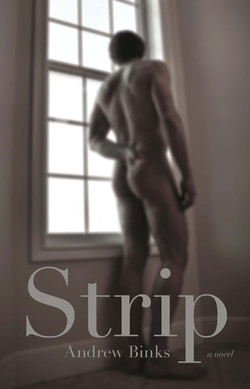

Читать книгу Strip - Andrew Binks - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTwo

A dancer’s bare feet approach the earth, toes extended. The soles, broad and thick, reach for the earth’s membrane then cushion the impact, draw history and resonance through the weathered skin from core to core. The soul is shaken free of its trance. The body again ascends—as the feet beat back at the world with entrechat and frappé—to the stars.

A door above me slams and my clothes fly down the open space at my side. I rise, look down the twenty-two-odd flights as a stray sock spirals defiantly to the bottom. Something cracks onto the floor below, cufflinks or my watch. It doesn’t matter. My belt buckle? And no one will come after me. I am in no man’s land, in the shaft of the sleek condo where I got everything I had ever asked for, or deserved, in a matter of seconds.

Sunday morning came quietly in Daniel’s tree house. We woke late, and there was no “the Company”; no daily rehearsal sheet slipped under the door; no Company class; no dour-faced dancers poking forks in lone grapes on breakfast plates and dreaming about their second cigarette of the day. Once again I was outside my safety zone. There would be no equity-minimum-for-second-soloist paycheque in two weeks. There would be no speculation on who would get what role in the coming season. Before, I had paid-for dreams and goals, but now they were replaced by free promises.

By now, the Company would be assembled in the hotel lobby for a bus to an early flight back to Winnipeg, welcoming a day off. They would later go for brunch and then put their fingers down their throats and puke, or sit in a movie theatre and worry about their 102 minutes of inactivity. Rachelle would read the Sunday New York Times Gordon had picked up earlier at the Fort Garry, spread on the floor (with the bright prairie afternoon sun filling the room, making it difficult to ignore the streaked window and the gathering dust bunnies) smoking something harsh, drinking pots of coffee, disappearing with Gordon to the bedroom at regular intervals, then making him dinner and curling up on the couch for hours of TV and wondering if the Company would make her a principal dancer someday—why hadn’t they already?

Peter would be playing with himself in his room, thinking no one could tell, or maybe he’d have his perfect feet shoved under the radiator to make them even more perfect. God bless those poor overstretched tendons. Then he’d probably get together with a few of the dancers for coffee, and not so much a chat as a series of agreeable grunts. He was social that way. They’d have Monday morning off.

I wondered if my days off with Daniel would be like Rachelle’s, until he whispered in my ear, “Come, we have a breakfast to go to.”

“So early?”

“Mon ami, it is no longer early, we have slept late and will just make it.”

When you get to know someone, you find out things about them that you overlooked—how they snore, chew, sip, wipe their nose with their knuckle, how sloppy they are or, in Daniel’s case, how meticulous: his attention to the order he dressed himself—shirt first; how many times he washed his hands—frequently; when he washed his hands—always after touching me. What did he think of me, and the way I piled my clothes on the chair, and how my bed-head looked, and how my breath smelled and how the sheets had creased my face? Did he notice?

We rushed out the door, Daniel looking far more together than I felt.

“Welcome to your first day as an independent person, not following the pack.”

“It feels strange.”

“Good I hope.”

“Good.” But I felt like the prodigal son, again.

Back at the beginning of my big dreams, I had this groovy little dance bag I’d bought at Army & Navy. After a year of dancing, disguised as swim practice, it all came out. I was between swim practice and dance class, and I had come home to wolf down my dinner. I tossed the bag by the front door and, as bags do, it fell open. Dad came home a few mouthfuls into my meatloaf. After the called Hi and the requisite, Do you want a drink? he walked into the living room with the bag, threw it on the floor, where the contents spilled—the shoes, tights, leg warmers, the layers of ripped t-shirts and sweat socks and the dance belt. “What are these?” he asked. “Something for Halloween?”

Ballet slippers. For my father, I imagine this was something that only happened to other people’s children, in other cities. This was something you only heard about and never, ever dreaded because it seemed so far-fetched.

“It’s my dance stuff.” It lay on the living room floor, deflated, dirty too.

“Dance stuff? What kind of dance stuff?”

“Shoes.” (Ballet slippers caught in my throat.) “Slippers.”

“Slippers. What the Christ?” he said. Well, wouldn’t it have been an education to see me sew the elastics on them, and carefully sew exactly where the shoe folds down? You can’t sew the elastic just anywhere, and if you want two elastics to hug the slipper to your foot, then you’ve got a little geometry to do.

“What’s this?” he asked in a confident monotone, as if the battle had been won and he was simply making a point. “A bathing suit or some queer kind of jockstrap?”

“It’s a dance belt.”

“A what?”

I wanted so badly to tell it like this: tighter than a Speedo and smaller than one. It cuts up your ass-crack. You pull it on, then grab your nuts and dick and pull up. The old ladies in the audiences watching The Nutcracker for the umpteenth time say why do they have to have those horrid bulges? It’s anatomy, honey. Arms, legs, boobs and cocks. They’ve been around for a while. So your nuts are crammed into these things because between your entrechat and anything else that slams your thighs together at the speed of light, if your nuts aren’t out of the way, you could end up seeing stars. The only hazard when the equipment is out there is turning to your Swan or Princess or Sultana and in the midst of careless fouetté or pirouette having her knee whack your nuts. The pain. The numbing, bent-over-crippling, dizzying pain. It happens to all of us at least once.

“What else? A goddamn tutu?”

“A t-shirt.” Something loose and rag-like, showing tendon. Muscle. Line. That’s the dance bag. Maybe a skanky towel for the shower. “It’s ballet dance stuff. Tights, too, for men. Black, is that okay? Male dancers wear them.”

