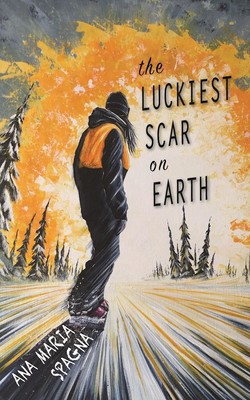

Читать книгу The Luckiest Scar on Earth - Ana Maria Spagna - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

My snowboards were the first things packed in the U-Haul trailer. Before our clothes or our photo albums. Before the canning jars or the ancient desktop computer or the futons or Mom’s tennis rackets. You should try fitting bed frames around boot bindings. No easy task. Mom crawled in to re-strap the boards upright in the corner.

“Why bother?” I said. “I won’t need them anymore.”

I meant it. I’d sold all my flashy gear, traded in all the polar fleece and Gore-Tex for wool and Carhartts. I grew my hair long. I even left my best boots at Goodwill hoping they’d go to some kid who wanted to ride fast the way I used to. Someone who cared. Me, I didn’t care. I didn’t plan to race ever again. I figured a brand new start is a brand new start. But Mom? She wouldn’t let me leave the boards behind. Even when I tossed them on the pile to take to Goodwill with the boots, she’d yanked them back out. I didn’t get it. Mom was no huge fan of snowboarding.

Now she wanted me to keep these boards, three of them, even though they took up way too much space in the trailer. Maybe it had to do with money. The three boards combined, she pointed out, cost more than the used Kia that would have to drag our whole lives’ possessions a thousand miles west.

“Just give me a hand here, Charlotte,” she said.

We strapped the snowboards one beside the other with towels tucked between them so as not to scratch the base, and wedged the rest of everything around them. Smog obscured the Rockies in the distance, and sweat streamed down my neck as we lugged crates of kitchen gadgets and keepsakes I hadn’t known she’d kept. A box of trophies. A folder of newspaper clippings. By noon the job was complete. Mom checked the trailer hitch, poured me a cup of cocoa from the thermos, and climbed into the driver’s seat. I took the passenger seat—same as my whole life—and we pulled away from the curb.

I only looked back once. The house sat empty, the only house I ever remembered living in. The lawn was mowed, sure, the realtor made certain of that, but the bright curtains Mom sewed were gone from the windows, the bicycles gone from the porch. The place looked cold and empty and lonely. Precisely the way I felt. We drove past my grade school, then my middle school, then the high school where I should’ve been starting in a week.

On the edge of town, we passed New Life Ministries where Mom had worked for the pastor, Steve Carlisle, as long as I could remember. When I was a kid I thought God lived in that place. I could feel it—this presence, this magic, this something—when we raised our arms high in praise, but now that feeling seemed bigger than a building could hold, and the place I felt it most wasn’t at church but high in the mountains. Like I could explain that to my mom. I could barely explain it to myself. Something about Steve Carlisle wasn’t right. Her desk sat beside his, but his looked pristine, untouched. Hers, you could tell, was where all the action took place. New Life had once been a small place, now the buildings covered an entire city block. A helicopter pad sat on top of one of them. A helicopter pad! How could a guy be doing well enough to have a helicopter and still fire his first and best employee?

“Not fired, Honey,” Mom told me when I asked for the millionth time. “Laid off.”

I didn’t believe her, and she knew it.

Finally, we approached the mountains, my mountains, coated white on top with the first skiff of early snow, the kind that always made me shiver with excitement. Huge rounded ridges, steep-angled slabs, snaggle-toothed summits folding one into the next like origami. Anyone who saw that view would know that’s heaven. Right there. And anyone who decided to leave would be crazy. We drove west toward them—so many of them 14,000 feet tall or taller—and followed the freeway into them, the Kia groaning with the effort of pulling the U-Haul, and when we started down the other side, leaving felt wrong, like slipping, like losing my balance, like taking a tumble helmet-first down a steep slope, not the chest swoop thrill but the somersaulting terror that when you stop, you won’t be able to stand.

Then, suddenly, it got worse.

“I’ve been in touch with your father,” my mom said.

“What?”

I couldn’t believe she waited until we were on the freeway to spring this on me.

“We’ll be seeing him soon,” she said.

I took a big gulp of cocoa. I used to dream of her saying something like this. I’d fantasize about how he’d show up at the door with flowers and a briefcase, how I’d set the table for three, how we’d sit together in a pew at church, how he’d read to me at night, making up funny voices for different characters. But that was a long time ago. I’d gotten used to our life without him. I liked our life without him. Now, this.

I leaned my head against the window to watch the Rockies grow smaller and smaller in the side mirror. Ahead of us, rolling hills stretched out dirty brown, nothing green for miles. I knew Washington had mountains, too, but they hardly counted. I’d read that the tallest peaks in the Cascades, besides the volcanoes, weren’t even 9,000 feet tall, hardly high enough for a ski area if weather kept on like it had been, climate change and all. Of course, it could be worse. We could be moving to Nebraska. Or Mississippi. Then again, if we moved to those places I wouldn’t have this meet-your-long-lost-dad pressure to deal with.

