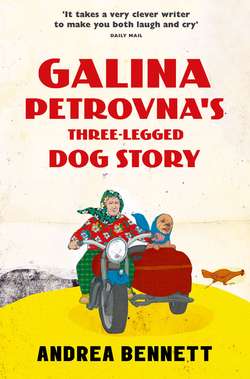

Читать книгу Galina Petrovna’s Three-Legged Dog Story - Andrea Bennett - Страница 8

1 A Typical Monday Afternoon

Оглавление‘Hey! Goryoun Tigranovich! Can you hear me?’

A warm brown hand slapped on the door once more, its force rattling the hinges this time.

‘He’s dead, I tell you! He’s probably been eaten by the cats by now. Four of them he’s got, you know. Four fluffy white cats! Who needs four fluffy white cats? White? Ridiculous!’

‘Babushka, can you hear any cats mewing?’

The two ladies, one indescribably old and striated and the other only mildly so, waited silently for a moment outside the apartment door, listening intently. Tiny Baba Krychkova bent slightly to put her ear to the keyhole, closed her eyes and sucked in her cheeks.

‘I hear nothing, Galia,’ she replied after some moments.

‘So that’s good, isn’t it, Baba? That means that Goryoun Tigranovich has probably gone on holiday to the coast, or perhaps to visit friends in Rostov, and has left the cats with someone else. And that means he isn’t lying dead in his apartment.’

‘But Galia, maybe they’re all dead! The cats and Goryoun Tigranovich! All dead! Maybe they found him too tough to eat and they starved! It’s been several days, you know.’

The older lady’s face crumpled at the thought of the starving cats and the dry, wasted cadaver of Goryoun Tigranovich, and she began to sob, rubbing a gnarled red fist into her apple-pip eyes. Other doors began to creak and moan along the length of the dusty corridor, and slowly other grey heads studded with curranty eyes bobbed into view, to peer curiously down the hall towards the source of the noise and excitement. A vague hum stretched out along the length of the building as the elderly residents rose as one from their afternoon naps, whether planned or unplanned, to witness the drama unfolding on floor 3 of Building 11, Karl Marx Avenue, in the southern Russian town of Azov. Galia sighed, and offered her handkerchief over, and made compassionate tutting noises with her tongue.

‘Baba Krychkova, there is nothing we can do out here in the hall. I am sure that Goryoun Tigranovich is in the best of health. He’s such a sprightly fellow – and a regular traveller, you know. Just last month he was in Omsk.’

Galia didn’t trip over the words, pronouncing them firmly and evenly, but to her own ears they sounded unconvincing: the last time she had seen the gentleman he had resembled a piece of dried bark dressed in a suit. ‘I am sure I saw him last week, down at the market, and he was buying watermelons. People who buy watermelons are not about to die: they are enjoying life; they are robust, and hopeful. Watermelons are a sure sign. He was probably taking the melons as a present for whoever he has gone to visit. I am confident he will be back soon.’

Melons or no, Goryoun Tigranovich was a very private person, and he would not welcome being discussed in the hallway by his entire entourage of elderly neighbours. Galia tried to encourage the older lady to go home.

‘Why don’t you go and have a nice cup of tea, and I can bring you one of my home-made buns. You’d like that, wouldn’t you?’

The older lady’s face did not change, but her tiny watery eyes were on Galia now.

‘And if we still haven’t seen him by the end of the week, we’ll ask if the caretaker knows where he’s gone.’

‘He promised me a marrow, you know,’ said Baba Krychkova over her shoulder, as she shuffled off down the corridor. Now there, thought Galia, is the real root of the problem: upset over an unfulfilled vegetable promise.

‘I can give you a marrow, Baba Krychkova, and mine are just as tasty as Goryoun Tigranovich’s.’

Baba Krychkova shrugged in a dismissive manner and shut her door, leaving Galia little choice but to cluck her tongue, shake her head gently and disappear into her own apartment. Boroda got up from the box under the table and greeted her with a gentle wag and a beautiful, elongating stretch.

‘The grace of dogs,’ thought Galia, ‘is in their complete, friendly laziness. And the fact that they can’t speak.’

Unlike many of her neighbours, and all her friends at the Azov House of Culture Elderly Club, Galina Petrovna Orlova, or Galia for short, almost never cried. While they glistened like sweetie wrappers chewed up by one of Goryoun Tigranovich’s cats, she sat squarely on her chair, quietly bronzed, her muscular hands resting in light puffy fists on her floral-clad thighs. She listened attentively to the complaints of the others, sighed and tutted gently as they recounted tales of lives that were hard. Galia considered that she herself lived in the present, and rarely reminisced. Her concerns included her vegetable patch, good food, complicated card games and her friends. She took pride in her town and her region, and she would certainly defend her motherland against any sort of criticism that wasn’t her own. She was not what one might call a sentimental person.

