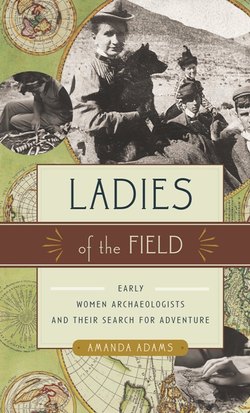

Читать книгу Ladies of the Field - Amanda Adams - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

FIELD NOTES

The first women archaeologists were Victorian era adventurers who felt most at home when farthest from it. Canvas tents were their domains, hot Middle Eastern deserts their gardens of inquiry and labor. Thanks to them, conventional ideas about feminine nature—soft, nurturing, submissive—were up-ended. The excavation shovel churned things up, flipped things over, and loosened the stays of gender a little. Ladies of the Field tells the stories of seven remarkable women, each a pioneering archaeologist, each a force of nature who possessed intellect and guts. All were convention-breaking and courageous women who burst into the halls of what was then a very young science.

For centuries, archaeology had been little more than a game of treasure hunting, a kind of cowboy science in which men traveled far and wide in search of gold and other trophies to bring home. Early archaeological exploration wasn’t much different from looting; it was the khaki-clad branch of art history that emphasized digging and acquiring (nay, stealing) the art. Yet by the mid-nineteenth century, archaeology was shaking off its antiquarian robes. Women were beginning to enter the field, sending a bright signal not just that times had begun to change but that archaeology would too. The nineteenth century was a time when more and more women began rejecting common submission to the patriarchy. It was a time of increasing social turmoil: John Stuart Mill’s book The Subjection of Women (1869) was causing a stir in its demand for equality between the sexes. Working-class girls were receiving more education than ever before, and even inventions like the typewriter and the telephone eventually helped to bring women out of the house and into the workforce, where their talents could be at least moderately appreciated. Some women were becoming more vocal about their rights and their wants. For most this meant pursuing the right to vote in their home country or the opportunity to simply further their education. For others, it meant climbing mountains, becoming doctors or architects, and fighting for entry into scientific fields. For early women archaeologists, it was by their work—some of it sensuous travelogue, more of it formidable scholarship—that they helped to reshape how we study the past.

The belief persists that women are not mentioned in the early annals of archaeology’s history because they weren’t there. Not true. Women were present in the archaeological field by the mid- to late 1800s, but they were very few and were often given diminished scholarly treatment by male colleagues. As one scholar explains, “Over the course of the last 150 years, a rigid power structure has been established in archeology. Although men have controlled this power structure throughout the history of the discipline, women have always made significant, if devalued, contributions to archeology.”1 Those neglected contributions are emerging from the shadows today.

Before the 1920s and 30s, when archaeology became more firmly established and its doors were opened to women much more so than ever before, a handful of intrepid ladies chased their love of hidden history. Some worked part-time in museums; others had the financial means to contribute to digs and explorations. But an extraordinary few packed their bags, left the floral sitting rooms and pretty petticoats behind, and embarked on rigorous journeys that took them around the world in pursuit of archaeological wonders. This book is about them.

The pioneering female archaeologists were a diverse group: reckless to some, the smartest and most laudable ladies to others. The very first to “scale the heights” of a camel and touch patent leather shoe to Egyptian sand was Amelia Edwards. Eventually nicknamed the “Godmother of Egyptology,” Edwards sailed the Nile on a houseboat as early as 1873, sketching the pyramids and eventually making an archaeological discovery all her own.

Soon after, Jane Dieulafoy burst onto the scene with her archaeologist husband, Marcel. The two of them traveled thousands of miles on pounding horseback through what is now Iran. They set their sights on the ruins of Susa, and Dieulafoy became one of the most celebrated women in Europe, not just because of her archaeological prowess, but because she was a French lady who preferred to wear men’s clothing. She even requested and obtained an official permit from the government authorities to do so.

