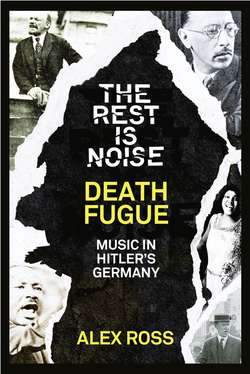

Читать книгу The Rest Is Noise Series: Death Fugue: Music in Hitler’s Germany - Alex Ross - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDEATH FUGUE

Music in Hitler’s Germany

Classical music was one of the few subjects, along with children and dogs, that brought out a certain tenderness in Adolf Hitler. In 1934, when the new leader of Germany appeared at a Wagner commemoration in Leipzig, observers noted that he spoke with “tears in his voice”—a phrase that appears infrequently in Max Domarus’s twenty-three-hundred-page edition of the Führer’s utterances. The previous year Hitler saluted the first Nuremberg Party Congress with a quotation from Wagner’s Meistersinger—“Wach’ auf!” (“Awake!”). Nor was Hitler the only Nazi who expressed reverence for the German musical tradition. Hans Frank, the governor-general of occupied Poland, said that his favorite composers were Bach, Brahms, and Reger. The Berlin Staatskapelle played Siegfried’s Funeral Music at the funeral of SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich, whose father had played in Hans von Bülow’s orchestra and sung major tenor roles at Bayreuth. And Josef Mengele whistled favorite airs as he selected victims for the gas chambers in Auschwitz. There are many such anecdotes about music in the Third Reich, and they reinforce Thomas Mann’s controversial but not easily refuted contention that during Hitler’s reign as dictator of Germany great art was allied with great evil. “Thank God,” Richard Strauss said after Hitler came to power, “finally a Reich Chancellor who is interested in art!”

In the nineteenth century, music, especially German music, was considered a sacred realm sufficient in itself, floating far above the ordinary world. In Nietzsche’s caustic phrase, it became a “telephone from the beyond.” Arthur Schopenhauer claimed in all earnestness that art and life had nothing to do with each other: “Beside the history of the world the history of philosophy, science, and art is guiltless and unstained by blood.” Hans Pfitzner quoted those words as the epigraph to his 1917 opera Palestrina, which celebrated a composer’s ability to rise above the politics of his time. Later, the composer used that same page of his score to write a dedication to Mussolini. That action made nonsense of the claim that music can achieve total autonomy from the society around it. Precisely because of its inarticulate nature, it is all too easily imprinted with ideologies and deployed to political ends.

In the wake of Hitler, classical music suffered not only incalculable physical losses—composers murdered in concentration camps, future talents killed on the beaches of Normandy and on the eastern front, opera houses and concert halls destroyed, émigrés forgotten in foreign lands—but a deeper loss of moral authority. During the war the Allies did their best to rescue the masterpieces of German tradition from Nazi propaganda, reappropriating them as emblems of the struggle against tyranny. The first notes of Beethoven’s Fifth were matched to the Morse code signal for V, as in “Victory.” As the years went by, however, classical music acquired a sinister aura in popular culture. Hollywood, which once had made musicians the fragile heroes of prestige pictures, began to give them a sadistic mien. By the 1970s the juxtaposition of “great music” and barbarism had become a cinematic cliché: in A Clockwork Orange, a young thug fantasizes ultraviolently to the strains of Beethoven’s Ninth, and in Apocalypse Now American soldiers assault a Vietnamese village with the aid of Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries.” Now, when any self-respecting Hollywood archcriminal sets out to enslave mankind, he listens to a little classical music to get in the mood.

The ultimate correlation of music and horror is found in Paul Celan’s 1944–45 poem “Death Fugue,” in which a blue-eyed German instructs death-camp inmates in the art of digging their own graves. As he speaks, he mutates into a conductor urging his violin section to “bow more darkly,” for “death is a Meister from Germany.”

The aftermath of Hitler’s corrosive love of music is unavoidable. Much of subsequent twentieth-century musical history is a struggle to come to terms with it. Although there is no point in trying to restore Schopenhauer’s separation of art and state, it is equally false to claim the opposite, that art can somehow be swallowed up in history or irreparably damaged by it. Music may not be inviolable, but it is infinitely variable, acquiring a new identity in the mind of every new listener. It is always in the world, neither guilty nor innocent, subject to the ever-changing human landscape in which it moves.