However, even the most unsentimental among us have to have something or someone and, in the autumn of her days, the source of Galia’s completeness, and the well from which she drew her compassion, her patience, her certainty and her rest, was neither the church nor alcohol, nor gossip, nor gardening: the source of her calm was her three-legged dog.

The dog had a narrow face and graceful limbs tufted with wiry grey hair. Her dark eyes tilted over high cheekbones, recalling, perhaps, some long-lost Borzoi relative waiting on the eastern plains, under a canopy of frozen tear-drop stars. That was Galia’s initial impression when she first saw the dog from a distance outside the factory, when she didn’t have her glasses on. On closer inspection, however, she could find little evidence of blue blood in the mutt: limp-tailed and apologetic, she had taken up residence under a particularly rancid snack kiosk, and was scavenging for food. Galia steadfastly ignored the beast. For five days, Galia pretended the dog wasn’t there and turned her head slyly as she passed to and from the vegetable patch. And then on the sixth, she saw the dog trying, with her lone fore-paw, to extract a stub of bone from under the piss-stained kiosk. Poor dog: only three legs. It reminded Galia of a feeling, like a vague sniff of something or someone that had been a long time ago and long-since departed. Something she wanted to hold on to, but could not even touch. The old lady watched the dog and sighed. The dog’s ears pricked at the sound, and she stopped scrabbling. There was a moment’s breathless pause in the bustling afternoon, and a long dark-brown gaze was directed straight through Galia’s woollen cardigan and into her heart. Their fate was sealed, whether she liked it or not.

Galia had carefully extracted the stub of bone with her penknife and given it to the dog, who accepted it between gentle white teeth. As evening drew on, the dog followed Galia home at a polite distance, ignoring vague shooing noises that emerged, half-hearted as sun-kissed bees, from Galia’s throat. The dog sat patiently outside the apartment door as dusk crept down the hall, and was still there when the ball of the sun rose on the horizon and the blackbirds broke into song. After a night of deep meditation, Galia relented and opened the door wide. In slid the dog, to sit calmly under the kitchen table, looking about her with brightly inquisitive, almond-shaped eyes.

‘Dog lady, what shall we call you, eh? I wonder if you’ve had a name before? Probably Fido, or Shep, or Sharik or something else ugly and completely unsuitable. Well, no matter. Look at you, handsome lady, with your cheekbones and your pointy beard: we will call you Boroda, the bearded one. That’ll do for us.’

And Galia called the dog Boroda, in recognition of her fine, pointy beard.

* * *

Sometimes, her broad arms thrust into a great cool bowl of pastry, gently kneading the gloop into the tastiest morsels this side of Kharkov, Galia’s thoughts turned to the past. For all she insisted she lived in the present, as she got older, she needed, occasionally, to remember. Not to look for answers or mend long-forgotten quarrels, or cry and miss and reminisce, but to remind and reassure herself of who she was and where she’d come from. Rolling the pastry out into huge snowy sheets, ready to cut into hundreds of leaves to be filled, crimped and boiled, Galia sweated in the heat of midday, the small salty drops occasionally dripping into the expanding mixture below. Her brow grew wet and dark as the culinary process proceeded and memories crowded around her, and Boroda receded further under the table, claiming her cardboard box in the darkest, coolest corner.

Galia had lost her parents, her virginity and many of her teeth during the Great Patriotic War. She preferred not to relive any of those events. In a space of weeks, that seemed like her whole lifetime – but also no time at all, as time had stood still or ceased to exist or just exploded – she had grown up. This was a few weeks that, in her memory, she condensed into something untouchable and shut up in a black box. Open the box, and all you could hear was a never-ending scream and all you could see was a giant mechanical hand scratching dry bones, and all you could feel was the freezing wind of the steppe and a raging hunger. A box of memory that denied the existence of the sun, animals, trees, laughter or childhood. A box she rarely dared delve in to.

