Читать книгу Strip - Andrew Binks - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOne

A dancer’s fingertips—etched with a language that is no longer decipherable—tickle space, trace its volume, press, pull, contract, constrict, until they touch, grasp, hold and balance, shift what is on and off balance. They retreat, release, flick, dab. At careless times they graze. Graze nipples. Trace filaments across the skin. They touch the sternum and search for the heart.

A slammed door echoes up this stairwell from the floors below. Am I naked underneath this bedsheet? Is there bleeding? Blood. Reassuring. It means I still have a heart. They say it’s in our blood, this new disease. So far, they say, hundreds have died because of it. And my balls ache. My lip throbs. I taste the warm blood and my saliva mixed with something salty. There must be tears; I can barely see. There must be tears. If I had something in my stomach I would vomit. I remember Kent said our New Year’s resolution was to make 1983 our year. “Here’s to you and me in ’83,” he said. Helluva year it’s turning out to be.

Everyone has a Daniel, and, with luck, you’ll have him early on, to break your heart to pieces and then get over it. Never make the same stupid goddamned mistake again. Funny how you can talk yourself into thinking the road less travelled will be a noble trip. I tripped on the road less travelled.

I haven’t thought much about him recently, not his sharp chin or his Adam’s apple with the tiny cleft of stray whiskers that his razor couldn’t reach, or his long nose extending down from his forehead, making him look like the distant relative of the black and white television test-pattern Indian. He was superb and perfect, and he knew it. Someday someone might be inspired to stage a full-length ballet about nothing more than his eyebrows.

In this stairwell, in this light, Daniel is no more than a flicker. Through him I have come to understand lust, désir. Through Kent—love, amour. Lust singes the hairs on your hand, and can just as easily bite them with frost. Lust can kill quickly. Love tears your world asunder, then leaves you to die on the battlefield. But if I have to blame anyone (that is, anyone other than myself) I would start with Daniel. I could blame Kharkov, too, who brought in Daniel as a guest répétiteur at the end of our tour.

Montreal, our last stop on the homestretch of our first national tour as a big-league company. And 1982 was the Company’s year; we premiered the full-length Prokofiev Romeo and Juliet. We were exhausted and bloated from too much road food. The ballerinas were thick around their middles—even the anorexics were struggling—from endless health muffins and Caesar salads with house dressing hold-the-croutons-in-the-name-of-the-diet, and late-night post-performance carrot cake, or the great fatigue fighter, chocolate, in its many evil forms. Cigarettes were no longer keeping the addicts thin. We ignored our colds and our injuries—women taped their toes, wrapped their ankles, and rinsed the blood from their shoes. Men danced through pulled groins, shin splints and torn Achilles tendons. We were sick from drafty buses, drafty hotel rooms, drafty rehearsal halls and each other. A few sought refuge in chamomile tea, steamy showers and naps. In the midst of it all I, too, needed a pick-me-up.

This malaise, this touring burnout didn’t stop me, or anyone else from trying to impress the arrogant fuck, Daniel Tremaine, Montreal’s ballet wunderkind, the teacher and choreographer you went to if you wanted to win a medal at a ballet competition. Deep in Place des Arts in the bright rehearsal hall, cavernous ceilings, mirrors for miles, Kharkov announced, “Monsieur Daniel Tremaine will be giving us company class while we are here in Montreal.” Giving us? (Kharkov only took class in December when he faked his way through Drosselmeyer in The Nutcracker. Even then he usually just fumbled his way through barre.) Kharkov was nervous about impressing Montreal. Daniel would be his salvation. I looked around the studio. Some dropped their heads, pretending to limber their necks, others caught my eye. Some rewrapped their warm-up gear, leg warmers and sweaters, placing them strategically to hide the extra pounds.

Daniel Tremaine, the legend. People had compared him to Nijinsky, said he was built more like a bird than a human. But it didn’t stop his very ethereal body from betraying him; as he rehearsed an understudy for Montreal’s Conservatoire’s production of Swan Lake in Glasgow, he tore his Achilles, badly. Therapy went well, but he fell on some stairs when wearing the cast, and ripped the healing, the muscle and the skin, even worse than the original injury. His dancing career went kaput, but it hasn’t stopped anybody from wanting a piece of his greatness.

I tried to take it in stride as Daniel stooped—all six-foot-three of him—the top of his head, his thinning crown, next to my crotch, correcting my line and adjusting my instep. Oh sure, I have been nervous to the core with each new coach, teacher and choreographer, but when he touched me that first time, it hit me like the February wind at the corner of Portage and Main; my breath was shallow, my heart frappéd inside my rib cage, my ears rang and my vision went dim. I squeezed the barre, inhaled and fought a sudden numbness in my thighs. Like I said, it is the kind of attraction that will eventually destroy you.

He ignored me the rest of the class, thank God, but I couldn’t stop looking at those big hands that had touched me, the broad feet that had walked in my direction, the same feet that had danced all the great roles at so young an age on international stages, and at the way he flicked his famous wrists as he dreamily explained something into the air. I suppose that blasé, unimpressed look was how he got dancers to push themselves; the dancer’s ego is a frail and determined thing.

After class, in the bright hallway, while the others wandered ahead, I sensed him behind me and though I wanted to flee, something inside shouted, Stop for God’s sakes! Linger! And I listened. Daniel Tremaine stopped me with a touch to my elbow. “You have a nice line,” he told me, then he dropped his voice, “but the Company is destroying your technique and your body.” Then he put his hand on my shoulder, looked into my eyes and smiled, daring me to be shocked, “You ’ave a nice ass,” he said.

It seems my heart, as a muscle—pounding out beats and measures—is hardwired to that muscle between my legs. I had never felt so obvious. But I had never met a Daniel Tremaine. “Thank you.”

“Would you like some private coaching?” But I couldn’t speak. “I mean here, after class?”

Was I the only one who noticed the upper right corner of his mouth twist when he spoke English, and how it was met by a twitching at the corner of his right eye—as if it was painful to speak?

The rest of the day I wandered the tight neighbourhoods of the plateau, narrow streets of walk-ups pressed in on top of each other, iron stairways extending to the street, all punctuated by small cafés. But any place I came across seemed empty unless I could imagine myself there with him. My mind dipped in and out of what a professional coaching session with this man would involve—Daniel Tremaine having his way, a million different ways, with me. Why me? Second soloist? And only then, to fill the ranks.

