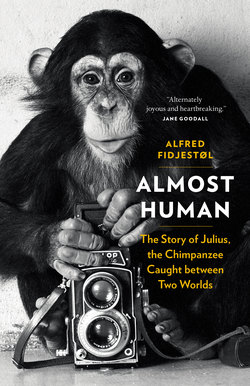

Читать книгу Almost Human - Alfred Fidjestøl - Страница 5

ОглавлениеChapter 1

NATURE AND NURTURE

“Whatever happens happens. We will deal with it later. We can’t just stand here watching the baby die before our eyes.” 1

WILLIAM (BILLY) GLAD

THE HEART is a mysterious muscle. It starts to beat in one moment and then, at some other moment, the beating stops. No one knows the precise reason why a fetus’s heart suddenly starts to beat while in its mother’s womb. No one knows why the first electrical impulse in the heart chamber sends a message to the heart commanding it to contract and, for the first time, pump blood out through tiny, narrow arteries. For a chimpanzee fetus, which gestates in the womb for eight months, the first heartbeat occurs around six weeks. So, the heart of the chimpanzee who is the subject of this book must have felt its very first heartbeat sometime in May of 1979, possibly even on the 17th of May, the Norwegian national holiday, when King Olav stood on the palace balcony in Oslo during a mild spring drizzle and waved down at the annual children’s parade.2 And even today, forty years later, this same heart muscle continues to beat strongly and rhythmically, day in and day out, within the chest of a now fully grown chimpanzee, who resides in a zoo in Kristiansand, in southern Norway.

No one can say exactly when that first heartbeat took place. Observant zookeepers may have taken note that a female chimp named Sanne had failed to ovulate that month. It is simple enough to spot ovulation in female chimpanzees through their pink, swollen genitalia. However, it was only after her cycle failed to appear month after month during the summer of 1979 that Sanne’s pregnancy became clear to the zookeepers. As the birth approached, they did not take any special measures for medical assistance from veterinarians or keepers. The birth of a chimpanzee is less complicated than a human’s. Stillbirth is extremely rare. In the wild, chimpanzees climb a tree when they sense the birth approaching and the laboring mother conducts the entire affair alone. At some point or other during the night between Christmas and December 26, 1979, Sanne gave birth to a small chimpanzee weighing 3.3 pounds. She must have pushed the tiny fetus out unobserved, cleaned it off with nearby pieces of straw and settled down with the newborn, which was still attached by the umbilical cord.

In the morning, keeper Åse Gunn Mosvold arrived on duty. It was a quiet day at the zoo. No visitors had arrived yet and there were few staff members at work. As usual, she first went to the kitchen to put the water on for porridge before checking on the chimps. The chimpanzees were housed inside of the so-called Tropical House for the winter. This enclosure provided them with space to move about in a common area where visitors could view them. There were walls of moss green clay blocks, a steep rock formation surrounded by water, and upright timber beams and green climbing ropes crisscrossing here and there. Behind the scenes, a private sleeping partition was located near the zookeeper kitchen. The chimps were still lounging on the floor inside their sleeping quarters that morning. The group was peaceful and quiet. It was an idyllic scene. Suddenly, Mosvold noticed the reclining Sanne clutching a small chimpanzee baby in her arms, and the umbilical cord that had come loose in the straw. The whole chimp community seemed to quietly accept the new arrival. They paid him scant attention and continued their languid snoozing. “Sanne gave birth in the night! Everything appears to be in excellent condition now, 12:30 p.m. Sanne is lying on the rocks, the baby is on her stomach, high up on her stomach, which is a good sign,” Mosvold noted in the daily observation report for December 26, 1979.3 The tiny chimp had found its way to its mother’s breast and began to feed for the first time.

In its earliest days, the infant chimp didn’t need to do anything other than hold onto its mother. Chimpanzee babies are entirely dependent on their mothers for several years. Humans share this trait with them. A newborn chimp’s fingers or toes will curl around a finger held up against its palms or feet. This is an evolutionary adaptation. Humans share these reflexes with them. We are built to cling to our mothers.

A NEW COMMUNITY

Åse Gunn Mosvold was given the honor of naming the chimp. Seeing as the animal was born during the Christmas season (jul in Norwegian), and she believed it to be a girl, Mosvold dubbed it Juliane. Later, when the chimp was discovered to be male, the name was adapted to Julius.4

