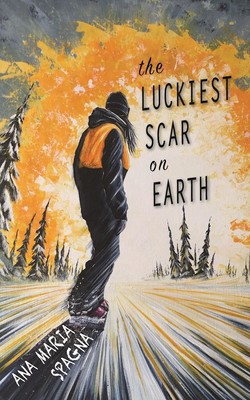

Читать книгу The Luckiest Scar on Earth - Ana Maria Spagna - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

The way he looked came as a shock. The scar to start with, yes—a long ridge of white puckered skin as wide and ragged as a mountain range on a map with hatch marks where the stitches used to be—but also his mud-brown eyes and his cheekbones set a notch higher than normal, and the way he half-smiled with one side of his mouth tilted up like a sinking ship. Except for his long ponytail and beard, he looked a lot like me. Or vice versa. Like seeing myself reflected perfectly in some time-lapse mirror.

He helped us haul a used couch upstairs to our new apartment the day after we arrived, a tiny place with cinder block walls, on a wide busy street lined with billboards, across the street from a mattress store. Afterwards Mom hung around for a while, making small talk about the weather and where to find more cheap furniture—the room was empty besides the couch and the three snowboards—and then she just up and left. She drove off with some lame excuse, and we were on our own, this towering Sasquatch, all hair and scar, and me, sitting side by side on the saggy cushions.

“How was the trip?” he asked.

“Fine,” I said. “Long.”

Silence.

Larry was no more a talker than me.

“Those yours?” he asked. He gestured to where the three snowboards stood in the corner, still with towels duct-taped around them like bandages.

“Yeah, used to be.”

“Used to be?”

“Long story.”

I took a deep breath.

“Do you ever go up to Timberbowl?” I asked.

“Sure,” he said. He was lying. Or exaggerating.

He started to explain how he used to telemark ski in the backcountry but it’d been a long time since he wasn’t in the shape he used to be when he worked as a logger and lift tickets were expensive, you know, and he didn’t get much work truck driving in winter. It seemed like he was making excuses. Considering how he’d treated me—or not treated me—so far in my life, I didn’t feel like cutting him much slack.

“So you’re not much of a skier,” I said.

He turned toward me, and I saw the scar cleaving his forehead turn rosy. I’d learn in no time this was a bad sign, an indication you might say, the color of his scar. Usually it was white, yes, but when Larry got angry, it turned pink, then red, then dark purple.

He caught me staring.

“The luckiest scar on earth,” he said, drawing his index finger down the length from his hairline to where it stopped between his eyes.

“Lucky?”

“Lucky because I easily could’ve died right then and there. Could’ve severed my carotid or split my skull.” He paused. “And lucky because if I hadn’t had the accident I would never have met your mom.” He looked right at me. “Or had you.”

I wasn’t about to talk about that. I wasn’t even going to think about it. I had to change the subject and quick. I only had one idea after all, thanks to my mom, one fallback plan to avoid stupid conversations about the past, on a saggy couch in a dank apartment, so I went with it.

“If you get a part-time job up at Timberbowl, we’d both get free season passes,” I said. “Then you could learn.”

“Learn what? I told you, I already know how to ski.”

“To ride. To snowboard. You gotta learn to snowboard, Larry.”

More dare than suggestion.

He stared for a second, then the right side of his mouth tilted up. Maybe because I called him Larry.

“I’d get a job myself,” I said. “But I’m not old enough. You have to be sixteen, or maybe fifteen and a half. It has to be you.”

“I’ll think about it,” he said.

Nothing about that fall seemed easy. Midland High was less than half the size of my middle school, which meant everyone already knew each other, and close enough that I could walk home at lunch, which I did for the first three weeks until I got tired of hustling back for the fourth period bell, and gave up to sit alone at a picnic table most days with my nose in a book. With Mom unemployed, we qualified for free lunch, plus it was a way to get pizza and fries into my diet. Within a couple weeks, I noticed my Carhartts getting too tight around the waist. But it hardly mattered since the pants were getting too short, too. I’d read once that most girls stop growing around fourteen, but I hadn’t yet. I wondered if I ever would.

Mom spent her time job-searching. Sometimes in the afternoon she hit balls at the tennis courts at the community college across town. Once or twice I went with her, but usually I didn’t. I didn’t feel up to it. Tennis had never been my thing. Snowboarding had been my thing. Racing had been my thing.

I remembered how it felt to stand at the top of a race course ready to drop, then to fly down, taking one turn then the next, blood pumping like river water charging, how you think without thinking and shift your weight from heels to toes, knees bent, arms low, while snowflakes pelt against your face. Trees flashing past, gates fluttering, snow shushing, then scraping, then shushing again. And I remembered the rush that came when you had only a half-second to shave, and you could see the girl across from you straining, and you started to pull ahead, and you grew stronger, faster, surer. Here’s the truth: I raced to win. Period.