After class the next morning, I lingered while he talked to his fawning fans—mostly Company members who would have killed for a coaching session—and a few notables such as the mayor and dance critics who were observing class. Daniel was a national treasure for Montreal. I continued to stretch until the room thinned out.

“Why don’t we start with some jumps; I can see you are a jumper.” This was true, although being a good jumper means you have to work on the weaknesses, and it forced me to perfect my turns. So I started with simple changements, to get some real height and momentum—and to hopefully impress. He stood close and calmly placed his hands on my shoulders, pressing against my lift, a logical action, but then he told me to stop. “Do you know what you’re doing?”

“Changements?”

“Your fifth position is forced.”

“I’ve always done it that way.”

“How are your knees?”

“Tender, but…” One of Martha Graham’s principal dancers told us we would never have a day without pain until we stop dancing. I had lumped all of my aches and pains under this noble disclaimer.

“You’re forcing your fifth.”

“The Company likes it that way.”

“Why?”

I paused.

“See, you have no idea. Do you think people in the audience are going to notice? No, of course not. It hurts me to watch. I mean, your jump is good enough to distract you or anyone else from your bad technique. Your knees must stay over your metatarsals. Does that not make sense?”

I just stared at him. Of course he was right but it’s like smoking, you know it’s bad for you, but…

“Are you listening to me? Stop staring. Your knees are made to bend forward, not sideways. Turnout originates from the hip. Why are you forcing your fifth? Jump, in first, and do not force it.”

As I jumped he walked around me, placing his hand on my lower back, on my stomach, on my upper chest. “How does that feel?”

I could have really told him, but all I said was, “Off balance.”

“Of course. The rest of you will have to get used to doing it properly, not overcompensating. Soon it will be easy. Soon you’ll understand a sauté.”

We worked on several sequences from corner to corner, a bit of “Bluebird” from Sleeping Beauty, but to do it properly would be another story. Daniel walked beside me as I moved, occasionally taking my hands and throwing them skyward. “Think of your landings. Think of the in-between.” But soon my legs turned to rubber. Why the hell were we doing a variation no one would ever give me a shot at?

“I want you to think of all of this tonight, when you sleep. I want you to see your body rearranging itself, changing the foundations, shifting to its core. But don’t be mistaken, this won’t happen overnight.”

I left Place des Arts and vowed to keep my mouth shut as far as Daniel Tremaine was concerned. I had a hot bath, a nap, strong tea and an early dinner and went for Company warm-up. All I could think about was his firm touch. I worried that my dancing would be sloppy, but I was light. I was nimble. I was fuelled by something unexpected. The evening flew.

The next day, in class I became aware of others. They must have known about the coaching. I stayed at the back.

After, I lingered again, and when the groupies had dissipated Daniel approached me. He rolled his eyes at the departing stragglers. “Did you think about what I told you?”

I nodded, but my voice caught in my throat.

“Good. Let’s learn a bit of Le Spectre de la Rose,” something the Company was planning as part of next season. Again, a long shot for me, or was it? He walked me through the first bit, showed me the choreography, miming everything on a small scale as if having a conversation with himself, complete with arm movements. Soon I was flying across the studio. We worked mostly on the entrance and the grand jeté, and the grand jeté en tournant, but he seemed more concerned with my arms. Then he took hold of my waist on each jump, lifting me beyond what I was capable of. As I focused on the ceiling I’m sure he was focused right bang on my crotch. This required the utmost concentration.

Finally, I came to rest on terra firma. I searched his expression to decipher what he thought of my jumps. But I was preoccupied with the why of this. Why was he coaching me? Had Kharkov requested it? Was I due for another promotion? Or was it rather what I suspected—did he have, as my friend Rachelle liked to say, his compass pointing in my direction? I couldn’t tell.

“Your legs are now throwing your arms off. You have to take risks now, and the arms have to go higher. Everything has to go up. Do you understand? You might as well be doing this with a walker. And for God’s sake, do something with your eyes; they’re absolutely blank. Look a little like you are enjoying it.” But I was terrified. And I wanted so much to enjoy it. To be coached by one of Canada’s great teachers, to imagine that one day “Bluebird” and Le Spectre de la Rose could be mine, was too much.

“My back?”

“Your everything.”

I didn’t have the strength for what he wanted.

“It will take a while to get your landings back. That’s all. You’ve lost your centre of gravity. Now go and change. I’ll wait.”

I couldn’t imagine what he would wait for. My blank stare? My vapid smile? My rotten jumps? These two days had presented the opportunity of a lifetime. He could have been working with the principals.

I washed layers of sweat, savoured the coolness of the water. I had a few hours to recover before our warm-up and performance. And I was keeping Daniel Tremaine waiting.

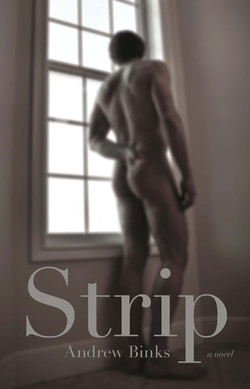

I stepped out of the shower, a little less defeated, taking a solitary moment to survey my naked form in the mirror—something less likely to be criticized. There, in the mirror’s reflection, stood Daniel Tremaine. From his mouth tumbled the words, “Would you like to go for a coffee?” Dancer’s language for everything from a mini-debrief to mini-therapy to gossip to foreplay. “Tomorrow?”

Wasn’t there a chorus line of principals cuing up for him? All I had to offer was me, second soloist. Every guy, even the straight ones, and all the women in the studio followed my eye line the next morning. It was impossible and against the laws of the universe: Daniel and John. They must have laughed, but I was grinning behind that blank stare. Romeo and Juliet were nothing compared to this.

But, whatever else he may have been, Daniel Tremaine was a perfectionist, and did give two shits about my technique. I still believe that. No man had ever been as direct. When we went for that coffee on rue Saint-Denis (there are some perks to being a professional dancer: you have time off at odd hours of the day; you feel physical one hundred percent of the time; you can sit in a Montreal café with the famous Daniel Tremaine while the world buzzes around you; and you can dream), he told me more, in his killer kind of way. “If you want any kind of life as a dancer you must pay attention. You started late?”