This same era of numbing change, hurt and sacrifice also brought her – like a particularly big and difficult baby under a gooseberry bush – a husband. Just like that! Again, she didn’t like to brood on this fact, but she could not, for the life of her, remember how it had happened. She had been a slight girl then, with milky skin and frizzy blonde hair that she hid under a greasy khaki cap. Entirely alone and so scared she couldn’t recall her parents’ faces, or her own, she had somehow got slung together with Pasha and his field kitchen and a band of stragglers, way behind the front line, with Victory in Europe a few weeks off. Pasha: a little weak, a little lazy perhaps, with liquid brown eyes and a smile as wet as tripe. He kept the black box out of her sight for a while. He smiled and there was a possibility that laughter had, at some point, existed, and had meant that something was funny, not that someone was mad. He felt like a ballast, keeping her feet on the ground as the world shook and the war ended around them.

‘Ah, too bad, butter fingers,’ Galia muttered to herself as the last of the vareniki slid from her tired fingers and plopped with a puff of flour on to the floor. Boroda extended her noble neck a few inches from her box under the table, politely indicating that she would happily clear up the fallen morsel if Galia would permit.

‘Go on then, lapochka, you may as well have it. Do a good job mind, clean it all up, my bearded lady.’ Boroda’s sharp pink tongue lapped up the mixture in seconds and her tail thumped gently on the wall of the box.

‘No gulping, mind – even street dogs don’t have to gulp!’ Galia teased. Boroda flicked her a grateful glance and continued licking the floor clean with a great deal of care. The dog’s needs were simple: bread, potatoes, occasional scraps of fat and bits of fruit were her staples. She, generally speaking, would not have dreamt of begging for food from the table, but if it fell her way that was a different matter. In her turn, Galia would not have thought of putting a collar around her neck. They were equals, and chose to be together in companionable quiet. There was no constraint, and new tricks were not required. The spillage all cleared up, Boroda licked her lips and then the tip of her long thin tail, and settled down to sleep.

Galia was prevented from returning to her reverie by the sudden bleeping of the phone, which brought her huffing into the hall. ‘Oh for goodness’ sake!’ she muttered under her breath, ‘is a body to get no peace in this world?’ and then loudly ‘Hello! I’m listening!’

‘Galina Petrovna, good afternoon! It’s Vasily Volubchik here,’ said a confident but somewhat creaky voice.

‘Yes, I know,’ replied Galia with a sigh, and then, fearing she sounded rude, ‘and how can I help you, Vasily Semyonovich?’

‘I’m just checking that you’re coming to the meeting this evening, Galina Petrovna. We have a very exciting agenda, I assure you: the Lotto draw, and … er, oh, er, bother, what was it? I’ve forgotten the most exciting thing, er—’

‘Yes, Vasily Semyonovich, I’ll be there. I am sure it will be most entertaining. Goodbye!’ and Galia replaced the receiver with a slight frown. Vasily Semyonovich Volubchik was nothing if not determined. He had been phoning every Monday for at least three years to ensure that she didn’t forget to attend the Elderly Club. And every week he promised her something exciting. So far, the most exciting event hosted by the Elderly Club had been a talk on fellatio by a local enthusiasts’ group. Or did she mean philately – Galia could never recall the difference. But it had not been exciting: merely diverting, in her estimation.

She padded down the hall in her soft white slippers to wash her face and neck. She had a feeling that the evening was going to be dull. Looking back later, she couldn’t quite believe how wrong this feeling had been. She had no presentiment of how her life was about to change. People often don’t.

* * *

‘Straindzh lavv, straindzh khaize end straindzh lauoz, straindzh lavv, zat’s khau mai lavv grouz …’

On the east side of town, in a square box of a room with orange walls and a shiny mustard lino floor, a youngish man intoned the words of his beloved Depeche Mode without a recognizable tune. He was wearing some sort of uniform that was very clean, but still smelt to others around him of something not quite savoury. The man was making busy, precise preparations under a bare sixty-watt bulb as the sun set outside, unnoticed. His black nylon trousers, crease-free and firmly belted, sparked small currents against his thighs that made the black hairs there stand up as he moved. His regulation blue shirt was neat and pressed and tucked in snugly all the way around. It made taut pulling noises as he reached to comb his hair, which he found minutely satisfactory. He had shaved carefully, including his neck and that part of his shoulders he could reach, and had fully emptied his nose into the basin (down the hall on the left, no, second left: first left is the room of the violent alcoholic – well, one of them). He had cleaned out his ears with a safety match, and the match had then been safely placed in the bin – not in the toilet, as had happened once, by accident, when it had bobbed about in the yellow-brown water for several days, disturbing him greatly to the point where he couldn’t sleep. For that matter, a match had also once been carelessly left on the bedside cabinet. But only once. The match problem had been overcome and Mitya’s will imposed on the small woody sticks and their sticky pink heads. Now they always went in the bin, immediately, and he slept well.

