Читать книгу Japan the Art of Living - Amy Sylvester Katoh - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

The art of living-does such a thing exist in the crowded, noisy jangle of urban Japan? Is it alive even in rural Japan, where ugly power lines stretch over rice fields and rows of dried persimmons dangle not from the eaves of traditional thatch but from corrugated-iron rooftops? Oliver Statler, eminent author and longtime observer of Japan, wonders if such a thing as a beautiful room exists in today's Japan. Unfortunately his doubt is legitimate in some respects. Although the Japanese aesthetic influences designers everywhere and the ideal of the elegantly simple, all-purpose Japanese room inspires many, the sad fact is that the lack of space and what Mr. Statler has called the "litter of living"-throw rugs, television sets, and vacuum cleaners-do not allow all rooms to be beautiful.

Visitors come to Japan with certain expectations. They expect to find the Japan of myth and movie, where people dressed in kimono live in perfectly appointed tatami rooms in quaint and lovely towns. They assume they will find thatched-roof houses, ancient temples, and exquisite modern architecture surrounded by nature perfected, hillsides dotted with green patchwork rice paddies. The truth is that this Japan does not exist, neither in the cacophony of sights and sounds and garish neon of Tokyo streets, nor in the countryside that struggles constantly to emulate Tokyo's glitz.

Japan perfect is a myth. One must, instead, develop a special eye and look for beauty where it is unexpected, where it is not obvious. Call it a "Japan eye," an art of seeing that allows one to sift through the helter-skelter architecture, through the chaos of telephone poles and electric wires, through the frenzy of bicycles, children, and umbrellas to see the beauty and elements of order within. Looking at one's surroundings with a Japan eye means looking past the garish, blue plastic tubs and seeing only the lovely waterlilies that are blooming within. The Japan eye discerns a world of beauty at the concrete police box with its one fresh flower in a glass jam jar, and at the tiny vegetable shop with its neat tiers of oranges, turnips, and spinach.

This eye for beauty, order, and display observes the inside of the house as well, looking beyond the clutter to the small, budding camellia in the genkan (entrance hall); the still life of fruit in the tokonoma; the translucent washi (handmade paper) stretched over a checkerboard shoji (paper-covered, wooden sliding door); the artfully set table awaiting the arrival of a tray of thoughtfully arranged dishes of food, beautiful juxtapositions of shape, color, and texture. The Japan eye is selective and discriminating. It sees the small touches of beauty amid much that is commercial and mass-produced.

This eye delights too in the number of beautiful public spaces evolving from the mingling of influences from East and West in Tokyo and other urban centers. A new design-and a new lifestyle-of beauty and art is blossoming in restaurants, boutiques, galleries, design studios, and "concept buildings" like AXIS in Roppongi and the Spiral building in Aoyama. These public, distinctly Japanese solutions to the challenge of fusing the best of the traditions of the East and the modern technology of the West hold promise of a future when people throughout the world will seek to incorporate the serenity of traditional style into a modern, twenty-first-century world thirsty for warmth and beauty.

Living with a sense of Japanese style and design in a modern household involves breaking rules: living with panache. Let's call it Japanache, a new kind of international style. What is Japanache? It is the flair for living anywhere today and distilling the essence of Japanese design and spirit from the past. Making the traditional come alive in a modern context requires panache. It entails the unlocking of the mind and the eye. No longer is there just one way of doing or seeing things. The aim is to try all the possible ways of using things, doing things, creating new combinations.

