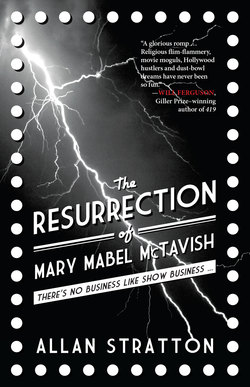

Читать книгу The Resurrection of Mary Mabel McTavish - Allan Stratton - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLife in the Vineyard

Brother Percy Brubacher would live to regret finding Mary Mabel in the Holy Redemption trailer-truck, would live to curse her name and all her works, fulminating from soapbox pulpits on Los Angeles street corners to the cell of the prison where he would be held on charges of kidnapping and murder. Yet at the time, finding Mary Mabel made Percy feel as close to Heaven as he was ever likely to get.

Now forty, he’d been undergoing a spiritual crisis. The promise of his first years evangelizing had turned to dust and he’d found himself in a pitched battle with the Forces of Darkness. “Help me, Jesus!” he’d scream in the middle of the night; but the Lord was not to be found in those lonely small-town hotel rooms with their peeling flowered wallpaper, mouse droppings, and tick-infested sheets.

Percy would leap out of bed in a frenzy and ferret from his suitcase the little black books in which he’d written up the history of his ministry, a literary labour undertaken as an assist to future biographers. He’d seek inspiration from page one, volume one, “The Day I Got the Call,” a recounting of the morning he’d stood, age five, in the alley behind his family’s bakery in Hornets Ridge, and served a communion of day-old Chelsea buns to a congregation of squirrels and chipmunks. As the rodents munched, tiny claws pressed together as if in prayer, the clouds had parted and a halo of sun had shone down around him, the sign of God’s anointing.

Percy’s mother encouraged his call, taking him to local meetings of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. He was an immediate sensation in his little blue blazer, grey flannel shorts, and bow tie, leaping to his feet as the Spirit moved, to preach away on the evils of drink. His father, a backsliding Baptist with a taste for bathtub gin, was none too pleased at his son’s denunciations. But as Percy reported, “The old devil said little, being generally passed out.”

While Percy’s religious vocation was attractive to rural women of a certain age, it caused trouble with the village boys, especially at recess, after he’d trumpeted their sins in front of the teacher. Percy didn’t mind. He wore his shiners proudly. “The badge of the Lord,” he called them. “‘For so persecuted they the prophets who came before me.’”

He took comfort from a postcard he’d received from famed baseball player-turned-evangelist Billy Sunday. Sunday had been touched by the letter from the little boy from New Hampshire, who’d written for advice on how to handle an alcoholic father. His reply became Percy’s salvation, recognition from the next best thing to God Himself that he mattered in the world beyond Hornets Ridge. He waved the postcard under everyone’s nose, made it the frequent subject of school Show and Tells, and created a small shrine to it next to the Bible by his bed. At night, he’d kneel, clasp it in prayer, and, running his finger gently over the postage stamp, listen to the still voice of the Lord.

“Yea, God spake unto me through Reverend Billy’s postcard,” — (volume one, page 126) — “revealing a Great Plan, a Divine Destiny for His humble servant. In cause of my deep and abiding faith, He promised that the day would come when I would be summoned to preach His Gospel throughout the land, and would be known, now and for all eternity, as the greatest of His prophets in the New World.”

Like all prophets, Percy endured a time of testing. In his early twenties, he wandered off for a prayer retreat atop Mount Pawtuckaway. From its peak, he saw the fiery furnace of Shadrach, Meeshach, and Abednego brought unto Hornets Ridge. His father, in a drunken stupor, had pitched a tank of kerosene into the bakery oven; his family died instantly in the explosion.

Percy anguished. “Why had I been saved, while my mother and siblings had perished? The Lord spake unto me in my agony. He had need to temper my faith, He said, the better for it to withstand the temptations of Hell.”

