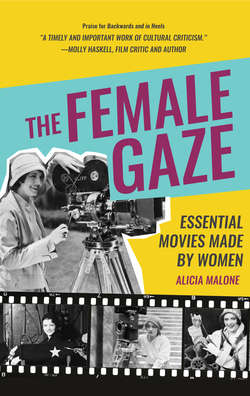

Читать книгу The Female Gaze - Alicia Malone - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеDance, Girl, Dance

RKO Radio Pictures, 1940, USA | Black & White, 90 minutes, Drama

A complex female friendship/rivalry between two dancers

of opposite styles.

Director: Dorothy Arzner

Producer: Erich Pommer

Cinematography: Russell Metty

Screenplay: Tess Slesinger, Frank Davis, based on a story by Vicki Baum

Starring: Maureen O’Hara (“Judy O’Brien”), Louis Hayward (“Jimmy Harris”), Lucille Ball (“Bubbles”), Ralph Bellamy (“Steve Adams”), Virginia Field (“Elinor Harris”)

“I was averse to having any comment made about being a woman director…because I wanted to stand up as a director and not have people make allowances that it was a woman.”

—Dorothy Arzner

There’s a moment in Dance, Girl, Dance which may elicit spontaneous applause. The scene comes toward the end of the movie and features a scathing speech about the objectification of women for entertainment purposes. And this impassioned speech may also make the audience think about how they too have unfairly judged these characters.

Dance, Girl, Dance follows a female dance troupe trying to make a living. At the center of the group is Judy O’Brien (Maureen O’Hara), a shy brunette who hopes to elevate the art form using her ballet routine. This places her in direct opposition to another dancer in the group, Bubbles (Lucille Ball), a feisty blonde who sees nothing wrong with using her sexuality to earn money. While performing together in Ohio, the two ladies meet and each fall for the same young man, Jimmy Harris (Louis Hayward), who is going through a messy divorce. Their fight for his affection continues in New York, where the troupe moves in search of work.

In the big city, Judy aspires to join the American Ballet Company. Her efforts are encouraged by the leader of the troupe, Madame Basilova (Maria Ouspenskaya). But when Bubbles finds fame in a burlesque show performing under the name Tiger Lily White, she hires Judy to get the crowd excited before the main performance. When Judy performs her ballet routine, she gets only jeers from the audience, who have after all come to see women strip.

The female friendship at the center of Dance, Girl, Dance is quite complex. Bubbles and Judy view each other as rivals, because that is what society has led them to believe. At the same time, the two women do help each other out; and it’s clear that underneath it all, they care for one another. In this way they’re like an odd couple or two characters in a buddy movie.

Both women are also trying to move out of the social class they were born into—Bubbles through money and fame, Judy through art and respect. Here, dance is not only a form of self-expression, but a way for both women to become financially independent. And the contrast between Judy’s elegant ballet and Bubbles’ sexy burlesque numbers reflect the divide between what was considered “low” or “high” theater at the time.

These characters are not one-dimensional. Bubbles is not simply a “bad girl.” Her insecure pursuit of fame is actually a little tragic, while at the same time, it feels empowering to watch her embrace her sexuality. She feels no shame, and the movie does not shame her. Bubbles just has that extra “oomph” that everyone is searching for. Similarly, Judy is not just the “good girl.” She is innocent but not naive, with a lot of burning ambition inside her. And if pushed too far, she snaps.

This brings me back to that pivotal scene. Without spoiling the moment too much, there’s a point where Judy has had enough of the crowd. She is trying to perform her ballet routine, but they only yell at her to take her clothes off. Judy stops dancing and walks to the front of the stage, where she crosses her arms and stares at the audience. “Go on. Laugh!” she says. “Get your money’s worth. Nobody’s going to hurt you. I know you want me to tear my clothes off so you can look your fifty cents’ worth. Fifty cents for the privilege of staring at a girl the way your wives won’t let you. What do you suppose we think of you up here—with your silly smirks your mothers would be ashamed of? We’d laugh right back at the lot of you, only we’re paid to let you sit there and roll your eyes and make screaming clever remarks. What’s it for? So you can go home and strut before your wives and sweethearts and play at being the stronger sex for a minute? I’m sure they see through you just like we do!”

