Читать книгу Naphtalene - Alia Mamdouh - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

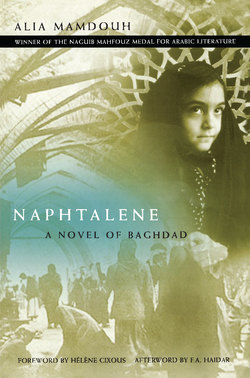

Naphtalene repels moths. But this Naphtalene preserves the remnants, clothing, and memories of two powerful sites of childhood: a little girl and the great city of Baghdad. And this Naphtalene also recalls its chemical origins, its relationship to gasoline and fire, and its links to perfumes, dyes, and odors. This Naphtalene causes the closet in which it is kept and from where it keeps watch to erupt in flaming sentences. What Naphtalene protects is destruction, dislocation, and the pain of love and hate. Naphtalene sings life at its most intense; for here the singer of life’s opera is the most poetic being in the world: a child, and what is more—a child half-boy, half-girl.

Alia Mamdouh’s stunning gesture is to have turned over the keys of the narrative to the violent sensitivities and superior intelligence of childhood. Seen by the untamed, wild, immediate, and uncalculating eyes of a youth, the world appears in monstrous forms, in all its naked extravagances and cruelties, and making no excuses. All the actors are superhuman characters, surging forth from the terraces and public baths of the neighborhood to enter into eternity, smoking and stinking.

Naphtalene is an extraordinary book about Beginnings, a kind of Bildungsroman of Baghdad (a narrative which assembles all the fragments of a prophetic childhood, and which, in remembering the primary elements of subjective life, proposes a vision of the world and an art form). The expression “Bildung,” which speaks of genesis, of formation, and of education, is not, however, sufficient for Naphtalene—for here genesis is also chaos, and apprenticeship is constantly turned upside down, while a wind of revolt blows, shatters, and scatters each scene at the very moment it begins to crystallize. Naphtalene is volcanic; the narration and its narrator are perpetually exploding. Neither family structure, nor institution, nor streets, nor feelings—nothing at all—can resist the fireworks of the naphtha named Huda—genial Huda, devil of society, of the City, and of the novel—a trail of gunpowder. She gives the narration its lightning rhythm: one has never seen a story run so fast, rush so heedlessly toward all its limits, doors and walls, in order to break them open. Huda? In appearance, a girl. In action, a boy. In poetic truth, a fiery daughter.

She is fire, the daughter of an inflamed man, of a mother devoured by tuberculosis.

Fire rules in Naphtalene. The Father, a central character, hated and adored partner of the daughter’s combat with the gods, catches fire at the end of the story as if he had caught his daughter. Fire, masculine and feminine naphtha, never reduced in this text to a banal opposition between sexes or emotions. That’s what is great and free about this work. Love and hate do not oppose each other but mix and blend. In the same way, good attaches to evil and fusion marries effusion. The strong melt, the weak knock the strong to the floor. If the women are slaves and prisoners, the men are the paramount prisoners of the prisons they run.

Freedom? It gushes uncontrollably from the body. It is secretions, odors. A country of odors. Acridities, repulsions, and seductions: everywhere is the penetrating odor of Naphtalene, which kills and bewitches. It is the first version of writing. Freedom? You can’t imprison Voices. Naphtalene is a magnificent hurricane of Voices: the screams of aunts, the chanting of the grandmother’s prayers, the Mother’s coughing, the children’s laughter, the pigeons’ cooing, “the Arab Voices.”

This world is full of Voices: in this, Naphtalene is an enchantment bordering on myth. A marriage of the primordial and of modernity, of fury and of love.

Hélène Cixous

Translated from French by Judith Miller, 2004