Percy retreated to a shack outside the village. Here he prayed without cease, readying himself for the promised day when God would summon him to mission. A few elderly women who remembered him from the W.C.T.U. left plates of food and spare coins outside his door, but this was the extent of his following. Even village clergy kept their distance; they resented being called to account by a hermit half their age. Children, emboldened by their parents’ mockery, threw stones as he passed. He paid them no mind, his eyes alight with glory. Let them call him “Beggar Loon” and “Scarecrow”; he’d have the last laugh.

Sure enough, when he hit thirty, God smiled on His poor servant. Reggie Burns, praise Jesus, went and blew the heads off himself, wife Nellie, and Pittsburgh playboy Junior Bennett — and Percy Brubacher got his break.

Within four days of the murders, the Bennetts put their estate on the market, and sold its contents at auction. In “Sinner On My Doorstep” — little black book, volume three, pages 21 to 50 — Percy recalled the curious visit he’d received that evening from Floyd Cruickshank, a former classmate who minded the till at the general store where Percy bought soap, macaroni, and tacks. Floyd, ever the would-be dandy in his secondhand worsted windbreaker and matching plus-fours, rocked on the heels of his Oxfords and asked, “Could I have a word?”

Percy was wary. Since their school days, the most Floyd had ever said to him was, “That’ll be sixty-five cents.” But the Lord put a flea in Percy’s ear, so Perce said, “Fine.”

After a little this-and-that about the weather, Floyd got down to business. He’d been at the auction. “All day, folks ponied up to buy the Bennett’s effects. They claimed they wanted a piece of history. Bull. What they really wanted — you could see it in their eyes — was a piece of secondhand sin. They wanted to hang their hats on the rack where Nellie hung her cloth coat, or put their lips on Missy Bennett’s bone china, or — pardon my French — have a bounce in the sheets of a murdered adulterer.”

Percy nodded grimly. He imagined Satan’s flames licking the pillowcases.

“At the end of the day,” Floyd continued, “everything sold but the tent. No surprise. It’d take a pretty big backyard. Even repaired, the stains’d put a damper on get-togethers. Which is why I got it free for the hauling.”

Percy’s heart raced. “You got the tent?”

“Amen.” And now Floyd got serious. “Perce, we’ve known each other since we were kids. I’m ashamed to say I did you wrong.”

Percy could hardly breathe. He was suddenly back in the playground, swearing down God’s vengeance, as Floyd cleaned his clock. Again and again and again.

“I’m here to say I’m sorry,” Floyd said.

Percy’s eyes welled. “You’re sorry?”

“Yes. I’m sorry. Very sorry. Forgive me?”

The next thing Percy knew, he was hugging Floyd and sobbing on his shoulder. Floyd eased him onto the porch step and handed him a handkerchief.

“I’m no do-gooder,” Floyd said quietly, as Percy blew his nose. “I’m just a sinner who wants to get the hell out of Hornets Ridge. That bloody tent’s my main chance. All afternoon, I’ve thought, if folks find thrills in tea towels, what’ll they find in the tent of horrors itself? Only thing is — I can’t just sell tickets. Respectable folks’ll need an excuse to go inside.”

“Maybe a sermon?” Percy blurted. He shook his fist over his head. “That tent is the Lord’s living proof, The Wages of Sin Is Death.”

“My thought exactly,” Floyd enthused. “A God-fearing barn burner on that theme’ll pack ’em in. But heck, Perce, I’m no speaker. I can barely sell toothpicks, much less God.”

“So the Lord has sent you unto me!”

“More or less.” Floyd stuck a finger in his collar. “I remember school, Perce. You gave me nightmares for weeks. No kidding. You were one scary bugger. So here’s what I’m driving at. You’re a preacher without a pulpit. I have a pulpit without a preacher. Whadeja say?”

“I say the Lord has worked a wonder in your heart, Brother Floyd!” Percy wrung out the handkerchief and gave his eyes another wipe. “Yea, it be murder, suicide, adultery, and drink have brung this tent unto us, but through our ministry shall innocent souls be snatched from the Pit. Oh Brother Floyd, I say unto you, all things work together for good for those who love the Lord. Let us pray.”

