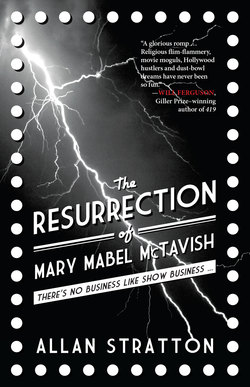

Читать книгу The Resurrection of Mary Mabel McTavish - Allan Stratton - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеResurrection

Mary Mabel could swear on a stack of Bibles about what happened when she arrived at Riverside Bridge. She’d climbed on top of the railing, peered down, and felt a chill at the sight of the river rocks. Her mama’s voice had rung in her head like church bells: “Let go. Let go.” She’d closed her eyes, stretched out her arms, and then … and then? She hadn’t a clue. The next thing she recalled was twirling barefoot, like a dervish, before a radiant young man bathed in light.

At the sight of the angel, she’d dropped to her knees in wonder. “Am I in heaven?” she asked. “Are you God’s messenger, Gabriel?”

“No, ma’am,” he replied, “I’m George Dunlop. Ambulance driver from London General.”

Mary Mabel shielded her eyes from the sun, and saw that her angel had chin stubble, pimples, and a grass stain on his left knee from scrambling down the embankment. They were standing on the rocks by the river’s edge. The driver looked embarrassed. “The Petersons spotted you,” he said. “They called for help. Are you all right?”

“I don’t know. Am I?”

He said she ought to come with him, which seemed a good idea. Though otherwise unharmed, her dance on the sharp stones had cut her feet.

Thing were slow at the hospital, typical of a Sunday. The town was taking the Lord’s Day to rest, what with Saturday night hangovers and church. Aside from a couple of orderlies and a janitor, Dr. Hammond was alone with his trusty sidekick, Nurse Judd. Dr. Hammond had been a drill sergeant on home duty during the Great War, and used his army whistle to boss the wards. He had a reputation as a crusty sonovabitch who saw the sick as a nuisance, and forestalled discussion by making their diagnoses as incomprehensible as possible. His motto, “What they don’t know won’t hurt them,” was a comforting thought, though patently untrue judging by his contribution to the local cemetery.

As Nurse Judd wrapped her feet in gauze, Mary Mabel imagined herself an Egyptian princess being prepared for burial, her grieving Pharaoh father leading the court in lamentations so profound that the river Nile o’erflowed its banks with tears. Meanwhile, Dr. Hammond was calling the Academy. He told the porter to inform Mr. McTavish of his daughter’s whereabouts. Then he returned, took out his notepad, and began asking Mary Mabel questions so silly she thought he was teasing.

“Do you know where you are?”

“Westminster Abbey.”

“What is the date?”

“1812.”

“Is George Dunlop the Archangel Gabriel?”

“Of course not, he hasn’t a trumpet.”

Dr. Hammond paused. “Are you a humorist, Miss McTavish?”

“No, sir.”

There followed a heavy silence animated by medical jotting. Mary Mabel glanced from Dr. Hammond to Nurse Judd. It was clear they thought she was crazy. She decided not to mention her conversations with her mama. “May I go now?”

“No. You’re to spend the night under observation, subject to your father’s approval.”

“Oh, he won’t approve,” she assured them. “I’m to be at work come five in the morning. Even if I was dead, Papa wouldn’t let me off my chores.”

Dr. Hammond furrowed his brow, muttered “melancholia,” and scrawled furiously in his notepad. At the mention of melancholia, Mary Mabel giggled, which made Dr. Hammond scribble even more. But the truth was, since her escapade at Riverside Bridge, Mary Mabel had been suffused with a joy so warm that nothing could extinguish it — not even the realization she was alive.

Nurse Judd escorted her to a sickbed to await Brewster’s arrival. “He’ll be along shortly,” she said. Mary Mabel knew otherwise. By the time the ambulance driver had found her, her papa would’ve read her suicide note and hit the bottle, terrified of impending scandal. The porter knocking would have sent him scuttling under the bed. It would be supper before he got word that she was alive, good news that would occasion a fresh bottle by way of celebration.

There were thirteen other beds in the ward, a long rectangular room divided by yellowing muslin privacy screens. Mary Mabel wasn’t sure how many souls she had for company, but counted at least eight: five coughers, two snorers, and a woman across the room with hiccups. Together with the hum of the ceiling fan, the rattle of the dinner trays, the squeak of the medicine carts on cracked linoleum, and the periodic buzz from the fly strips, they made napping difficult. By dusk it was more so, a snap storm beating a tarantella on the window panes.