“I swam competitively until about five years ago.”

“So you’re twenty?”

“No. I’m going on twenty-two. Swimming was boring.”

“The dancer’s friend.”

“That’s true.” It had made me supple and strong, but I needed more than endless hours of lengths at 5:30 a.m., five mornings a week, and in Edmonton winters. “But when I started dancing…”

“It’s no use starting late only to finish early. So they’ve given you a job after five years of this.”

“A bit longer, I danced and swam…”

“Why second soloist?”

“I was next in line.”

“You should be further along. You get paid a little more than corps. So what? If you stay on this path you’ll be in a wheelchair by the time you are thirty, teaching little girls to point their toes for the rest of your life. You obviously have a gift. Don’t abuse it.” These were the first positive words I’d heard him say. “And don’t be arrogant. They always need males, especially in the Company. The prairies are a wasteland. Males don’t last there.”

“They’re born there.”

“The prairies are too limiting, too Russian. Maybe Vaganova will make you strong, but your muscles will bulge and your joints will turn to putty.”

I bit my lip, while he sneered. “You’ll be bulky with t’ighs like the Winnipeg football team. What do you call them?”

“The Blue Bombers.”

“The Blue Bombers—there’ll be no difference, in their white tights and dance belts.”

“Jockstraps.”

The right corner of his mouth reached the far corner of his eye, as he stifled a laugh. “You must know tu es adorable.” He flicked at a bag of sugar, “But your knees, mon ami, won’t last.”

“You’re telling me to give up on second soloist?”

“The Company repertoire is tired and boring. Romeo and Juliet is their newest ballet in what, thirty years?

“The Company’s expanding.”

“Not if they want to tour.”

He was right; Romeo and Juliet had been a gamble that paid off. And as far as my knees were concerned, he was right; they burned every time I stepped up onto the street curb, although they were fine in the studio. The hours I had spent dancing now rivalled all of my schooling, ever. As a child I badly wanted to get up on that stage with Nureyev and Fonteyn, even if I was going to be stuck beside the scenery or in the shadows, holding Rudi’s cloak. No matter if it was The Nutcracker, Rodeo or Swan Lake that my mother took me to, sitting in the audience while the action was onstage was pointless.

Seven years ago I stopped twirling around the basement, slipping on the carpet, wearing holes in my socks. I stopped dreaming. In fact, it was a Thursday in early December that I took the leap and lied about a trip to the doctor for a flu shot. Yes, I climbed that same narrow staircase that led to our family doctor, but kept right on going. Up. Up to the place that made the high ceiling in the doctor’s office throb and sent fine plaster dust snowing down during checkups. Six months earlier, on the staircase where I had previously seen only armies of young girls with tight buns on their heads, I saw two male dancers ascend. If there were other men dancing in Edmonton, I would, too, but it took six more months of dreaming, yearning, gathering my gumption.

Soon I lied about other things—swim practice, movies, getting together with friends. All traded for a dream. (Look at me now, lying about everything, to everyone, myself included—sitting in this stairwell, now, has nothing to do with the dream.) Up I went, like Alice following the rabbit down the hole, but in the other direction, to a wonderland of Chopin played on out-of-tune pianos, the thick scent of old lady perfume, sweat, talcum powder. Bodies wafted corner to corner across creaky floors, mirrors for walls, boxes of resin in room corners, people dashing from dressing rooms to studios, draped on the barre, sitting splayed in hallways, stretching, waiting for their class to begin. In the musty windowed office Lisa, my first teacher, looked over the class list. “Are you a football player?”

“I swim.”

“We get football players. Their coach sends them. A few times and then they’re gone. It can’t be the tights, can it?” She smiled at me. I relaxed. “God, football. Football is some kind of abomination to human movement. It frightens me to see these guys with clunky feet and mitts for hands—banging their knees sideways. Funny, in the long run, ballet is probably going to do as much damage.” She winked at me.

“I want to dance.”

“Show up regularly and I won’t charge you.”

After the class, she stopped me at the door. “Will we see you again?” She smiled. My father could have adjusted her slightly protruding eye teeth. I could tell by her openness that she liked men, a lot. She said a lot of guys who started late had careers. I couldn’t believe we were talking about free classes, talking about careers, like it was a possibility and not just a dream. My whole world was starting to shift. I was involved in something I absolutely loved.

“Keep swimming,” Lisa said, “for now.”

So there I was plié, tendu with the beginner adults, women and the two men I had seen on the stairs. Then Lisa threw me into a room of little girls balancing on tippytoes, learning the syllabus, for a moment, and after that into seasoned recreational adults with timid wrists and tight fingers, until she figured I could rub shoulders with those who had hoped to be dancers one day, and along with them classes of serious teens with talent, strength, discipline and their dreams still in front of them. This all meant that some nights I was at the studio for up to four hours. The girls needed a male partner for their exams, and the adults wanted partners to make class more challenging. And all I wanted to do was dance. A simple port de bras at the barre was enough to satisfy the craving. I couldn’t wait to get to the studio, change, stretch the soreness out of my muscles and see how much further I could turn and how much more controlled I could be when I leapt. At night I dreamt I was so much better. When I swam I reached for the end of the pool; now when I danced, I reached for the heavens.

“Just turn,” Lisa shouted, while I made myself dizzy with tour en l’air. “Worry about your technique later, just get around for God’s sake. Be careless.”

Classmates started to recognize me as a dancer. And if I recognized them on the street, they’d introduce me as “one of the dancers from the studio.” It seemed unfair that because of my sex I was fast-tracked. Being called a dancer can be like a drug. Yet I didn’t feel deserving of the title, not then.

Soon Lisa asked me to come and dance with a group of retired pros in the morning in the Company class. “Stay in the back,” she told me, “and follow. You’ll get it.” I skipped school to make that class, and soon we were rehearsing for festivals as far away as Red Deer. Fantasy ballets. Ukrainian folk dancing—holding the girls by the waist on cue—them grabbing my arm, run here, run there. Jump. Kick. Wait for the applause. Bow. I begged off my parents’ European tour (it was Mom who wanted me along, not Dad) with the excuse of a part-time job, but while they toured Europe, I toured the sun-baked stages at Alberta county fairs. Old ladies and the odd queer stage door Johnny off the farm were my fans. I looked like an honest-to-God dancer.

