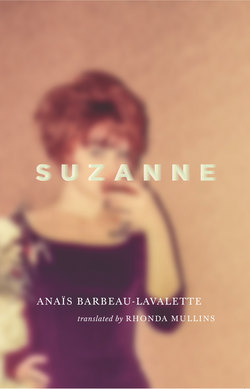

Читать книгу Suzanne - Anais Barbeau-Lavalette - Страница 30

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThis morning, you accompany your father, who is getting his hands dirty. He is in the second stage of dandelion picking. They have emptied the downtown of dandelions; now they are going to the edges of the country, where the city spills over.

Sitting beside him in the Bennett buggy, you set your shoulders square with the sky. Achilles likes things straight. When you hunch, his large hand whacks you on the lower back.

He says that Ontario French Canadians are people who stand tall. That’s what helps them survive.

Sometimes you purposely hunch so he will touch you.

The car moves forward, pulled by the horses, as rusty as the car itself.

You like driving with Achilles because he talks to you. No: he makes you talk. It’s not so much what you say that interests him. But how you say it.

He asks you to describe what you see. He makes you start over until the sentence is perfect. The best words, the best order, the best diction. Polished till it shines.

Even if you’re describing something dirty.

Today, Achilles stops the Bennett buggy in front of the Hole, a pile of mouldy, makeshift shelters. The smell of sardines and dried piss hangs in what is left of the air. Music – the Boswell Sisters? – crackles in the distance. A few scattered clotheslines stand watch over the rags of families in survival mode.

The Hole looks like it’s a thousand years old, but it’s new. The Hole is one of the country’s first slums.

Achilles parks his Bennett there and won’t let you avert your eyes. He wants you to look at it.

He wants you to find words you don’t know to describe it.

You say: wood, scrap iron, horror. You say: rat, laughter, music. And then: sad, wet, end of the world.

A child is walking barefoot through the mud.

You say: ‘Daddy, I want to leave.’

Achilles asks you what you’re afraid of.

He won’t budge until you figure it out. Your six-year-old mind tries to put your finger on what is scaring you.

The little boy holds out his hand to you. He wants money. You look down at your lap.

You say you don’t know where to look, that everywhere you look you make the misery worse, you make it more real.

The little boy is still holding out his dirty hand to you.

You grab on to your father, beg for his help. Which he denies you.

So you take the little’s boys hand in yours. And you introduce yourself using your school voice: ‘My name is Suzanne.’

The little boy pulls away from you, running off into the meanderings of the Hole.

Your father hails his old team of horses, which sets off again.

He is satisfied.

You have dipped your tongue in dirt.

You leave the Hole and those rotting in it behind you. But there is an aftertaste of shit and lives with pieces missing.

That’s what he wanted.

He wanted you to taste it, to feel sick to your stomach, so that you would do anything to not end up there.