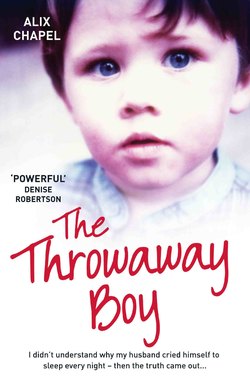

Читать книгу The Throwaway Boy - Alix Chapel - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Cardiff

ОглавлениеHe sat looking at the Christmas tree. The sound of children playing outside could be heard through the closed window. He didn’t want to play. He just wanted to stay sitting in the big chair. He could feel the tears prickling his eyes. He swallowed hard, trying to get rid of the lump in his throat. He was confused and didn’t understand what he had done to deserve being brought to that place.

Shortly after he had arrived, a lady came to get him and showed him where he would be sleeping. He thought she must have made a mistake because surely he wouldn’t be staying overnight. He desperately wanted to go home. When he got up enough courage to ask the lady when he could go home, she told him, in a matter-of-fact tone, he couldn’t.

He knew some lads from the estate who had been taken into care so he figured that that was what was happening to him. It was just his luck to be taken away so close to Christmas. It wasn’t as though he would miss much, though. Father Christmas always seemed to miss their house. Billy thought it was because, with the street being so dark, he couldn’t see the houses. The street lamps were smashed. They had always been smashed – well, at least for as long as he could remember. Father Christmas didn’t leave any toys at the other houses either, so he felt sure it wasn’t because he had been naughty. Anyway, there was no way he would find them that year. Not only were the street lamps broken, but their house was in total darkness as well. Billy’s mam, Hannah, hadn’t been able to afford to put any coins in the electric meter for ages. When there had been a choice between paying for gas or ‘lecky’, gas always won. Of course, sometimes they had neither. Billy didn’t mind all that, though, he just wanted to be with his family.

In the children’s home that Christmas, Billy was given a toy gun, but he would have given it up in a flash if it meant he could go home. He still didn’t understand why he had been taken away from his mam, brothers and sisters, but he figured it must have had something to do with his father. He thought of him and his anger once again surfaced, as it always did – but then even more so. He was upset and confused by his leaving and hated to see his mam so unhappy.

He was a very sensitive and ‘knowing’ little boy, more so than his two older siblings, and even more so than his twin. Perhaps that was why he was the one who was acting up. The others, oblivious to their mother’s struggle, just carried on, while Billy, taking it all in and becoming increasingly angry, frustrated and completely helpless, rebelled. Even though Hannah’s plight was nothing to do with him, he felt responsible.

There was no doubt that things had gone downhill since his father had left, especially financially, although life hadn’t been that great before. Hannah bore the brunt of her husband’s ways and sheltered her three youngest children from a great deal. He was a violent man who drank too much and was very selfish. His money was spent on himself – and his wardrobe full of suits – while the children often went without.

By the time he walked out on them, Hannah was worn ragged. She was devastated that her husband had left, and still loved him, despite his treatment of them. She had been used to just getting by, always having to try to stretch what little money he gave her but, on her own, there often just wasn’t any money at all.

Everything suffered as a result that first year. All the children were undernourished, but even so they grew out of their clothes and, of course, there was no money to buy new ones. Then, as a result of not eating properly, Billy wasn’t able to concentrate and was getting behind with his schoolwork. That was particularly hard as Billy’s twin, Jon, was also in the same class and he wasn’t having difficulty, which bothered Billy all the more. Gradually, he began to dread going to school and started playing truant. His mam was so fraught that, to begin with, she hadn’t noticed – and then, when she did, it was just another one of those things that she didn’t discipline him over. She was too tired and caught up with getting through her own day and looking after Billy’s little sister, Lauren. Eventually, Billy was taken into care and, even though he had been through some bad experiences before being taken away, he entered the children’s home a naive, sensitive, vulnerable little boy. He cried himself to sleep every night but then, after a while, he stopped, already becoming hardened by the experiences of his first few weeks.

In the beginning, before he started running away from the children’s home and lost the privilege, Billy was allowed back home to his family. He hated being in the children’s home but found the times back with his family equally as upsetting. He felt like an outsider and hated not feeling part of the family. He began to think that it must be his fault, especially since he had been the only one taken away. He would get himself so worked up that all the feelings of frustration, anger and bitterness would spiral out of control. It happened every time he was home. He would get there and all his good intentions of behaving properly would go out the window when faced with the situation at home. He felt so misunderstood.

He didn’t mean to be naughty, he just couldn’t control his feelings and vented them without thinking of the consequences. He would misbehave, get into trouble and, inevitably, his social worker would find out and he would be sent straight back to the children’s home. Ironically, even though the time spent at home was so hard – emotionally as well as physically – he spent the whole time he was away pining to go back. He built home up so much in his mind while he was away, imagining how it was going to be, setting himself up for disappointment and upset every time, but never getting to the point where he didn’t want to go home.

Billy had apparently been made a ward of the court so the local authority could do a better job of caring for him than his mother could. Ironically, the opposite was true. It was hard enough for any child to be taken into care, even when they were being rescued from bad parents, but, when the experience in care was far worse than what he would have endured if he had remained with his family, it was tragic and inexcusable. At seven, when other boys were playing cowboys and Indians and marbles, Billy was becoming accustomed to a life without love or protection.

In those first few months, coping with life in and out of the homes, Billy was under the illusion that was as bad as things could get. He had been through such a lot of turmoil and it had been far from easy, but it couldn’t have occurred to him that, compared to what lay ahead, life then was actually not that bad.

* * *

Later, when everybody had gone home, I gingerly asked Billy if anything was wrong.

‘No, love, I’m just tired,’ he replied.

‘Billy, you seemed miles away. What were you thinking about?’

‘Nowt!’ Billy’s voice was laced with anger and the fall into dialect seemed evidence of his mood.

‘Well, I know something is bothering you. Why won’t you tell me?’ I pleaded.

After a few moments of silence, when I feared his mood could have gone either way, Billy, in a quiet, subdued voice, just told me that the selection pack had made him feel sad.

‘Why? Did it make you homesick?’ I asked.

Billy sighed. ‘No, love… I never got a selection pack when I was a lad. I don’t even know if they were around then. Most of the time we just got an apple and a manky orange in an old sock. Although I do remember getting a toy gun one year.’

‘From your mum?’ I asked.

‘No,’ he mumbled and quickly changed the subject. Billy’s memories could flood in like a high tide at times but, like sea water, they usually retreated before he could properly grasp them – not that he particularly wanted to.

That night, lying in bed, I felt so sorry for the ‘little’ Billy. I knew he hadn’t had a childhood like mine and that they were really poor, and I knew he had spent time in children’s homes, but I didn’t realise just how much his childhood had obviously affected him. I felt guilty for all my reminiscing.

* * *