My body took to it. My brain. My balance. My thighs thickened, counterbalancing my aching butt. “You’ve got to stretch all the time,” Lisa said, “especially in this heat—take advantage of the heat. You need strength up the back of your legs, too.” My swimmer’s shoulders screamed with each new partner I lifted. My lower back ached. And I couldn’t keep my eyes off myself. I am still obsessed with the potential for beauty, proportion and line.

Lisa had said I wasn’t too old, and when Madame Défilé, Lisa’s wrinkled, stooping boss and mentor—and a Canadian dance icon whose old-woman perfume scent infused the place—learned I was serious, she challenged me, as if to prove Lisa wrong. “You’re the swimmer,” she said in fading Queen’s English. “Maybe we can make a dancer out of you, but I doubt it.” She would grab my leg at the top of a grand battement and push it higher, shoving her sharp nails into the back of my knee. “Don’t cheat!” She shouted her commands. With her back to me she would pull my thigh from its joint, while leaning against me to keep my hip back, in a tug-of-war with my torso. Then she’d shake my arms. “You’ve got to press the weight of the world down. They aren’t just there to hang off the side of your trunk. Now presssssssss!”

To get what she wanted, she slapped me and screamed until her pale powdered face turned pink. From time to time she would throw me out of the class and then ask me what the hell I was doing sitting in the waiting area and “Get the bloody hell back in here you bloody son of a bitch, if you want to dance then bloody dance for the love of God. Show some spine.” I suppose I was a whipping post for all the princes who had never courted her. Once and only once did she waver. We were facing the barre in arabesque and I tightened the hell out of my lower back while squeezing my butt to get my leg up, the muscles fighting each other to maintain the form, while stretching my leg through to the end of my foot. “Now John, that’s good,” she said. Did I hear that correctly? The pianist stopped playing, the other students fell silent.

“You others would do well to follow this young man’s example. He’s working bloody hard to make up for lost time and though he may not make it, I have a feeling he’ll die trying.” Her compliments were calculated and short-lived. “Swimming isn’t enough. Do weights,” she shouted. “Cans of soup if you must, lots of repetitions, until it burns. And push-ups. Drop and do forty. Now! You wait until you have a men’s class, then tell me you want to dance. Swimmer ha! Have you thought of joining the army? It would be a hell of a lot easier.” In spite of her reputation—she had garnered a Governor General’s award bringing ballet to the prairies—she was slowly forgetting and being forgotten. It was obvious she would never get the perfection she demanded from anyone. In the end, I heard, she died alone.

Maybe I can blame this all on Lisa: she said I could do it.

But Daniel didn’t have time for these trivialities. “Everyone wants a kick at the can,” he said. “You won’t be pretty forever, you know. In the meantime… you can kiss me.”

“Here?”

“You’re in Montreal now.”

“And?”

“You have a look.”

“I scraped my nose on the bottom of the pool. I was fifteen.”

He didn’t care. “No. You are more than second soloist material. Any male can become a second soloist, if he has a pulse. You have line, proportion, height. You’re already halfway there. But you could be a prince. You’ll reach your prime a little later than normal but you were born to be a prince.”

“That’s my plan.”

“Then you are going about it the wrong way. You’ll be a shabby has-been—on the prairies—and that’s all. You’ll be bored to tears. How many times can you dance Fall River Legend, or Rita Joe? It’s a small dusty repertoire of museum pieces.”

I realized he was encouraging me to leave the Company; dancers never berated Agnes de Mille, or Vaganova or Russian technique for that matter. My head spun, this time without my body attached.

“Montreal can be your threshold to the bigger world of dance: the States, Europe.” But I only wanted to go where he would be. “It’s a nice nose, by the way,” he said.

“Yours is nice, too.” Actually, his was magnificent.

“It’s one of my Mohawk parts. I’ll show you the rest later.” My heart swelled, my chest expanded, but it was my legs I had to squeeze tight. This was a head-to-toe solid dance master, a real man that, for some reason, I had all to myself.

I followed his steps closely. He took me back to his home, the kind of place where you’re never sure if you’re inside or out—loft, terrace, rooftops, skylights and trees—and that’s where he wrapped his wiry arms around me. There was a ballet barre in his huge bedroom. I saw him moulding me into the next Godunov.

“Come here.” He pulled me to his mattress on the floor.

“Baryshnikov sleeps on the floor, too, but without a mattress.”

“Baryshnikov is nothing but bullshit stories about Baryshnikov.”

Up to then, only six men had touched me, physically, in my life. And each time felt like the first, and freed me once again from all the years of indecision, confusion, questioning and holding back. It had been an adolescence marked by disappointment, pretence and fakery. The breakthrough came when the swim coach offered me his Speedo, the day I forgot mine. I knew my fate when I surreptitiously took it home to spend some alone time with it, later telling him that I rinsed it for him. Our eyes met when I handed it back to him early one morning. Then, on a subsequent out-of-town swim meet, he pretended to be tipsy (as I had done up to then, when it came to begging off kissing my latest girlfriend), but it was me who took advantage of him. Desire put me in the driver’s seat, but he knew exactly what he was doing on that motel bed.

And though Daniel was number seven, that afternoon he took the number one spot as he ran his finger down my sternum. He pressed his palm onto my chest, as if he were trying to leave an imprint on my heart, and I let him. He tickled the ridge of my lips with his fingers until they twitched in anticipation of him touching his lips to mine. He worked on my flexibility, every night for a week after that first afternoon, stroking my inner thighs—to start with. As far as I could see, having him make love to me was the only thing that would cure that blankness he said he saw. I was still technically a virgin; I wanted Daniel to change that.

