Читать книгу Japan Country Living - Amy Sylvester Katoh - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHERITAGE

COUNTRY HOUSES

Japanese folk houses have their origins in the tropical climate of South-east Asia, and they have changed remarkably little despite the inhospitable climate of Japan. This architecture is effective during Japan's humid summers; it makes little provision for keeping warm in winter, or for privacy. The post and beam construction provides shelter against rains, earthquakes and typhoons. It can accommodate movable walls and thick roofs of thatch and can take the weight of heavy snow. A veranda (engawa) under the wide overhang of the roof provides a natural transition between the rooms within and nature without.

Houses were made of what the land offered, largely wood and straw, earth, bamboo, and paper. Roofs were always covered in the materials available in that area-thatch, shingles, grasses, bark, even stone in certain regions. Floors and walls were usually constructed of earth. In houses in northern Japan, it was not uncommon to find the family animals sheltered along with the rest of the household.

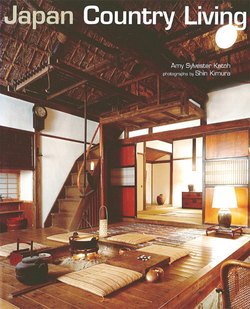

Walking into a Japanese farmhouse, the immediate reaction is visceral rather than cerebral. First impressions are of dark, of clutter, of jumble. Here is something of the earth, organic, alive, an extension of the land. The smells, the sights, the sounds are a meeting point between man and his environment. The Japanese farmhouse does not exclude nature, it is not a fortress. It is part of nature, and embraces it at every juncture.

The beauty of the traditional Japanese house was in the sensitive use of natural materials. Such a house was filled with ingenious ways in which man gave shape to his living environment. Poverty acted as a creative force to strengthen ingenuity and deftness. There was an overall harmony between man, his environment, and his way of living. Piety and respect for materials were evident throughout. Bamboo, wood, earth, paper, and straw were used in the most basic ways to keep the house standing and hold it together, both literally and figuratively. Proportions were easy and natural, based on a human scale. Ceilings were generally high, giving a feeling of space even in smaller rooms. And, too, the ceilings were textural and organic, often made of bound bamboo or of bare boards. Upper floors were used as work or storage areas, sometimes reserved for silkworm cultivation. Windows were few. Generally it was sliding doors and screens that opened to give light and air and access to the outside.

Though the floor plans of farmhouses have many regional variations, individual room arrangement was vague and unspecific. Each room was simple, basic, and nonpersonal; anyone could use a room for nearly any purpose. Private space was not provided or even a consideration.

At the heart of the farmhouse was the fire. Generally this was in an open hearth (irori), a stone-or-clay-lined pit sunk beneath the floor and filled with fine ash, in the middle of which charcoal was constantly kept burning. Over this a long decorative pot-hook Uizai-kagi) was suspended from a beam, and at the end hung a cast-iron pot or tea kettle.

Fire was an important presence in the house. Somewhere, in the irori or in a hibachi, it was kept burning at all times to keep a kettle boiling, things over the fire drying, food cooking. There was always the smell of the fire and of smoke. Smoke pervaded every crevice of the house. Smoke kept taut the straw ropes used to tie together beams, rafters, and thatch. People gathered around the hearth for warmth and to cook food, while overhead the smoke worked to dry foods, implements, and clothes. The irori was the gathering place for all members of the family. Old people rarely left it; their job was to tend the fire and the grandchildren while others worked.

The household altars-both Buddhist and Shinto-were, and still are, an omnipresent feature of the Japanese farmhouse. The gods and ancestors looked over-the-well-being of the household from their high place and protected the family. They were prayed to daily. The first food of the meal would be served to the gods before the family ate. The house, with its gods and fires, its natural materials, was a living presence, connecting man with his natural surroundings.

Kitchens were cold, dark, and usually only vaguely differentiated, sometimes little more than a corner of the dirt-floored indoor work area (doma). Running water and plumbing are both recent luxuries, as is gas for cooking. The bath and toilet were usually separate and outside, although recently, they have been included in the main house. Flush toilets even today are far from universal, and gradually, wood-fired baths have disappeared.

These once typical Japanese farmhouses have nearly vanished now. Simple and human proportions, natural materials masterfully utilized, inside-outside continuity, connectedness-the pillar of the genius of Japanese architecture is surely the honest farmhouse.

If one searches, scenes reminiscent of Japan's past still appear. People live simply, in tune with the rhythms of the land.

Only rarely, deep in the countryside, do you find clusters of thatched farmhouses. When I do, my heart leaps. I almost feel them before I see them, and when I look up, I see a friend. Even if no one is living in them, those straw and earth walls are alive. They are unspeakably beautiful and uncannily human, being of the same organic matter that we are. What will be the legacy of the plastic replacements that now plague the land? What will a child think of his or her heritage, never having seen the eloquent predecessors?

But, you never know. Once I was driving with friends through the mountains northwest of Kyoto in the late summer. The rice was a brilliant green. Layers of mountains surrounded us, mostly hidden in the mists. As we turned yet another curve in the road, suddenly a perfect, newly thatched house appeared, surrounded by rice fields and their guardian scarecrows with the misty mountains behind. Before the house a grandmother held a baby in her arms. We had to stop. When we asked why they decided to thatch their farmhouse, the grandmother smiled and replied that the young people, her son-in-Iaw and daughter, wanted it. It cost more, she said proudly, but it was worth it.

Inside-Outside

All the exterior and interior sliding doors and screens of a traditional Japanese house can be pushed aside or removed to open the entire structure to the outside and allow wind, sunlight, and even birds to penetrate to the heart of the house. The separation between inside and outside vanishes for the moment, and the entire house becomes a part of the natural surroundings, defined only by the roof and the raised, tatamimatted floor. This appealing feature is hardly possible with the traditional Western house, which is more like a fortress against the outside and a rebuttal of the elements. Whatever the cultural and historical reasons, this simplicity and flexibility of interior space and the careful blurring of distinctions between interior and exterior have fascinated and inspired the world's architects for the past century.

Snow dusts the roof of the Shindo house in winter.

The plan of the Woodruff house exterior.

The entranceway to the Shindo house is welcoming, even on a cold gray day.

Woodblocks of houses and shops decorate an old ticket.

A man and his dog in the snowy landscape of a hamlet of thatched houses in Miyama-cho, Kyoto Prefecture.

Gates were sometimes elaborate in country houses. Imposing doors, sometimes topped with a tiled gable, gave stature and importance to the household.