Читать книгу The Inventive Life of Charles Hill Morgan: The Power of Improvement In Industry, Education and Civic Life - Allison Chisolm - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHANGE IN DIRECTION

ОглавлениеMorgan seems to have lasted about three months at the dye house. During the fall of 1852, his diary entries change from Clinton to the new town of Lawrence, 38 miles northeast. He was clearly seeking new opportunities to learn and expand his network beyond Clinton. A local history of Clinton describes the September 1852 arrival of Peter Stevenson, 10 years older than Charles, and a man who had learned the trade of a dyer in his native Scotland. Stevenson was hired to become the overseer of the dyeing department of the Bigelow Carpet Company.

By the end of 1852, Morgan had left his position with the Bigelows and moved, leaving Harriet behind with his parents. This marked the beginning of several years when he maintained two households—one where he worked, and one where his family lived. While important for learning his trade and gaining work experience, this situation proved to be a constant strain on his finances.

There was a lot of work to be done in Lawrence, a town founded only seven years earlier with property carved out of Methuen and Andover by a group of businessmen who sought to establish water rights along the Merrimack River. They incorporated the Essex Company in 1845, capitalized at $1 million, and carefully designed the mills that would use that water power—the Atlantic Mill, the Duck Mill, and the Pacific Mills among them.

The business owners also took equal care planning the city, officially chartered just after Morgan’s arrival, in 1853. The Essex Company gave Lawrence the land for its town common, but with building restrictions on the types of property surrounding it, limiting development to churches, civic building and high-end homes only. It also gave the city property for worker housing, this time with specific requirements intended to ensure better quality living conditions.

The Essex Company had also built in 1846 the four-story stone building for the Lawrence Machine Shop, to manufacture and repair textile machinery for the mills along the river. By June 1853, however, the machine shop was legally an independent entity and advertising its services as steam engine builders and manufacturer of machinists’ tools.

A second diary kept by Charles in this period details specifics for the Pacific Loom, most likely within the Pacific Mill, which the Essex Company operated in Lawrence. Morgan’s diary also details his “contingent expenses” to support himself in Lawrence during December 1852, more than half of which included his $15 board bill, as well as many loaves of bread, quarts of oysters, pounds of beef, chicken and saltpork, 500 pounds of coal, one pound of chocolate, barrels of apples, and the latest issue of Scientific American magazine for four cents. He also spent 50 cents for a portrait of that beloved Massachusetts Senator and Secretary of State, Daniel Webster, who had died only a few weeks earlier.

Morgan labored from seven to 13 hours each day that December, working on drawings or designs, first for Pacific loom gears, shafting, and a boiler plate punch, and later in the month, for cams and levers for the Duck Mill’s loom. He did not work Sundays or December 25 or 26, when he probably travelled back to Clinton to see his family and attend church.

His former tutor, John C. Hoadley had a machine shop in Lawrence, and Morgan may have served as an hourly laborer for him. Sometime late in 1852, Charles glued an illustrated advertisement for “J. C. Hoadley Portable Engines” of Lawrence, Massachusetts, into his diary.

Through the first four months of 1853, Morgan worked for the vast manufacturing enterprise of the Essex Company, as his diary meticulously details the time he spent each day on projects for them. He must have felt secure enough in his position by late April to invest more than $22, several weeks’ wages, in his draftsman’s tools. The diary enumerated the expense of each item, which included a double point shaft compass for $5.25, a special German pen for $1.75, a set of 3-inch steel bows for $7.25, eight pens, a case and the velvet to line it for another $1.72.

He probably spent that first winter working in the Lawrence Machine Shop building, as an invoice dated May 31st for time worked that month is addressed to the Lawrence Machine Shop. Once separated from the Essex Company, the new enterprise hired as superintendent none other than John C. Hoadley.

While the long hours of work kept Charles busy, thoughts of home were never far from his mind. Postage was an ongoing expense. His brother Henry arrived in Lawrence on February 1, 1853, and started working for the Lawrence Machine Shop the next day. Charles’ work occasionally brought him back to Clinton, as one diary entry details a parts list of castings required for a steam engine for Bigelow Carpet.

Once Charles began working in Lawrence, however, Harriet, nicknamed “Hatty” by Charles, may have moved back to her parents’ home in Shrewsbury for a time. By the summer of 1853, she was pregnant with their first child. He took on extra work where he could, including 18 hours over six days in July drafting for Thomas J. Everett in Lawrence. Taking into account the ten cents Morgan had to pay for the linen cloth to mount his drawing, he earned about 25 cents an hour for the drafting job, netting $4.40. This work was on top of ten-hour days he logged for the Lawrence Machine Shop.

He was absent from work on July 21, as he was moving. The very next day, however, he reports working another 10 hours on the “15 x 35” stationary engine. He must have completed his work—and finished the move—by August 8, when he records more details on the steam engine—the distance its piston travelled per minute, the number of revolutions per minute the shaft made and the diameter of the pulleys required to drive the shaft. Further details on this engine fill up half a notebook he used at the time.