“There is too much music in Germany,” Romain Rolland wrote, back in the heyday of Mahler and Strauss. Something was lurking, the French writer suspected, in these humongous Teutonic symphonies and music dramas—a cult of power, a “hypnotism of force.” Germans themselves recognized the demonic strain in their culture. During the First World War, the not yet liberal-Democratic Thomas Mann wrote a manifesto titled Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, in which he praised all the backward German tendencies that he would later come to lament in the pages of Doctor Faustus. In the earlier work, Mann states that art “has a basically undependable, treacherous tendency; its joy in scandalous antireason, its tendency to beauty-creating ‘barbarism,’ cannot be rooted out …”

The melding of German music with reactionary politics goes back to Wagner. The composer’s 1850 pamphlet Das Judentum in der Musik, or Jewry in Music, decried the “Jewification” of German music and de manded that the Jews undergo Untergang and Selbstvernichtung—destruction and self-annihilation.

“Vernichtung” is the word that the Nazis used to describe the mass murder of the European Jews, as Wagner’s most astringent latter-day critics, such as Paul Lawrence Rose and Joachim Köhler, have emphasized. Jens Malte Fischer and other scholars have countered by pointing out that Wagner, in line with Hegel and other German thinkers, conceived “annihilation” not as a physical process but as a spiritual one, akin to Buddhist self-abnegation. Yet, even amid the chorus of nineteenth-century anti-Semitism, Wagner’s rantings stood out for their malicious intensity. The Jews, he once said, were “the born enemy of pure humanity and all that is noble in man.” They were also, he said, the “plastic demon of the ruin of mankind”—a phrase that Joseph Goebbels often employed in his speeches, and that appeared in the foul anti-Semitic film The Eternal Jew.

In Wagner’s waning years, Bayreuth became a mecca for all manner of anti-Semites, Aryan priests, and social Darwinists. The monthly publication Bayreuther Blätter broadcast the racist theories of Paul de Lagarde, Arthur de Gobineau, and, most noxiously, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, who married Wagner’s daughter Eva and became the intellectual leader of Bayreuth after Wagner’s death. Although the composer feared that his disciples would make him look ridiculous, he failed to restrain them. Indeed, he singled out for praise several articles that delivered tendentious racial interpretations of his works.

Inevitably, anti-Semitism seeped into discussion of the music itself. Even in Wagner’s lifetime the jabbering, gesticulating villains in the operas—the dwarves Alberich and Mime and the half-human Hagen in the Ring, the pedant Beckmesser in Meistersinger, the evil magician Klingsor in Parsifal—were sometimes understood as cartoons of Jews. Gustav Mahler believed that Mime embodied the “characteristic traits—petty intelligence and greed” of the Jewish race. “I know of only one Mime,” he added, “and that is myself.” The names of Wagner’s villains could double as code words for Jews. When the right-wing composer Max von Schillings complained in a letter to Strauss that “Alberichs” in the Prussian Culture Ministry were undermining true German art, we can guess that the Jewishness of those agitators, chief among them Leo Kestenberg, prompted the Wagnerian association.

No work by Wagner acquired a more threatening aspect than Parsifal, which the composer created concurrently with his late prose writings on race and regeneration. According to Cosima, he once read aloud from Gobineau’s Essay on the Inequality of Human Races and then went to the piano to play the opera’s Prelude. The plot lends itself all too easily to racial exegesis. King Amfortas is suffering from an obscure wound, which appeared on his body after he succumbed to the mysterious Kundry; he would seem to be the modern German whose blood has mixed with inferior races, thus becoming “Jewified.” Kundry is the female version of the Wandering Jew, who laughed at Christ on His way to the Cross and is now condemned to wander the earth; in a previous life she was Herodias, Salome’s mother. Klingsor prepares to use her again to strike his final blow against the knights. Only Parsifal, the “pure fool,” can resist the advances of Klingsor’s slave. “Verderberin!” he shouts. “Corrupter! Stand away from me! Forever and ever, away from me!”

By remaining pure of blood, Parsifal is able to banish Klingsor, regain the lance that pierced Christ’s side, and preside over the healing of the company of the Grail. As Parsifal holds the spear aloft, Kundry falls dead. Many anti-Semites wished that the Jews themselves could disappear so magically, with a stroke of the Meister’s bow.

