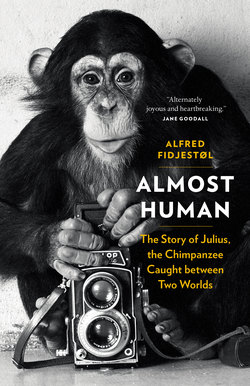

Читать книгу Almost Human - Alfred Fidjestøl - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter 3

A ROOM OF ONE’S OWN

“A chimpanzee kept in solitude is not a real chimpanzee at all.” 48

WOLFGANG KÖHLER

DURING JULIUS’S EARLY life, most of our knowledge about wild chimpanzees came from a single human: the British researcher Jane Goodall. Since childhood, Goodall had dreamed of moving to Africa and living among the chimpanzees. She chanced upon just such an opportunity in adulthood when a former schoolmate moved to a farm in Kenya and invited Jane to visit. Once in Kenya, Jane first landed a job as a secretary in Nairobi. However, her interest in chimpanzees eventually led her to cross paths with National Museum paleontologist and anthropologist, Louis Leakey. He was so impressed with the self-taught Jane Goodall that he soon hired her as his own secretary. Leakey allowed Jane to accompany him as he searched for the fossils of prehistoric human species while at the same time putting her skills as a field worker to the test. He was persuaded by what he saw and suggested that Goodall carry out a pioneering study in Tanzania following the wild chimpanzees in the Gombe National Park on Lake Tanganyika over a long period. Her work would provide the research community with the first ever glimpse into the daily lives of wild chimpanzees. The fact that Goodall was self-taught and unschooled on the subject was more of a boon than a disadvantage, Leakey believed. He would secure financial funding, but she would have to find a partner to join her endeavors. On July 16, 1960, Goodall left for a four-month-long research trip together with her mother, Vanna, and a local cook named Dominic.49

The project was both audacious and naïve. Goodall was twenty-six years old, inexperienced, petite, beautiful and blonde. She intended to go around unprotected with her notebook and binoculars in an area populated by wild chimpanzees, leopards, snakes and buffalos. Several weeks passed before she observed a single thing. Both she and her mother came down with serious cases of malaria. But after three months of fieldwork, she made a groundbreaking discovery as the first human ever to observe the use of tools between wild chimpanzees. Leakey had been searching for just such a breakthrough and had explained to her beforehand that an observation like this would justify the entire project. For the first time, Goodall observed and described the manner in which the chimpanzees selected sticks, modified them by removing leaves and adjoining twigs and then proceeded to use them to fish termites out of hollow tree stumps—in other words, the chimps created and used tools. The implications were far-reaching, not only for how one viewed chimpanzees, but also for the very definition of what it means to be human: “Now we must redefine tool, redefine Man, or accept chimpanzees as humans,” Leakey responded by telegraph after receiving news of the discovery.50 Up until then, humans had been defined as the only creature to use tools, a tone set by the 1949 Kenneth Oakley classic, Man the Tool-Maker. From now on, what it meant to be human would have to be redefined. Goodall’s breakthrough led to renewed funding and an extended period of research work in the field.

After the chimpanzees realized that the strange white female primate with binoculars was no threat to them, Jane Goodall was slowly able to come into closer quarters with them. She began recognizing each one individually and gave them names. She learned to decode the various forms of body language between the chimpanzees, many of them strikingly similar to human gestures such as kissing and embracing, holding hands or patting one another on the shoulder for encouragement. She discovered several ways in which the chimpanzees used tools, such as their tendency to pick leaves and then proceed to chew and crumple them up so that they would become soft and absorbent and useful as sponges to retrieve water from difficult-to-reach holes in tree trunks. Or how they would crack nuts with an assortment of objects, or use leaves to clean themselves off when dirty. The male chimpanzees, in particular, would wash away their semen directly after mating. Goodall eventually got so close to the chimpanzees that she was allowed to touch them, to stroke and groom their fur and to feed them from her hand. Of course, this was extremely risky behavior—the chimpanzees were also at risk of catching contagious diseases to which they were not immune—but Goodall had both faith in God and a solid dose of luck and survived these experiences. She was able to come into closer contact with chimpanzees than any other human before her, in part due to a banana feeding station, which she established in her camp beginning in 1963. This method later received heavy criticism because it influenced and altered the community’s behavior. However, the station made it possible for Goodall to observe how cunning the chimpanzees could be in securing the largest possible number of bananas for themselves. One of the chimpanzees named Figan managed to dupe the others in his group multiple times by pretending to have caught the scent of a promising food source in the forest. He lured the other chimpanzees to investigate the scent with him before abandoning the search party and sneaking back to Goodall’s camp where he knew there would be bananas he could enjoy all to himself.51 In another situation, Goodall set up an experiment in which she placed bananas in boxes that could be opened with a screw and a nut, provided the chimpanzees were able to learn the system. Some of them were successful; others were not. One of the chimps was able to figure out the system quickly and learned to hide his abilities from the others in the group. He would wait until the others were looking in the opposite direction before discreetly opening the box with the screw. After that, he would sit nonchalantly with one hand on the lid without giving off any indication that he had been able to open the lock, all the time waiting until the others would give up and go away so he could eat his bananas in peace.

