Читать книгу Barracoon: The Story of the Last Slave - Alice Walker - Страница 10

ОглавлениеIntroduction

On December 14, 1927, Zora Neale Hurston took the 3:40 p.m. train from Penn Station, New York, to Mobile, to conduct a series of interviews with the last known surviving African of the last American slaver— the Clotilda. His name was Kossola, but he was called Cudjo Lewis. He was held as a slave for five and a half years in Plateau-Magazine Point, Alabama, from 1860 until Union soldiers told him he was free. Kossola lived out the rest of his life in Africatown (Plateau).1 Hurston’s trip south was a continuation of the field trip expedition she had initiated the previous year.

Oluale Kossola had survived capture at the hands of Dahomian warriors, the barracoons at Whydah (Ouidah), and the Middle Passage. He had been enslaved, he had lived through the Civil War and the largely unReconstructed South, and he had endured the rule of Jim Crow. He had experienced the dawn of a new millennium that included World War I and the Great Depression. Within the magnitude of world events swirled the momentous events of Kossola’s own personal world.

Zora Neale Hurston, as a cultural anthropologist, ethnographer, and folklorist, was eager to inquire into his experiences. “I want to know who you are,” she approached Kossola, “and how you came to be a slave; and to what part of Africa do you belong, and how you fared as a slave, and how you have managed as a free man?” Kossola absorbed her every question, then raised a tearful countenance. “Thankee Jesus! Somebody come ast about Cudjo! I want tellee somebody who I is, so maybe dey go in de Afficky soil some day and callee my name and somebody say, ‘Yeah, I know Kossula.’”2

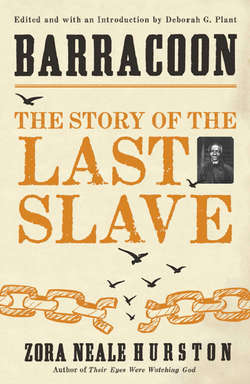

Over a period of three months, Hurston visited with Kossola. She brought Georgia peaches, Virginia hams, late-summer watermelons, and Bee Brand insect powder. The offerings were as much a currency to facilitate their blossoming friendship as a means to encourage Kossola’s reminiscences. Much of his life was “a sequence of separations.”3 Sweet things can be palliative. Kossola trusted Hurston to tell his story and transmit it to the world. Others had interviewed Kossola and had written pieces that focused on him or more generally on the community of survivors at Africatown. But only Zora Neale Hurston conducted extensive interviews that would yield a comprehensive, book-length account of Kossola’s life. She would alternately title the work “Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo’” and “The Life of Kossula.” As with the other interviews, Kossola hoped the story he entrusted to Hurston would reach his people, for whom he was still lonely. The disconnection he experienced was a source of continuous distress.

ORIGINS

Kossola was born circa 1841, in the town of Bantè, the home to the Isha subgroup of the Yoruba people of West Africa. He was the second child of Fondlolu, who was the second of his father’s three wives. His mother named him Kossola, meaning “I do not lose my fruits anymore” or “my children do not die any more.”4 His mother would have four more children after Kossola, and he would have twelve additional siblings from his extended family. Fondlolu’s name identified her as one who had been initiated as an Orìṣà devotee. His father was called Oluale.5 Though his father was not of royal heritage as Olu, which means “king” or “chief,” would imply, Kossola’s grandfather was an officer of the king of their town and had land and livestock.

By age fourteen, Kossola had trained as a soldier, which entailed mastering the skills of hunting, camping, and tracking, and acquiring expertise in shooting arrows and throwing spears. This training prepared him for induction into the secret male society called oro. This society was responsible for the dispensation of justice and the security of the town. The Isha Yoruba of Bantè lived in an agricultural society and were a peaceful people. Thus, the training of young men in the art of warfare was a strategic defense against bellicose nations. At age nineteen, Kossola was undergoing initiation for marriage. But these rites would never be realized. It was 1860, and the world Kossola knew was coming to an abrupt end.

TRANS-ATLANTIC TRAFFICKING

By the mid-nineteenth century, the Atlantic world had already penetrated the African hinterland. And although Britain had abolished the international trafficking of African peoples, or what is typically referred to as “the trans-Atlantic slave trade,” in 1807, and although the United States had followed suit in 1808, European and American ships were still finding their way to ports along the West African coast to conduct what was now deemed “illegitimate trade.” Laws had been passed and treaties had been signed, but half a century later, the deportation of Africans out of Africa and into the Americas continued. France and the United States had joined forces with British efforts to suppress the traffic. However, it was a largely British-led effort, and the US patrols proved to be ambivalent and not infrequently at cross-purposes with the abolitionist agenda.6

Habituated to the lucrative enterprise of trafficking, and encouraged by the relative ease with which they could find buyers for their captives, Africans opposed to ending the traffic persisted in the enterprise. The Fon of Dahomey was foremost among those African peoples who resisted the suppression. Not only was the internal enslavement of their prisoners perceived as essential to their traditions and customs, the external sell of their prisoners afforded their kingdom wealth and political dominance. To maintain a sufficient “slave supply,” the king of Dahomey instigated wars and led raids with the sole purpose of filling the royal stockade.