These things he did every day, in a set order. Or rather, every evening. He turned over the cassette – Depeche Mode, Music for the Masses – as he did every evening around this time, and pressed play with the second finger of his right hand. He inhaled deeply and closed his eyes as the music began. He envisaged the night before him, and emitted a satisfied snort, quietly, just for himself.

Mitya was thorough. He took pride in being thorough. Thorough and careful would have been his middle names, he thought, if his middle name hadn’t been Boris. He frowned and paused with the boot brush poised in his hand. The thought of his middle name spoilt his mood as a bark spoils silence, and he shuddered briefly in the shadow of his thoughts about Mother. There were things he held against his mother, and his middle name was one of them. A drunkard’s name, a name with no imagination: a typical Russian name. His left eye twitched slightly as he aimed the boot brush at a mental image of his mother hovering near the door, and slowly and deliberately pulled the trigger. Her green-grey brains spread out across the orange wall as Dave Gahan hit a rousing chorus and Mitya felt a tremble shoot from his stomach to his groin. Life was sweet. He had his order, he had his job, and in this room on the East Side, he was in control of his own affairs. He was Lord of all he surveyed.

There was a muffled click in the hallway, and Mitya froze, sensing trouble. He was not mistaken: a thumping beat suddenly vibrated his orange walls, snuffing out his tape like a candle in a snow storm. He lowered the boot brush and bit his lip. His neighbour, Andrei the Svoloch, was hosting a party, again. Soon there would be girls with too much make-up, girls with too much perfume, girls with skirts impossibly short and tights with ladders reaching up with clawing fingers towards their unmentionable parts. Girls: his neighbour was a success with them, it seemed. The younger, the better, according to Andrei, although Mitya always tried not to listen whenever his neighbour opened his ugly, tooth-speckled mouth. Mitya violently disapproved of Andrei, and his girls. He frowned at them from around his door, and when they laughed, he closed the door and frowned at them through the keyhole. They came out of Andrei the Svoloch’s room to go down the hall to the stinking shared toilet, and then he sometimes frowned at them through the keyhole of the toilet too, just to make his point, although this always made him feel bad afterwards. He didn’t know why he did it. It wasn’t like he found them interesting. It wasn’t like he wanted to see them at all. They were just hairy girls, after all.

Mitya’s view was that girls, and women in general – females, to use the technical and correct term – were a distraction. Men should keep their eyes on the prize and their wits about them. Girls were for when the fight was over. Or nearly over, as Mitya’s fight would never be over, fully. He knew that if he ever got in the position of being in physical contact with a girl, he would make sure that she knew where she was in his order of priorities before any actual physical contact ensued: somewhere near the bottom, way down the line after work, eating, sleeping, beer, going to the toilet, Depeche Mode and ice hockey. Oh yes, he’d show her. She’d realize how lucky she was, to be in physical contact with Mitya. One day. When he had the time. When he met the right one.

Mitya’s boot brush was still poised in his hand, one plastic-leather boot shiny, the other slightly dull. He collected his thoughts, pushed the girls firmly to the back of his mind, in fact out of it completely, and polished the dull boot with a frenetic stroke that turned his hand to a blur and made his neatly combed hair vibrate like a warm blancmange on a washing machine. When he had finished, the boot gleamed and small beads of sweat stood out on Mitya’s forehead. He folded a piece of tissue twice and blotted away the small drops. His arm ached slightly, and his heart was beating faster.

With satisfactory boots in place, he collected his wallet, keys and comb, and indulged in a last look around the room. Everything was in its place under the glare of the bright single bulb. He was out of here, and it was going to be a long night. He felt big, and enjoyed the noise his confident footsteps made stomping on the floor. He was a man on a mission, a man with a plan. He was important. The only cloud on the horizon, so to speak, was his bladder, which was now painfully full.

In the hall, Andrei the Svoloch with his hateful dyed hair and cheap cologne was leaning against his doorway, smoking a cigarette with one hand and rubbing the thigh of what appeared to be a schoolgirl with the other.

‘Hey Mitya, off for another night on duty? You’re so fucking dull, mate! Why don’t you join us for a drink? Come on – have a look at what we’ve got on the table? Maybe you want some?’ Andrei slid his hand right between the schoolgirl’s legs and she squeaked.

Mitya winced, but despite himself, he glanced into his neighbour’s blood-red room. It was a scene of hell. There were women everywhere: draped over the divan, curling over the TV, straddling the gerbil cage.