At home in the dingy apartment, I discovered a station on the far left of the FM dial on the old clock radio Mom kept on the kitchen counter to make sure I wouldn’t be late to school. As if I’d ever been late to school in my life. KTMR from the college broadcast in town and streamed online, too. They played bands I’d learned to like in Colorado by hanging around the older racers, the ski patrol, the regulars my mom still insisted on calling “ski bums” as if any kind of bum could afford the gear it takes. Each morning on KTMR the college DJs reported the freezing level in the Cascades and eventually the amount of accumulated snow at “the Bowl” as they called it. I figured that’s how I’d find out ski season had begun.

But Larry beat them to it.

On the Saturday before Thanksgiving he showed up before dawn in work jeans and a worn-out canvas coat toting a pair of used snowboard boots in my size, women’s nine. How did he even know?

“Opening day,” he said. “Don’t dally.”

Turned out he had applied for a job after all, as a lift operator, a liftie, the guy who stands by the chairlift all day, helping kids get situated, switching the power off when someone slips so they don’t get clobbered by the next chair swinging past. Not the most exciting way to spend eight hours—a job meant for a teenager, really—but enough to get us both free passes. Still standing in the doorway, he handed me my temporary pass—I’d have to get my photo taken to get the real one—and then he showed me his, a hard plastic permanent card, with a photo and all.

“Employee,” it read. “Snowboarder.”

“Snowboarder?”

“You said you’d show me how.”

“Did I?”

“You did.”

My mom sipped tea in her sweats while I tried on the boots. It still felt strange, the three of us all in one room, and the boots felt strange, too, sloppy and worn, too tight around the arches, too loose in the heel, but fine, really, considering they were a gift. Perfectly functional. Mom unwrapped my boards, which had stayed in the corner of the living room since fall. She kissed my cheek and ran her hands through my hair as if she were sending me off to kindergarten, then waved goodbye from the balcony as we loaded into Larry’s old beater Ford pickup. And we were off.

He steered out of town through the orchards and up the twisty highway into a thick pine forest. The local radio call-in show, KZZR, buzzed from one functioning speaker listing grain prices, announcing the upcoming rummage sale at the Lutheran church, advertising diners. We drove higher to where slush piled on the roadside, then higher yet into fresh new snow. I rolled down the window to let the flakes settle in the loose wisps of hair around my ears, and Larry didn’t say a word, just grinned.

We were the first ones in the lot. I hadn’t seen Timberbowl since that first day when I drove past with my mom, and the place didn’t look any more impressive. The chairs were slow, the lodge small, and the top of the so-called mountain was flat and long, more ridge than peak. And what about that name? Timberbowl? Trees so tight you’d never ride through them, narrow runs lined by steep cliffs some crazy boarder would jump off. Not me. Other snowboarders did tricks. Other snowboarders had attitude. I just went fast.

Larry had bought a used snowboard and a humungous pair of used boots that must’ve been men’s size fourteen. He stuffed his feet into them sitting sideways in the cab of the truck, then strode toward the lift line without waiting to see if I was ready. I had to half-jog to keep up. He refused to start on a beginner run and instead rode with me to the very top, where he fell hard trying to dismount, and then fell again trying to buckle his boots, and then fell pretty much the rest of the day. His old canvas coat soaked up wet snow like a sponge, but he never complained. He’d fall then stand and lean way back into the hill, arms stretched wide, looking like a telephone pole or a tottery giant.

“Mira,” he said. Then he fell again.

On long drives, Larry studied Spanish because, he said, regular books-on-tape put him to sleep. Learning Spanish was one of his New Year’s resolutions. After a half day on the slopes, before he’d made even a single turn, he told me he had a second one: linking fifty turns on his snowboard.

Larry believed in New Year’s resolutions, he said, and kept them without fail.

“What’s yours?” he asked.

“I don’t believe in New Year’s resolutions,” I said.

After a while, he sent me off alone to try out the more difficult runs.

“Have some real fun,” he said. “Knock yourself out.”

I could tell he could use a rest, and I thought I wouldn’t mind checking out the rest of the mountain, but as soon as I sat alone on the chair, I started wondering where my friends in Colorado were riding. I got off at the top and gazed around at the sea of peaks, not one of them I could name, and the feeling got worse. Snowboarding in this place felt wrong, disloyal, like abandoning someone you love or being abandoned. Hollow. Lost. Exactly the reason I’d decided to give it up.

I dropped off the summit fast, away from the view, and made my way down one steep mogul pitch and began to feel alright again. That fell apart when I passed the snow park where the only other snowboarders on the hill, all guys, stood watching me pass. One guy in particular stood splay-legged and arms-crossed and stared long. I tried not to be bothered. I’d gotten used to it in Colorado, how a fast girl on a snowboard still surprised a lot of people, but it was still hard.

After a few runs I gave up—it was better, by far, to hang out with Larry—and after a couple of weekends, we had a routine. He brought us sack lunches—sandwiches, fruit, carrot slices. He was more like my mother than I’d have imagined: no soggy burgers, no nacho cheese chips, definitely no two-dollar Cokes. He kept our water bottles in a backpack clipped with a carabiner to the lift line in a long row of backpacks or, later, as we got to know the place better, clipped to a limb in the woods beside one of the slower runs. We stopped to eat and drink, and then kept right on boarding. Unless we needed the bathroom. Then we headed to the lodge.

