Читать книгу Ladies of the Field - Amanda Adams - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1851–1916

JANE DI EUL A FOY

ALL DRESSED UP In a Man’s Suit

Hair cropped mannishly short, a board strapped beneath her white linen shirt, and a red ribbon looped through the buttonhole of her well-cut suit jacket, Jane Dieulafoy embraced la vie de l’homme. In a day when new brides were expected to tuck into homemaking, to fluff the nest and prepare for babies to arrive, the Dieulafoys began their marriage in a radically different way. Shortly after their wedding, Jane Dieulafoy dressed herself convincingly as a boy and fought as a front-line solider alongside her husband, Marcel, during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870. She camped with the men, never revealing her identity as a woman, and trekked with the army of the Loire through harsh conditions and definite danger.

Later, as her interest in archaeology blossomed and her explorations in the field took her to what is now Iran, she adopted the dress of a western man completely. Forsaking the ruffled petticoat, Dieulafoy was one of the first European women to slip into a pair of pants. In doing so she became something of celebrity in nineteenth-century Paris where she was both admired and mocked. She never went back to women’s clothing. Her cross-dressing had something of a Charlie Chaplin effect; she looked a touch comic in pictures and sketches yet completely put together and fashionable, her shirt buttoned high up her neck, waistcoat snug, trousers perfectly tailored, black shoes laced and polished.

Through her writings, personal and published, it’s evident that Dieulafoy was bored by Victorian society. She longed to “pass the days and ease the burden”1 of the bourgeois life she was born into, and only upon returning from exhausting field excavations did she allow herself to be fêted by salon society. Hardships of the field were washed away with disinfectant soap and champagne, while the artifacts she and Marcel acquired abroad significantly enriched the collections of the Louvre Museum. Perhaps one of their most famous finds, the Lion Frieze at Susa, spurred both public wonder and long ticket lines. Its discovery was something of a miracle after weeks of bad weather and poor luck.

When she wasn’t on site, Dieulafoy was a prolific travel writer. By virtue of her pen, she was able to leave Parisian life and daily humdrum to roam desert dunes and ancient tells again. She invited the men and women of France to join her on those journeys, bringing the exoticism of the Orient and the feel of camelback sojourns into their reading rooms. Her life of adventure is what led the New York Times to refer to her as the lady “regarded as the most remarkable woman in France and perhaps in all of Europe.”2

Tough, strong-willed, highly singular, Dieulafoy was by her own definition a “collaborateur” with her archaeologist husband, Marcel. She deliberately chose the masculine form of the French word to convey her meaning. No “la” here. Yet what was there was . . . l’amour.

Almost as fascinating as Dieulafoy’s unorthodox way of life was her marriage. The relationship she and Marcel formed was built on professional respect, partnership, equality, and affection in a time when these qualities were rare in a marriage. Dieulafoy reminds us that being an accomplished and daring woman in her time didn’t require a dismissal of the other half. A woman could be a daredevil and married. For unlike some of the other pioneers in this book, she found an outlet for her explorations, intellect, and professional pursuits as a highly regarded and beloved partner.3 Marcel publicly acknowledged her work and her partnership when most women and their contributions, scientific and otherwise, were greeted with silence or at best a slight mention. Even today’s feminist scholars acknowledge that the Dieulafoys had something special going on.

Jane Dieulafoy was a commendable archaeologist and a real first in the field. Her crews, all men, numbered in the hundreds, and she often oversaw them by herself. Beneath desert skies, inland and away from water, having suffered months of sterile digging—where each shovelful of dirt comes up empty, high hopes for a find decrease, and motivation weakens—Dieulafoy remained steadfastly devoted to her purpose. More than a treasure-hunter, she was very much the burgeoning scientist with a clear objective: the site of Susa. Monitoring the excavation trenches, devising field methods when there were few to none established, and meticulously mapping, labeling, and reconstructing what was discovered, Dieulafoy gave archaeology a good name. She gave “woman” a good name too, even if it was all dressed up in a man’s suit.