By midnight, Brother Percy was packed; he had but his Bible, his postcard, a few old clothes; a second pair of shoes, the soles patched together with squares of birch bark, bicycle tires, and tacks; a toothbrush and a comb; and his emerging set of little black books. Unable to sleep, he lit his kerosene lamp, and wandered to the cemetery to spend his last night in Hornets Ridge beside his mother’s grave. As he later wrote:

I knelt beside the wooden cross that marked dear Mother’s resting place and traced the grooves of her name with my finger. “I won’t be able to come by so often, Mother,” I said, “for God has laid a mission on me. But you already know that, smiling down from Heaven. You’re the only one who believed in me, who never made fun, besides blessèd Billy Sunday. As he wrote in my postcard, ‘From a little acorn will grow a mighty oak.’ It’s true. For I’m growing, feet planted in the Word of God, arms branched open in the Light of the World. Before I’m through, I’ll be as famous as Brother Billy. More famous, even. They won’t laugh at me then. They’ll bend their knees and pray before me. I’ll make you proud, Mother. I’ll be crowned with glory and have money enough to buy you the biggest stone in the whole darn cemetery. Better than a stone: you’ll have the statue of an angel. For that’s what you are, it’s what you deserve, and it’s what you’ll have, so help me God.”

For a time, God’s Promise looked to be fulfilled. As recorded in Percy’s little black books, those were the glory days, a time of redemption with Satan on the run. The Bennett murders packed the tent that whole first summer; and come frost, Floyd had finagled invitations from the Deep South, where righteous brethren from the hills of Arkansas to the Florida orange groves were keen on hellfire sermons featuring Yankee sinners bobbing in brimstone.

The collections had been equally good: love-offering envelopes sufficiently stuffed to keep up payments on the truck, and on that marble angel for his mother, which he’d got at a discount on account of the left wing being chipped in transit, though not so’s you’d notice, praise the Lord. There was even enough to shell out for beds in private hotels; these inspired more uplifting prayers than those delivered from lumpy mattresses in the basements of local deacons. Nor did the evangelists stint on such accommodation. As Floyd pointed out, “Jesus may have preached to whores, but stay in some flophouse, you think there won’t be talk?”

The evangelists also agreed that the Almighty wanted His employees to look their best. “Rags and sandals are fine for Bible times, but holes in the socks make a lousy advertisement for the Kingdom of God.” So Percy got himself outfitted with two navy, off-the-rack suits from Tip Top Tailors, three starched white shirts, one pair of suspenders, and a snazzy charcoal-grey fedora.

Percy kept a careful tally of all such expenditures on the flesh in his little black books. Here, too, he recorded tallies of the tent’s nightly take, as well as the count of those who hit the sawdust trail, parading up the aisle to fill out decision cards for the Lord. Some of these converts made a habit of getting saved. If Percy knew, he didn’t let on. He was proud of his numbers, and prayed they’d be celebrated like those of his hero, Brother Billy, whose salvation stats had been touted in box scores on the front pages of dailies from L.A. to Washington, Albuquerque to New York.

Percy’s triumphs, however, went unheralded. Local reporters covering the arrival of the tent simply wrote a rehash of the murders. “Those degenerate fornicators get more ink than I do,” Percy groused. To add insult to injury, no one appeared to know how to spell “Brubacher,” an indignity that invariably set Percy to work on some variation of the following letter-to-the-editor.

Dear Buttonbrook Gleaner,

Buttonbrook should count itself good and lucky to have had the internationally renowned revivalist Brother Percy Brubacher preaching out at the bandstand last Saturday night. He has chased the Devil out of Arkansas, Rhode Island, and points between. So it is a crying shame that your editor is so ignorant as to spell his name with a “k.” This is an embarrassment to your paper, a black day for Buttonbrook, and an insult to the Reverend Brother Brubacher, who is more famous than the lot of you put together.

Yours sincerely,

Mr. Herb Potts

As time rolled on, attendance at the tent began to thin. The Bennett killings were stale, jostled out of the spotlight by Al Capone, the Lindbergh baby, and above all else the fallout of the Great Crash. It’s hard to raise a sweat over the death of some playboy when big city skies are raining bankers.