National Geographic sent the photographer Hugo van Lawick to the Gombe to document the fascinating interplay between the plucky researcher, Goodall, and the wild chimpanzees. The result was a storybook ending. The photographer and Goodall fell in love, married and had a child who was sometimes kept safe in a small cage in the jungle so the chimpanzees wouldn’t kidnap him. In addition, Goodall’s fame grew through a series of magazine reports and her research project became a permanent research center, formally established as the Jane Goodall Institute in 1977. At the center, students and scientists could now follow the lives of individual chimpanzees over decades and generations and thus gather a uniquely vast amount of information about the life cycle of a community of wild chimpanzees. Among other studies, these researchers have followed thirteen young chimpanzees that had experienced, like Julius, separation from their mothers at a young age. The researchers were able to monitor these chimps until adulthood to observe the course of their lives and well-being. Most of these chimpanzees experienced what Goodall labeled “clinical depression,” displaying signs of apathy and a notably low frequency of mating. Some of them died because they were not able to take care of themselves without their mothers. Others experienced long-lasting changes in behavior, while still others adjusted to normal chimpanzee behavior after a while.

Edvard Moseid and Billy Glad, who had both read everything Jane Goodall had written, hoped that Julius would land in this last category. Thus far, there was nothing to indicate that Julius suffered from any form of depression. At the same time, it was very unclear what now needed to happen in order to return him to his mother and the rest of the chimpanzee group at the zoo. Many of the zoo staff thought it completely unrealistic to return Julius back to his community. They believed Moseid and Glad were refusing to see reality because they were blinded by their feelings for the small animal. Of course, the skeptics were right.

THE CAGE PROCEDURE

The pain in Edvard Moseid’s finger did not let up after Dennis’s brutal attack. On August 29, 1980, Moseid was once again taken to the West Agder Central Hospital, and Julius was sent back to the Glad family for a few days. Now that Julius had grown, he was able to join in more advanced forms of play with the Glad sons, Carl Christian and Øystein. They had a cowboy-themed Playmobil setup, complete with a sheriff, saloon, horses and people figures that they would set up on the floor, improvising the figures’ movements and dialogue. Julius, who had a tendency to clamber through the buildings and people, toppling the whole setup, earned the name “King-Kong.”52

Glad worried that Julius was inspired by the two children to walk around on his hind legs. And he realized that Julius was being raised much more freely than Billy, the other young zoo chimpanzee. Billy would never dream of eating a banana or apple until he had looked at his mother Lotta and received a confirming glance that it was all right. It was hard to imagine Julius adapting to these kinds of social graces once he rejoined the chimpanzee group. At the same time, it was difficult to figure out how the chimpanzee mothers were able to extract such obedience and discipline from their young. Marit Moseid would often stand by, watching the interaction between Lotta and Billy in the hopes of learning the key to such motherly behavior so she might implement it with Julius. But she was unable to crack the code.53

Edvard Moseid and Billy Glad agreed that, from here on out, they would all need to be stricter with Julius and ensure that he only ran around on four legs. In order to set boundaries for Julius, they decided to experiment with a method of biting him on the neck and arms when necessary. They tried to bite somewhat strongly with the knowledge that he would have to get used to the strong bites of other chimpanzees once he returned to the community. Billy Glad once bit Julius hard enough that he knew his own sons would have screamed in pain from it. Julius, however, simply gave him a playful smile.54