JANE DIEULAFOY WAS born Jane Henriette Magre in Toulouse on July 29, 1851. Her parents were well off, a family of bourgeoisie merchants that owned two countryside properties where Dieulafoy grew up as a “small, slender and blond” girl who “lacked neither grace nor charm.”4 Dieulafoy’s father died when she was very young, and she and her five siblings grew up under the care of their mother. Jane was bright and intelligent, a girl described as both mocking and affectionate. She was possessed of a quick wit and was already marching to a different beat from that of most little girls her age. Dieulafoy’s mother enrolled her daughter in a convent, the Couvent de l’Assomption d’Auteuil in Paris, at age eleven so that she would have an above-average education. There she was instructed by the sisters in Latin and Greek and lived a life of very strict routine and schedule: early mornings, prayers before breakfast, cleaning, studying, more prayers, bedtime. She didn’t rebel against this routine but, as she did for all of her life, accepted the very conventional conditions and even adhered to them with gusto and conviction. Yet she still managed to turn every assumption and rule on its head.

She stayed at the convent until she was nineteen years old and, a little surprisingly given her nonconformist stance on most matters later on, moved straight into marriage. Her charms, and a “face always crinkled in a smile,”5 caught hold of Marcel Dieulafoy’s heart. Marcel was a well-traveled young man, an engineer who specialized in railways, and he had a handsome face tanned by travels in Africa. Like Jane’s, his family also lived in Toulouse. Both families were well off, influential, and likely acquainted. From the cool confines of the convent, with its musty books and pursuits in spiritual atonement, Dieulafoy must have been gripped with excitement to meet a man who promised so much in the way of warmth and new direction. He was the open door to both opportunity and the Orient. She accepted his marriage proposal quickly, and thus began a life of partnership that would last forty-six years—until death did make them part.

Schooling complete, a comfortable marriage at just the right age, Dieulafoy moved through society smoothly and appropriately, with little upset. But with Marcel now by her side, the two jointly threw open the doors of life and considered a scene of vast possibility. Dieulafoy was powerfully committed to Marcel, not so much as a “wife” in the traditional Victorian sense of service and submission, but as a fiery life partner. As was Marcel to her. And they would make the very most of life.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, when French forces began to buckle under the power of the Prussians and enemy ranks laid siege around the very walls of Paris, Marcel became furious. He requested active service (no draft or obligation to military service was in place) and was enlisted as a captain in command of troops based in the town lyrically named Nevers. When he went to war, Dieulafoy did too. A bride of barely twenty, she donned her first pair of gray trousers and a soldier’s overcoat, disguising herself as a boy—a clean-shaven sharpshooter, to be exact.

Women were only allowed to join the army as canteen workers. They dished food and filled water cups. Whether it was for love of Marcel or for an equally passionate drive to protect her motherland, Dieulafoy didn’t hesitate to choose the rifle over a soup ladle and become a warrior. She and Marcel endured a terrible winter together of marches, hunger, and exhaustion. Although cheered by their comrades’ acts of heroism, they were depleted, emotionally and physically, by the grisly horrors of war. Their bizarre honeymoon was spent on the violent frontlines. When it was over the Dieulafoys returned home, discouraged because their effort had not been victorious, but back in Toulouse they resumed a relatively normal life. Marcel went back to work, and Dieulafoy likely buttoned herself back into petticoats.

Domestic stability was nothing either craved, however. They were both intrigued by the exotic lands of the East; for Marcel they held special architectural interest. He believed that Western medieval architecture had its roots in the ornate styles found in the ancient mosques and buildings of the Orient, and his quest to prove this supposition began to define his chief interests. He wasn’t an archaeologist by training, but he was by nature. The Dieulafoys left France every year for trips to Egypt and Morocco, where they traced architectural influences and began to knit their passion for travel and historical research together. By 1880 they were preparing for their biggest adventure yet: Persia. This was where Dieulafoy said her husband would seek “the link which connects Oriental art with that of Gothic art,” the phenomenon that, “sprang so suddenly in the Middle Ages . . .”6

MEN’S CLOTHES WERE comfortable, pants were much better than skirts, and boots and overcoats were much more practical than dainty shoes and lacy gloves. After growing fond of men’s attire during the war, Dieulafoy probably didn’t even bother to pack a dress for Persia. An article from 1894 describes the Dieulafoys as a couple who “agree that a common dress enables man and wife to submit to the same conditions and share the same pursuits. One can go where the other goes in bad weather. Vicissitudes of travel and arbitrary social rules that make distinctions for petticoats are effaced. It permits an unbroken companionship. It makes possible one life where there are two lives.”7

United by love and two pairs of trousers, Jane and Marcel spent a full year planning for their excursion to Persia, a trip that would last nearly twenty-four months. They departed in 1881, and upon arrival in Persia they started to travel by horseback, carrying bags filled with photography equipment: cameras, glass plates, chemicals, and such. They also carried weapons. Two westerners— seemingly two men by anyone’s quick glance—without escort were very vulnerable to attack from unfriendly strangers.