Sure I’ve had moments where I thought I could see what was going to save me, change me, open me up, turn me into a great dancer. I never believed it had anything to do with love. Every new teacher I encountered held new hope, and many of them fulfilled that hope, with a gem of their knowledge. I owed my grand jeté to these gems (think of jumping after you’ve left the ground; if that doesn’t work think of a hot poker up your ass). Then, with another, my body changed its interpretation of a tour en l’air (think of one side of your body trying to catch up with the other, think of the stability of a brick shit-house). But after all is said and done, it’s love that fills in all the empty spaces and makes you dance better, love that transcends the physical plane, love that couples the true material with the ethereal, joins the dance with desire. I became weightless for that week, and for weeks following the Company’s departure. All I could think was, This is my moment at last, and God, I am so ready for it—from now on, things will be perfect. But it was lust, that’s all. And I’m starting to think that the uplifting effects of lust, like caffeine, alcohol or cigarettes, eventually wear off and leave us feeling and looking like shit.

My Winnipeg roommates—hunky Peter, a solid and story-book-prince stunning Ukrainian, and the chain-smoking Rachelle (who was our landlady, also happened to be our roommate while on tour, and also happened to be a co-corps de ballet member, pas de deux partner and confidante)—both forced me to come clean in an empty coffee shop, one rainy morning on Rue Crescent. We sat in idle chat, commenting on stylish or down-and-out passers-by, dreading the matinee, until Rachelle spoke. “So? Come on. You’ve made up your mind haven’t you? Is it love? Are you moving in with him?”

“It’s time to move on,” I said. “I can’t get comfortable with the Company. I’ll end up rotting on the prairie.” I actually had myself convinced. Looking back I can see how easily I can make myself believe anything.

“Rotting on the prairie? Mr. Rottam is rotting? They’re planning The Rite of Spring and The Firebird and you say rotting, Rottam?”

“They’ve been planning those for years. It’s some kind of publicity stunt. Do you actually think they’ll get around to it before we retire?”

“Kharkov has started running ideas for Serenade.”

“More Tchaikovsky?” I teased Rachelle. She loved Tchaikovsky; so did I, but he became our whipping board for everything from music to sexuality. “Feh! If he were alive, he’d be writing movie music.”

“So John Williams is a slouch? What the hell’s wrong with movie music?”

But my leaving was a betrayal. Peter was mum, resting his chin on his hands like a scolded puppy, and most likely worrying about being an understudy that afternoon for an injured Paris. He’d rehearsed it to death and the dancing wasn’t really that difficult. He just had to look good, which would be no problem. He finally spoke. “So, it’s about dance? Or him?”

“I don’t know. My mind is too crowded. There’s him…”

“And all the thousand and one nights you’ve yet to spend with him.” Rachelle said.

“And the possibility that I could be better than a soloist, with some good coaching. He really believes…”

“But do you? Come on, dig deep.”

“You’ve seen me dancing these past few days.”

“Yes, we all have.” She droned, “Big deal.”

“Big deal? I can do it. I am so centred right now. I turn on a dime, and just keep turning. Did you see me today? I turned five times…”

“I’ve turned seven, and on my dick, and with my eyes closed.”

“Correction, Peter. You were on someone’s dick.”

“Hey. No potty mouth around me—you cocksuckers.”

“…and then I just stood there on demi-pointe in a perfect retiré with everything so aligned. If it hadn’t been for having to have coffee with you two I could still be there. And my grand jeté is…”

“Yeah, we know, grand. We saw it. Come on. Cut this shit,” she said, holding in a drag. “You’re in love with that frog. Am I going to have to clean out your room back home? That’s all I want to know.” She paused for a moment savouring the smoke. “God, I love how everyone smokes here.”

Rachelle had never babied me, not from the moment she parked herself outside our upstairs bathroom with a can of cleanser in one hand and a sponge in the other, telling me it was my turn to clean up the pubes in the bathtub. Peter could be as harsh, too, but he knew when to stop. He never let on if he had actually had sex with a man but he had become a friend after some fumbled attempts for us to be bed buddies. Not a good idea for roommates—we ended up just cuddling.

There is something like a double negative about doing it with someone you know, as a friend, who also happens to be a dancer; it takes an awful lot to become aroused, simply because you know all the ins and outs of their physique, mostly their flaws, and it is almost clinical as to how you know them. But he was definitely the hottest dancer I had seen that side of the Ontario–Manitoba border. As well as cuddling, we spent time physically close to each other, massaging shoulders, feet, ankles while watching whatever Rachelle and her husband wanted, usually Wheel of Fortune. Making it even less of an issue, we both talked about his body like it was a commodity we could both appreciate from the outside. We’d agreed that it was my weaknesses—low arch, tight tendons, feet that wouldn’t stretch—that would make me a strong dancer. And it was his gifts—perfect feet, high arches, a beautiful line, flexibility for days and visible muscle beneath his paper-thin olive skin—that would get him to where he wanted to go.

But perfect feet and flexibility can be a curse; they can hinder your strength. He was the first one who enlightened me on that, after a particularly shitty day in the studio. I decided to walk home in the rain in order to catch terminal pneumonia, if possible, and he got off the passing bus to accompany me. With his great instinct for knowing when I needed a pick-me-up, he punched me in the shoulder and said, “It is your weaknesses that will make you a strong dancer.” I’ve repeated it to myself a million times since. It became my mantra in class with every tendu, developpé, and every session with my feet locked under the nearest radiator to stretch my tendons. And the mantra worked. So there was something more lasting to our relationship than the physical. During rehearsals and before class we stretched each other incessantly to the point where we must have looked way too comfortable physically, like twin sisters, Siamese twins. And if that were the case then Rachelle was our den mother. Even so, Peter wasn’t above being a bitch, especially now that I was smitten. “It sounds like this is your big chance.”

“Let me ask one minor question here: has he even asked you to make the move?” Rachelle asked.

“Thank you, Ma’am!” Peter said. “You took the words out of my mouth.”

“Do I detect a note of sarcasm, or is it jealousy?” Peter and I were drifting. I hadn’t felt the same bond recently. Maybe we had had too many weeks on the road. He was odd, distant. Was I a threat? How could I be a threat? True, I had been promoted to second soloist just months before this tour, and he had stayed in the corps and we had it out over that—tears, the jealousy thing (although I had hoped he’d be a little more jealous for my own ego’s sake). After sharing a litre of Mogen David in some snowbound stop on the northern Ontario leg of our tour, where we performed in a cold gymnasium and slept in bunk beds, we breathed heavily from our respective bunks and stared up into the darkness. He actually found the nerve to speak, however drunk: “It’s politics; Kharkov has to show the board he doesn’t play favourites.”