Physically, Julius was developing nicely. At nine months old, he weighed 16.5 pounds, his coat was glossy and clean and smelled good, his teeth were fine and his motor skills impressive—at least as compared to a human child.55 His motor skills were so impressive, in fact, that it was starting to be challenging to have him in a human home. The two families sent him back and forth between their houses. For most of August and all of September, he lived in Vennesla; at the start of October he spent several weeks with the Glads in Bliksheia. Both households did their best to clean up and make repairs when he was away. Julius was now able to climb up and open cupboard doors whenever he liked. He made a mess in the kitchens, discovered paint cans in the Moseid family cellar and spilled paint all over the stairs. Each time before Julius returned, Billy and Reidun Glad tried to limit the potential damage by closing off rooms in the house that they didn’t want ruined, as well as by removing plants and other loose objects in the rooms where he was allowed to roam.

Finally, toward the end of October 1980, a room was set up for Julius at the zoo. That is to say, the entire chimpanzee facility was reorganized so that from here on out, three fixed sleeping areas were designated for the chimpanzees, one of which was reserved for Julius. These quarters were closed to the public. The chimpanzees entered the cages by way of a shutter door that would be opened for them. For as long as Julius was in one of the cages alone, he could not see but only hear and smell the other chimpanzees when they were in the two other cages. The plan was for Julius to spend as much time as possible in this space. In this way, he and the other chimpanzees would gradually get used to one another. The cage was a few square yards in size, with red bars, some straw on the floor and a climbing rope dangling from the top. Julius was allowed to take off his diaper and human clothes as soon as he was in the cage, but one of Edvard Moseid’s jackets was placed inside as a small scent memory from the human world.

Julius would first have to learn to be by himself in the cage. After some time, he then would begin to stay the night. Glad saw this relocation as the definitive milestone in Julius’s reintegration. “If he (and we) are able to carry this off, the chances in respect to his future are relatively positive. If he is not able, then what we have is an enormous problem on our hands, one that can hardly result in anything other than euthanasia,” he reflected.56 However, to pull this off was emotionally challenging. Both of the families were required to let go and gradually lose contact with this being whom they had grown to love. If the so-called cage procedure were to succeed, they would have to be systematic and united in their efforts. They established a “rehabilitation team” consisting of Billy Glad, Edvard Moseid and the two zookeepers, Grete Svendsen and Jakob Kornbrekke. The first time they brought Julius to the cage, he was only to stay for a little while and would be given something to eat inside the cage in order to build positive associations. And in order to contain Dennis’s reactions, they decided to medicate Dennis with Valium whenever Julius was in the cage. It was Dennis they feared more than anything. Julius could not expect any special sort of protection from Dennis just because he was his biological son. Fatherhood is not a significant relationship in the chimpanzee world. As the alpha male, Dennis was primarily responsible for keeping things peaceful and orderly. He could quickly turn violent if Julius were to return to the group and misbehave.

On October 29, 1980, along with Edvard, Julius spent time in the cage for the first time. His reaction to the new surroundings was surprisingly positive. Dennis responded well on the Valium and didn’t show any irritation over his new neighbor, while the other chimpanzees displayed curiosity and interest in Julius. Over the next days, Julius returned with the Moseid girls who played with him inside his cage. But on October 31, he had an accident on his climbing rope. He fell against the bars and hurt one of his front teeth. The tooth was so badly damaged that it had to be pulled. Ørnulf Nandrup, the dentist, came to the zoo on November 6, and Glad set up an improvised operation room in Moseid’s office. Julius was put under anesthesia, and within seven minutes Nandrup had pulled out the entire tooth, which proved to have a much longer root than a human baby tooth. Julius began to wake up fifteen minutes after the operation and only a half hour later was in the Glad family car on his way home to recuperate.57 He was limp and behaved oddly in the car, but after they arrived, he soon calmed down on Reidun’s lap and slept through the entire night.