The Depression did more than upstage their act. While a few churches continued to play host, most cut off invitations lest dwindling tithes be siphoned to the competition: charity begins at home. Consequently, Brothers Percy and Floyd had to underwrite production costs, while fending off accusations that they were stealing bread from the mouths of local widows and orphans. It was a strain, especially as the offering envelopes they were accused of filching were increasingly stuffed with newspaper.

Costs up, revenues down, the evangelists scaled back. They lodged at modest bed and breakfasts, which had the attraction of landladies prepared to darn socks, or raise pant hems to disguise frayed cuffs. There was a price for this needlework: widows with a clutch of dead lace at their throats and habitations appointed with dusty bouquets of dried flowers. Such would insist on favouring them with recitals at the parlour piano. “Do you ever dream of domestic bliss?”

The Widow Duffy was a terror in this regard. Her attentions to Brother Percy caused the poor man much consternation, especially at night when she prowled the corridors, ultimately surprising him in the biffy. “Get thee behind me Satan,” he cried, scrambling to cover his privates. The Widow Duffy claimed herself an innocent sleepwalker, but Percy was no fool. “She meant to have her way with me,” he whispered to Brother Floyd. “We must quit this den by daybreak: ‘Flee from temptation, nor let the shadow of it come nigh!’”

While Percy knew the Bible, he scarcely knew himself. Sex was no temptation to him whatsoever. An enthusiastic virgin, he held the entire process to be as distasteful as it was messy, a dirty chore necessary to propagate worshippers. Fortunately, being a preacher, he’d been given a more dignified means to populate the Kingdom, and a damn sight more sanitary to boot.

Floyd, on the other hand, laboured under no such misapprehensions. Frankly, the Widow Duffy’s nocturnal ramblings had aroused more than his curiosity. “Brother Percy,” he admonished, “we have a Christian duty to remain. If that dame sleepwalks unattended, she may fall down the stairs and break her neck.”

“Don’t think to pull the wool over my eyes,” Percy scolded. “You’ve a mind to spill your seed in that harlot! How shall you answer up to Jesus at the end time?”

“Nag, nag, nag. If I wanted a wife I’d have married one.”

“Repent or burn!”

“Go suck an egg.”

Percy stormed off, spending the rest of the night at the local fleabag. He didn’t sleep. Then again, neither did Floyd. Yet whereas Percy spent the morning’s drive to the next town muttering into his Bible, Floyd was frisky as a pup, pedal to the metal, whistling rags. They stopped for gas. Brother Percy closed the Good Book and held it to his breast. He cast a baleful gaze in the direction of his colleague.

Silence.

“What?” Floyd demanded.

God’s prophet flared his nostrils. “Apostate!”

Brothers Percy and Floyd never again shared accommodation. Percy confined himself to respectable S.R.O.s with sharp-eyed proprietors who snooped the halls to nix shenanigans amongst unmarried guests. Famous for shared baths with rust-stained sinks, the smell of mothballs, and the sound of lonely geriatrics weeping at all hours behind closed doors, these hotels were a perfect match for the evangelist. Once management realized he was alone, they paid no heed to his arguments with the dresser mirror.

Floyd, truth to tell, had always kept his pump primed. He’d simply held off till Percy’d fallen asleep, figuring it was better to sneak off like a kid out for a smoke than to set himself up for sermonizing in the truck. He’d had nightmares of being strapped to the wheel with Percy haranguing him from North Bay to Memphis. But discovery of Floyd’s appetites had put a cork in Brother Percy’s pipes; his censure registered instead by heavy sighs. This was a mite creepy on all-night drives, but a definite improvement over the yapping to which Floyd had hitherto been subjected.

As Percy’s private life grew progressively solitary, his nature became more bilious. “Billy Sunday wasn’t stuck in hicksvilles with a whoremonger! He was beloved! Adored! It isn’t fair!” His theology followed his mind into nightmare, his God transformed from disciplinarian to psychopath.

