Читать книгу The Devil's Paintbrush - André Brochu - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеEach house is an enigma, sheltering its own impenetrable share of the unknown. It is often an aroma, something about the shadows, the rumour of voices and laughter, songs and shrieks, the rustling of myriad lives. These things, and a thousand other bits of trivia, give each inhabited space its uniqueness. The roofs are imposing or discreet, essentially black with asphalt or tar, but retaining a hint of blue, red, green, or gray. They top masses of brick or wood pierced by windows that open dimly onto pallid interiors, forming watertight containers of life for a few people, sometimes for one, under a tranquil canopy of old trees.

In the houses live beings who are sheltered and free, who attend industriously to the small chores that mark the passing of existence. For it is elsewhere — in offices and factories — that they earn the right to subsist and be happy. Houses are there for the time they have left over, and for pleasure. There, they cook, wash dishes, make love, and raise a few candidates for the future who will, in turn, found their own homes. Houses beget houses, further sanctuaries dedicated to hallowed domestic life, or to selfishness, or to cultivating a couple’s delights and hatreds. Houses are nice. They’re tidy, redolent of well-tended property. We live and die in houses, there await the passage of time, limpid and eternal. If time stopped passing, stopped short, matter itself would vanish, leaving no trace in memory.

But in some houses — very rare — time stagnates. These are the dwellings of unfettered poverty. They do not elicit sympathetic attention, but simultaneously whet and repel the curiosity of passersby. Dilapidation. Filth. Usually, large families buzz about them, and sometimes they turn pretty spots, adorned with trees and water, into dumps. The Tourangeau house is like that. Blue, enormous, and hunched, it rises up halfway down the slope between the road and the water.

The river. At the foot of the lot, its current rises in a vast movement that, a little further along, turns back on itself, forming a large eddy. Lucie Tourangeau is quite proud of this whirlpool. She has nothing, yet the blessing of this reversing current is hers. Across the river, on Île Jésus, she glimpses mansions hidden in the greenery, lawns rushing down to the lapping rapids, and tells herself that, over there, the water flows in the orthodox direction, from southwest to northwest. The rich people across the way might envy her current.

There is also the drop-off, twenty-five metres deep, just off shore. It is deep enough to hold several houses piled atop each other. When she swims, Lucie Tourangeau pauses, upright, just above the abyss, and listens from within her own depths to the silence below. She communes through flesh and blood with the stony river bottom, urinates languorously into the dark water, and is fulfilled.

There is this bounty, and the public’s bounty: Lucie Tourangeau is a well-cared-for pauper. Swimming against the currents of fashion and comfort, she has no trouble feeding and clothing her nine children, endowing them an old-fashioned look in modern times, a distinguished air, overflowing with health — and great drive, too. They have a way of venturing freely out into peaceful territory, of confounding decorum. In spite of the public’s solicitude, the Tourangeaus are a feared tribe. Nice, of course! Well spoken — speech marred by carelessness, yet sprinkled with rare expressions springing up about the edges, manners that abruptly reveal indications of a proper upbringing — and then an utter, profound, spontaneous, incurable lack of distinction, inherited from their mother: La Lucie, whose name alone can make her peaceful neighbours sigh.

Sigh — that gangling beanpole, Dutch on her father’s side, Mohawk on her mother’s, that monument of pregnancies whose ideas are enough to make you laugh and grind your teeth, such a fright in her big rumpled dresses!

She lives with her string of boys and girls in a two-dwelling house by the water. The house must have been charming, once, beneath its fifty-year-old ash trees. No more. Among them, the ten occupants quickly transformed it to suit themselves. Three years ago, they acquired this unhoped-for lodging following a joint intervention by the mayor and the parish priest, and marked the event with various gestures of appropriation that have left spectacular traces. The front yard particularly is choked with debris of all types and sizes: unhinged bedroom doors, scattered shutters, old windows whose panes were shattered by the violent child, Fernand, and which have now been replaced by plywood. Not to mention the harvest of imported booty — tires, hubcaps, and road signs, collected during enthusiastic escapades — that has become a permanent feature of the domestic landscape. The property soon earned the unenviable label of “pigsty,” bestowed by a unanimous neighbourhood, and the value of adjacent properties plunged dramatically. To add to the disgrace, the sewage pipes and septic tank proved inadequate, and so an open stream now runs toward the river, scattering germs and odours in all directions. When wind stirs, discerning neighbourhood noses complain, “It smells like the Tourangeaus!” La Lucie has conscientiously notified the City, but her impecuniosity shelters her from quick action.