The next day, however, he was still behaving strangely. He seemed tired, wobbly on his legs, and confused. He was given a bit of Valium and had to take a long nap next to Billy on the bathroom floor. On November 8, he still wasn’t himself and was given more Valium. This recovery period led to a prolonged interruption to the cage procedure, an interruption in which Julius once again got to be human. This might explain why the project got off to a bad start the second time around. Julius was fine as long as there were people nearby, but as soon as he was left alone in the cage, he began to howl and scream. On one day, he was left alone in the cage for six hours, five of them spent screaming. Grete Svendsen was worn out from having to work under such conditions, so the team decided that in the future Julius would be given two daily doses of 5 milligrams of Valium to calm him. His father Dennis was put on a double dose to deal with the stress of having Julius close by.58 Father and son were separated by mesh cages and both were heavily medicated so they could tolerate each other’s presence.

THE FIRST NIGHT IN THE CAGE

The whole process was messy and confusing for Julius. For the time being, he lived in Vennesla in the evenings and overnight, but spent his days in the cage at the zoo. He was a human by night and a chimpanzee by day. For five- and three-year-old Ane and Siv Moseid, it was hard to understand why Julius was being forced to sit alone and afraid in a cage for so many hours a day when it was obvious that he loved being with them. On November 18, Julius became hysterical when he was put into the cage, baring his teeth at Edvard, howling constantly and only stopping when he was taken out again. The cage procedure had reached a complete standstill. The team resolved to be firm and consistent, keeping him in the cage even if he howled, though one of them was allowed to sit inside with him for up to two hours a day in order to ensure his safety.59 And on December 3, 1980, the day—or rather the night—finally came when Julius was scheduled to spend his first night in the cage. Julius gave Edvard his most pitiful look once he realized he was going to be left alone. As Moseid turned off the light and went home for the evening, he could hear Julius’s sobs in the dark cage.60

It was hard for people to drift off to sleep in Vennesla that night. Emotionally, Julius was a kind of younger brother to the Moseid sisters. They couldn’t imagine any other way of categorizing him. And you don’t put your brother into a cage. They were angry with their dad. How could he do something so pointlessly hurtful to someone they loved so much? For Marit Moseid, the process was no less challenging than for her two daughters. After all, she had been the one to carry out the bulk of the daily responsibilities regarding Julius. She and Julius had developed a very close bond, and he was now like a third child in the family. While he had lived at their home, she had changed Julius’s diapers, as she had for both Ane and Siv, bathed all three children, fed them in the evenings, brushed their teeth and put them to bed. And now suddenly, her youngest was sent off to live in a cage. She found it hard to think about it in a professional context. For Edvard Moseid, the zoo director who was frequently required to make tough decisions about various animals, the situation was not quite as awful. But even he didn’t find it easy.

No one knows how Julius fared that night, what time he calmed down, and when he finally fell asleep. When his keepers came in the next morning, they found that he had broken his other front tooth during the night, perhaps from crying with a gaping mouth and then throwing himself against the floor or bars. Nandrup had to be called in again. The operation went well, but Julius continued to harm himself. He bled from his mouth every day, Grete Svendsen noted. Was he deliberately trying to hurt himself? Those on his rehabilitation team speculated whether or not he intended to inflict self-harm.61 They were at a loss. The cage procedure was going so badly that they considered skipping it altogether. Should they jump straight into the next phase: introducing Julius to the community? Such an introduction would be very risky, of course. Dennis was a threat and several of the other chimpanzees appeared to have lost patience with the howling guest next door.

The rehabilitation team voted to introduce Julius to a selected chimp, and chose the five-year-old female, Bølla. She was the right gender and the right age. She was also the one who had previously cared so much for Julius the first time he was rejected by Sanne. The team decided first to test the effects of the calming agent Vallergan on Julius for a few days after which they planned to give Bølla Rohypnol to put her to sleep and then present Julius to the sleeping female.

On December 15, 1980, Bølla was taken out and isolated from the other chimpanzees, but things did not go according to the plan. The original idea was to sedate her through her food but separation from the other chimps made her so angry and uneasy that Bølla refused to eat. Meanwhile, Julius raged inside his cage, howling with his jaw stretched wide and exposing his two missing front teeth. He tried flinging himself against the bars, but Moseid had padded them with plastic to keep him from harming himself. Because Bølla refused to take her sedatives through food, they had to lead her unmedicated into the room alongside Julius’s cage. The veterinarian Gudbrand Hval brought another medication that could be administered through a blowpipe, and the new plan was to sedate her with the blowpipe in the cage. However, she became so remarkably calm in the presence of Julius that both Moseid and Glad were at once struck by the same thought: What if they tried putting both chimps together without sedatives? What would happen if they opened the shutter door, leaving both Julius and Bølla alone together?