The lodge at Timberbowl had a large empty room with a faint musty smell, high ceilings and long rows of tables with benches. No high-end restaurant or bar. The rental shop looked like the back of someone’s garage. The oldest section, the log structure, had an actual fireplace and some of the ski instructors tossed half-rounds into it when it started to burn low. Kids hung their gloves and coats next to it. But we didn’t stay inside long. Larry preferred to sit at the tables outside.

“Why are we wearing all these clothes anyway? To get sweaty smelling French fries and sweaty kids?”

He had a point.

By afternoon, often enough, what started as snow turned to rain, then froze, so even the easiest terrain became challenging, and when you fell, as Larry so often did, it hurt. I worried for him a little, but that was one advantage of that oversized canvas coat, he had a little padding. We stayed until the very last minute the chairlift was open—only 4:00 p.m. and already getting dark—until we were nearly the last people left on the mountain, and on the ride home he showed off the bruises on his forearms and elbows.

“You should see my backside.”

“Who says backside, Larry? No one says backside. Do you mean your butt?”

“Not exactly. Just the stuff I can’t see in the mirror, the unseen side. You know that’s what they call this side of the mountains? The Backside.”

“Great. Mom moves me from the Front Range to the Backside.”

“Why did she move you?” he asked.

I sat up straight and pulled my shoulders back. He didn’t know?

“I mean I’m glad she did, Charlotte. But I don’t get it.”

“She lost her job. She got laid off.”

“That doesn’t sound right. Your mother would be the last employee left in the last company in the whole corporate world.”

“She worked for a church, Larry. Not a corporation.”

He made a low noise, a growl like a dog or like a grandpa, which I suppose he was old enough to be. “Same difference,” he said.

I tried to set one of the pickup’s preset radio stations to KTMR, but Larry kept changing it back, so we made a truce. In the morning, he could listen to the chatter on KZZR. On the way home, we’d get to hear the DJs at KTMR talk about the newest bands so quietly you had to turn up the volume. Not that Larry cared. We hardly ever talked on the way home from the mountain, too tired for small talk. But sometimes, between songs, KTMR got too quiet even for me.

One afternoon, I switched the station, and right away we heard the DJ mention Timberbowl. Larry reached for the volume as the DJ explained the news: an Australian corporation called Evergreen had bought Timberbowl and planned to build a small airfield, three golf courses, and about eight hundred condos.

“Eight hundred? Eight hundred?” Larry cried. His scar throbbed mauve.

Just then, we passed the spur road that leads up the east side of Goat Peak, the highest mountain visible from town, home to Timberbowl and some old logging scars and maybe soon a few hundred condominiums. A front-end loader sat idling.

The scar edged toward magenta.

“Jesus,” he said. “They’re starting already.”

I tried to ignore the name-in-vain thing.

“What’s the big deal, Larry? You have to admit Timberbowl could use some spiffing up.” I thought of the outdated chairlifts, the crumbly old lodge.

Larry just shook his head and drove the rest of the way into town in silence.

He dropped me off, and I walked the cement stairs to the cement walkway outside the apartment door. Like a motel room in a bad old movie. A heavy gray door like a dozen other heavy gray doors. No lawn, no herb garden, no view of the mountains. The covered walkway kept sunlight from coming in the front windows. Gloomy. Glum. Larry didn’t seem to notice. He waved to my mom from the driver’s seat like a nervous boyfriend, like he was trying to prove something.

So it went through early winter. All week: school, home, school, home. On Saturday, Larry showed up before light, honked once in the parking lot where he’d already turned around so his headlights faced the mountains. I’d run down, hop in, and we’d be off. I really thought that’s how it would stay. Just the two of us snowboarding, getting to know one another.

But, of course, things changed.

One day just before Christmas break, Larry and I passed the Timberbowl ski team at practice. The kids huddled in groups wearing their matching lime-green Timberbowl coats, bouncing in their bindings, waiting their turns, yelling for their teammates. I knew exactly how they felt. Standing like that, eager to race, had been as much a part of my life as brushing my teeth or doing homework or going to church on Sunday. The coach stood midway down the course. She was smaller than some of the bigger kids, but louder too, as she hollered encouragement and clapped her mittened hands together hard, even though they’d make no noise that anyone could hear.

Larry skidded to a stop to watch two kids go head-to-head down the slalom course on skis. He whistled through his teeth.

“They’re pretty good,” he said.

I felt a twinge of jealousy and shifted my weight to continue down the fall line. I couldn’t believe eight-year-old boys could impress him.

“But they’re not as good as you,” he said to my back as I glided past. As if he’d read my mind.

I stopped and pretended to clean my goggles. I wanted to tell him I used to be a lot better than pretty good. I used to be really good. I wanted to say racing in the Cascades is not the same as racing in the Rockies. Not even close. I wanted to say: that’s the past and this is now. But when I turned to look at him, he was grinning that lopsided grin.

“Why don’t you get back into it?”

More dare than suggestion.

“I’ll think about it,” I said.