“Charlotte, did you hear me? You need to spend time with him.”

“Why?”

“Because he’s your father,” she said.

“I won’t call him Dad or anything.”

“Fine. Call him Larry,” she said.

“What will I do with him?”

“Why not snowboard?”

Snowboard? Was this the whole reason she wouldn’t let me leave my boards at Goodwill?

“Does he even know how?”

She shrugged. “You can find out.”

I seriously did not appreciate my mom thinking up schemes like this.

“Whatever,” I said.

What did I even remember about Larry Potts? Not much. I was five when my mom took me to Denver. Larry never came to visit. Never called. Not once. What did I remember? Mostly: hair. I remembered a bushy beard scratchy against my cheek, and I remembered holding strands of his ponytail in one fist, which meant he must’ve bent way down to pay attention to me—I was only five—or picked me up to hold me. But I didn’t remember that. I didn’t remember his arms or his chest or his face. I remembered his smell. Sometimes when I passed a pine tree in our old neighborhood, I’d break a needle in my hand to smell that smell, and I’d have this feeling like when you hear an old song you don’t even think you know, and suddenly you’re singing all the words.

What didn’t I remember? The scar. Not at all. Which is seriously strange. I knew about it, of course. Mom told me all about the accident, how once back in his logging days a chainsaw kicked back on him, leaving a four-inch scar running from the bridge of his nose to his hairline, white as glue, a half-inch wide. I pictured it like Frankenstein, only uglier. But I didn’t remember it at all.

All I remembered was the hole where he should’ve been. Two plates at the dinner table instead of three. Two seats in the pew at church.

On the car radio Steve Carlisle’s voice came from nowhere, soothing, almost purring. I’d heard this sermon before—they played it all the time on the Christian station Mom listened to—and I could picture him pacing the New Life stage in blue jeans, the spotlight on him only. I could see him sitting on the stage edge, legs dangling, leaning forward, as if to get closer to us. I could imagine his deep blue eyes, how he could meet your gaze and hold it long.

Mom shut it off quick.

We cruised through Wyoming and into Idaho, states I’d visited before on rowdy buses, heading to snowboard competitions with the team. I’d been to California and Oregon, even Vermont. But somehow never Washington. When the team was going there, something always came up. I’d never really thought about it before now.

I checked for texts but knew there’d be none. Everyone was getting ready for high school. Everyone had other plans. I hardly kept in touch with my friends between ski seasons anyway. I lived only for winter. Used to.

I dug for a snack.

Bags of bulk dried fruit. Dry packets of drink mix. I opened the hummus and spread it on crackers to hand to her one at a time while she drove and took a few slices of cheese, medium cheddar, for myself. My stomach growled. I’d die for a turkey burger. I’d even settle for a veggie burger. But I didn’t want to be a whiner. One thing all those years of snowboard competitions taught me: no matter what, you don’t complain. You might be cold, icy, sore, frustrated, bored, but you never, ever, complain. Honestly, it was half the key to winning.

At least we had cocoa. Two thermoses full. She let me start drinking cocoa when I threw a fit as a kid. Even a six-year-old knows it’s lame to drink herbal tea. Mom worried about me drinking too much sugar. Once she said it’s a bad sign, an early indication of alcoholism, like Larry’s. But come on. Do six-year-olds have early indications of anything? I just like chocolate, perfectly normal, I told her, and I’d been drinking cocoa ever since.

We stopped at a motel in a small town in southern Idaho far from the highway, an off-brand place with covered parking and a separate space for the U-Haul. We unloaded our backpacks, changed into our suits and found the swimming pool full of loud splashing kids. We jumped in right away, but it was too crowded to stay in, so we sat together on lounge chairs watching them play. The underwater pool lights made their legs look noodly, and we laughed about that, and everything was fine until right when the sun set, and the moon started to rise, the brightest moon I’d ever seen, and I ached to be home so bad I thought I’d throw up.

The next morning as we drove down the deserted main street, headed for the highway, Mom slipped in Born to Run, and we sang along with The Boss like we always had.

“We’ll run ’til we drop. Baby we’ll never go back.”

Only this time, I didn’t mean it. Not one bit. In my heart I knew I wanted to go back. I swore to myself I’d go back to Colorado first chance I got.

Finally, after two long days, we crossed a wide river and weaved through a patchwork of farms, nothing like what I pictured Washington to be. No moss. No ferns. We passed orchards with trees heavy with apples turning red, and smelled the faint smell of forest fire smoke, and kept heading farther and farther up this steep twisty highway through tall trees, much taller than the trees in Colorado, until we passed a small sign that read: Timberbowl Ski Area. You could see the ancient two-seat chairlift above the trees and single lodge building at the base made of actual logs, like an old-timey movie set. Clouds had moved in, and the cottonwoods, at high elevation, had already turned bright yellow. Their leaves fluttered in the last wisps of the sun. I cracked the car window—it was plenty cold—and the smell struck me hard. Unmistakable. Almost painful. I couldn’t see the mountains through the trees, but I could feel them all around, calling me, taunting me. I slumped low in my seat and pretended to sleep.

The new snow smell would not leave me alone.