simply, “It is better for a bastard to inherit the Condé name than for such a great name to disappear forever.”

So a bastard did inherit the Condé name, and he brought into that parasitic branch of the once noble family vices that had rather go unnamed. Rebellion, certainly, was the least of them.

Our position is different from that of other novelists. If we fail to report such details, we are accused of not knowing history any better than some historians. And if we do reveal them, then we are accused of trying to sully the reputation of the royal families.

But let us hasten to add that the young prince Louis-Antoine Henri de Bourbon had none of the failings of his father, Henri II de Bourbon, who, had he not been imprisoned for three years, would never have come back to his wife, though she was the most beautiful creature of the time. And none of the failings of the Great Condé, whose amorous relationship with Madame de Longueville, his sister, were the talk of Paris during the Fronde; or of Louis de Condé, who, while he was regent of France, simply emptied the state’s coffers into his own and those of Madame de Prie.

No, the young prince Louis-Antoine was a fine-looking young man of thirty-three years. He had emigrated with his father and the Comte d’Artois, and in ’92 he had joined the corps of émigrés that had gathered along the Rhine. For eight years he had been at war against France, it is true, but he fought in order to combat principles that his princely education and royal bias forbade him to support. When Condé’s army was disbanded, as it was after the Lunéville peace treaty, the Duc d’Enghien could have moved to England, as had his father, his grandfather, other princes, and most of the émigrés. But because of a love affair no one knew about then, although it has become common knowledge since, he chose to set up residence, as we have said, in Ettenheim.

There he lived like an ordinary citizen. The immense Condé fortune, which had been built with gifts from Henri IV, the possessions of the Duc de Montmorency (who was decapitated), and the plunders of Louis le Borgne, had all been confiscated by the Revolution. The émigrés living around Offenburg often came to pay their respects. Sometimes the young men would organize large hunting parties in the Black Forest. At other times the prince would disappear for six or eight days, then reappear suddenly, without anyone knowing where he had been. His absences elicited all sorts of conjectures, and with neither confirmation nor denial, he simply let people think and say whatever they wanted to, no matter how strange their speculations and no matter the cost to his reputation.

One morning, a stranger came to Ettenheim. He had crossed the Rhine at Kehl, then followed the Offenburg road, and finally presented himself at the prince’s door. The prince had been gone for three days.

The stranger waited. On the fifth day, the prince returned home. The stranger told the prince his name and the name of the man who had sent him. He asked that he be received at such time that the prince found it to be convenient. The prince invited the stranger in straightaway.

Sol de Grisolles was the stranger’s name.

“You have been sent by the good Cadoudal?” the prince asked. “I just read in an English newspaper that he had left London and returned to France to avenge an insult made to his honor, and that once the insult had been avenged, he had gone back to London.”

Cadoudal’s aide-de-camp recounted the adventure as it had happened, without omitting a single detail. He told the prince, too, that he’d been sent to the First Consul to declare the vendetta. Then he spoke of his mission to Laurent, whom he had ordered, in Cadoudal’s name, to call the Companions of Jehu back to the work they had been doing before Cadoudal had relieved them of their duties.

“Have you nothing more to tell me?” the young prince asked.

“Yes, I do, Prince,” said the messenger. “I need to tell you that in spite of the Lunéville peace agreement, war will break out with renewed ferocity against the First Consul. Pichegru has finally come to an understanding with your father, and he will join in the cause with all the hate that’s been kindled by his exile in Sinnary. Moreau is furious at how little recognition his victory at Hohenlinden has received, and he is tired of seeing the Rhine army and its generals sacrificed for the troops in Italy. So he too is ready to place his forces and his immense popularity behind a rebellion. And there is more. There is something almost nobody knows anything about, and I am to reveal it to you, Prince.”

“What is that?”

“Within the army a secret society is being established.”

“The Philadelphian Society.”

“Are you familiar with it?”

“I have heard about it.”

“Does Your Highness know who its leader is?”

“Colonel Oudet.”

“Have you ever seen him?”

“Once in Strasbourg, but he did not realize who I was.”

“What does Your Highness think of him?

“He seemed to me to be a bit young and a little frivolous for the huge undertaking he has dreamed up.”

“Yes, Your Highness is not mistaken,” said Sol de Grisolles. “Still, Oudet was born in the Jura mountains, and he has all the physical and moral strength of mountain people.”

“He’s barely twenty-five years old.”

“Bonaparte was only twenty-six when he undertook his Italian campaign.”

“He started out as one of ours.”

“Yes, and we first met him in the Vendée.”

“And then he went over to the Republicans.”

“Which is to say he grew tired of fighting against Frenchmen.”