I vividly remember years ago inviting my Anglophile but traditional Japanese father-in -law for afternoon tea. I was a young bride, and had starched the best linen and polished the silverware in anticipation of his visit. I had baked special cakes and cookies in his honor, but horrified him by presenting them on a latticed bamboo tray. "Oh, no, Amy," he exclaimed in horror at my ignorance. "That tray is not for cookies!" As continental and cosmopolitan as he was, for him the tray I had used was made for one purpose only, the serving of saba (buckwheat noodles), and could not be used otherwise! That day I was taught an important lesson about the relationship of form and function in Japan: there are rules about using certain things for certain functions, and I should try to know and respect them. But as a foreigner, I was not restricted by the boundaries of "one form, one purpose" thinking. I was free to use a bamboo noodle tray as I saw fit, just as today I enjoy filling a straw backpack that may once have carried firewood or vegetables with masses of flowers, or lining up old blue and white porcelain sake-cup rests and putting new white candles in them.

By all means, experiment. Surprise yourself (and my father-in-law!). Take these antiques and traditional crafts, textiles, kites, and flowers--the bits and pieces of beautiful Japan that you have discovered- and put them to new and different uses. They will come alive with their new role in life.

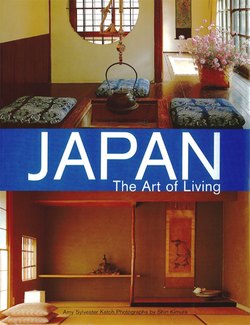

In more than three hundred beautiful photographs, we take you into the homes of Japanese and Westerners who have brought Japanese art, antiques, and, most of all, the spirit of Japanese aesthetics to their best-loved spaces- their tables, rooms, entrance ways, walls. We offer these lovely examples of the Japanese art of living as a new source of ideas for inspiration and emulation.

Instill your house with a Japanese sensibility. All it takes is some imagination and a few touches here and there. Experiment, explore, and exaggerate with Japanache!

JAPANESE MARKETS

The markets of Japan are rich in people and products. Among those worth visiting are Tsukiji in Tokyo for fish; the morning market in Wajima for seafood and local produce; Nishiki Koji in Kyoto for food of all sorts; Toji and Kitano in Kyoto for everything from antiques to octopus; and the farmers' market in Takayama.

Deep appreciation to the generous people who opened their doors to our camera to give definition to JAPAN The Art of Living

Mr. and Mrs. James Adachi, Mr. and Mrs. John Alkire, Mr. and Mrs. Hassan Askari, Mr. and Mrs. Rex Bennett, Mr. A.B. Clarke, Mr. and Mrs. Carlo Colombo, Madame Nicole Depeyre, Mr. and Mrs. Matthew Forrest, Mr. and Mrs. Jean-Claude Froidevaux, Mr. lchiro Hattori, Mr. and Mrs. Henk Hocksbergen, Dr. and Mrs. Peter Huggler, Mr. and Mrs. Hiroyasu lsoda, Mr. and Mrs. Yasuhiko Kida, Mr. and Mrs. Donald Knode, Mr. John McGee, Ms. Kathryn Milan, Mr. and Mrs. Takamitsu Mitsui, Dr. and Mrs. Komei Okamoto, Dr. Joseph A.Precker and Mr. Robert Wilk, Mr. and Mrs. James Russell, Mr. and Mrs. Eric Sackheim, Ms. Patricia Salmon, Mr. and Mrs. Stephen Stonefield, Mr. and Mrs. John Sullivan, Mr. and Mrs. Yoshihiro Takishita, Ms. Patricia Waizer

With head bowed low in thanks to

Nasreen Askari, Sumiko Enbutsu, Judith Forrest, Keiko Kimura, Miwako Kimura, Seong Ja Lee, Kyoko Machida, Katharine Markulin, Nucy Meech, Mitsuko Minowa, Tadashi Morita, Julia Meech Pekarik, Nancy Ukai Russell, Lea Sneider, Junko Suzuki, Yukiko Takahashi, Mitsuo Toyoda, Fumi Ukai, and countless other teachers, counselors, and encouragers whose belief in this project helped make it happen

Very special thanks to

Harumi Nibe and Patricia Salmon

NOTE: The landscape architecture for John McGee's seventeenth-century Kyoto house, shown on page 6, was done by Marc Peter Keane.