Richard Strauss, circa 1933, was the model of the Jewified German. His son, Franz, had married Alice von Grab, the daughter of the Czech-Jewish industrialist Emanuel von Grab. Writers of Jewish ancestry had contributed to almost all of his operas to date: Hedwig Lachmann had made the translation on which Salome was based; Hugo von Hofmannsthal had written the play Elektra and the librettos for Der Rosenkavalier, Ariadne auf Naxos, Die Frau ohne Schatten, Die ägyptische Helena, and Arabella; and Stefan Zweig was by then working on the libretto for Strauss’s next opera, Die schweigsame Frau. Two years later the Propaganda Ministry would note in horror that the vocal score of Die schweigsame Frau displayed the names of no fewer than “4 Juden”: Zweig; the publisher Adolph Fürstner; the composer Felix Wolfes, who made the piano arrangement; and, curiously, the Jacobean playwright Ben Jonson, who wrote Epicoene; or, The Silent Woman, on which the opera was based, and who was not Jewish in the least.

How Strauss became a prize exhibit of Nazi culture is a tangled tale. In his youth he had hardly been a political or cultural reactionary; his first opera, Guntram, unsettled conservative Wagnerians with its anti-collectivist message, and in following years he became Germany’s foremost representative in the marketplace of international modernist decadence. In 1911, Siegfried Wagner, a composer far more modestly talented than his father, bemoaned the fact that Parsifal was being performed in theaters “contaminated by the misfortune-gestating works of Richard Strauss.” The sardonic, anarchic side of Strauss’s character persisted as late as 1921, when he proposed to the critic Alfred Kerr the idea of a “political operetta” set against the chaos of postwar Germany, featuring “workers and industrial councils, prima-donna intrigues, tenor ambitions, resigning directors of the old regime,” together with “the National Assembly, war societies, party politicking while the people starve, pimps as Culture Ministers, criminals as War Ministers, murderers as Justice Ministers,” and, somewhere in the middle, a “true German Romantic” composer who engages in uncouth behavior, flirts with conservatory girls, and, “as a respected anti-Semite, takes donations from rich Jews.” Alas, nothing came of this promising plan.

The Weimar era brought many disappointments. While Krenek’s Jonny and Weill’s Threepenny Opera played to packed houses, Strauss’s artful if sometimes overprecious operatic comedies—Intermezzo, Die ägyptische Helena, Arabella—met with mixed success. By the end of the twenties he had gone a long time without a hit, and insecurities were gnawing at him. Coincidentally or not, his politics slid to the right. When, in 1925, a young journalist named Samuel Wilder—soon to become Billy Wilder, director of Sunset Boulevard and Some Like It Hot—knocked on Strauss’s door to ask his opinion of Mussolini, the composer expressed admiration for the dictator. Strauss met Mussolini more than once, and the two men evidently shared their disgust for artistic modernism. Later in the decade, Count Harry Kessler attended a luncheon at Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s and recorded in his diary that Strauss had spoken in favor of a dictatorship. But the composer had little to say about Hitler himself. The name first crops up in Strauss’s published utterances in November 1932, when, in the wake of the most recent German elections, he matter-of-factly wrote, “Hitler is apparently finished.”

The protagonist of Alfred Döblin’s novel Berlin Alexanderplatz, Franz Biberkopf, is a stubborn, tough-minded, self-reliant man who finds himself transformed into a Nazi stooge. In much the same way, Strauss’s philosophy of self—“The laws of my mind determine my life,” to quote Guntram—left him defenseless before Hitler’s seductions. Nazism was itself the product of egoism, nihilism, cynicism, and amoral aestheticism. Hitler relished the role of the munificent prince: he displayed avid interest, made knowledgeable comments, behaved bashfully around his favorites. That the master of Germany should have assumed a servile air in Strauss’s presence was thoroughly flattering. The two men first talked at length at the Bayreuth festival of 1933, when Strauss stepped in to conduct Parsifal after Toscanini had withdrawn in protest. The composer mentioned various matters that concerned him, including the idea of using film and radio revenues to support theater. He also put in a good word for the Jewish conductor Leo Blech. “I thank you,” Hitler said simply.

Certain of Hitler’s defining musical experiences took place against the familiar backdrop of Austria in the spring of 1906. He made his first trip to Vienna at the beginning of May, venturing forth from his hometown of Linz. On May 7 he sent his friend August Kubizek a postcard mentioning that he would see Tristan at the Court Opera the following night and The Flying Dutchman the night after. In a second card he gave his impression of the acoustics: “Powerful waves of sound flood the room, and the murmur of the wind gives way to a terrible frenzy of surging sound.” The third card said: “Today 7:30–12 Tristan.” Hitler stayed in Vienna for several more weeks, and he would have had time to go see Salome in Graz. Manfred Blumauer, the only scholar who has thoroughly investigated the matter, leaves open the unanswerable question of whether or not Hitler actually made the trip. Either way, he did tell Franz and Alice Strauss, in 1933 or 1934, that he had attended the Graz performance. Alice recounted the conversation to Blumauer decades later. At this meeting or another like it, Hitler apparently kissed Alice’s hand, despite the fact that she was Jewish.