King Ghezo of Dahomey renounced his 1852 treaty to abolish the traffic and by 1857 had resumed his wars and raids. Reports of his activities had reached the newspapers of Mobile, Alabama. A November 9, 1858, article announced that “the King of Dahomey was driving a brisk trade at Ouidah.”7 This article caught the attention of Timothy Meaher, a “slaveholder” who, like many proslavery Americans, wanted to maintain the trans-Atlantic traffic. In defiance of constitutional law, Meaher decided to import Africans illegally into the country and enslave them. In conspiracy with Meaher, William Foster, who built the Clotilda, outfitted the ship for transport of the “contraband cargo.” In July 1860, he navigated toward the Bight of Benin. After six weeks of surviving storms and avoiding being overtaken by ships patrolling the waters, Foster anchored the Clotilda at the port of Ouidah.

BARRACOON

From 1801 to 1866, an estimated 3,873,600 Africans were exchanged for gold, guns, and other European and American merchandise. Of that number, approximately 444,700 were deported from the Bight of Benin, which was controlled by Dahomey.8 During the period from 1851 to 1860, approximately 22,500 Africans were exported. And of that number, 110 were taken aboard the Clotilda at Ouidah. Kossola was among them—a transaction between Foster and King Glèlè. In 1859, King Ghezo was mortally shot while returning from one of his campaigns. His son Badohun had ascended to the throne. He was called Glèlè, which means “the ferocious Lion of the forest” or “terror in the bush.”9 To avenge his father’s death, as well as to amass sacrificial bodies for certain imminent traditional ceremonies, Glèlè intensified the raiding campaigns. Under the pretext of having been insulted when the king of Bantè refused to yield to Glèlè’s demands for corn and cattle, Glèlè sacked the town.

Kossola described to Hurston the mayhem that ensued in the predawn raid when his townspeople awoke to Dahomey’s female warriors, who slaughtered them in their daze. Those who tried to escape through the eight gates that surrounded the town were beheaded by the male warriors who were posted there. Kossola recalled the horror of seeing decapitated heads hanging about the belts of the warriors, and how on the second day, the warriors stopped the march in order to smoke the heads. Through the clouds of smoke, he missed seeing the heads of his family and townspeople. “It is easy to see how few would have looked on that sight too closely,” wrote a sympathetic Hurston.10

Along with a host of others taken as captives by the Dahomian warriors, the survivors of the Bantè massacre were “yoked by forked sticks and tied in a chain,” then marched to the stockades at Abomey.11 After three days, they were incarcerated in the barracoons at Ouidah, near the Bight of Benin. During the weeks of his existence in the barracoons, Kossola was bewildered and anxious about his fate. Before him was a thunderous and crashing ocean that he had never seen before. Behind him was everything he called home. There in the barracoon, as there in his Alabama home, Kossola was transfixed between two worlds, fully belonging to neither.

KOSSOLA, HURSTON, CHARLOTTE MASON, AND “BARRACOON”

In September 1927, Hurston had met and come under contract with Charlotte Osgood Mason, a patron to several Harlem Renaissance luminaries. Mason funded Hurston’s return to Alabama for the extended interviews with Kossola, and she supported Hurston’s research efforts while preparing Barracoon for publication. In a March 25, 1931, letter to Mason, Hurston writes that the work “is coming along well.” She reported that she had to revise some passages, but that she was “within a few paragraphs of the end of the whole thing. Then for the final typing.” She described the revisions and related her new research findings: “I found at the library an actual account of the raid as Kossula said that it happened. Also the tribe name. It was not on the maps because the entire tribe was wiped out by the Dahomey troops. The king who conquered them preserved carefully the skull of Kossula’s king as a most worthy foe.”12

Hurston and Mason conversed about the potential publication of Barracoon over a period of years. In her desire to see Hurston financially independent, Mason encouraged Hurston to prepare Barracoon, as well as the material that would become Mules and Men, for publication. Charlotte Mason considered herself not only a patron to black writers and artists, but also a guardian of black folklore. She believed it her duty to protect it from those whites who, having “no more interesting things to investigate among themselves,” were grabbing “in every direction material that by right belongs entirely to another race.” Following the suggestions of Mason and Alain Locke, Hurston advised Kossola and his family “to avoid talking with other folklore collectors—white ones, no doubt—who he and Godmother felt ‘should be kept entirely away not only from the project in hand but from this entire movement for the rediscovery of our folk material.’”13

Mason’s support of Hurston’s efforts with Barracoon extended to monetary contributions to Kossola’s welfare. Mason and Kossola would eventually communicate directly with each other, and Kossola would come to consider Mason a “dear friend.” As one letter suggests, Kossola was struggling financially. It had come to Mason’s attention that Kossola had used excerpts from his copy of Hurston’s narrative to gain financial compensation from local newspapers. Kossola dictated a letter to Mason in response to her concern:

Dear friend you may have seen in the papers about my History. But this has been over three years since I has let anyone take it off to copy from it. I only did that so they would help me. But there is no one did for me as you has. The lord will Bless you and will give you a long Life. Where there’s no more parting, yours in Christ. Cudjo Lewis.14

As Mason was protective of Hurston’s professional interests, both women remained concerned about Kossola’s welfare. Having discovered that Kossola was not receiving money that Mason had mailed to him, Hurston looked into the matter. She updated Mason accordingly:

I have written to Claudia Thornton to check up on Kossula and all about things. I have also asked the Post Office at Plateau to check any letters coming to Cudjoe Lewis from New York.15

As Hurston checked on Kossola, she continued revising the manuscript. “Second writing of Kossula all done and about typed,” she wrote Mason on January 12, 1931. On April 18, she was enthusiastic: “At last ‘Barracoon’ is ready for your eyes.”16 Appreciative of Mason’s support, Hurston dedicated the book to her and began submitting it to publishers. In September 1931, she contemplated Viking’s proposal: “The Viking press again asks for the Life of Kossula, but in language rather than dialect. It lies here and I know your mind about that and so I do not answer them except with your tongue.”17 The dialect was a vital and authenticating feature of the narrative. Hurston would not submit to such revision. Perhaps, as Langston Hughes wrote in The Big Sea, the Negro was “no longer in vogue,” and publishers like Boni and Viking were unwilling to take risks on “Negro material” during the Great Depression.18

THE GRIOT

There seems to be a note of disappointment in the historian Sylviane Diouf’s revelation that Hurston submitted Barracoon to various publishers, “but it never found a taker, and has still not been published.”19 Hurston’s manuscript is an invaluable historical document, as Diouf points out, and an extraordinary literary achievement as well, despite the fact that it found no takers during her lifetime. In it, Zora Neale Hurston found a way to produce a written text that maintains the orality of the spoken word. And she did so without imposing herself in the narrative, creating what some scholars classify as orature. Contrary to the literary biographer Robert Hemenway’s dismissal of Barracoon as Hurston’s re-creation of Kossola’s experience, the scholar Lynda Hill writes that “through a deliberate act of suppression, she resists presenting her own point of view in a natural, or naturalistic, way and allows Kossula ‘to tell his story in his own way.’”20

Zora Neale Hurston was not only committed to collecting artifacts of African American folk culture, she was also adamant about their authentic presentation. Even as she rejected the objective-observer stance of Western scientific inquiry for a participant-observer stance, Hurston still incorporated standard features of the ethnographic and folklore-collecting processes within her methodology. Adopting the participant-observer stance is what allowed her to collect folklore “like a new broom.”21 As Hill points out, Hurston was simultaneously working and learning, which meant, ultimately, that she was not just mirroring her mentors, but coming into her own.

Embedded in the narrative of Barracoon are those aspects of ethnography and folklore collecting that reveal Hurston’s methodology and authenticate Kossola’s story as his own, rather than as a fiction of Hurston’s imagination. The story, in the main, is told from Kossola’s first-person point of view. Hurston transcribes Kossola’s story, using his vernacular diction, spelling his words as she hears them pronounced. Sentences follow his syntactical rhythms and maintain his idiomatic expressions and repetitive phrases. Hurston’s methods respect Kossola’s own storytelling sensibility; it is one that is “rooted ‘in African soil.’” “It would be hard to make the case that she entirely invented Kossula’s language and, consequently, his emerging persona,” comments Hill.22 And it would be an equally hard case to make that she created the life events chronicled in Kossola’s story.

Even as Hurston has her own idea about how a story is to be told, Kossola has his. Hurston is initially impatient with Kossola’s talk about his father and grandfather, for instance. But Kossola’s proverbial wisdom adjusts her attitude: “Where is de house where de mouse is de leader?”23

Hurston complained in Dust Tracks on a Road of Kossola’s reticence. Yet her patience in getting his story is quite apparent in the narrative. She is persistent in her returning to his home even when Kossola petulantly sends her away. He doesn’t always talk when she comes, but rather chooses to tend his garden or repair his fence. And sometimes her time with him is spent driving Kossola into town. Sometimes he is lost in his memories.

Recording such moments within the body of the narrative not only structures the overall narrative flow of events but reveals the behavioral patterns of her informant. As Hurston is not just an observer, she fully participates in the process of “helping Kossula to tell his story.” “In writing his story,” says Hill, “Hurston does not romanticize or in any way imply that ideals such as self-fulfillment or fully realized self-expression could emerge from such suffering as Kossula has known. Hurston does not interpret his comments, except when she builds a transition from one interview to the next, in her footnotes, and at the end when she summarizes.”24 The story Hurston gathers is presented in such a way that she, the interlocutor, all but disappears. The narrative space she creates for Kossola’s unburdening is sacred. Rather than insert herself into the narrative as the learned and probing cultural anthropologist, the investigating ethnographer, or the authorial writer, Zora Neale Hurston, in her still listening, assumes the office of a priest. In this space, Oluale Kossola passes his story of epic proportion on to her.

Deborah G. Plant