The chimpanzee community into which Julius was born was small and relatively new. The Kristiansand Zoo had only recently acquired chimpanzees. Founded in 1965, the zoo was a somewhat haphazard project located in a no man’s land along the E18 highway, almost six miles from the nearest house. Goats, swans, ponies, baboons and brown bears were the largest attractions in the first years. However, Edvard Moseid, the eccentric and animal-loving gardener who became the park’s director in 1967, had greater ambitions. Moseid looked like a hippy, sporting long hair, a mustache and an ever-present cigarette protruding from his lips. But he possessed an otherworldly knack for animals and, as would prove later, a uniquely commercial flair. In 1969, he imported twenty camels from the Moscow Zoo. His plan was to initiate camel breeding and export them to the United States of America. Due to the Cold War, the United States refused to import directly from the Soviet Union. Importing second-generation camels via Kristiansand, however, was completely acceptable. And so for nearly a decade, the exporting of camels became a primary source of income for the zoo. Year after year, the park was expanded and upgraded, new varieties of animals were added and, in 1976, Moseid was finally able to bring in the first generation of the particular species that all self-respecting, ambitious zookeepers dream of—chimpanzees. On January 13, 1976, the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food issued a decision allowing the Kristiansand Zoo to import four chimpanzees from the Jylland Mini Zoo in Herning, Denmark.5 Eight days later, on January 21, 1976, Director Moseid was on board the Danish ferry from Hirtshals to Kristiansand with four chimpanzee passengers in his car. Among them was Sanne, who would later become Julius’s mother. Moseid transported the chimps in individual dog crates, which he then lugged one by one from the car up to his berth. It was a night crossing and there were strong winds and towering waves. All four chimpanzees got seasick and vomited throughout the entire duration of the trip. After finally arriving at the zoo, they were held in quarantine inside the old camel stalls as required by the Ministry of Agriculture. One of the chimps, which turned out to be sick and unsuitable for public presentation, was shipped back. Another had to be put down a year later on suspicion of tuberculosis. The only two remaining chimps were Sanne and a small male named Polle. For this reason, the zoo requested permission from the Ministry of Agriculture in March of 1977 to import two additional adult chimpanzees from the Borås Zoo in Sweden, a male and a female, named Dennis and Lotta. They were ten and nine years old, respectively, when they arrived by car to Kristiansand. With the arrival of Dennis, the community had acquired a potential alpha chimp. Later that same year, two younger female chimpanzees, Skinny and Bølla, were brought in from the Faavang Zoo in Denmark. The Danish zookeeper believed them to be under two years of age, though he couldn’t be certain. Both had been captured in the wild.6

Skinny and Polle both died before Julius was born. A few months earlier, Lotta had given birth to a small male chimpanzee named Billy. Dennis, the alpha male, had become a proud father of two in a very short time. In the first few days, the relationship between Julius and Sanne appeared promising. Sanne was a caring mother. She and Dennis would sit for long periods watching the baby, cuddling and presenting him to one another.7 It was the middle of winter, and they were indoors with little to do. They would lie together and groom each other’s fur, an important activity for chimpanzees, which involves picking out and killing your partner’s lice.

Chimpanzees in captivity have quite a lot of time for this sort of activity. In the wild, chimpanzees spend half of their waking hours either eating or going in search of food.8 They wander about in groups, hunting for food, stopping frequently to overnight in new places, often in the location of their last meal. In these spots, they build small nests high up in the trees where they spend the night. In captivity, there is nowhere to go. The chimps’ every meal is served by humans, though during this early period, Julius was not supposed to receive any other kind of food than his mother’s milk.

The family TV series Norge Rundt (Around Norway), which aired on the NRK station, presented a special feature on the two first chimpanzees born into captivity in Norway. The zoo’s doctor, William (Billy) Glad, after whom the chimp Billy was named, informed viewers that so far Sanne had been a good mother. Sanne had studied Lotta’s childcare regimen during her pregnancy and appeared well prepared, Billy Glad told the Norwegian people during the episode.9

A few weeks later, however, toward the end of January 1980, the keepers began to notice the first signs indicating that Sanne’s behavior toward little Julius wasn’t so rosy after all. Her attitude changed abruptly. She began to put Julius down while she went off to do other things. He was left lying alone for extended periods. It didn’t seem to bother Sanne that he would lie there whimpering. In the jungle, a lone chimp baby would become a quick meal for predators, or even other chimpanzees, if left alone in this way. The father and alpha male, Dennis, was visibly irritated. Every now and then he would go over and nudge the baby, perhaps to send a kind of signal to Sanne to return and resume caring for him.

Sometimes, the younger female chimp, Bølla, would step in as a type of substitute mother, but she did not have breast milk to offer, and the keepers once had to intervene and sedate her in order to remove Julius from her and return him to Sanne—who would then once more act irresponsibly. Sanne’s behavioral shift was odd, resembling postpartum depression. Her keepers noted that she often left Julius to fend for himself for as long as 45 minutes at a time.10