The Tristan that Hitler saw in Vienna in 1906 was the famous production that originated under Gustav Mahler. Alfred Roller, the painter and stage designer, used a semi-abstract, Symbolist interplay of color and light to heighten the mysteries of Wagner’s score. Riveted by the spectacle, Hitler formed the ambition of studying painting and opera direction under Roller. He managed to obtain a letter of introduction from his mother’s landlady, who had connections in Vienna. But when he moved to the imperial city, in February 1908, he failed to follow up on the invitation, even though Roller had spelled out where and when he could be found. Hitler later claimed that he had gone up to Roller’s door before turning away in a state of anxiety. Images of Tristan stayed with him: in a sketchbook from the period 1925–26 he reproduced the image of the lovers huddled under a canopy of stars, and in 1934, when he finally met Roller, he could still recall the production in detail, including “the tower to the left with the pale light.”

Biographies of Hitler have generally overlooked the fact that the conductor of Tristan on May 8 was Mahler himself. Kubizek, whose recollections can be used only with caution, states that his friend admired Mahler “because [he] concerned himself with the music dramas of Richard Wagner and produced them with a perfection that for its time literally shone.” The story is partly confirmed by a comment that Hitler made to Goebbels in 1940, to the effect that he “did not contest the abilities and merits” of select Jewish artists such as Mahler and Max Reinhardt.

Hitler had worshipped Wagner from an early age. On various occasions he reported that a performance of Wagner’s Roman drama Rienzi had inspired him to enter politics. In Vienna, Hitler became uneasy over the fact that masterpieces of Aryan culture were being performed in a city thronged with Jews. Once, in conversation with Hans Frank, he recalled hearing Götterdämmerung at the Court Opera and encountering “a couple of yammering Jews in caftans” on his way home. Hitler said: “It’s impossible to think of a more irreconcilable combination. This glorious mystery of the dying hero and this Jewish filth!”

The spectral figure of the ghetto Jew also appears in Mein Kampf. Hitler claims to have met such a person during a long walk and asked himself: “Is this a Jew? … Is this a German?” At that moment, he said, hatred of Jews first welled up in him. There is a strange displacement going on here, given that a Jew occupied the podium during what may have been the most tremendous musical experience of Hitler’s life. Was Mahler a tormenting symbol of Jewish power amid Hitler’s failures? Or did the young man identify with Mahler’s aura, his ability to command forces with a wave of his arms? In photographs, certain of the Führer’s oratorical poses seem vaguely characteristic of Mahler’s conducting—the right hand raised in a clenched, rotated fist, the left hand drawing back in a clawlike motion.

Hitler made his political reputation by bellowing out bilious speeches in Munich beer halls and soldiers’ barracks, but his knowledge of music helped win him entrée to more rarefied circles. Edwin Bechstein, the renowned piano manufacturer, and Hugo Bruckmann, the publisher who printed the works of Houston Stewart Chamberlain, both welcomed Hitler into their salons. When Hitler met Carl von Schirach, the intendant of the National Theater in Weimar, he launched into a detailed analysis of Die Walküre, comparing recent Weimar performances with legendary ones that he had heard in Vienna. Schirach promptly invited him to tea. Such connections proved crucial in Hitler’s rapid ascent from provincial to national fame.

The Wagner family fell deeply under Hitler’s spell. Winifred Wagner opened the gates of Wahnfried for the man she considered Germany’s savior. Hitler first visited the Wagners on October 1, 1923, as he was preparing his initial attempt at seizing control of Germany. The ailing Chamberlain rose from his sickbed, like Amfortas in Parsifal, to say that Hitler had come to save Germany in its “hour of highest need.” In a later essay Chamberlain called Hitler a true man of the Volk who would rid Germany of the “ruinous, indeed poisonous influence of Jewishness on the life of the German people”—words echoing his own summary of Wagner’s writings on “regeneration.” Hitler was also told that he had a “Parsifal nature.”

Hitler quickly absorbed the Bayreuth lifestyle—vegetarianism, agitation for animal rights, dabblings in Buddhism and Indian lore. Later, he would dote on the younger Wagners and served as a substitute father for the grandsons, Wieland and Wolfgang. When he came to Bayreuth, as he did every summer from 1933 until 1940, he became a different being. “He obviously felt at ease in the Wagner family and free of the compulsion to represent power,” the Nazi architect Albert Speer observed.