The work produced by the Lawrence Machine Shop gained attention far beyond Lawrence that year, as one of its stationary steam engines was exhibited at the country’s first international exposition, the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. Held in New York City’s Crystal Palace exhibition hall (in what is now Bryant Park) from July to November 1853, the exhibition included, according to Morgan’s notes, “order #812, Crystal Palace Engine, 15x35 Double.” Lawrence Machine Shop was among some 4,800 exhibitors from 24 countries to showcase their accomplishments. In the space of four months, more than one million visitors flocked to the iron-and-glass palace topped by an enormous glass dome.

Morgan remained in Lawrence, learning everything he could about steam engines, valves, looms, bevel gears, miter gears, turbine gears, spinning frames, shafts, collars, shells, nuts, bolts and set screws. He drew detailed illustrations of each piece of machinery and how they operated together. He would record new facts, and sometimes annotate them later.

“A man can turn 60 ft. of 2-inch shafting on one engine per day,” he wrote in April 1853. On the next page, he explains that in the Pacific Mill, “On #50 yarn, a card works 20 lbs. cotton per day or enough for 200 yds. cloth.” In another section, he helpfully notes how to calculate cotton yarn’s number: “Weigh any number of yds. of yarn, multiply the number of yds. by 8 1/3 and divide by the number of grains. The quotient = No. of yarn.” One yard of cloth has 840 grains, with 837 ½ grains equaling one ounce.

His notes reflect his interest in the larger business concerns of the day as Lowell saw rapid growth. In June 1853, he reported on what it cost to build a cotton mill in Lowell, noting “for a few years past has been $13.75 per spindle for the machine and $20.00 per spindle including buildings, etc.”

By 1854, the Lawrence Machine Shop had expanded into manufacturing boilers for railway engines while continuing to produce high level iron work. As Morgan detailed one customer’s specification for a September 1854 order:

Healy Holman Sons & Co. order the Iron work on 9 horse cars, 28 ft. long 9 ft. wide, inside of side sills same height as on car, 30" wheels axle bearing 2 ½ and 5 ½" cast iron bunter, safety beam, safety chains for brakes. Door with wrot iron grating and the centre hasp left out, also 6 platform cars same size ... Boxes to be of cast iron.

Attentive to business details, he then noted the price of wrought iron per pound (7.5 cents) versus the cost to his company (4.25 cents), for a 3.25 cent profit per pound. Terms were half cash on delivery (on board ship in Boston), with one-quarter draft on a railway company due in six months with seven percent interest, and the final quarter due in 9 months at 7 percent interest.

William T. Merrifield contracted with the Lawrence Machine Shop in early 1854 to build a steam engine for his Merrifield buildings in Worcester. Merrifield was well known in Clinton, as he had won the contract to build the Lancaster Mills and tenement houses, which he completed in 1848. While they were under construction, Merrifield moved to then-Clintonville for four years, the only period he ever lived outside Worcester. He joined the church Hiram Morgan helped to found, the Second Evangelical Church of Lancaster. When the church outgrew its first home in 1846, Merrifield was named to the building committee.

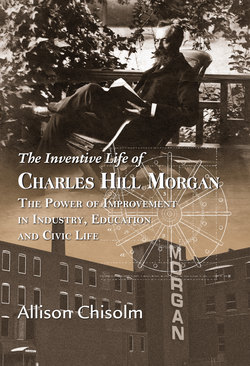

Postcard for the Lawrence Machine Shop

The Merrifield buildings, encompassing an entire downtown Worcester block, had gone through five successively larger steam engines as their demand for power grew. In what would be considered a small business incubator today, small manufacturing companies would lease space from Merrifield to tap into his power source for their enterprises. The buildings had suffered a massive fire in June 1854, and William Merrifield quickly set out to rebuild.

Before the fire, Charles was assigned to make preliminary drawings for the enlarged steam engine’s foundation. The engine would be heavy enough that the anchor needed to be sunk more than 5 feet into the stone foundation to hold it in place. One of Morgan’s drawings from March 1854 has been preserved. Produced on linen cloth common for the time, his drawing’s light pencil lines remain clear, as do the circles he made (with his special compass) to represent the clearance required above a foundation wall for a single engine piston and flywheel. Smaller circles indicate key intersections of machine parts.

Detail of Charles H. Morgan’s drawing of the foundation for a Lawrence Machine Shop steam engine

While Morgan continued his relationship with the Lawrence Machine Shop, in the fall of 1854 he moved back to Clinton. In what was likely common practice for rapidly growing but cash-constrained businesses of the time, the employer paid Morgan in early January 1855 for work performed in 1854, so he may have worked on drawings from Clinton, or made brief trips to Lawrence when necessary.

Charles moved back home for two reasons: the birth of his son Charles Henry, known as Harry, in February, followed by the death of his mother Lucina in July. By late October, Charles was selling off many of his mother’s possessions, carefully noting the buyer for each item and price. A man named Anderson bought for $16.68 a good portion of the household items, including a bureau, chairs, stove pot, four jugs, buckets, a bean pot, an enamel kettle, baking tins and a dust pan, cups, plates and saucers and even the parlor stove. For $14.50, “Davidson,” possibly someone Charles knew from his work in Lawrence, purchased a table, 20 yards of carpeting, a pair of flat irons, a bedstead, rocker, saw and horse, and two barrels of apples. Hiram Morgan either lived a Spartan existence after the sale of much of his home’s furnishings, or moved in with Charles, Hatty and baby Harry.