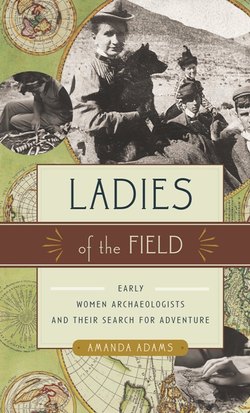

ABOVE : Jane Dieulafoy, age thirty, dressed for travel and hard work in the field

The Dieulafoys traveled an extraordinary 3,700 miles in the saddle between 1881 and 1882.8As they moved across the landscape, they systematically documented and photographed old buildings along the way, creating a treasure trove of reference material for generations of future historians and archaeologists. Their “unbroken companionship” was put to a test that would sink many couples. There were days of pummeling rain, bad fevers all around, nights spent sleeping on rocky floors, stretched financial resources, and, for Jane Dieulafoy, a head full of lice and hair that she had to continually shave. Her blond locks gone, she looked just like a young man, “a rifle on her shoulder and a whip in her hand,” and one of her biographers explains that “she fooled everyone, from robbers on the highways to the shah himself, who did not want to believe her when she revealed her actual gender.”9

LEFT: Ancient glassware recovered intact from an archaeological site

RIGHT:Ornately carved spoons and ceramic bowls

Throughout their travels the goal was always a remote and legendary place called Susa. Situated at a distance east of the Tigris River, the Susa region was home to an ancient city that had already undergone some cursory excavation years before. The Dieulafoys knew that its potential was great, and they wanted to have a hand in uncovering the ruins. All of that would come later though.

Their journey to Susa was strenuous, and both were sick and worn down by the time they arrived in a deluge of heavy rain. After nonstop travel, saddle burn, and months of camping, they must have craved a clean, comfortable bed. Perhaps even some croissants and a current copy of Le Tour du Monde. Having made the acquaintance of Susa, they left knowing that they would be back. Dieulafoy wrote in her notebook, “The souvenir of Susa haunted my husband in his sleep.”10

SUSA WAS AN ancient town surrounded by what was then a widespread emptiness: “. . . there is not a single habitation to enliven the landscape. Some nomad Persians and Arabs camp in this vast solitude, and live wild and savage on the milk of their herds, or on the fruits of plundering raids,”11 explained Jane through her nineteenth-century looking glass. As a royal city, Susa once exerted an influence greater than that of Babylon, and it was a town of “radiant focus” where artists from as far away as Greece would gather, flourish, create.

When the Dieulafoys returned to Susa in 1884—now on site to properly excavate and with all permissions secured as well as a formal team to begin work—they stood before an artificial mountain and a series of hills technically known as “tells.” It was a landmass created by thousands of years of earth and wind quietly cooperating to bury a city. Crumbling palace towers were peaks, and ancient roads had become low valleys where “wild cats and boars” roamed. Dieulafoy was bursting with happiness at their arrival: “The weather was rainy; our tents let in the moisture; provisions were short; our soup cooked in the open air, was better provided with rain water than with butter; nevertheless we were joyous—joyous because we had reached Susa, joyous because we had taken possession of the site which we had so long aspired to excavate.”12

The team unloaded their pickaxes, buckets, and tools and then, with enthusiasm still pouncing, faced three small dilemmas: the first, where to start? Choosing where the first trench should go was like opening the pages of a coverless book, hoping it was the one you wanted in a library’s line up of thousands. Would they plant their shovel right? Find something fast, or sift sand that contained nothing at all? Second, they had no workmen and they would need scores. And third, everything they excavated was under the watchful eye of locals who believed, perhaps rightfully so, that the artifacts belonged to them, not the Dieulafoys. The dunes were alive with these looters in search of golden relics, and come nightfall they would try to raid the site.