YOUNG MOTHER

Sanne was a young mother, only eight years old. It is not unusual for first-time chimpanzee mothers to be somewhat indifferent to their young. While cats and birds automatically and instinctively know how to care for their offspring, chimpanzees—and humans—must learn these skills from others. It is therefore common for a chimpanzee’s first pregnancy to fail, whether due to miscarriage or stillbirth or the mother’s inability to care for her young. In fact, there is an evolutionary logic to the development in some species of a mechanism in which young mothers do not needlessly waste their time and resources on childrearing until they are socially mature enough to manage the task. It is common in chimpanzee colonies for young mothers to learn about motherhood from the older, more experienced females.11 Often, a chimpanzee mother may allow a young, childless female to try out the role of keeper for her chimpanzee newborn. The mother remains nearby, assuring herself that the young female chimpanzee in training is not taking undue risks, that she is handling the baby gently, that she is not climbing too high with him and that she does leave him lying on his own. Only after such a trial period are the younger female chimps allowed to act as babysitters. Lotta had most likely picked these skills up from other mothers at the Swedish zoo and was thus able to care for Billy, while Sanne had never seen any such behavior modeled at her zoo in Denmark. Although Sanne had been able to observe Lotta’s mothering for a few months, she had apparently not gleaned enough during this short period to give Julius the proper care he needed.

To complicate matters, Sanne was an unpredictable chimpanzee. Her keepers had been curious about how she would handle her role as a mother. Their routines in those days involved considerable risks, as keepers regularly entered the chimpanzee enclosures and came into close physical contact with the chimps. It usually went well enough. The keepers learned to read each individual chimpanzee and decide when it might be safe or unsafe to be in their presence. Dennis was a wise and caring chimp who was easy to figure out. Sanne, on the other hand, was unreliable and her mood could change from one second to the next. She was temperamental and hot-blooded.12

Now that Sanne had a baby it was no longer possible to enter the enclosure with her. It was hard enough trying to get her to change her behavior. The keepers felt helpless to do anything other than stand by, watching Julius from the outside. They tried to isolate Sanne and Julius from the rest of the group in order to encourage better emotional bonding between mother and baby, but even then she would frequently set him aside and continue to ignore him. Julius became dehydrated and overly cold from lying on the cement floor for long stretches of time and could easily have become seriously ill. On February 12, 1980, the situation took a dramatic turn. At some point or another over the course of the afternoon, unobserved, one of the other chimpanzees bit Julius’s finger so hard that his fingertip was hanging loose. None of the keepers knew which chimp was the culprit and some of them believed it must have been Sanne, while others thought it clearly was Dennis’s doing. It may also have been Lotta or Bølla. Only Billy was small enough to be considered innocent in the ordeal. One theory was that Dennis bit Julius in order to evoke a motherly reaction from Sanne or one of the other female chimpanzees.

The wound was discovered around 7:00 p.m. Julius was lying in a pool of blood, howling from the pain. One of the keepers quickly called Billy Glad and director Edvard Moseid, who both arrived as quickly as possible. They were onsite by 7:30 p.m. Julius was on his back, screaming. Edvard signaled that he was going to enter the pen to help Julius, but Sanne responded with a clear gesture indicating that he was not allowed. Instead, she scooped Julius up but held him carelessly and roughly at an arm’s distance, away from her own body. After a short while she put him back down again, this time on his stomach in the hay. Julius appeared starved; he grew silent and seemed nearly dead. Sanne was more concerned with the three humans than with her baby’s well-being. Julius was going to die if Edvard and Billy did not intervene. They felt they had no choice. They had to try to save him. “Whatever happens, happens. We will deal with it later. We can’t just stand here watching the baby die before our eyes,” Billy noted in his journal.13

Sanne flew into a rage as they came close; she did not want to let them into the enclosure. Her maternal instinct was still functioning in this single aspect. Although she ignored Julius, she now acted to protect him from intruders. Edvard tried pulling Julius out with a plastic rake, but Sanne’s brutal reaction stopped him. Nor could they persuade Sanne to go into a separate pen so they enter and retrieve Julius. They tried tempting her with grapes and bananas, even with soda, but Sanne wouldn’t budge. Time was running out. They had to get ahold of the chimpanzee baby. Thinking they might already be too late, they decided to fetch a hose. Billy aimed the powerful jet of water straight at Sanne, pressing her toward the back wall as Edvard opened the feeding hatch, leaned in with the rake and scooped Julius toward the fence where it was possible to coax the tiny creature under it and out of the enclosure.14

It was 8:15 p.m. when Billy finally held Julius in his arms. Julius smelled bad and was dirty, his fingertip dangled loosely with a bone sticking out. Billy wrapped him inside of a blue wool sweater and a military jacket while Edvard sprinted down to the office to call Billy’s wife, Reidun. He informed her that a party was on its way to their house in Bliksheia with a small baby chimpanzee.

“That’s fine,” she replied.15 They administered a few teaspoons of sugary water to Julius before carrying him down to the parking lot where they stowed him in the front seat of Billy’s car and drove home to the Glad family. Here Julius would remain for a few days until his health improved and his finger healed. No one knew what would happen after that. There was no plan. From here on out, it was all improvisation.