Читать книгу Plasticus Maritimus - Ana Pego - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

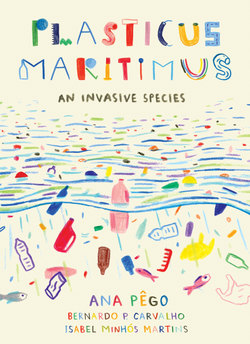

ОглавлениеA species that doesn’t exist . . . but here it is

This field guide aims to help us understand a species that doesn’t belong to the natural world but that has become common on our beaches and in our oceans—ocean plastic. When I came across it more and more, I thought it was important to give it a scientific name. After all, things become more real to us when we name them and give them an identity.

Inspired by the terminology that scientists use, I invented a name for this species: Plasticus maritimus. Plasticus because it is a species made of plastic and maritimus because it can be found in all seas and coastal areas worldwide. I classified it as an invasive species—that is, a species that is not native to the place where it’s found and causes harm in the new environment.

Plasticus maritimus is invasive wherever it appears.

WHY SUCH COMPLICATED SCIENTIFIC NAMES?

As you may have noticed, scientific names are always designated in Latin and are composed of two words written in italics. It’s not just to make things more complicated and important-sounding. It’s to ensure that every species has its own name and that we don’t confuse two different species of plants or animals.

We all know the common names of some plants and animals. But these common names are different in different countries and even in different regions of the same country. So, for example, the scientific name helps clear up any doubt when you call a particular wild flower a devil’s paintbrush and your friend insists it’s an orange hawkweed. When you look in your wildflower field guide, you find you’re both right. This wildflower has many common names. But the scientific name for the plant is Hieracium aurantiacum. The field guide also tells you that the wildflower that you found in British Columbia is originally from southern and central Europe.

The scientific name allows us to observe in detail the aspects that scientists study when they are examining a particular species. Scientists want to determine the family to which a species belongs; its characteristics, including its life cycle; and where it’s found on the planet—whether in a particular region or in many regions.

For example, Tursiops truncatus (common bottlenose dolphin) is the name of a species of dolphin that has a resident population in the Sado estuary in Portugal. But in the Azores, Portugal, a species called Delphinus delphis (short-beaked common dolphin) is more widespread. They’re both dolphins, but they’re two distinct species.

The name of a species is made up of

1.a generic or genus name (always begins with a capital letter), and

2.a specific or species name (always written in lowercase letters).

Plasticus maritimus

Together, these two terms identify the species and avoid big misunderstandings.

Some species, including this one, also have subspecies. In this case, the subspecies name differentiates between common versions of the species (Plasticus maritimus vulgaris) and those that are more rare (Plasticus maritimus exoticus).

What species is this?

IDENTIFICATION SHEET

Scientific name:

Family: Plasticidae.

This is the family of species that possess some type of plastic in their constitution.

Characteristics: This species appears in a wide variety of forms. Usually, these forms are identifiable—we can easily recognize a fishing net or a water bottle. However, Plasticus maritimus often turns up in unfamiliar ways. In these cases, we can’t tell what the object is and we must investigate.

Color: Plasticus maritimus can be any color, including an undetectable color. That is, it may be transparent or appear in such small particles that it’s impossible to see what color it is.

Dimensions: This species can be found in all sizes from very large to very small and is sometimes even invisible to the naked eye.

Means of movement: In general, Plasticus maritimus moves easily and rapidly depending on the winds and currents. The lightest examples fly and float but heavier ones may remain a long time at the bottom of the sea.

Distribution: This species is found in all of the world’s oceans and coastal areas.

Imitative abilities: Plasticus maritimus is a champion at mimicry. It can change itself to look like animals. For example, it can imitate jellyfish that are food for turtles. It can also make itself so small that it mixes in with and is mistaken for plankton.

Adaptability: This species adapts easily to all ecosystems and demonstrates great tolerance for differences in temperature and salinity. This is why, over the last fifty years, its population has increased exponentially and in an uncontrolled manner, affecting all marine and coastal habitats in the world. Plasticus maritimus integrates so well into our lives that we don’t even notice it. As a result, it is an extremely dangerous species.

Life cycle: The first phase of the life of Plasticus maritimus is on land, so it is confused with the species Plasticus terrestris (meaning land-dwelling). The age at which it passes into the aquatic environment is variable. It may happen after a few minutes, a few days, or many years of terrestrial life. Its arrival in the ocean may happen directly or indirectly, in which case it passes first through streams, rivers, or other waterways.

Toxicity: Toxicity is generally high, but it is variable. The most toxic forms are those with additives that make this species softer, or more flexible, or more long-lasting. There are also pollutants in the oceans that adhere to the surface of plastics during their stay at sea.