“So Kharkov hates me? Is that what you’re saying? And he luuuuuuvs you?”

“No love lost, let me put it that way.”

Later, sober, I was more willing to consider it. But now, here in Montreal I, along with the whole company, was sure Peter was next on Kharkov’s list of conquests. Kharkov promoted me because he had to; he would promote Peter because he wanted to. Peter was a shoo-in for a long career.

“No, he hasn’t asked me. Not yet. It’s strange, but I feel like meeting Daniel is my chance to really find myself, as a dancer.” I actually believed this, then. Now, I’m not so sure I like what I’ve found.

It was Rachelle who persevered, “That’s bs. It’s the same bs I told myself when I married Gordon. Now look at me.”

“You thought Gordon could teach you to dance? He’s a… what the hell is he anyway?”

Gordon referred to himself as an engineer, but he was unlicensed jack-of-all-trades from plumbing to wiring. He’d wear his dirt-caked boots around the house. Rachelle would scream at him. He’d call us fairies. They’d slam the bedroom door and go at it—sexually—and Peter and I would turn up Jeopardy on the tv. It was almost like having a family.

“I meant being in love. Married. He would be my escape hatch.”

“Wasn’t he?”

Rachelle inhaled nicotine with every breath throughout her day when not dancing. She was sallow, her ridged teeth were tobacco stained, but every night, minutes before curtain in tights and tutu and tiara, she looked like the world’s loveliest princess. She had the perfect Company body; Kharkov loved tits and hated thighs. It was a tough type to find, but any female with an ounce of meat on her thighs didn’t stand a chance. Every company had its type.

“It’s a pretty good sex life when you get home from tour, from what I hear on my side of the hall.”

“If the sex weren’t so…”

“Stellar?”

“It can help you ignore other things,” she said. “That is something you should experience: Kharkov can be breathing down my neck all week, trying to crush me for the millionth time, and I think, Who cares? I’m going home to get fucked, wildly, unapologetically and furiously. And I know it pisses Kharkov off—royally.”

“I hate you.”

“Everyone needs an outlet. Looks like yours is going to be in Montreal. Anyway it’s not always perfect. What do you think hubby’s been doing for the past seven weeks while we’ve been taking Barnum and Bailey’s across the country?”

“Framing houses?”

“I don’t care what the fuck you say—men, gay, straight, when it comes to love they’re all assholes. With the exception of you two, my dear hearts.”

“Who said anything about love?”

“Just make sure you have a plan—a Plan B.”

“Plan bs. I need retraining according to him.”

“Him? I’m sure you’ve discovered something more apropos to call him.”

“Monsieur Tremaine.”

“Oh, s’il vous plait.”

“Okay, Daniel.”

“Daniel. My sweetie. Mon amour.” She smooched into the air.

“Great lips for a blow job. No wonder hubby sticks around.”

“You pig. Cochon.”

“Seriously. I can feel it—in my knees especially. Can’t you? The Company forces everything—arches, knees, ankles. I’m surprised I can still walk.”

“That’s ballet, for shit’s sake! I don’t believe a word of it. You’re just repeating a bunch of stuff he’s told you.”

I looked at Peter, who just stared open-jawed. People get antsy when they see someone genuinely happy. He finally spoke. “Maybe you just don’t have a natural turnout.”

“I think we’ve been down that road of me not having natural anything at this point, o perfect one.”

“If the ballet slipper fits…”

“Of course Captain Bohunk here—and notice how I emphasize the hunk, dear—and his knees of steel from years of shumka-ing.”

“You’re just not as sturdy.”

“True.” I had to somehow prop Peter up, as if I were betraying him, which was absurd: we were all in it for ourselves and no one else. “Now if only we could get you to keep your shoulders down when you turn.”

“So all of a sudden you’ve become Monsieur Tremaine’s secretary? My shoulders are just fine without your help.”

“Maybe you should relocate your tension.”

“To my butt, like you?”

“You have such potential.”

“Maybe Daniel is making you weak at the knees.” He sounded deflated now, and distant. I would miss him, no doubt about it.

Rachelle picked up the slack. “Poor thing! You’re letting this Daniel brainwash you. When you stop hurting, your joints I mean, you’ve stopped being a dancer. When your nuts have stopped hurting, which I’m sure they haven’t since we got here, he’ll break your heart. Trust me. Peter, tell him I’m right.”

“She’ll say anything to keep you.”

“Of course I will.”

“He sounds like a trophy, that’s about it,” Peter spoke, barely moving his lips.

“You’re saying he’s too good for me?”

“Get him to un-blank that stare of yours, then we’ll talk.”

“That blank stare is called concentration. Maybe you should try it.”

“Yeah? Well you should be concentrating on your audience—or maybe you are—yourself and your big ego.”

“Hey! No nut-cracking. Grow up. Both of you!” Rachelle turned to me. “The broken heart? It will make you a great dancer.”

That night I phoned Daniel from the stage door, between acts.

He said, “Just talking to you gives me a boner.” And I danced act two with as much of an erection as a dance belt will allow.

I was hooked like Juliet, believing nothing would keep us apart. Not even the warring dance factions of the West versus the East, the Vaganovas versus the Cecchettis. It was a dream, me fleeing the Place des Arts fortress in a cab, through the lighted boulevards of Montreal. Prokofiev’s music finally making sense. The ebb and flow of the lover’s pas de deux went over and over in my head all the way to Daniel’s place, where he met me at the door. He kissed me. “How was the show?”

“Fine. Peter was Paris. They loved him. He’s on top of the world.”

“He’ll go far.”