The “Beer Hall Putsch” took place on November 8–9, 1923. Siegfried Wagner had planned to commemorate Hitler’s victory by conducting his newest symphonic poem, Glück, at a concert in Munich. Defeat forced him to postpone the premiere, but neither he nor his relations lost faith in the cause. Hitler, confined to Landsberg prison, wrote to express his gratitude. Bayreuth, he said, was “in the line of march to Berlin”; it was the place where “first the Master and then Chamberlain forged the spiritual sword which we are wielding today.” The Wagners kept the prisoner well supplied, sending along recordings of Wagner excerpts, the libretto of Siegfried’s opera Der Schmied von Marienburg, a variety of domestic items (blankets, jackets, stockings, foodstuffs, books), and writing materials, including typing paper of superior quality. A phonograph came from Helene Bechstein. Hitler set to composing Mein Kampf.

Hitler’s speeches of the later 1920s often touched on cultural matters, displaying modest knowledge of the musical scenes of Berlin, Munich, and Vienna. One sign of Germany’s decline, Hitler said, was its growing ignorance of the great musical tradition: “Only a couple hundred thou sand know Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner, only some of them know Bruckner.” Meanwhile, “little Neutöner [new-toners] come and unleash their dissonances.” He made a knowing reference to Krenek’s Jonny spielt auf: “In Germany one lets Jonny strike up and concerning South Tyrol one complains about the Untergang of German culture.” In this same period he criticized the operetta Das Dreimäderlhaus for its travesties of Schubert songs and launched an extended assault on the conductor Bruno Walter, “alias Schlesinger.” In Berlin, Hitler alleged, there were five opera conductors on the staff of the state-funded opera houses, all of them Jews. The reference to “fünf Juden” brings to mind the scene in Salome in which five Jews dispute among themselves in Herod’s court.

Hitler took power in January 1933, and by the end of the year most of the German cultural apparatus had fallen under the control of Goebbels’s Propaganda Ministry. But music did not become a direct instrument of the state. Hitler wanted the ministry to serve the “spiritual development of the nation,” and Goebbels agreed. As the historian Alan Steinweis shows, the minister saw artists as “creating Germans” and organized them into semi-independent organizations. It was called “self-administration under state supervision.” The Reichskulturkammer, or Reich Culture Chamber, had departments for each art form, including a Reich Music Chamber, whose first president was Richard Strauss. Musical life was not merely Nazified from above; to a great extent, it Nazified itself. Even the anti-Jewish clause in the Kulturkammer laws neglected to mention the Jews by name; cultural bureaucrats were left to decide which artists lacked “aptitude” for cultural life. Not surprisingly, all leading Jewish musicians were deemed inept. The April 7, 1933, law barring Jews from the public sector had already had a devastating impact, because so many had been employed by Weimar’s arts programs. Weill left Germany on March 22, Klemperer on April 4, Schoenberg on May 17.

From the start, classical music blared in the background of Nazi life. Party rallies were so immaculately choreographed to Beethoven, Bruckner, and Wagner that the music seemed to have been written in support of the pageantry; it was through such sleights of hand that Hitler generated his authority. Unlike Stalin, who demanded that Soviet art mirror the ideology of the regime, Hitler wished to maintain the illusion of autonomy in the arts. Brigitte Hamann, in her biography of Winifred Wagner, reports that at the Bayreuth festival of 1933 the dictator asked audiences to refrain from singing the “Horst Wessel” song or from making other patriotic manifestations, on the grounds that “there is no more glorious expression of the German spirit than the immortal works of the Master.” Like so many German music lovers, Hitler claimed that the classical tradition was an “absolute art” hovering above history, as in Schopenhauer’s formulation.

Such was the import of Hitler’s most ambitious statement on musical policy, his “cultural address” at the Party rally of 1938, in which he said that “it is totally impossible to express a scientific worldview in musical terms” and “nonsense” to try to express Party business. In contrast to Stalin, Hitler turned up his nose at sycophantic propaganda. In 1935, he directed that no more music should be dedicated to him, and three years later he complained that a group of works commissioned for the Reich Party Day paled in comparison to Bruckner. Politics aspired to the condition of music, not vice versa. Thus, when the Berlin Philharmonic played the finale of Bruckner’s Seventh before that 1938 speech, the implication was that Hitler’s rhetoric would follow the musical model. Goebbels wanted his propaganda efforts to stress, in Wagnerian fashion, key leitmotifs, renewed through ingenious variations.