The strong-minded Zelia Nuttall was born in San Francisco and schooled in Europe and eventually made her permanent home in Mexico City, where she became a prominent scholar in Mexican archaeology, a cultural icon in black lace shawl, and master gardener of ancient seeds. She played host to celebrities such as D.H. Lawrence and was a firm believer in modern scientific methods. Nuttall was also famous for finding ancient papers and objects the rest of the world had presumed lost.

Gertrude Bell deserves her own book, and luckily several have been written about her. A legendary lady, she was an insatiable traveler, brilliant intellectual, photographer, diplomat, strategist, and all-around “Queen of the Desert.” In Bell’s heyday, she was the most powerful woman in the British Empire. Her life soars with supreme adventure, and no matter where she was, she always wished “to gaze upon the ruins.” The pursuit of archaeology is what structured Bell’s expansive wanderings.

In her mid-twenties Harriet Boyd decided she could learn far more about ancient Greece by living there—under its blue sky and white colonnades—than by studying its history in the pages of a library book. By 1900, she was crossing the wine-dark sea to begin ground-breaking excavations at the site of Gournia on the island of Crete. Before leaving Athens she had also developed a reputation as a girl bicycle rider. Newspapers chronicled her daily exploits (even if she was just doing errands); she shocked passersby by touring through Athenian streets in a long dress on a bike with a basket.

Not long after, the world’s future best-selling novelist Agatha Christie was sitting at her rickety desk in a humble London flat typing out the draft of one of her first detective stories, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Little did Christie know that she would soon be divorced, onboard the Orient Express alone, happier than she’d ever been, and en route to meet her second husband, Max Mallowan. Together they would spend thirty years inside the trenches of archaeological fieldwork.

Last, there is the enigmatic Dorothy Garrod, a ferociously good scholar who methodically tore down what final barriers still stood that prevented women from joining the ranks of archaeology. Garrod’s quest was to discover the very origins of who we are and where we come from. Having lost three brothers to World War I, she dedicated herself to proving her own life worthy not just of one man’s accomplishments but rather of three.

All seven women were headstrong, smart, and brave. They had a taste for adventure, a kind of adventure that no longer exists today. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, massive swaths of desert remained unmapped, communication moved no faster than a horse’s gallop (at least in those deserts where they roamed; the first transatlantic telegraph wasn’t sent until the mid-1860s), and to travel at all as a woman—especially as a woman alone—elicited most people’s disapproval. Yet here were these seven women who risked everything just so they could dig in the dirt. This book sets out to discover who these extraordinary women were, what made them tick, and why they chose archaeology—a career grounded in mud, bugs, leaky tents, and toil—as their life’s consuming passion.

THE VICTORIAN ERA (1837–1901) PROVIDES THE backdrop for all seven women: each was born in or worked during that time. To be a woman archaeologist today requires some sure navigation through a boy’s club, but back then, the boy’s club was bolted shut. In Victorian times, opportunities for women outside the home were no larger than the tiny embroidery stitches the girls worked on each day. Women could and often needed to work to help support their families, but that labor typically consisted of sewing, washing, domestic service, shoemaking, and factory jobs. The upper echelons of intellectual careers and politics were largely off-limits.

Queen Victoria was in reign, and it is ironic that one of history’s most debilitating times for women, socially speaking, was when a queen ruled the Empire.2 Victorian influence on the private and public spheres of life was felt not only in England but also in France and across the Atlantic in North America. Industrialization was dramatically transforming society: the divide between rich and poor widened, and suddenly, the home and the workplace became two very different and separate spheres. Women were shooed into a domestic role, expected to become chaste “angels of the house,” cheerfully on hand to meet the needs of their husbands and children (think of a full-time domestic goddess without an exit strategy or a cocktail hour) while men engaged in the world and its affairs. Rousseau’s view on the expectations and education for a woman sum it up:

All the education of women should bear a relation to men— to please, to be useful to them—to possess their love and esteem, to educate them in childhood, to nurse them when grown up—to counsel, to console, to make their lives pleasant and sweet; such are the duties of women and should be taught to them from infancy.3

His eighteenth-century views continued to inform the next century and were frequently cited as the way to go. Females were creatures of service. Their minds should never be taxed because their brainpower was delicate and feeble. Girls were praised for their passivity and obedience, and throughout Queen Victoria’s reign (and to some extent after) women’s lives were made highly interior, almost invisible, while men assumed a greater public persona and place in the work force. It was a polarizing time of public versus private, male roles versus female roles.