All in all, Lucie is a nice woman, courageous, kind, generous, and even beautiful, in spite of the menace of rapid decline common to the Amerindians. But you can see why her husband, a bohemian himself, stuck her there and went to live in the city in his studio on Rue Saint-Paul, where he makes enormous plush animals, each one more fantastical than the last. There, he consoles himself for having been ousted by his crop of offspring from first place in her affections. From a distance, he still considers her the queen of his heart — she who, until recently, kept peopling the world with new beings drawn from her entrails as if the act of giving birth was her life’s purpose.

She’s had seven children, all handsome and full of life, though sometimes a little short on health, despite appearances. This gives rise to vigorous illnesses: double pneumonias and very scarlet fevers that bring their victim to death’s door. Then three days after the priest has come, the dying one is splashing in puddles once again.

Seven children. But when the people across the street moved without leaving a forwarding address, or anything but two starving brats, Lucie, heeding only her heart and her passion for children, added them to her brood on the spot: a little girl and a wee rascal, adorably enchanting. Lucie has vowed to fatten them up and pamper them until she has erased all memory of their former existence as child martyrs. Tiny compared to their new brothers and sisters, Corinne and Stéphane exert remarkable yet subtle authority over them and are taking them great strides forward in vice and duplicity.

One afternoon, using a furtive scenario invented by Stéphane, Fernand (the violent one) and Bernadette (the youngest) secretly absconded with the magic jars that Lucie stores in her huge bedroom cupboard for use in her presentations. The containers hold fetuses at various stages of development. The Tourangeau children would never have dreamed of stealing such maternal treasures for their own amusement. Although you have to admit that in this case they had considerable entertainment potential. The halted lives, wedged into their glass prisons, almost lay bare the soul itself, which seems at one with the slender fingers jointed like a spider’s legs, and especially with the alien faces that appear to ponder the inconsequentiality of human decisions. Lucie uses them to explain that Life is preferable to all else, and that poverty — of which she is a shining example — cannot justify the slaughter of innocents in which modern savagery indulges. She has been a militant member of the pro-life movement for two years, finding in it a powerful means of self-actualization, as well as a chance to escape from the daily round of chores once in a while. Outside her immediate circle — they would never take her seriously, since nobody is a prophet in their own country — a natural inclination for humanitarian action allows her to exercise her apostolic mission, replete with high-sounding words and moving gestures. The little bundles of waterlogged flesh, suspended in formaldehyde, are always a tremendous success, especially with children, whose juicy questions often relate to their cartoon heroes. The contemporary imagination makes good use of intra-uterine esthetics in its depiction of typical physiognomy.