Endemic/exotic/invasive: Not endemic (not naturally occurring in a certain area); an exotic and invasive species.

Conservation status: Currently, there are no threats to Plasticus maritimus. It is a threat itself!

Eradication: The greatest threats to the existence of Plasticus maritimus would be to eradicate disposable plastic products (at present 50 percent of plastic is used only once), reduce the production and consumption of plastic products, and increase reuse and recycling of plastic products.

Plasticus maritimus is on the list of exotic invasive species that threaten the biodiversity of the oceans and our existence. Its eradication is urgent! If you come across any, pick it up and put it in a plastics recycling bin, if possible, or a garbage container.

How much plastic is in the sea?

An American scientist named Jenna Jambeck was the lead author of a big research study to find out how much plastic goes into the oceans every year. Making these calculations is not easy, so it took a large team of scientists from many different fields. The study concluded that every year, about 9 million tons (8 million metric tons) of plastic ends up in the oceans. Almost all of it is packaging!

This is equivalent to about 1,000 tons (900 metric tons) of plastic being dumped into the sea every hour. Every single minute, that’s a truckload full of plastic, without stopping.

The most recent estimates also indicate that with population growth and the increase in plastic consumption, this number will double by 2025. This is how we come to the sad conclusion that by 2050, there will be more plastic in the sea than fish.

Nine million tons (8 million metric tons) of plastic ends up in the oceans every year.

Where does the plastic go?

We might think that the plastic ends up in the most populated parts of the world or near the coast, but that’s not the case. There is plastic scattered all over the oceans of the whole planet. You find it even in the most remote regions, such as in the Arctic (North Pole) and on isolated islands of the Pacific.

What we see on our beaches is just the tip of the iceberg. Not only is there plastic floating in sea water, but massive quantities of it have accumulated on the ocean floor.

Plastic doesn’t float forever, and after a while, due to algae or animals clinging to it, it gets weighted down to the bottom. It’s the same thing that happens when a plastic carton fills with water and becomes so heavy that it no longer floats.

Christopher Kim Pham, a scientist at the University of the Azores, Portugal, is one of the authors of a study that aimed to find out where the plastic goes and how much there is on the ocean floor in European coastal waters.

The study was carried out at thirty-two sites in the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. It found plastic on the ocean floor in all these locations. There was even plastic in places 1,800 miles (3,000 kilometers) from the coast, in the middle of the Atlantic, and sometimes at great depth!

As Pham said, “The plastic got there before we did!”

How long does it take for plastic to decompose?

The decomposition time of plastic depends on many things: the type of plastic, the size of the piece, the environmental conditions (sun exposure, water temperature, currents), and the areas it has passed through or where it is found. For example, the plastics that end up on the ocean floor take a long time to decompose because of lower water temperatures and the fact that they are in low-light and less-eroded areas. In theory, because plastic is an organic (carbon-containing) material made from petroleum, it should eventually break down into carbon dioxide and water. But no one knows how long this will take, because no one has lived long enough to see plastic disintegrate completely.

ESTIMATED TIME IT TAKES FOR OCEAN LITTER TO DISINTEGRATE

Plastic straw: 200 years

Soft drink can: 200 years

Disposable diaper: 450 years

Plastic bottle: 450 years

Fishing line: 600 years

WHAT IS BIODEGRADABLE?

Biodegradable materials are those that break down due to the action of bacteria and other organisms, leaving nothing except for carbon dioxide and water (i.e., substances that exist in nature).

Plastic decomposes very slowly and can take many centuries to completely disappear.

The consequences of plastics in the oceans

When fish, birds, turtles, whales, and other species come across plastic in the oceans, it is almost always an unhappy encounter. There are three especially worrying situations:

1.When animals ingest plastics or microplastics that accumulate in their organs and tissues.

2.When animals are trapped and/or injured in nets, plastic loops, or other objects.

3.When plastics release the additives in their chemical makeup and the pollutants they have adsorbed from the sea.

Adsorption is different from absorption. Here, adsorption refers to how the molecules of a pollutant cling to the surface of a plastic.

Heartbreaking images

The internet and documentary films about the oceans often show shocking images of animals that have suffered the effects of plastic. It’s hard to forget these images.

1.Photographer Chris Jordan took photos of albatross chicks on Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean. They show the effects of a plastic-based diet fed to them by their parents. They did not survive. How does something like this happen?

It’s simple. The colors and shapes of plastic attract the albatrosses and other animals. And when plastic has been in the sea for a long time, it may be covered in algae or tiny animals and smell like tasty food. Albatross parents easily confuse it with food and, full of good intentions, collect it to feed their offspring. After a short time, the chicks die.

Many animals that ingest plastic end up dying of hunger. Why? Because even though the plastic fills up their stomachs and makes them feel full, they haven’t really eaten. So they die of starvation.