Still, Mary Mabel daydreamed happily till eight, when she was overcome by an acrid waft of body odour, booze, and raw onions. Her papa had arrived, a buzzard in from the wet. She listened to Nurse Judd give directions to her bed, then closed her eyes tight shut as she heard the approaching squish of his soaked boots, the screen rolled back, and the sound of him slumping heavily onto the chair to her right. He sat in silence, save for the drip off his rain slick.

She opened her eyes. He was peering at her with the intent gaze of a stuffed bird. She pictured him on a mantel. “Shall

we go?”

A heavy groan. “I love you.”

“I know.”

He groaned again. “No you don’t. I love you. Very much. Very, very much.” A shudder. “Do you love me?”

“Of course, Papa. So, shall we go?”

“We can’t. We have to wait. The doctor’s with a patient. You’re the picture of your mama. I love you, Mary Mabel. I love you very, very much.”

Lord, Mary Mabel thought, how many times will he tell me he loves me before Dr. Hammond comes and rescues me? Spending the night at the hospital was beginning to look attractive.

Brewster horked a wad of phlegm and spat it in his handkerchief. More laundry. “I haven’t said a word to your Auntie Horatia,” he confided.

“I don’t have an Auntie Horatia.”

“Suit yourself. I’ve kept this from her all the same. It would drive her wild. And after all she’s done for you. “

“Please, Papa.” She indicated the world beyond the screen. “You’re shaming me.”

“No more than you shame me, with that cow face of yours.” He rose from his chair. “Hey, you folks with your ears in our business, my slut of a daughter ran off to kill herself!”

The woman across the room stopped hiccuping. Mary Mabel hid her face in her pillow.

Brewster fell back into his chair. “I’m sorry,” he wept. “I’m a bad father.” He wanted her to contradict him, but she wouldn’t. “I’m a bad father,” he snivelled again.

“So you say. Now be quiet. I’m alive. There won’t be a scandal. Lucky you.”

“How could you think I’d care about scandal if my little girl was dead?”

Mary Mabel laughed. Her papa looked so startled that she forgave him despite herself. She got up and kissed him on the forehead. He let out a wail. And that’s when the mayhem struck.

Down the hall, the emergency doors burst open and a flood of Pentecostals washed into the waiting room. A clatter of chairs and trays. Cries of “Doctor!” “Devils!” “Save us!”

Mary Mabel ran to the door of the ward and looked down the corridor. It was a war zone. Home duty had not prepared Dr. Hammond for a horde of Holy Rollers. He let rip with a toot on his whistle. “Smarten up. Get in line. Take a number.”

No one paid heed, least of all a frantic couple who’d clawed their way to the front with a lad as limp as a rag doll. “Doctor, please help,” the woman cried.

“Shush,” Dr. Hammond roared. “Can’t you see I’ve a riot to take care of?”

“But this boy may be dead!”

“Then take him to an undertaker.”

Her companion clutched the doctor by the throat. “Examine him now!”

Dr. Hammond peered at the youngster. The child’s face was a light blue, the lips purple. His jacket was burned through, the exposed skin raw. Orderlies kept the crowd back as Dr. Hammond ripped open his shirt, and listened through a stethoscope. “There’s no heartbeat,” he said. “How long has he been like this?”

“Twenty minutes.”

“Then you’re right. This child is dead.” Dr. Hammond scratched his initials on a death certificate handed him by Nurse Judd. The woman howled, but the doctor had no time for consolation. “I didn’t kill him. If you want a second opinion, go down the road to St. Mike’s.”

That was too much for the man. “Sorry, Jesus,” he exploded, “but I got business to attend to!” With that, he decked Dr. Hammond, leapt on top and pummelled away.

Mary Mabel felt her mama’s presence. “Go to the boy,” her mama said. The room disappeared. All Mary Mabel could see was the child. As if in a dream, she floated beside him. She knelt, smoothed his hair, and clasped his hands within her own. There was a whirring, a dark fluttering. Heat flooded her body, coursed down her arms, and out through her fingers.

It was then that the boy gave a cough. And a second. His chest began to move as he inhaled. His cheeks flushed. His eyelids twitched. Opened.

“Ow,” he said. “I hurt.”

Mary Mabel glowed. With her mama inside her, she’d raised the dead.