Science didn’t help. Scholars gave credence to theories that women were “weak in brain and body.” They needed a man’s protection from the world. Doctors proclaimed that “love of home, of children, and of domestic duties are the only passions they [women] feel,”4 that “a reasonable woman should always be contented with what her husband is able to do and should never demand more,”5 and perhaps most damning, that “any strain upon a girl’s intellect is to be dreaded, and any attempt to bring women into competition with men can scarcely escape failure.”6 How the first women archaeologists defied the times! With dirt under their fingernails, living in tents, managing large crews of male workmen, attending universities, smoking men’s pipes, wearing trousers, some never married, some never mothers—all were deliciously defiant of the social roles pressed upon them.

These seven foremothers of “inappropriate” behavior blazed a trail that helped other women enter the world and the work of science, but these pioneers also reached even further. Newspaper articles and monthly magazines carried stories of their adventures and accomplishments. Public speaking tours brought thousands to hear them. Slowly, but most surely, they reconfigured the public impression of a woman’s worth and dismantled the building blocks of unchecked chauvinism. It was through the seemingly “masculine” work of archaeology—the physical labor, discomforts of the field, the dirt and discovery—that these women helped to revolutionize the very nature of womanhood, or, perhaps more accurately, our understanding of woman’s nature. Although actions to address gender inequality had already been stirred in the mid-nineteenth century—rumblings of Britain’s women’s suffrage movement began in 1866—it was the first women archaeologists who chipped away at the foundations and rationalizations of Victorian age thinking with real tools: steel shovels and excavation picks.

Each woman described here made a significant contribution to archaeology when it was just a fledgling science, but they also illuminate the myriad facets of a woman’s world. Some sought adventure and made the world feel bigger; others were drawn to mystery. One worked within a life-long partnership, and another in pure solitude with stingingly clear fast winds at her back. In a letter home to her father, Gertude Bell once exclaimed while traveling alone on horseback through the desert, “How big the world is, how big and how wonderful.”7 The world is big and wonderful, and these women embody the very best of its possibility.

Each chapter tells one woman’s story and explores why she chose archaeology as her life’s purpose. Did these women find a much bigger and perhaps more wonderful world in the fields of archaeology than they could ever have at home? Did they forsake romantic love for this world? Did they live with any regret? Were these seven women happy in their chosen career, one that afforded them terrific adventures but always required a relentless uphill climb, both literally and metaphorically? And as any archaeologist would want to know, what exactly did these unique women find along the way?

Seven women; surely there must have been more. Many woman worked along the margins of archaeology during the Victorian era and for the next decade or two afterwards. Some of these women, like Sophia Schliemann and Hilda Petrie, were the wives of famous archaeologists. They worked alongside their husbands in the field and no doubt knew their stuff, but the record they left behind is as faint as old carvings on weathered stone. They never published on their own (or not much), and their labor in the field lacked real ownership or autonomy. For better or worse, as those wedding vows pronounced, they were wives to their men, and those men authored the reports, led the teams, and took full credit for any discoveries of note. Wives in the field were viewed as extremely useful assistants. They could draw artifacts, keep the lab in order, inventory artifacts, and nurse the wounded field crew, but true scientists they were not. At least not as recorded.

ABOVE : Sophie Schliemann, wife of archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, wearing the jewels of Helen of Troy, 1876

Archaeology thus has several ghosts. For many of the first women who worked in the field, there was no afterlife—no legacy. Their work wasn’t registered in the pages of history. The earliest contributions of women in the field are in the style of the man behind the man, or more aptly put, the woman behind her husband, the mere whisper in an ear at night before bedtime.

