Читать книгу Plasticus Maritimus - Ana Pego - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMy beach (and how it explains a lot of things)

I’m a marine biologist. I’m not sure when I first began to have a preoccupation with plastics. There probably was no exact moment when I had a sudden insight. I don’t even remember if it took place on what I call “my beach,” though that would seem most likely.

My beach is only 650 feet (200 meters) from the house where I grew up. It is a special beach because it has a rocky area that creates lovely tide pools. At low tide, these pools full of sea water are a refuge for a huge variety of animals and plants.

Some people have a yard behind their house. I was lucky enough to have a beach two minutes away, the most incredible backyard anyone could have. At low tide, the smell of the sea was amazing and so strong that it wafted up the street to my house.

Every day, I’d arrive home from school, throw my backpack into a corner, and call into the house, “Mom, I’m going to see how the beach is doing!” And I’d head off. Going to the beach was like going to visit a friend to get a sense of how they were feeling.

I’ve always loved studying tide pools. See how beautiful they are!

Though I didn’t really realize it, going to check out the beach meant spotting a lot of different things:

Whether the tide was high or low (or was coming in or going out)

Whether the sand was the same as the day before or had changed (sand accumulates in different parts of the beach depending on the seasons and the tides)

Whether the sea was calm or choppy

Whether there was anyone else on the beach or I had it to myself

Montagu’s crab, or furrowed crab

(Lophozozymus incisus)

Snakelocks anemone

(Anemonia sulcata)

Spiral wrack alga

(Fucus spiralis)

Purple sea urchin

(Paracentrotus lividus)

Dog whelk

(Tritia incrassata)

Limpet

(Patella sp.)

On days when the tide was low, there was a path between the rocks to the next beach, and along the way, I picked up fossils or looked at the marine animals.

Now, I also pick up the garbage I find scattered on the beach.

My obsession with marine plastic resulted from a combination of different things. But the time that I spent in the water pools on my beach probably explains it best. It was there that I learned to love the sea. And when you love something, the most natural thing is for you to care about everything that’s related to it.

Why focus on ocean plastic?

There’s a long list of problems related to the oceans. Here are some examples:

Increase in water temperature owing to climate change

Problems related to overfishing

Sound pollution caused by maritime traffic

Chemical pollution (often invisible) coming from diverse sources, such as oil spills or untreated sewage

Animals and plants in trouble and needing help to survive

I chose ocean plastics because they represent 80 percent of the garbage in the oceans. All evidence points to a relationship between the presence of microplastics in the oceans and numerous health problems in both animals and humans. Algae, fish, and many other species are affected. And it is clear that humans are already suffering the consequences of contamination by this invasive species, ocean plastic.

Lots of problems need solutions

One positive thing about the time we’re living in is that we have a good understanding of the problems that need to be solved. This is a big advantage over other periods in history when there was less communication worldwide and when science was much less advanced. Today, if we care about the planet and about everyone who lives here, we can have a better understanding of what’s going on. Scientists study the problems and gather information and in many cases have already come up with solutions—and this is an enormous advantage. But things are not always resolved, are they?

That’s true, first, because there’s a huge array of problems to sort out; second, because even though the information exists, it doesn’t always reach people; and third, because people, institutions, or governments don’t all have the same priorities or are not doing their jobs the way they should.

This is why it is very important for us to take an active role. Being an activist means precisely this. If there’s a problem that we’re troubled by, and if we can see that this problem has serious consequences, then we need to recognize it and get down to work to change the situation.

The world can only move forward if we don’t wait for these problems to be resolved on their own or for others to resolve them.

It doesn’t matter how old we are, what our occupation is, or whether we think we’re on our own. There are all kinds of examples of people worldwide, people of all ages and backgrounds, who have become spokespersons for a cause. And there are also many examples of one person making a difference.

This book aims to turn you into a specialist in ocean plastic. It contains the basic information you need to have a good understanding of the problem so that together we can confront it in the best and most effective way.

In this book

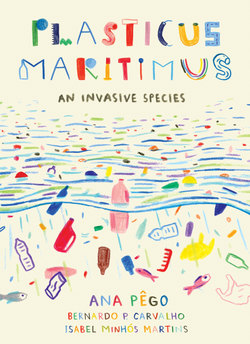

This book begins with a discussion of the role of the oceans in the life of the planet. It looks at how plastic is produced and describes the consequences that plastic garbage has for life on earth. It explains why I have decided to give ocean plastic a scientific name—Plasticus maritimus—and call it an invasive species.

The field guide to ocean plastic presents examples of the most common types of ocean plastic as well as the most exotic types I have come across. Throughout the book, you will hear about what people are doing to combat ocean plastic and how you can get involved.

I hope this book will encourage you to get to work: to refuse to use plastic that is unnecessary, to look for alternative solutions, to be inspired by the ideas that you encounter, and to come up with your own ideas. There are already many of us working on this issue, but we need an ever-growing network of people in order to get rid of the plastic in the oceans. Join us!

Has it always been like this?

Almost everything around us is made of plastic or of materials that contain some plastic. Today, we can live in a house with plastic floors and furniture, work on a plastic table with computers made of plastic, dress in plastic clothes (check the labels, you’ll be amazed), put on plastic shoes, eat food that comes packed in multiple layers of plastic, and eat and drink with plastic plates and cups. In many countries, even some toothpastes and face and body scrubs or exfoliants have plastic in them.

It’s normal to use plastic. So normal that we don’t even think about it. But it hasn’t always been like this. Today, we live a life of buying, using, and throwing away, a life that was unthinkable to people a hundred years ago. We have access to a huge quantity and variety of consumer goods and we are used to products that last for a short time.

Many of the things we use come in packages. Packaging is useful because it protects products, enables their transport, and provides information about them. However, it is common for products to be overpackaged to make the products look larger. In addition, products are often placed inside large polystyrene packages that are unnecessary. This is the case of the prepackaged fruit, vegetables, and meat that we buy in supermarkets.

It doesn’t make sense to return to the past, to the time when milk was transported from the countryside to the cities by horse and buggy. We’ve invented amazing things in the meantime and it would be foolish not to make the most of the technologies and materials that exist.

Yet it’s important to think about the consequences of our choices and decide when to buy or use something made of plastic. It may be a unique and useful material, but it has such huge impacts on the environment that we must use it consciously.

This cellphone is a dinosaur. It’s already four years old!