It is a searing, powerful moment—and one which is as much about movie audiences in general as it is about the jeering audience in that particular theater. It’s as if Judy (or perhaps Dorothy Arzner) is confronting all of us, about how we have been looking at and judging the women in the film. It is a comment on how women are seen simply as objects to look at, expected to strip for our viewing pleasure. And it’s important to note that the crowd in the movie are not all men. There are women there too, who squirm uncomfortably during Judy’s speech, also guilty of imposing the “male gaze.” But crucially, it is a woman who is the first to stand up and applaud Judy’s speech.

The film does not, however, make things so simple for its protagonists. Judy has reclaimed her power and is about to leave the stage when Bubbles slaps her. This starts a vicious fight which spills out onstage in front of the crowd. So in the end, the women denigrate themselves for entertainment, just as the audience wanted.

Dance, Girl, Dance is a “backstage” musical that was created almost entirely by women. The original story was written by Vicki Baum, author of Grand Hotel, which was released as a film in 1932. Like that of Grand Hotel, Baum’s concept for Dance, Girl, Dance also features complex women with dreams and higher aspirations. This story was turned into an original script by Tess Slesinger with additional work by Frank Davis. Slesinger was a novelist as well as a screenwriter, and one of her short stories was the first be published in America that featured an abortion. And of course, the director of Dance, Girl, Dance was Dorothy Arzner, the only female filmmaker working in the studio system in the 1930s. She continued to direct until the early ’40s, and Dance, Girl, Dance was her penultimate (but most famous) film.

This is all the more interesting given that Dorothy Arzner was never supposed to be its director. Roy Del Ruth had been hired by RKO producer Erich Pommer because of his experience in the world of musicals, having directed three such films for MGM, all starring Eleanor Powell. But with Dance, Girl, Dance, he struggled to find a clear vision for the story. Soon after filming commenced, he was fired by Pommer and replaced by Dorothy Arzner. Arzner had only limited musical experience, having codirected Paramount on Parade in 1930, but brought with her a talent for crafting feminist films featuring complex women. Once hired, she significantly reworked the script and reshot every scene that Del Ruth had completed.

Arzner made two important changes to the story. First, she enhanced the central conflict by focusing on the difference between the two dancers. “I decided the theme should be The Art Spirit versus the commercial Go-Getter,” Arzner later said. Then she also changed the character of the male head of the dance troupe to a woman—from “Basiloff” to “Basilova.” This added another interesting female relationship to the story, that of student and teacher, which was given further complexity thanks to a few lingering looks Madame Basilova directs at Judy. And with Basilova’s slicked back hair and necktie, the new dance troupe head looked a little like Dorothy Arzner herself.

Arzner was an outlier in Hollywood. The only female director who made the transition from silent film to sound, she dressed in suits and was an outspoken feminist and lesbian at a time when nobody was “out.” She claimed to have been born in 1900, though all her records had been lost in the San Francisco earthquake in 1906. After the earthquake, her family moved to Los Angeles, where her father ran the Hoffman Cafe. The café became a favorite hangout for movie stars, and it was there that she met William C. DeMille, brother of Cecil B. DeMille. William gave Arzner her first job in Hollywood, where she started out as a script typist and later as an editor. But she knew from the beginning where she wanted to end up. “I remember making the observation, ‘If one was going to be in this movie business, one should be a director because he was the one who told everyone else what to do.’ ”

As a film director, Arzner was commercially successful, making movies featuring female protagonists across many different genres. Her movie Christopher Strong in 1933 gave Katharine Hepburn her first starring role, as a female aviator.

The reaction to Dance, Girl, Dance when it was released in 1940 was lukewarm. The film was buried and forgotten, receiving only poor box office results. Reviews were fairly positive, but most of the praise went to Lucille Ball. This was one of her first starring roles, and it was obvious she was something special. “If RKO accomplishes nothing else with the venture,” one reviewer wrote, “it has informed itself that it has a very important player on the lot in the person of Miss Ball, who may require special writing. But whatever the requirements, she has the makings of a star.”

