Читать книгу Japan Country Living - Amy Sylvester Katoh - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCOUNTRY WAYS

LIVING IN THE COUNTRY

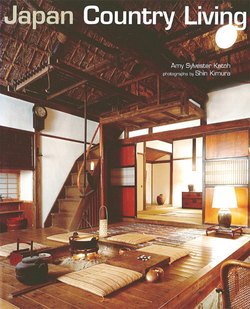

Over the years I have been invited into and have had the chance to see the interiors of those wonderful Japanese thatched houses, which have so much appeal viewed from the roadside, tucked up against mountains at the edge of a valley's rice fields. Such houses have a life and character of their own. They speak to you immediately upon entering.

One unforgettable house was on a road in the middle of the Noto Peninsula. My friends and I caught sight of a noble roof soaring above the road. We walked up the hill and found that the house was even more impressive than it had seemed from below. The architecture commanded our attention, a rare and precious token of the past. The lady of the house was just stepping out of the barn, a purple crocheted sweater over her apron, and when we asked if we could look around, she smiled with a mixture of embarrassment and surprise, saying that it was old and dirty and we wouldn't be interested. But secretly she seemed pleased at our interest in her family compound, where she had lived all her married life. She quickly darted inside and alerted her husband, who, when he appeared, was frailer and older than she and had simply put a thick jacket over his pajamas to greet us. Both happily showed us their house and outbuildings and told us some of its history. The main structure was built 350 years ago, a massive fortress against snow and cold, which once was considerable. Some parts had been added, other parts restored. Up until forty years ago, the roof was thatched, but when that proved to be too much to keep up, they converted to a tile roof. The open courtyard from where we viewed the house was fronted by the main building, clearly the living quarters. Persimmons drying on cords festooned one wall. Small, hot red peppers were drying, too, and onions from the garden. Tools of the years and ladders were hung against the storehouse.

The elderly couple was somewhat taken aback by our unbridled rapture for their house. They had some ambivalence as to the value of preserving old houses. To some extent, it implies that one does not have enough money to rebuild something new and modern and convenient. Old and dirty are synonymous, and anyone who still lives in an old house is considered dirty and probably poor. Family reputation is involved. These two will continue to keep this house going as long as they can, but they are old. What will happen when they die? Who will carry on? Will the next generation be content to live in this relatively inconvenient way?

We, outsiders who have come from cities and from other countries, gasp at this massive and handsome piece of Japan's country heritage, and urge its owners to preserve and treasure the house and the lifestyle as they have the persimmons so painstakingly hung from the rafters.

Another thrilling moment was on a trip through Miyama-cho, one of the remotest parts of Kyoto Prefecture, during the preparation of this book. We were honored by an unusual sight-a group of thatchers repairing the roof of a farmhouse. Like a woman lifting her skirts, the cover of the house had been raised and removed, and the supporting rafters were visible, spread at the base and tied together at the top. Smoky bamboo poles were being lashed on horizontally across the rafters, and thatch was being attached to them, stitched with a fat wooden needle and twisted straw twine. The beams and rafters were tied together with bindings of rice-straw rope. The village was made up of thatched houses, their distinctive straw bonnets dotting the land. I was amazed again at how utterly basic it all is-the structures, the materials, the landscape-and how incomparably beautiful.

In a changing world, traditional values break down and are replaced by new values of comfort, privacy, and consumerism. Country farms no longer support extended farm families, so men seek work in the cities and leave traditional country villages empty. Sons and daughters follow. Houses lie vacant and soon start to return to the earth from which they came, or are quickly dispatched with chainsaw and bulldozer and carted off to a local dump. I find myself searching in quiet desperation for these old friends, which seem to have been there until very recently. Gradually they fall into disuse, and a new plastic replacement is built. This is thought to be beautiful because it is clean (which is the same word as beautiful in the Japanese language). Clean it may be, but not satisfying, and its "beauty" will fade quickly, since it lacks the inner beauty and honesty of structure and material of its predecessors.

The question of heritage remains. What is it? How do we treat it? How does it fit in our lives? The easiest way is to tear old things down and replace them with the fashion of the moment. Clean, quick and cheap. In Japan, prefabricated houses replace structures built to last for centuries. But the hasty solution is empty and doesn't touch the soul. It leaves a vacuum, spiritual and aesthetic, that traditional country houses used to fill, and interrupts the rhythm of life, which traditional houses used to engender.

Country Kaleidoscope

The rhythms of the agricultural year set the pace of country life, and these rhythms still center around rice. This cycle of life, which was so fundamental to Japan until quite recently, is hardly felt in the cities. In tiny fields, clever machines now plant and harvest rice, though older people often hold out and do this work by hand. Similarly, rice is now usually dried mechanically, in hot air blowers, but often a farmer will sun-dry some of his harvest, mainly for his own family. Sun-drying is still common in the country for all kinds of foods.

Though some people in snow country have opted for plastic sheets to cover ground floor windows and walls in the winter, the traditional snow protectors of reed stalks are still much favored. Sometimes the traditional way is more satisfying and may even work better than clever plastic.

Tradition Reborn

Some twenty years ago, a young man from Tokyo saw the cover of a Japanese country life magazine and decided that this was the way he wanted to live. The cover featured three people on the porch of a simple, one-story thatched farmhouse. Nothing fancy, but somehow it called to the twenty-year-old Kenji Tsuchisawa, who has a way of making dreams materialize.

On the border of Tochigi and Ibaraki prefectures, tucked into the hills at the end of seven kilometers of winding dirt farm road, Tsuchisawa-san discovered a hopelessly derelict farmhouse by the side of a rice field that was being allowed to quietly biodegrade back into the environment. Amazingly, serendipitously, it turned out to be in the next town over from the house he had seen on the magazine cover. Though he suspected the house was beyond rescue, he bought it and started on the long road back to restoring it. The roof needed repair urgently, and luckily there were thatchers nearby who were able to restore the distinctive topping of golden reeds peculiar to that area. White plaster now covers the walls between dark brown wooden beams and supports, and strangely enough, the lovely Japanese style garden as you turn the corner into the front, gives the house almost the air of a pastoral English country cottage.

From the outside, the house has not been altered much except for the aluminum sashes and screens that are necessary concessions to winter winds and summer bugs. But the atmosphere is unchanged, and the wooden sliding doors and checkerboard window covers produce a playful surface of contrasting patterns. The coupling of the carpenters' skill with functional design makes for an interesting surface design.