They decided to take a chance and opened the shutter. Bølla could now go in to Julius and Julius could go out to Bølla. Edvard’s and Billy’s eyes were fixed on every move. Bølla was the one to finally take initiative. She calmly made her way in to Julius’s cage. He howled, but was much less hysterical than Glad and Moseid had expected. Bølla surprised them and acted gently and curiously rather than being threatening or scary. She reached out to Julius and he quieted down. When Julius once again began to howl, Bølla reacted by being strict, rattling his bed until he became quiet again. Then they both went into the larger cage together. Julius provoked Bølla by assuming a fight position, but Bølla took it as playfulness and did not let herself be drawn in. Billy Glad believed Dennis would instantly have killed Julius for attempting such a stance.

At 2:25 p.m., they touched. For the first time in almost a year, Julius once again had physical contact with a member of his own species. At three o’clock, their play became more heated, so Moseid and Glad decided to separate them. The separation went well. When each of them was in their own cage, the door between them was shut. Bølla was allowed to rejoin the other chimpanzees and was fortunately spared any kind of punishment for being outside of the group with Julius. Julius accompanied Edvard home to Vennesla.

The next day, Bølla and Julius were placed together again, this time for a half hour. In the evening, Glad came to visit Julius after he was back safely in his own cage. Julius was allowed to come out and interact with him and several other keepers before Glad had to return him to his cage. Once inside, Julius sat sucking his thumb and thinking. Glad thought that Julius looked pensive. “Maybe he’s sitting there pondering and starting to understand that he perhaps isn’t a human after all,” Glad speculated that evening.62

Could Glad be right? Could Julius, in fact, be speculating about what he was? Chimpanzees are among the few species of animals with the ability to self-reflect. Studies have shown that most mammals—with the exception of chimpanzees, orangutans and humans—have difficulties in understanding the concept of mirrors. Other mammal species are tempted to try grabbing the individual they see in the mirror, to walk behind the mirror to look for the creature, or they are frightened by the strange “other” animal. The American psychologist Gordon Gallup conducted a clever experiment in the 1970s in which various animals received a mark on their foreheads without realizing it and were thereafter confronted with a mirror. Chimpanzees, orangutans and human children, eighteen months or older, noticed the mark in the mirror. They touched their own foreheads with their hands, trying to understand what it was and to wipe it off; in other words, they understood that the reflections in the mirror were themselves. Other animals and younger children did not grasp the connection. These three species possess a mental capacity that is rare in the animal world, one marked by the ability to be aware of and recognize one’s self.63

There’s nothing particularly surprising about the chimpanzee’s ability to recognize itself in a mirror. The entire social etiquette around which a chimpanzee community is structured is built upon the self-awareness of each member. Each chimp is aware of how the others perceive it and how its own behavior is interpreted by the others, as well as how to behave in order to reach a desired outcome. Chimpanzees display fear by exposing both their upper and lower teeth. In conflict situations in which it is beneficial to appear fearless, researchers have observed chimpanzees’ feverish and mostly futile attempts to hide their fear responses with their hands. Frans de Waal described how, Luit, a male chimpanzee in the Arnhem zoo, pulled his lips together with his hands in order to hide his teeth and fear response from his rival. Luit didn’t succeed at first, though, and was instead overcome by fear, exposing his teeth, but he continued to try pulling his lips together again. Only on his third attempt was he able to discipline his face enough so that he could go out in the open and swagger about like a tough guy in front of his chimpanzee rival.64 A highly developed sense of self-awareness is thus vital to a chimpanzee’s survival. When the chimpanzee Washoe learned to sign in ASL, she was the first chimpanzee in the world to put this self-awareness into words. As she gazed at her own reflection, she was asked “Who that?” and quickly answered the sign for “Me Washoe.”65 In a different experiment Viki, another chimpanzee raised among humans, was given a pile of photographs featuring humans and animals and asked to sort them. She quite correctly separated them into two piles, one of the humans and one of all the animals. She made only one mistake, though not perhaps from her perspective, she placed the photograph of herself into the pile with the human photos.66

No one can say into which pile Julius would have placed himself. It was no easy task for Julius to figure out whether he was animal or human. Up until this point he had been a bit of both; he was almost chimpanzee, almost human.