There are also other women who contributed to archaeology but who are not included in this book for one of two reasons. First, Ladies of the Field is not intended to be an encyclopedic account of every female who in one form or another engaged with archaeology during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. That would be a different kind of book—more a compilation of names and dates than a series of inspiring stories. Women such as Margaret Murray (1863–1963) who taught archaeology in the classroom more than they excavated in the field are not included here. Some women archaeologists, such as Edith Hall, were students of other earlier women archaeologists—in Hall’s case, Harriet Boyd Hawes. Hence, some women’s careers and contributions are folded into relevant chapters.

Second, some exceptional women archaeologists, such as Kathleen Kenyon (1906–1978), famous for her excavations at Jericho and first woman president of the Oxford Archaeological Society; Russia-born Tatiana Avenirovna Proskouriakoff (1909–1985), who conducted breakthrough work on Mayan hieroglyphics; and even the German mathematician Maria Reiche (1903–1998), who spent her life surveying geoglyphs called the Nasca Lines in the Peruvian desert—all make their debuts just slightly after the period highlighted in this book: the Victorian era. Their lives and work are of great interest, but it was the earlier pioneers, the seven women discussed in chapters to follow, who paved their way.

The intent here is not to exclude (that has happened often enough to women’s work throughout history) but rather to sharpen focus on seven lives that reveal much about early archaeology and what it took for women, in general, to become a part of it. The women presented here may have not been the very first to kick a shovel into the ground, but they were the first pioneering and fearless women who set upon archaeological research forcefully, unconventionally, and most of all, on their own terms. They worked in the field, excavating by themselves or in the company of hired teams and other female colleagues. They supervised ground-breaking excavations and made lasting contributions to archaeology as a growing science. Jane Dieulafoy and Agatha Christie worked alongside their husbands, but both enjoyed an uncommon degree of latitude in pursuing their own scholarly interests and were given credit for their expertise. Instead of “assistants,” Dieulafoy and Christie were viewed by their spouses as true and equal partners.

Edwards, Bell, Christie, and Garrod were British; Dieulafoy, French; and Nuttall and Boyd Hawes, American. It’s a Western team. Not one of the women presented here heralds from Asia or India, Africa or South America. That is because archaeology was born of Western science. It moved with spreading colonialism, was a tool of the British Empire, and fascinated the Western mind with its growing toolkit of physical evidence, theories, documentation, accurate measurements, hypothesizing, and overall propensity for logical explanation. This was a new way to interpret the past. The founders of archaeology were all of a Western European, and by extension, American mindset. It would be some time before other parts of the world began to systematically excavate their own backyards for history’s buried remains.

In addition, the women chronicled here have all left handsome paper trails. Their journals, field notebooks, photographs, letters, diary entries, and publications allow a researcher to immerse herself in each woman’s own historical context and tap into her spirit. It’s the women who wrote enough to reveal themselves— their ambitions, frustrations, inspirations, and doubts—who made their way into this book. Based on the artifacts each woman left behind, could a pioneer and her legacy be brought into clear and compelling focus? Seven could, and these are the trendsetters who rode out into wide-open spaces, on horseback, donkey, or camel’s hump, without precedent and against all odds to find what they were looking for.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELD—DESERT dunes, riverbanks, crumbling ruins, and buried tombs—still exudes magnetism today. The romance of archaeology persists, and one has only to hum the tune of Raiders of the Lost Ark (duh-duh-duh-DUH! da-da-da!) and a scene of sweaty, dangerous adventure and jungle glory is unleashed. Yet aside from popular caricatures of archaeology, the passion for understanding human history—and more to the point, the story of what makes us human—is a quest that continually fascinates.

