Читать книгу The Inventive Life of Charles Hill Morgan: The Power of Improvement In Industry, Education and Civic Life - Allison Chisolm - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THE POWER OF CAPITAL

ОглавлениеThe landlocked town of Worcester was built on a rocky soil that nonetheless proved to be fertile ground for mechanical ideas and improvements. Located 40 miles inland from Boston’s harbor, Worcester grew from a village of 2,700 in 1819 to a city of 32,000 in 1864, when Charles Morgan arrived to work in its metal industries. By the time of Morgan’s death in 1911, Worcester had become a bustling metropolis and industrial powerhouse of more than 145,000 people. A combination of practical ideas, ready capital, expanding transportation, innovative education and a diverse population brought benefits to the region beyond any predictions. Charles Morgan was one of many individuals who thrived in 19th-century Worcester’s atmosphere of mechanical improvements and economic development.

Encouraged by the success of the Erie Canal in the early 1820s, a group of Worcester businessmen, politicians and lawyers joined with Rhode Island merchants to bypass opposition from Boston and build the Blackstone Canal to connect Worcester with Providence, a major Atlantic port. Built between 1825 and 1828, the Blackstone Canal was 45 miles long, 34 feet wide, and four to six feet deep. The initial offering for the Blackstone Canal Company was oversubscribed, but after the original construction costs ran over budget, most of the initial investors earned very little as a return on their investment.

Worcester, however, reaped enormous dividends. The canal’s first years saw a dozen boats docking in Worcester each week. Both farmers and manufacturers took advantage of transportation costs that were half those of overland wagons. Initially, Rhode Island’s tidewater wharfs would supply Worcester with household staples such as flour and molasses, and industrial supplies including coal, wool, dyes and imported machinery and hardware. Boats returning from Worcester would carry local produce, cider, hay and firewood, plus textiles and apparel, combs, factory-made cotton and wool cloth, textile and farm machinery, iron castings, paper, shingles and chairs.

The exchange was somewhat lopsided, as northbound tonnage was nearly five times greater than southbound. Worcester’s “inland port” quickly became a hub for freight to other locations. Within seven years of the canal’s opening, the Boston and Worcester Railroad began service, fueling further commercial development in the city. In 1835, just four years after the first steam locomotive was demonstrated in Philadelphia (when the entire nation had only 73 miles of rail), Worcester had railroad service. Travelers could reach Boston in 3 hours and 15 minutes. In 1839, Springfield was accessible in three hours, as was Norwich, Connecticut, the following year. By 1840, national railway mileage equaled that of canals. Trains could move four times as much freight as a canal barge for the same price.

Worcester’s central location became its destiny. By 1889, trains from Worcester travelled on 13 different rail lines in every direction. A 1913 advertisement touted 200 passenger trains daily running in and out of Worcester. To this day, the city’s motto remains, “The heart of the Commonwealth.”

This expanding transportation network attracted further investment. Worcester merchant Stephen Salisbury II built shared manufacturing space, facilities that would now be called business incubators. Most of the city’s manufacturing enterprises started in these small, rented quarters. The Old Court Mills, built by Salisbury’s father sometime before 1832 along Mill Brook, at the intersection of Lincoln Square and Union Street, offered the lower-risk option to start a business by leasing factory space. The facility soon became known as “the cradle of the Worcester tool building industry.”

Salisbury was joined by other like-minded investors who built Worcester’s downtown. These included Dr. Benjamin Heywood, with a machine shop on Central Street near the Blackstone Canal, and Colonel James Estabrook and Charles Wood, with the Junction Shops on Beacon Street. Salisbury erected buildings along Union Street, Prescott Street, as well as Grove Street. Thanks to this infusion of local capital, businesses could lease the required space, grow in size and, when ready, buy the building.

In 1839, William T. Merrifield joined this group. He began constructing a series of buildings, first wooden then brick, the largest of which grew to four stories, spanning an entire downtown block. In a town with slow-moving brooks rather than rushing rivers, Merrifield overcame the limits of water power by equipping his buildings with steam engines of increasing horsepower. The Merrifield Buildings at 100 Exchange Street provided “Rooms with Power to Rent.” Small manufacturing enterprises flocked to the downtown location soon bordered by new rail lines.

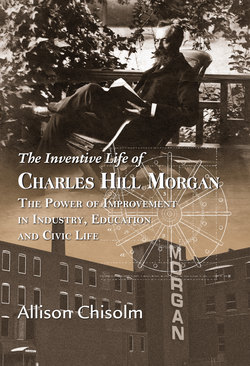

Lincoln Square, Worcester, Massachusetts, with Morgan Construction Company building visible at upper right, 1910

But the Merrifield buildings suffered a devastating fire in June 1854, one of the most destructive in Worcester’s history. Black smoke poured from the fourth floor, while street crowds looked on at the conflagration. A small daguerreotype captured the scene, one of the first examples of photojournalism. The fourth floor was out of reach for firefighters called in from surrounding towns and as far away as Nashua, New Hampshire. Buildings on adjacent streets also burned, including Merrifield’s offices, a bowling alley, church, several houses and shops, and a lumberyard. In all, the fire displaced some 50 businesses and put 1,000 people out of work. Merrifield promised tenants he would rebuild as quickly as possible, and many returned to the new building, now just three stories high.

The effect of Merrifield’s reconstructed buildings on Worcester’s economic development was widespread. Five years after the fire, the 50 tenants employed anywhere from two to 800 people each in businesses manufacturing products as varied as boot-trees, engine lathes, animal traps, sewing machines, carriage wheels and rain gutters.

The steady supply of power and the diversity of local industries were a bulwark against the series of economic downturns in the national and global economy during the 19th century. Steam engines ensured Worcester’s prosperity. In 1875, the city had 108 steam engines generating 8,000 horsepower. By contrast, its 27 waterwheels produced just 721 horsepower. Unlike mill towns that were reliant on river power and whose mills typically clustered around just a few industries, Worcester suffered little through the nineteenth century’s regular economic downturns. As late as 1913, city boosters could claim that it had “not lost a penny by a bank failure.”

As historian Kenneth Moynihan observed of Worcester’s early years, “a pattern of cooperation among creative artisans and imaginative capitalists ... would give a distinctive and long-lasting cast to its economic and civic culture.”