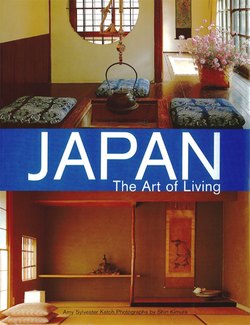

Читать книгу Japan the Art of Living - Amy Sylvester Katoh - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

Much of Japanese culture is unique. There is, for instance, the daily hot bath. Born in ancient times out of a need for ritual purity, it shocked the first European visitors, who saw it as a hedonistic addiction imperiling the health.

Just as distinctive is the traditional Japanese house. Prehistoric immigrants to Japan brought ancestral memories of the South Pacific and, nothing daunted by three seasons not at all tropical, built open, airy, up-off-the-ground dwellings beautifully suited to their new land's hot and humid summers but less appropriate for its chill winters. No matter, for, as I was tartly informed forty years ago while huddling over a tiny heater in a large room, in the winter one is supposed to be cold.

The traditional Japanese house is itself a work of art, although today few people can construct one or, if they could, would choose to live in it. Notions of creature comfort have changed, and it is not surprising that all through the countryside farm families have abandoned the traditional houses so appealing to our foreign eyes in favor of modern structures we may find uninspired or even ugly. To the families who lived in them it was no contest, and I admit that I would feel as they do. The new houses are functional and comfortable; the old were not, and by today's standards they never were, for all their much-praised shadows.

We are all familiar with the rhapsodies that sensitive critics have lavished on the traditional room and its magical ability to serve for living, dining, and sleeping, while all the time retaining its simple elegance. For some time I have suspected that such praise was based on the observation of rooms that were not lived in: those that the privileged could set aside solely for receiving guests, or those in a fine ryokan (inn). I think I have never seen a lived-in room that was not decidedly cluttered, for architecturally the traditional room affords no place for the miscellany one lives with. Commonly there is not even a place to put the tasteful flower arrangement or the thoughtfully chosen kakemono (hanging scroll), the tokonoma (alcove) being occupied by the television set. (And where else can it go? It would ruin the tatami.)

But my carping is beside the point. The traditional house represents an ideal, and so more than nostalgia sends us back to it for inspiration and renewal. Superbly crafted of fine woods, luminous paper, and sinewy reeds, technologically innovative in its modular design, this house challenges our standards and prods us to raise them.

More than anything else, the traditional house defines the Japanese style as we Westerners prefer to think of it. The Japanese, however, being a practical and resourceful people, do not so limit themselves. They know that there are times when the spirit breaks the bounds of quiet simplicity, and so they have created Nikko as well as lse, and love them both. They know that sometimes a theatrical splash is called for.

I cannot elucidate the ineffable something called "style." But I know that it does not constrict, it releases. By setting boundaries it offers freedom.

That is the spirit that enlivens Amy Katoh's piquant shop Blue & White, and it is the spirit that pervades the words and photographs of this book. It opens windows to fresh sensations and new delights.

— OLIVER STATLER