“He might,” I said, but Daniel was already on his way up the stairs and all I could do was follow his broad smooth back, semi-naked ass in loose pyjama bottoms, and wide feet up the narrow stairs to the rooftop for Campari and soda mixed with foreplay. Why had he said that about Peter? Was I too easy? Or stupid? But Daniel’s grasp reassured me. We had a hot nightcap and our own twisted pas de deux until the sheets of his bed were wet with sour Pierre Cardin–scented sweat. In the times to follow, it started with him heavy on my chest. The pressure of his growing erection would press up between us. I can’t sit still when I think of it. (Evidently I have no trouble separating a broken heart from the sex.) Or he’d press his torso just below my rib cage, arch his back, raise his head and we’d wait and wait and drip and then he’d go tight and his thighs would tremble just before exploding—shooting up between us, onto my neck, the odd times stinging my eye. After, I wanted to own him; do something to show this was mine; write I love you with my tongue, tracing the silhouette of his back and spine, over his tailbone and into the softness of his dark barely hairy crack, down his thigh, back of the knee, vein-wrapped calf, the scar that had made him a legend, over heel to the rough part of his tarsal where the years of dancing could be counted by the shades and toughness of the skin. I wanted to devour him.

“Stay.” He had said the magic word.

“Where?” I had acted surprised.

“Here, in Montreal. The Conservatoire isn’t great, but it’s not the prairies.”

“It’s been on my mind—six weeks of forty below zero, then the tour—besides Kharkov has gone off me.”

“He’ll use you up. Now is your chance. I’ll find you work.”

Somewhere there was a Romeo waxing poetic to the sun rising in the east as I got back to the hotel. As usual, Rachelle had built a giant nest of pillows in one bed with herself, the not-quite-dead dying swan, unglamorously earplugged, eye-masked, propped sound asleep and snoring with the tv still flickering. Prince Charming, even beautiful in his sleep, was in the other bed, which we normally shared. I was exhausted, confused and getting tired of listening to myself around these two, knowing they weren’t convinced of my decision. My body ached, but I did something I hadn’t done in ages. I crawled under the covers and held Peter tight.

He whispered, “Kharkov kissed me.” Peter was awake.

“What?”

Peter turned. “He kissed me when I got back to the hotel. I was hoping for a new contract, to be honest, but he closed the door to his room and…”

“Fuck. That pig!” I surprised myself with my own feelings of jealousy. What was it I did not have? Peter always had admirers, and he never seemed moved by it.

“He was decent. Not piggish. Coy, I guess.”

“Then?”

“I left. I mean what do you talk about with a Russian masochist whose English is limited?”

“Sounds like you’re up next for soloist.” So thrived Kharkov, and his habit of making appointments with the certainty of being thanked in a big way. Two of the principals had spent several years of their prime thanking him. Kharkov would find Peter delicious.

Later that morning my resolve was even greater. It was true: Daniel was showing me the way to my dreams, and reminding me not to sit back on the comfort of a Company contract. At the same time, I had fallen for him and all that goes along with it; it joined me to humanity, the universe and everything in between. Walls fell and I discovered a hidden energy. I became a greater dancer than I had ever dreamed of—jumped higher, turned faster, balanced longer. There was a completion to my technique. I believed in myself, one hundred percent, for the first time. In laymen’s terms, if I were a secretary I’d type faster, burn through the filing system; a house painter, I’d end up with the Sistine Chapel in fifteen shades of neon; a bricklayer, I’d redo the pyramids with a smart Egyptian faux finish. It all became so easy, so effortless. My body was rubber for those weeks—pliable, solid, tensile—all with very little sleep. Supernatural. My knees? No idea. Ask any dancer who has had time to be in love. I shone in Company class, stood in the front, flew across the stage, intimidated the soloists and principals. I couldn’t get enough of dance, or love. Did Daniel feel the same? I was too busy with all this to have any idea.

At the height of it, I gave my notice and final bow to the Company’s repertoire. As Daniel said, “Why do they call it repertoire? It’s been done, over and over and over: Tybalt, Romeo, The Nutcracker prince, any prince, anything dusted off and redone, from Ashton to Balanchine.” So I stepped out of the royal storybook, to become a finer dancer. I traded that rush of a curtain call—opening my arms wide enough to embrace three or four thousand people, and then seeing, when the house lights went up, the faces whose collective breath I’d sensed throughout the performance, all of them cheering, as they stood in one motion—for a promise of even greater praise. Someday they would clap for me alone as I stepped forward out of the line. It was time to remind myself of that dream once again. So many times since then, I have forgotten the dream.

I vowed to excel and pay attention to my technique, establish a strong foundation and secure a long career, with Daniel’s help, not to mention his international connections. This was so much more than the limited choice I had become so used to. I had come so close to being satisfied as a big swan in a small lake.

I met Kharkov in a makeshift office in Place des Arts, after company class, while I was still soaked and high from whatever it was that was forcing me to go beyond my limits. Kharkov was wearing a tailored Italian suit that he’d obviously picked up in Montreal. Everyone had been shopping their heads off before going back to Canada’s breadbasket. “It’s time to move on,” I said.

Kharkov sat still, put his hand to his mouth. I could see the wheels turning. Finally he spoke. He told me I wasn’t serious. He threatened that if I paused now, all the young dancers nipping at my ankles would finally overtake me. (You don’t cross Kharkov, was a Company mantra.) “You aren’t dancing well, you know. But I liked you. I think you know that.” As with all the dancers, I hated his grip on us. In a flash he could praise you or put you down, leave you a crumpled heap of fucked-up-ness if you cared—the humiliation and manipulation, his temper, his mood swings. Ballerinas would be in tears one moment and hugging him the next. “Promise me you won’t come back. I’ve seen so many dancers go after something, fail, wind up so far away from where they first started, I’ll never understand—bank tellers, bored mothers, strippers even. And they somehow think I will take them back. This is final—enough of your stubbornness—the Company does not take lightly to this kind of thing. You are too young, too insignificant. Are you absolutely sure?” He needed to know. It always looked so much worse for Kharkov when he lost a dancer he hadn’t fired or whose dismissal hadn’t been discussed with the board. In fact he’d been known to strike deals of irreconcilable differences, so both could save face. “You have always lacked soul. There is nothing to see when I look in your eyes. I see nothing.”

“Yes sir. Thank you, sir.”

“Perhaps Monsieur Tremaine can teach you something.” He knew. “Now get out of here before I do something both of us will regret.”

I will never know what that something might have been. Would he have kissed me like he kissed Peter? I doubt it. Maybe he wanted to strangle me. That, we both would have regretted.