“The Lord thy God is a bloody god,” he’d rage across the stage, “His plan of redemption, a slaughterhouse dripping with the blood of the Lamb, our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ! Who’s off to the lake of fire? You know yourselves, you hell-born, hog-jowled, whiskey-soaked assassins of righteousness! You cigarette-smoking, fudge-eating lechers in spats and green vests! You hags of uncleanness dolled up in fool hats for card parties, serving spiced meats on hand-painted china with nasty music on your pianos while your spawn run the streets like a rummage sale in a secondhand store, gadding about in the company of jackrabbits whose characters would make a black mark on a piece of tar paper! Well, you’re off to judgment, my friends. You, too, Granny, your white hairs won’t save you from a swim in the Devil’s chamber pot! You’re off to a judgment fierce as that of those damnable rum-soaked Bennetts, suffocating in the rank, fetid sweat of their fornication, drowning in the juices of their abomination! A judgment fierce as Sodom and Gomorrah, when the Lord God made Mount Vesuvius puke a hemorrhage of lava!”

Congregations were disconcerted. In theory, they accepted that they were all sinners, but in practice it was generally understood that the preacher’s wrath was to be directed at sinners outside the tent. By the end, only Pentecostals had the stomach to attend. They could count on the Holy Spirit descending, transporting them with the gift of tongues, God’s proof-positive that they’d been saved by the blood of the Lamb and were bound for glory with Percy and the angels.

Floyd had known that life in the Lord’s vineyard was not for the upwardly mobile, but after expenses he barely had the scratch to pay for his French ticklers. He decided to pull the plug. He waited till they hit London, Ontario. Here Percy would be as happy as he’d be liable to get, haranguing one of the last crowds to consider him a somebody.

And so, the afternoon of that fateful revival, Brother Floyd moseyed his partner into the van of the trailer truck. “I’ve been doing some thinking.”

“Praise the Lord. The first step to repentance.”

Floyd bit his tongue. “The ministry’s had it,” he continued. “It’s time to call it quits.”

Percy staggered backwards. “Quits? Where would the world be today if Jesus had called it quits?”

“Our receipts don’t amount to a pinch of heifer dust,” Floyd persevered. “We’re a corpse begging to be buried.”

“And what if we are? Lazarus came back.”

“For heaven’s sake, Perce, you’re misery on a stick, you scare the kids.”

“God didn’t put us on this earth to be happy. We were put here to serve.”

“There’s other ways to serve.”

“Not for me! This ministry’s my calling. It’s where I belong. It’s my home.”

“It’s not your home, it’s a tent. Repeat after me: ‘This is a tent. A tent of horrors kept fresh with slaughterhouse guts and a paintbrush.’”

“Nooo!”

Floyd wasn’t good with tears, but he wasn’t about to let a wave of compassion sink his resolve. “Perce,” he stared in embarrassment over the poor man’s left shoulder, “I’ve been doing some calculations. There’s a way we can close up shop and go our separate ways with a little something to tide us over.”

Percy sniffled. The absence of other vocalizing encouraged Floyd to believe that reason had a prayer.

“We got ourselves seven thousand square feet of tent near as I can reckon. At four six-inch squares per square foot, that’s twenty-eight thousand squares. I propose we do one final farewell tour. Each night we’ll sell Redemption squares, to be cut from the tent and delivered at tour’s end: two bits a piece, or a buck for one with blood on it.”

Percy gaped like a gopher on a spit. “YOU’RE NOTHING BUT A GODDAMN STOOL UP THE DEVIL’S ANUS!” He hurled a folding chair at his partner and flew from the fairgrounds, tears of rage, horror, and helplessness flooding down his cheeks. “Dear God,” he beseeched, falling at the foot of a mighty oak, “steep me in Your wrath! Do such a Work through me tonight that it will tear the firmament!”

The next thing Percy knew, he was on stage screaming at Timmy Beeford, lightning shearing the main pole, ripping the wires, popping the light bulbs, exploding the generator — and his mother’s childhood caution ringing in his ears: “Percy, my pumpkin, be careful what you pray for. God may be listening.”