Читать книгу The Female Gaze - Alicia Malone - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Consequences of Feminism

(Les Résultants du Féminisme)

Gaumont Studio, 1906, France | Black & White, 7 minutes, Comedy

A gender role reversal comedy set in a fictional world where men are the ones being objectified.

Director: Alice Guy

Producer: Gaumont Studios

Cinematography: Unknown

Screenplay: Alice Guy

Starring: Unknown

“There is nothing connected with the staging of a motion picture that a woman cannot do as easily as a man.”

—Alice Guy-Blaché

It is difficult to believe that a film called The Consequences of Feminism was made back in 1906. This is a title which might even be controversial if it were used today. And yet, it exists—a black-and-white silent movie made by the first female director in movie history, set in a world where gender roles have been reversed.

This is apparent from the very first scene in The Consequences of Feminism. The film opens inside a shop where a group of men are occupied with making hats. Suddenly, a woman strides through the door, pointing with her cane at the hat she wants. While waiting, she looks appreciatively at the working men, reaching out to touch the chin of one, who immediately shies away from her hand. After she leaves, another man is tasked with delivering the hat, and he pauses in front of the mirror to apply his makeup. Outside, he is immediately pounced on by a woman who places her hands all over him. He is saved by another woman, who seems kind and gentle as she leads him to a park bench. But before long, she too is forcing herself on him. A couple of women walking by see what is happening and quickly scurry away.

The film continues in this manner for the rest of its seven-minute duration, with later scenes set inside a house and at a women-only establishment. In all cases, the women are clearly in charge, with the men relegated to the positions of workers, housemaids, and caretakers for the children. All the women in this film are pushy, and they objectify, sexually harass, and abuse the men. The men resist as best they can, but eventually give in.

Finally, the men have had enough of their treatment, and they band together to take back their dominant position in society and reestablish the “correct” social order. This is where the true brilliance of this little satire lies. To accept the ending is to admit that half of the world’s population is currently subject to a raw deal.

Nothing has been changed about the appearance of the characters: all the women in the film wear dresses of the period, while the men are in suits. It is only the behavior that is different. Guy has swapped both the power structure of society and the general traits of the genders for comedic effect. The film does not imagine what exactly might happen if we lived in a matriarchal society—that women would sexually harass men—but it shows quite plainly what it is like to live in a patriarchal one.

Of course, we can’t know for sure what statement Guy wanted to make with this film or if her intention was simply to entertain the audience by showing men acting like women. But the title suggests there is more to her vision, that perhaps it is a parody of what people feared would happen if women were to gain more rights. And by showing the men fighting together at the film’s conclusion, Guy seems to be stating why feminism is necessary.

The Consequences of Feminism was made during what we now call the “first wave” of feminism. At the time the use of that word was quite new—“feminism” was only coined in the late 1800s in France, as “féminisme.” Of course, women had been speaking up for themselves long before then, but it was in the 1860s that a more formal movement started to take shape focused on winning the right to vote. By 1906, many filmgoers would have indeed been thinking about the consequences of this new movement.

The premise of the film plays comedically into the fears some people still nurse about feminism—that its true goal is not equality of the sexes (as is the very definition of the term) but that it is instead about waging war on men. This is an irrational fear which supposes that women want to take power away from men to the point where men become the oppressed and women the oppressors.

All of this is the baggage modern audiences inevitably bring to watching The Consequences of Feminism. Viewing this short silent film, it is almost impossible not to think about current conversations about gender and assault. So much is said here without a single piece of dialogue or even a title card being used. It is a movie that was well ahead of its time—and that is ahead of our time, too.

This was also true of the director. Alice Guy was arguably one of the most important figures in the history of cinema. Not only was she the very first female filmmaker, but she was one of the first film directors in the world, whether male or female. And yet few in the industry know her name. Her story is rarely taught in film classes or mentioned in books. And for many decades her work was lost, or incorrectly attributed to male colleagues.

Alice Guy was born in 1873 and started her film career in the late 1800s while working as a secretary at a photography company in Paris, France. Her boss, Léon Gaumont, had been developing a 60mm motion picture camera. He allowed Guy to borrow it on the agreed-upon condition that it wouldn’t interfere with her other work. The first film she made was in 1896, when she was just twenty-three years old. It was a short called The Cabbage Fairy, and was one of the first narrative movies in the world.

From there, her list of achievements is remarkable. She was the first person to direct a movie with synchronized sound, using a Léon Gaumont invention called the Chronophone decades before the mainstream sound revolution would come to pass. She cofounded and ran her own studio, which she called Solax. She made over 1,000 movies over the course of her career while also being a wife and a mother. Her comedies are particularly impressive, with inventive ideas neatly packaged into short-form satire, like very early sketch comedy. Guy also filmed dance sequences, dramas, and even a religious epic called The Life of Christ in 1906. This was one of the most ambitious productions in cinema at the time, involving a staggering 300 extras.

With all her experimentation, Alice Guy helped to form the basis of film grammar and structure. She encouraged her actors toward a more modern style, asking them to “be natural” instead of posing and posturing to the camera.