But I was full of the good dancing I was doing. I looked down at my thighs, my crotch, my feet, my hands hanging at my side, parts of me I only normally saw in a mirror. I was an asset—why wasn’t he begging me to stay? I hated myself for having a brief moment of self-doubt. Although I wanted to leave with as little fanfare as possible, it would have been nice to have him regret losing me.

It was time to dance and love as others had done. I needed to keep following my heart. It was there, tucked inside Daniel’s sternum. That’s where I saw my future. I saw with conviction the rejigging of my technique, establishing myself in the East, and most of all, endless love.

I met Rachelle at Dunn’s for one last cigarette and coffee. There, surrounded by busy waiters, customers lined up at the door and glass cases of cheesecakes, we tried our best not to get too sentimental. “I’ll write to you about it.”

“Just phone. How was Kharkov?”

“He squirmed. You know Kharkov.”

Rachelle mmmm’d like she didn’t believe a word. “Don’t take any shit. The dance world doesn’t like outsiders.”

“The dance world is outsiders.”

“Not to sound negative, but I hope your prince is all he’s made out to be. You deserve it.”

She had her prince, and I wanted mine. “Take care of Peter.”

“You’re leaving a trail of broken hearts.”

“Peter? I think we sorted that out long ago.”

“He’s a sensitive boy.”

“Kharkov likes sensitive.”

“Sounds like he’s up next for soloist.” Rachelle was a perceptive girl.

“Did he tell you?”

“I heard you guys. I know all, see all. I am a woman, for God’s sakes. I just… I just don’t believe it.”

“Me neither.”

“No. Honestly. This isn’t you. It’s like you’ve been brainwashed. Yes, you’re dancing better because of all the endorphins in your systems, but it’s making you crazy.”

“Cake?”

“Oh God please no. My thighs are starting to squeak; I’ll have to start greasing them.”

When we were paying, I bought a whole cheesecake for later with Daniel. “It must be love.” Rachelle jabbed me in the ribs, her momentary seal of approval.

After the show that night, I packed my things and Peter, Rachelle and I opened a much-needed bottle of champagne.

“Altogether now, you know it by heart: Give me Veuve or give me death.”

“God, how many of my paycheques have gone up in bubbles since you two moved in?”

We drank it in a kind of noisy silence: Hotels doors banged, someone knocked on our door and an elevator bell kept dinging as if to mark the very last moments we would have together. But we sat, with our backs to it, in our own silence. “I can’t talk or I’ll cry,” Rachelle said, breaking the silence.

“You’ll probably get Tybalt,” I said to Peter.

“No. Too good-looking,” said Rachelle. “He’ll get Paris and a really good role in something new.”

“Something new?”

“Mark my words.”

Soon my thoughts shifted to the future, my future. All I could think about was getting to Daniel, and sharing another celebratory bottle with him. I didn’t want to drag this out any longer. Rachelle would get weepy if she had any more to drink—there was still a stocked mini-bar after all—and Peter was probably just thinking about his next role. I’m sure I’d already departed as far as they were concerned. We kissed, hugged, I took my bags and my cheesecake and tried not to run into anyone else, as I ran to him.

When I got to Daniel’s, we celebrated the Company’s departure and my new life. In the moonlight on the bed, after Daniel separated the seeds from the stems, we smoked and then we stuffed ourselves on cake and each other. We lay on our backs looking out into the treetops and he told me about an abusive father and a doting mother as he traced his fingers through the shadows above our heads. I told him about the big empty house in Edmonton and the anticipation of siblings who never arrived—how my father’s family humiliated my mother until it was revealed it was father who was reproductively challenged. (Was I a one-shot deal? If not, who was my real father?) Father appeased his guilt, starting with her first mink coat and continuing with her very own convertible—that woman drove a shrewd bargain. As a result, my mother referred to me as her “perfect boy.” The term was loaded with, “Since I can only have one, then he is perfect; in fact he is the only perfect male in this house…”

There, in the dark, was something I had never shared with another person. We weren’t hiding in a closet or a motel room. He stayed on the bed and I moved to the floor, leaning against the bed. He touched the top of my head with his long fingers. We were two men, two complete and naked physical beings, comfortable with ourselves.

“It’s time,” he said. “I want to make love to you, properly.”

“Soon.”

“I want to.”

“Now?”

“You sound surprised.”

I hoped the marijuana might make it easier, but the pain was excruciating. I always thought it would be so natural with the right person. But I ended up with my face pressed into the pillow, biting hard into it, trying to suppress a scream.

He gave up and dropped, deadweight, onto me. I whispered to him, “Thank you for being so understanding.” Then he sighed and rolled off.

Old thoughts about my inadequacy now haunted me. My mother drove me, her perfect boy, in her new Cadillac to the doctor’s office while I sat bent over, a seven-year-old with a searing pain in my abdomen like something was stuck inside. The pain stopped my breath, a herniated something, an incomplete something else, a testicle that hadn’t dropped. It was a series of trips to the doctor and operations in hospitals.

It always started with me standing on a small box in the doctor’s examination room, my pants around my ankles while one or two doctors poked my abdomen, stared at my penis, or shoved their dry fingers behind my scrotum and up into me so hard that they raised me up off my little snow-soaked socked feet. The efforts to find the source of that pain and rip it out blinded me. They laid their big fingers on my stomach and pressed here and there on my naked body, staring at my front, touching me.

I was innocent until a fifth visit and that one doctor looked up at my face and our eyes met. He looked like one of the ballet princes, and I retracted my hips as my penis began to stir for the first time I was aware of. While I was consumed with guilt, my mother was more concerned with her lipstick and the dashing doctors. A few years later, I was back to the doctor for another hernia, or was it bedwetting? I remember my mother had her hair done for the occasion. The doctor dug around in my underwear pressing on my abdomen, intestines, stomach, balls, pulling on them as I tried not to show spontaneous arousal. The thought of his staring, and rough pokes and soft lingering fingers, while I looked at the top of his head, sent a terrible thrill through me. Years later when I would dream of the visits to the doctor I would wet the bed, but not with piss.

We lay with the streetlight and shadows playing across our skin. I vowed to give up anything for love.