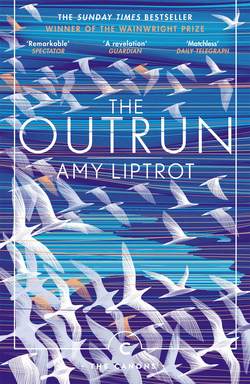

Читать книгу The Outrun - Amy Liptrot - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

TREMORS

WHEN I GET BACK FROM my walk on the Outrun, instead of entering the farmhouse I go to the machinery paddock and open the door to the caravan where Dad now lives. The sheepdog waits outside for him and the horses have their heads over the gate, looking for hay. The old caravan is weighted down with concrete blocks against the wind. One of the windows was blown out in a gale last winter and has been patched up with a wooden sheet.

Inside, Dad is wearing his outdoor boiler suit, with baler twine and a penknife always in the pockets, over a jumper that Mum knitted, which he still wears, now patched at the elbows. He’s sitting in the upholstered corner seat with the best view out through the large Perspex window, across the farmyard and fields, over the bay to a headland. The colours of the sky and the light on the sea change all day as rapid Atlantic weather systems pass over. When the clouds break, sunlight dazzles on the water. An outcrop of rock is exposed at low tides. Sometimes the light picks out in fine detail the hills of Hoy, another island to the south beyond the headland, and on other days they disappear completely in the haar.

In a shaft of winter sun, the air is dusty with muck from outside and smoke from the roll-ups Dad smokes. There are outdoor clothes and wellies by the door, farm paperwork spread over the low table, and the glow of a gas fire. At the other end of the caravan is a bedroom and the dog sleeps directly below Dad, under the caravan, like a wolf in its cave.

‘Did you feel anything up there?’ Dad asks, before beginning to tell me, although I’ve heard it before, about the tremors. This stretch of cliffs and beaches, where the mythical Mester Muckle Stoorworm is first said to have made himself known, where the people of Skara Brae eked out their lives and where HMS Hampshire was sunk, has mysteries.

Some people on the west coast of Orkney, including Dad, say they experience tremors or booms sometimes, low echoes that seem strong enough to vibrate the whole island while at the same time being quiet enough to make them wonder if they imagined it. ‘You hardly hear it, but feel it more,’ says Dad. ‘It’s a low-grade boom, like thunder at a distance. There are vibrations of the ground enough to shake windows and shelves. It lasts for one pulse and is often repeated a few times in a couple of hours.’ Locals say they have felt the booms over many years but are unable to identify a pattern to their occurrence. They wonder if it is geographical, man-made, even supernatural – or if it happens at all.

To understand the tremors I have to look deep within Orkney’s topography. The geology of the West Mainland coast, with high cliffs at Marwick, Yesnaby and Hoy, strewn with the sea stacks, sloping rocks and treacherous currents responsible for many shipwrecks, is the first place to look. It is possible that the booms and tremors are caused by wave action within caves deep below the fields. As a large wave travels into a dead-end cave, it traps and compresses air at high pressure. When the wave retreats, the air bubble explodes, causing a boom.

Others blame the tremors on the military, and sonic booms produced by jet aircraft. Around sixty miles from Orkney, on mainland Scotland, the Cape Wrath Ministry of Defence range is where the military train on and offshore. This sparsely populated area is one of the few places in the UK where the ‘big stuff’ can be detonated. Heavy air weapons would be the only thing that could send a sonic wave as far as Orkney but wind conditions would have to be perfect. High-speed aircraft can also cause sonic booms as, on dive-bombing runs, they descend into denser air, but although Dad sometimes sees and hears the planes, he says the tremors do not come at the same time. I wonder if other, harder to grasp, even ghostly, island forces could be at play. The legend of Assipattle and the Mester Muckle Stoorworm tells of a huge sea monster, so large it could wrap its body around the world and destroy cities with a flick of its tongue. A layabout called Assipattle dreamed of saving the world and got his chance when he killed the Stoorworm by stuffing a burning peat into its liver, cooking it slowly from the inside. Writhing in agony, the Stoorworm thrashed its head, knocking out hundreds of its teeth, which formed the islands of Orkney, Shetland and the Faroes. Dragging itself to the edge of the earth, it curled up and died, its smouldering body becoming Iceland – a country full of hot springs, geysers and volcanoes. That liver is still burning so maybe the Stoorworm isn’t dead at all. A tentacle may still be twitching around these shores and the tremors may be the aftershocks of the monster’s death-throes.

Talking to Dad about the tremors, I feel slightly nervous. Our conversations are normally limited to the farm – what jobs need to be done or the condition of the sheep and the land – so hearing him speak about uncanny sensations and strange geology makes me concerned that he might be getting high. Mum taught me to look for the signs. At first it could be exciting, with Dad talking a lot, full of optimism and energy, but this would bubble over into his making impulsive purchases, such as expensive rams or farm equipment, staying up all night and moving animals at four in the morning, then grandiose thoughts, with him feeling he could change time and control the weather.

On the floor of the caravan there’s a stool I remember from the farmhouse that Dad made in the hospital when he was a teenager. He was fifteen when he was first diagnosed with manic depression, now known as bipolar disorder, and schizophrenic tendencies. Since then, periodically, he has ups and downs of varying amplitude. Our family life was rocked by the waves of life at its extremes, by the cycles of manic depression. As well as the incidents with sectioning and straitjackets, followed by time away in a psychiatric hospital, there were months when he stayed in bed without saying a word. Today Dad is buoyant but, on other occasions, if he’s subdued, I worry it may signal the beginning of a period of depression and one of his long winters of inactivity.

Once, when I was about eleven, Dad was so ill that he went round the farmhouse smashing all the windows one by one. The wind flew through the rooms, whisking my schoolwork from my desk. When the doctor arrived with tranquillisers, followed by the police and an ambulance, I yelled at them to go away. He’d been taken by something beyond his control. As the sedatives kicked in, I crouched with my father in a corner of my bedroom, sharing a banana. ‘You are my girl,’ he said.

The rumblings of mental illness under my life were amplified by the presence of my mother’s extreme religion and by the landscape I was born into, the continual, perceptible crashing of the sea at the edges. I read about the ‘shoaling process’ – how waves increase in height, then break as they reach shallower water near the shore. Energy never expires. The energy of waves, carried across the ocean, changes into noise and heat and vibrations that are absorbed into the land and passed through the generations.

Since his teens, Dad has been treated on fifty-six occasions with electroconvulsive therapy. Used in the most severe cases of mental illness, an electric shock is passed into the brain to induce a seizure. No one quite knows how or why it works but patients often report feeling better afterwards, at least temporarily.

Ripples were set off the day I was born, and although I moved far away, the seizures I began to experience as my drinking escalated felt as if the tremors had caught up with me too. In lonely London bedrooms or in toilets at nightclubs, my wrists and jaw would freeze and my limbs wouldn’t respond as usual. The alcohol I’d been pouring into myself for years was like the repeated action of the waves on the cliffs and it was beginning to cause physical damage. Something was crumbling deep within my nervous system and shook my body in powerful pulses to the extent that I was frozen and drooling, until they eased off enough for me to pour another drink or rejoin the party.