In 1912, using her married name of Alice Guy-Blaché, she made another comedy where the gender roles were reversed. In the Year 2000 feels like a remake of The Consequences of Feminism, with the difference that this time it is the women who win in the end. On its release in 1912, the magazine Moving Picture World wrote about In the Year 2000, saying:

“A great number of prognostications often terrify us with visions [of] what will be when women shall rule the earth and the time when men shall be subordinates and adjuncts. It is rather a fine question to decide—for chivalrous men, anyway. Today with the multiplicity of feminine activities and the constant broadening of feminine spheres, it’s difficult to predict what heights women will achieve… Women in this film are supreme, and man’s destiny is presided over by woman. No attempt is made at burlesque—but the very seriousness of the purpose makes the situations ludicrous.”

Alice Guy-Blaché was awarded the Legion of Honor in 1953 and died in 1968 at the age of ninety-four. Around 130 of her 1,000 films remain, with much work being done to restore and preserve her important place in history.

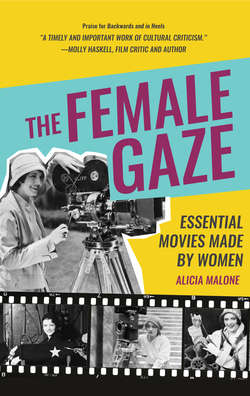

THE FEMALE GAZE

Alice Guy uses the device of gender role reversal to make her audience think about how women are treated in the real world and how ludicrous it is to believe that women would act exactly like men if they were given more power.

FAST FACTS

★Alice Guy played a vital role in the development of cinema

and worked in both France and the US during the birth of the film industry.

★Guy married fellow Gaumont Studios employee Herbert Blaché in 1907. Shortly after their wedding, the two moved to the US, where Guy set up Solax Studios.

★After her divorce, Guy returned to France in the 1920s, but she found it impossible to get work as a film director.

★In the early 1900s, film wasn’t thought to be an important art form. Many silent films were destroyed and accurate archives weren’t kept. The achievements of early filmmakers such as Alice Guy remained largely hidden until the work of film historians such as Anthony Slide. He wrote about Guy in his book Early Women Directors, published in 1977, and edited The Memoirs of Alice Guy-Blaché in 1986.

Holly Weaver on La Souriante Madame Beudet (1922)

Six years prior to the release of her riot-inducing surrealist film La Coquille et le Clergyman, Germaine Dulac was exercising her female gaze in what would later become a feminist classic: La Souriante Madame Beudet. The film’s eponymous hero (Germaine Dermoz) is an intelligent woman who, when she’s not seeking solace in books or playing piano, sits at the receiving end of the selfishness and “suicide jokes” of her buffoonish husband (Alexandre Arquillière), whom she despises.

Although at first her subtle expressions portray a sense of apathy toward him, her thoughts and dreams tell us otherwise. Through the use of close-ups, mental images, and superimposition, Dulac allows us to delve into the psyche of her protagonist as she fantasizes about other men and being rid of her husband. However, as her feeling of imprisonment intensifies, these fantasies turn into nightmares since she cannot shake the image of Monsieur Beudet appearing around every corner, trapping her in an endless cycle of torment.

The motif of the “façade” is central to the film: the opening exterior shots of the tranquil village are betrayed by the gradual discovery of what is occurring behind closed doors, just as Madame Beudet’s “smiling” façade is belied by insight into her mind. Dulac’s commitment to the dichotomy between interiority and exteriority is further enforced through her use of light and shadow, creating a perpetual chiaroscuro. Nowhere is this contrast more striking than on the face of Madame Beudet herself, particularly while she sits at the window staring out with a deep tristesse, the presence of light and dark expressing both her fear of leaving and her reluctance to stay. Dermoz’s ability to covertly portray Madame Beudet’s inner torment is astonishing—whether it’s a look of disgust as she watches her husband sloppily eating dinner or a look of bitter hatred as the sheer mental image of him breaks her blissful reverie. Although Madame Beudet’s gestures become more erratic as she reaches a breaking point, her facial expressions retain a sense of impenetrability, unlike those of her husband, whose wide eyes and wicked grin give him the appearance of a maniacal clown from start to finish.

The film’s climax sees Monsieur Beudet playing his “suicide joke” once more by holding a revolver, which Madame has preemptively loaded, to his head. However, this time he turns it on her and fires a shot—but misses, and immediately runs over to comfort her. Thinking she intended to kill herself and not him, he begins smothering her with affection and ponders aloud, “How would I have lived without you?” Monsieur Beudet’s false assumption about Madame’s mentality shows the importance of the female gaze in film: a woman-led exploration of a woman’s psyche can provide an intimate portrayal of how the struggles we face run much deeper than what appears on the surface, as Dulac demonstrates so perfectly in her masterpiece.

Holly Weaver is a fourth-year BA French and Spanish student at the University of Leeds. After graduation, she hopes to earn a master’s degree in film studies.