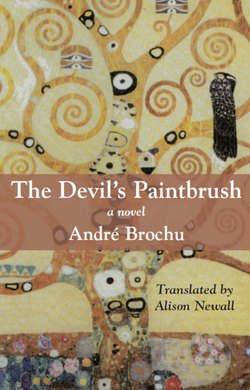

Arms loaded with the precious jars, Fernand and Babette (the youngest’s nickname) hug the wall of the house beside the hedge and take refuge in the old garbage pit, now bristling with devil’s paintbrush. Stéphane and Corinne await them there. Fernand stipulates that they have to be careful not to break any of the jars. That would be a catastrophe. They’ll just look and pretend to be abortionists and not touch anything. Lucie has told her children about the horrors of this diabolical action, hoping to instill a sound respect for life. Stéphane, having invented the game and cast the roles, will play the fetus. He sits down between Babette’s legs. She is younger, but just as tall and twice as heavy — a five-year-old giant. It is Fernand’s job to extract him, using a piece of garden hose as a siphon. Corinne plays the nurse. The sequence of actions to be performed seems complete, and now they’re eager to carry them out. Fernand clowns noisily, proud of his executioner’s role. The sturdy boy dislikes Stéphane, despises his intelligence and skill — weapons of the weak! Subconsciously, he is mainly resentful of the place Stéphane and his sister have usurped in his mother’s heart. The play-acting will let him get back on top, and, in his imagination, eliminate a secret rival.

“Shut up, Fernand! You’re going to get us get caught!” says Corinne. “Stop fooling around and be the doctor. I’m going to pass you the siphon. Are you guys ready?”

Babette growls yes. In spite of her age, the little girl can barely talk. Usually, she just sniggers or makes sounds that have no specific meaning. Stéphane’s head on her belly makes her giggle. She knows she’s the mother, and this huge baby is going to be sucked out of her through a little tube. It isn’t real, but it’s really funny.

“Okay,” says Fernand. “Let’s get started. Nurse Corinne, the siphon please.”

“Yes, doctor.”

Corinne passes the green plastic serpent to Fernand and, at first, he doesn’t know what to do with it. Then he stretches one end toward a jar and presses the other against Stéphane’s belly button. Stéphane shudders at the touch, then stiffens, seeming to gather himself up. He becomes even smaller and makes a strange hissing noise as he slowly starts to emerge from between Babette’s legs. Babette shakes with laughter as he makes his way toward the sun-flooded jars.

“He looks like a pickle!” says Fernand. Faced with this hilarious spectacle, he can’t stay in character.

“Shut up!” Corinne protests. “You’re going to wreck everything.”

Stéphane inches toward the jars with small movements of feet and buttocks, still wearing the sorrowful expression he’s had since he starting playing the part of the evicted child. But then he stops, exclaiming, “Darn! We’ve got to start over. I forgot the most important thing.”

“What?”

“When you’re taking a baby out, it doesn’t just come. It’s got to fight, make a fuss.”

Corinne, who understands, bursts out laughing. Fernand and Babette laugh too, a little late.

“We’re starting over. You, Babette, squeeze me a little with your legs like you don’t want to let me go. Hey! Not so hard, you bloody savage! You’re smothering me! Doctor, you stay in character or I’ll make you eat those pickles.”

Any outside observer would find this David-to-Goliath threat a little strange.

They start over. With his head on the girl’s belly, Stéphane twists around for a good spell as if he’s being torn in different directions while his pretend mother chortles with glee. Excited, Fernand dances in front of the two, so entranced that he ends up wetting his pants. When he realizes what has happened, he bursts into laughter.

“Hey! I peed my pants!”

The others abandon the game instantly, seized with noisy hilarity. Fernand is delighted to be the centre of attention. He wrings the wet cloth with his hands, miming grotesque gestures and parading his enjoyment. Then, suspecting a mocking undertone, his mood suddenly changes and, furious, he sends the jars flying away with great kicks. One jar breaks, rolling its contents into the grass.

This, of course, puts an end to the fun. Alerted by their yells, Lucie descends on them. She is as upset as if she’d lost a child, and, with a loud display of despair, even raises her hand to Fernand, who fends her off with a spectacular tantrum. Stéphane and Corinne — easily overlooked among the others, and especially indulged by their adoptive mother — grow quieter than ever and produce the demure smiles of well-behaved children. Fernand denounces them, but in vain. Everyone is against him, and he gives way to wracking sobs.

Lucie is completely beside herself. She runs out to buy a padlock before the stores close, determined that, from now on, her precious jars will be kept safe from such profane curiosity. When she gets back, though, she is plagued by a fear of losing the key. She is unused to these tiny metal contrivances — for Lucie, the best guarantee of happiness is a house that is open to all comers — so she decides to leave the key on her night table and vows to check regularly to make sure it’s still there.