After Dance, Girl, Dance, Dorothy Arzner made just one more film, First Comes Courage, released in 1943. During production, she contracted pneumonia and was so sick that director Charles Vidor had to come on board to finish the movie. Arzner recovered from that illness but retired from making movies. She continued to direct, making fifty Pepsi-Cola commercials for her good friend Joan Crawford. In the 1960s, Arzner began teaching at UCLA, where her students included a young filmmaker by the name of Frances Ford Coppola. In 1975, she was given a tribute by the Directors Guild of America. Four years later, Dorothy Arzner passed away at her home near Palm Springs.

It was only in the 1970s, thirty years after its release, that Dance, Girl, Dance finally found a receptive audience. Thanks to essays by writers such as Pam Cook, Claire Johnston, and Judith Mayne, the movie was rediscovered and reevaluated and became something of a feminist cult classic. During this time, analysis of the “male gaze” in classic cinema was gaining traction. As many of these writers noted, though Dance, Girl, Dance scorned the objectification of women, it was also itself guilty of it—demonstrating the limitations of classical Hollywood, even with a female director behind the lens. Other film critics were simply excited to discover the story of Dorothy Arzner. She was a rare woman in film history who achieved success within an extremely male-dominated industry.

THE FEMALE GAZE

The scene with Judy’s speech to the audience is a scathing commentary on the way women are used in entertainment. Dorothy Arzner’s camera makes it seem as if Judy is talking straight to us, and in a way, she is; she invites the audience to consider how they have been treating the female characters in the movie so far.

FAST FACTS

★Dorothy Arzner directed four silent films and thirteen talking pictures between 1927 and 1943. She is also the inventor of the boom microphone. On the set of The Wild Party, released in 1929, Arzner placed a microphone on the end of a fishing rod to give her actors more room to move.

★The working title for Dance, Girl, Dance was Have It

Your Own Way.

★Similar to the characters they played, Lucille Ball and Maureen O’Hara had a competitive relationship, though it remained friendly. In her memoir, O’Hara wrote that they “enjoyed a competitive rivalry on petty and harmless things, like fighting over which of us would get the dance stockings without the ladders or runs.”

★Following the filming of their big fight scene, O’Hara and

Ball went to the studio cafeteria for lunch. It was at that moment, with her clothes torn and her hair a mess, that Lucille Ball first laid eyes on Desi Arnaz. It was love at first sight—for Ball, at least.

Sumeyye Korkaya on Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon is a critically acclaimed work in American experimental cinema. After watching it, one might have the urge to spew a number of quizzical expletives. This is not uncommon, given Deren’s incredible usage of the surrealist form to create a dreamlike experience. The intense cut sequences only heighten the audience’s anxiety, and by consequence, portray the distortion of reality. The film is indeed a mesh of the afternoons experienced by a woman played by Maya Deren. The repetition in each scene is unmistakable due to the continuously reappearing objects.

After processing Deren’s frighteningly authentic vision into the female psyche, one can’t help but parallel this experience to that of gaslighting. Gaslighting is a form of manipulation within intimate relationships that causes the victim to forget their very self. The abuser holds power by contorting reality to his liking and distorting memories for his benefit. In Meshes of the Afternoon, the central figure desperately attempts to piece together her memories with three main objects: the flower, the key, and the knife. These are symbolic objects alluding to romance, privacy, and violence respectively.

Rather than display the timeline of events, Deren sequences the film in a way that permits the audience to experience the emotional turmoil behind gaslighting. This act of prioritizing emotion over rigid time structures dismisses the gendered division between emotion and logic. While mainstream film productions are subjected to the male gaze, the abstract and independent nature of avant-garde films allows for some escape. Meshes of the Afternoon explores the volatility of gaslighting through surrealism and the rejection of the male gaze.

Sumeyye Korkaya graduated from the University of Michigan with a Women’s Studies degree. She loves cultivating relationships with her sister-friends by dissecting romantic comedies, planning exclusive soirees, and blueprinting a future women’s resort.