In deciding where to start, the team considered the work of excavations conducted thirty years earlier by two British men. Based on their preliminary findings, the Dieulafoys had a rough sense of where column bases and even a helpful inscription or two were located. The team decided to take their chances and excavate three tells all at once. These consisted of a throne room, the citadel, and a private residence called the “King of Kings.”13

With the massive digging task before them, they turned to the locals for help in recruiting a veritable army of workers. In her notes, Jane laughs at the process whereby “an old Arab, whose only nourishment consisted of the herbs which he browsed on the tumulus [an archaeological mound, or tell], a poor devil who had been robbed by the nomads, and the son of a widow who was dying of starvation in the Gabee, were at last enrolled at fancy prices . . . Marcel and myself took command of this glorious battalion.”14 It was a modest start, but the ranks of their field crew would eventually swell to more than three hundred men.

News of the excavations carried far and wide, and eventually their biggest headache was too much help. Crowds of men wanted to work the trenches. Every morning at the crack of dawn they would surge to the site, spades in hands, and if not put to use and given a day’s wage, they became surly and tried to “pillage the tents.” Once a desolate spot in the desert, the Dieulafoys had transformed Susa into a hub of swarming bodies—shoveling, sweating, and sorting.

As for the nightly danger of looters, that was solved simply: firearms. Armed watchmen were installed around the site and paid a fee more lucrative than theft. It was with all this in place that Jane Dieulafoy stood up tall, walked to the trench, and grabbed hold of her tools for the first breaking of ground (a little like smashing a champagne bottle in celebratory spirit). She captures the moment: “Full of emotion, I struck the first blow with the pick on the Achaemenidaen tumulus, and worked until my strength gave out . . . this was how the excavations at Susa were begun.”15

The trenches grew deep quickly, but they were achingly empty. Fourteen feet of nothing. A few funeral urns were found here and there, each with a skeleton curled up inside, but aside from that the dirt was barren. Rain continued to pour, and the team stood mired in tacky mud, working long hours all day with only two things to look forward to: a wet tent and hope for tomorrow’s discovery. This was the stuff of typical field archaeology. For each day of glory and spectacular finds there are long weeks— and sometimes entire seasons—of toil and tedium.

Luckily for the team, Dieulafoy soon had cause to shout, “Heaven be praised!”

One of the workmen had scraped the surface of some bricks glazed in colorful enamel. The workers redirected the trenches and opened them wide: two hundred feet long and twenty-six feet across. A month of careful excavation followed, and they were rewarded with the find of a lifetime: the Lion Frieze. They assembled this ancient masterpiece, fragment by bright fragment, on the floor of their tent. It was by Dieulafoy’s own account “magnificent,” with each lion measuring more than eleven feet long. Dieulafoy wrote of her find: “The animal stands out against a turquoise blue background; the body is white, the head surrounded by a sort of green victorine, the mustache blue and yellow, the flanks white, the belly blue. In spite of its extravagant coloration the beast has a terribly ferocious aspect.”16

The Lion Frieze ushered in a new pace of discovery. Soon there was an opal seal in Dieulafoy’s hand that belonged to Xerxes the Great, along with carved ivory, spear heads, bottles, bronze and terra-cotta lamps, engraved stones, coins, funeral urns, and a “thousand interesting utensils.” A life-size painting of a black man in rich robes was revealed and left the crew to ponder whether they were in the company of the ancient Ethiopians Homer once spoke of. In fact, much of what they uncovered let their minds run with theories and speculation about the ancient world. This was not a single dwelling or cave they were exploring; it was a cultural epicenter, a whole city. The Dieulafoys and team scraped away all they could to shine a light on the region’s sprawling past.

MIDWAY THROUGH THE excavations at Susa the Dieulafoys had accumulated so much cargo that they had to figure out how to transport it out of the country. There were fifty-four wooden boxes filled to the brim, and everything that didn’t fit in those was buried by night in a secret spot known only to the Dieulafoys.17Anxious to avoid a two-hundred-mile-long journey through a country where the objects they had collected were viewed as “belonging of the prophet” and therefore “treasures and talismans” that the locals would (naturally) want back, they made a dash for Turkey. An etching titled “Transporting Treasures Across The Jungle From Susa To The Persian Gulf” depicts seventeen villagers heaving a single cargo box through tall grass by rope. Their effort wasn’t helped by two men in pith helmets (or could it be Jane sitting beside Marcel?) who sat lounging on top of the cargo the workers were shouldering.18