The prince gave a sigh. “Ah! I too,” he said, “am tired of fighting Frenchmen.”

“Never—and may Your Highness accept the opinion of a man who is not quick to praise—never have such natural and such contrasting qualities been united in one man as they are in this Oudet. He is as naïve as a child, brave as a lion, giddy as a girl, and as tough as an old Roman. He is active and relaxed, lazy and relentless, changeable in mood and unchanging in his resolutions, sweet and strict, tender and terrible. I can add only one more thing in his honor, Prince: Men such as Moreau and Malet have accepted him as their leader and have promised to obey him.”

“So, at the present time the three leaders of the society are.…”

“Oudet, Malet, and Moreau. Philopœmen, Marius, and Fabius. A fourth will join them, Pichegru, and he will take the name Themistocles.”

“I see there are quite diverse elements in this association,” said the prince.

“But very powerful ones. Let us first get rid of Bonaparte, and once his place is empty, then we can worry about the man or the principle that we need to fill it.”

“And how do you intend to get rid of Bonaparte? Not by assassination, I hope?”

“No, but rather in combat.”

“Do you think that Bonaparte will accept a Combat of Thirty?” the prince asked with a smile.

“No, Prince. But we shall force him to accept it. At least three times a week he goes to his country house, La Malmaison, with an escort of forty or fifty men. Cadoudal will attack him with a like number, and God will decide between them.”

“Indeed, that is combat and not assassination,” said the prince thoughtfully.

“But in order for the plan to be completely successful, Your Highness, we need the assistance of a French prince, a brave, popular French prince such as you. The Dukes of Berry and Angoulême, as well as your father and the Comte d’Artois, have made and broken so many promises that we can no longer count on them. So I’ve come to tell you, Milord, that all we are asking for is your presence in Paris, so that when Bonaparte is dead the people will be drawn back to royalty by a true prince from the House of Bourbon, one who is able and eligible to occupy the throne immediately.”

The prince took Sol de Grisolles’s hand. “Monsieur,” he said, “I thank you from the depths of my heart for both your and your friends’ esteem. I shall give you, to you personally, some warrant for that esteem, perhaps, by divulging to you a secret that nobody knows, not even my father.

“But to the brave Cadoudal, to Oudet, Moreau, Pichegru, and Malet, this is my response: ‘For nine years I have continued the campaign. For nine years, I swear by my life, which I risk daily and which is unimportant, I have been filled with disgust and contempt for those powers who call themselves our allies and use us only as instruments. Those powers have made peace, yet they did not deign to include us in their treaty. All the better. Alone now, I will not perpetuate a parricidal war, like the war in which my ancestor the Great Condé drowned part of his glory. You will tell me that the Great Condé was waging war against his king, and I against France. From the point of view of these new Republican principles that I am fighting against, and on which I can personally make no pronouncement, my ancestor’s excuse could rightly have been that he was fighting against nothing more than a king. I have fought against France, yes, but as a minor figure. I never declared war, nor did I bring it to an end. I left everything to destiny. To fate I answered: “You have summoned me; here I am.” But now that peace has been made, I will do nothing to change what has been done.’ That’s what you will tell my friends.

“And now,” he added, “this is for you, but for you alone, monsieur. And please assure me that the secret I’m about to confide in you will never leave your breast.”

“I so swear, my lord.”

“Well, and please forgive my weakness, monsieur: I am in love.” The messenger drew back.

“Weakness, yes,” the duke repeated, “but happiness at the same time. A weakness for which I risk my neck three or four times a month by crossing the Rhine to see an adorable woman, a woman whom I love. People think an estrangement from my cousins and father is keeping me in Germany. No, monsieur. What is keeping me here in Germany is my love, my burning, superlative, invincible love, which is more important to me than my duty. People wonder where I go, they wonder where I am, they think I’m conspiring. Alas! Alas! I am in love, and that is all!”

“Love is a grand and sacred thing when it can make a Bourbon forget even his duty,” Grisolles murmured with a smile. “Do not forsake your love, my prince. And may you be happy! That, you may be sure, is man’s true destiny.” Grisolles rose to his feet to take leave of the prince.

“Oh,” said the duke, “you cannot leave just like that.”

“Why should I stay?”

“Hear me out a little longer, monsieur. Never before have I spoken to anyone about my love, and my love overwhelms me. I have confided in you, but that is not enough. I want to tell you about it in full. You have stepped into the happy, joyous side of my existence, for she has made it so, and I must describe for you how beautiful she is, how intelligent, how devoted. Please have dinner with me, monsieur, and after dinner, well, then you may leave me, but at least I shall have had the luxury of talking to you about her for two hours. I have been in love with her for three years. Just think of that, and I have never spoken one word to anyone about her.”