‘I’m going to work, just as soon as I’ve had a piss,’ he muttered, and stomped down the corridor. Turning on a sudden impulse at the toilet door, he bit out the words, ‘You need to clean this toilet, Andrei. It’s your turn. I did it the last four times. I’m not doing it again!’

Andrei the Svoloch laughed, displaying two rows of stumpy yellow teeth, and pushed the schoolgirl back inside the red room, closing the door behind him with a hollow thud. Mitya pushed hard on the toilet door, and his nose connected with the back of his hand. It was locked, again.

‘Son of a bitch.’

His swollen bladder would not be denied. The strain of keeping the pee in was bringing a film of sweat to his smooth upper lip. He had been periodically waiting to use the filthy toilet for over half an hour but every time he gave up and went back to his room, the cursed toilet occupant would come lurching out and be replaced by another incontinent before Mitya could get back down the corridor. So now he had to wait, and risked leaning on the wall next to the violent alcoholic’s door, his slim legs tightly bound together, hands clenching and unclenching. He hammered on the door again.

‘Come out of there you stinking old tramp! I’m going to call the skoraya – you’ll go to the dry tank!’ Mitya really, badly, needed to pee.

The door opened slightly, and in the festering half-light a peachy soft face looked out at him, hesitantly. After a moment the door opened wider on its squealing hinges and out stepped, not the stinking old alcoholic with vomit down his chin, but an angel come to earth. Mitya gasped and felt a small pool of saliva collect in the corner of his mouth and then trickle gently on to his chin. He had never seen a girl so beautiful and so perfect. Blonde hair framed a delicate face with apple cheeks, a small freckled nose and eyes that seemed to stroke a place deep within his stomach. And here she was, in the stinking bog, with a twist of yellow toilet paper stuck to her perfect, peach-coloured plastic slipper.

‘I’m sorry,’ she lisped, looking up at him through gluey black lashes.

‘No! Ah …’ Mitya wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. ‘I’m sorry, er, small female. Let me!’ and he held the wobbling door open for her as she slid through the gap between it and his underarm. ‘I didn’t know … I thought you were the old man – from up the corridor. He spends … hours in the … smallest room.’

‘Jesus, I’m surprised he’s still alive,’ joked the perfect angel with a wink.

Mitya felt something twang deep within him, like a ligament in his very soul stretching and snapping, never to be repaired. She turned slowly and swayed, tiny and ethereal, up the hallway towards the end room, and then hesitated, looking back at him from the doorway.

‘Who are you, beautiful?’ Mitya blurted, without meaning to make a sound, without knowing his mouth had opened, without giving his tongue permission to form any words at all.

‘Katya,’ she said, as if it was obvious, and she vanished behind the farthest door. The click of the latch struck Mitya like a punch in the face, and he gasped.

He took a long, slow piss and was struck by the thought that she, the angel, had been seated where his golden stream of warm pee was flying and foaming, just a few moments before. He shuddered and then, despite himself, leant down towards the toilet and could just make out a trace of her scent among the other odours rising from the dark bowl, the floor and the bin. Her scent, the musky scent of an angel, was subtle but powerful. Another hand rattling the door handle pulled him from his reverie. He pushed his way out of the cubicle, past the wobbly old man who roared something indecipherable but crushingly depressing at him, and made his way down the stairs and out to his van.

‘That my life should come to this,’ he thought, and aimed a ferocious kick at a passing tabby cat. He missed it by a wide margin and lost his balance for a moment, grabbing hold of the hedge to save himself and trying to ignore the muffled laughter bubbling from a bench behind it: a bench laden with small children and elderly hags, of course. ‘Females, children: nothing but trouble. I’ve got my work,’ he muttered to himself, and brushed the leaves from his shirt, ready to march off. As he did so, a butterfly bobbed up from the depths of the hedge and collided with his nose, making him flail slightly. Again muffled laughter scuffed his ears.

‘What are you doing, sitting there, cluttering the place up? Haven’t you got work to do?’ he spluttered hoarsely over the hedge.

The babushkas looked at the small children and the small children looked at the babushkas, and then they all began giggling again, tears streaming down their cheeks.

‘There, there, Mitya, on your way,’ croaked a sun-kissed face pitted with tiny, shining eyes.

‘Idiots. Geriatrics and idiots. You’re no better than rats, laughing rats,’ scolded Mitya, but not loud enough for his audience to hear. He turned on his heel towards the setting sun, and his shiny van that glinted in its rosy rays. The night was young.