Sunken ships littered with skeletons and chandeliers, the fossilized footprints of an ancient ancestor in Africa, a bone amulet—these are the kinds of things archaeologists may find. Drawn to the tantalizing possibility that an ancient city, a site, or an artifact might be discovered that could change everything we thought we knew, we wait to see what comes next. Could there be a lost library containing thousands of books in a language never seen before? Perhaps a new link in the evolutionary chain of our species, a link with a wing nub instead of a shoulder blade? What if we find a buried wooden boat preserved in a bog that dates so far back that all the theories of human migration to the New World will need to be rewritten? Archaeology is uniquely, and consistently, able to renew and sometimes redefine our understanding of ourselves.

As Amelia Edwards remarked in 1842, archaeology is that subject where “the interest never flags—the subject never stales—the mine is never exhausted.”8 Archaeology never stales because it keeps reinventing the big story of us.

The archaeological field is a centerpiece to each pioneer’s story. Each woman found her way to some very out of the way places, circa 1900, in the name of her research and study: Iraq, Iran, Crete, Morocco, Palestine, Syria, Gibraltar, Mexico. Often the field called to her with its own type of siren’s song, a tune mingling mysteries of earth and history on a breeze. Today the field continues to beckon adventurous souls curious about where we’ve been and where we’re going. The study of the past is nearly universal, and although each culture has a unique way of embracing and explaining its own history, archaeologists are a self-selecting crowd. They have their own particular, even peculiar toolkit and a strong desire to dig for history’s precious leftovers.

LEFT: Necklace, bracelets, and fragment of decorated pottery

RIGHT: Earthenware vessel and stone artifacts

Before the skies were filled with airplanes that could get you there and back, archaeology meant going off into strange places with only what a team could carry. Archaeologists would leave in search of something that might lie hidden beneath piles of dirt. Shovel in hand, they would chase that dream of discovery, becoming crazed and toilsome if it wasn’t found, brilliant and celebrated if it was. Despite its glamorous image, archaeology is hard work: dirty, muddy, sand-in-your-eyes, exhausting, inconvenient, and on occasion boring work. Not everyone’s cup of tea, especially in the days of Victorian England when sipping tea was exactly what a lady was supposed to be doing.

Yet when they returned from the field, it was beyond dispute that the first women archaeologists had held their own physically and intellectually in what was then a man’s world. They had traveled, dug, scrutinized sites, managed, and made it. Impressive. So impressive that these women are sometimes in danger of being transformed into myth. Although I have boundless admiration for each of the women chronicled here, I try to avoid giving in to pure romanticism. The greatest honor is in keeping it honest. When you are working in the field you want your notes to be as accurate as possible, your maps as precise as can be, so that your reconstructions and interpretations are reliable. I aim for the same here. Legends can become the stuff of make-believe, overshadowing the realities and nuances of a true life.

These early archaeologists were never camelback saints (and they would be dull if they were). They were products of their time and made choices that by today’s standards would elicit criticism and might even be judged as politically incorrect. In some cases they chose to play very much in a man’s world and occasionally viewed other women, in popular patriarchal fashion, as dithering inferiors instead of comrades. They present sometimes frustrating contradictions that both support and undermine a feminist view. Complex individuals, they challenge us, as they once challenged their own peers and colleagues, to take them as they are.

With that in mind I ceremoniously opened an old archaeological field-journal of mine one breezy bayside day in northern California and invited the ladies in. Come on down, drink coffee with me, spread your old maps out on my desk, and let’s make a book together. I asked them into my small studio, encouraged them to kick their dusty boots up onto the kitchen table. Remind me of your crazy lives and courage. I asked each of them to look over my shoulder as I wrote their respective chapters, and if that didn’t make the writing any better, it did make my own journey through their stories richer.

Archaeology’s essence is to uncover the origins of things, the epicenters of change, the evolution of style, technology, and everything else that makes us human. It makes sense that these pioneering women would take such a field of study as their own. As they challenged ideas about what a woman could accomplish, transformed styles of clothing through cross-dressing, cut their hair boyishly short, and broke into a scientific field previously denied them, little did the ladies know to what extent they were making history themselves.

ABOVE : Amelia Edwards, the revered godmother of Egyptology