“Part of your school work?”

“No.”

“And what about swimming?”

“I still swim.”

“In your tights?”

“In my Speedo.”

“How long has this been going on?”

“About a year.”

“Where?”

“The studio—the one near your office. Madame…”

“Défilé?”

“How do you know?”

“She’s been there for years. She came in for checkups—when she could afford it.”

He turned to my mother. “How long have you known this?” But she just took a sip of her drink and went back to the kitchen.

“She didn’t know,” I said. He’d made his point and from that moment we rarely talked. I had wronged him and his dreams and his agenda. My mother stopped talking to either of us. She’d sit in the sewing room under her poster of Nureyev and Fonteyn. I imagined her weeping though I could never be sure. I had done enough to shame them for life. There was no turning back. The distance helped me find a kind of bravado, and as a result I made another magical leap toward becoming a competent dancer. I had little—even less—to lose anymore. During his pre-dinner, post-looking-in-people’s-rotting-mouths drink, I’m sure I asked him why he was so against something so cultured, so refined, so creative. Maybe I just said, “Why do you hate that I dance?”

“I’ll tell you something about Madame Défilé. She stopped coming to see me because she owed me so much. I gave up trying to get even a nickel out of her. Do you want to end up like that? Teaching little girls to point their toes. Worrying about when the power will be cut?”

“She danced with Les Ballets Russes.”

“And she’s going to die a poor, old lady.”

“But I’m good. I really am.”

“You don’t have the talent. After one year, at your age?”

“I do.”

“Fine. Do what you like, take up knitting for God’s sake, as long as it doesn’t interfere with school.”

It was long overdue, this parting of ways, and after that I wondered if part of Madame Défilé’s fiery temper tantrums toward me were for my father.

Daniel’s words broke my reverie. “You will make your parents proud someday, and put that Company to shame. Believe me.”

And the streets in Montreal were different now that I was free.

We went north along rue Berri, past rows of old walk-ups, and stopped in front of an iron staircase leading up to a massive flat. The stranger who answered the door raised his eyebrows to Daniel. Daniel touched the middle of my back and gently pressed me through the doorway. Six men sat on low plush couches and rat-a-tatted Québécois. One of them, who had the look of Hitler youth—good-looking but evil at the same time with a protruding brow and chin, and wavy, very bottle-blond hair—massaged my scalp and told me I was too tense. This was typical; I seemed to attract these kinds of comments. And the massage didn’t surprise me as I am sure he had hoped it would, because Kharkov had reminded me more than once that as long as I remained an uptight Anglo-Saxon, I would be stuck in the corps, then after I became second soloist, it was forever second soloist, never principal as long as, and on and on…

The others ignored me.

We sat around a low table and alternated drinking mimosas with dark coffee and nibbling daintily on lox, cream cheese and bagels, which was heaven and hell for me: it was my day off and I needed to eat, but with reckless guilt-free abandon, not restrained bites. Sunday was time-out from diet, discipline and dance. For two hours, I nodded politely at their babble, but knew my cursed blank stare was most likely working against me. I understood them perfectly when they said I didn’t understand French, which happened before and after pauses, but then their chattering would start up again. I so wanted to tell them I understood French quite well, but not Québécois.

None of them cared about the Company, or me, or dance at all for that matter. Not one of them had seen the show. In retrospect, Daniel must have had some disdain in socializing with dancers. Justifiably so—dancers could be crushingly boring to outsiders, never to themselves: when you are taught that what you do is the most important, difficult and disciplined work a human could ever do, what else can there possibly be to talk about? As for these guys, they were probably trading decorating tips, or who had winked at them in the past two days. I’ll never know.

It was Sunday, our first whole day together. One of the men, Hugues, the Aryan who massaged my head, walked us to his place in the Old Port. I couldn’t help dwelling on the idea that Hugues and Daniel had known each other much better than they let on. I was feeling more and more like the soft touch in this pas de trois. Regardless, he had the decency to point out places of interest, mostly historic buildings that housed restaurants where, he said, I might be able to get a job if my French was okay. I looked to Daniel, but he soldiered on, his royal highness deep in thought until he spoke. “It will be better for you to have your own space. There are too many distractions at my place. You will be staying with Hugues. He has an extra room.”

“Of course. Perfect.” I vividly remember that snubbed feeling, but I quickly displayed my bravado. “Now I don’t have to look for a place.”

“What about a job?” Hugues asked. “You can’t work wit’ no French. And you can’t pay the rent wit’ no work.”

“I’ll be dancing, that’s my job, and mon français n’est pas parfait mais pas mal de tout, by the way.” Hugues grinned. I looked to a distracted Daniel for support, but he had that distant look I had seen in the studio. I had resources to take me to the end of the summer.

“We will still have lots of time to spend together,” Daniel assured me.

“Of course,” I replied, as if it was I who was reassuring him.

Hugues’ place was just so, all light maple and clean-cut corners that looked onto a neighbouring limestone wall in a narrow alley. At the far end of the alley, overfed tourists waddled up a cobblestone street eighteen hours a day—on the way from the metro to the crêperies of Old Montreal, and on toward the ice cream and beavertail booths of the Old Port, their floral prints and gaudy perma-press created a travelling kaleidoscopic parade of continuous colour in the distance. Fortunately the only sound that made it down the alley was the clicking of horses’ hooves from the calèche. It was all a lifetime away from my room in Rachelle’s house on the banks of the Assiniboine, in a city surrounded by infinity. I imagined Montreal throbbing with an energy of troubled cafés where lovers argued, and smoky bars where they made love in the dark corners.

Later that afternoon, leaving Hugues to his place, Daniel and I wandered silently along the Old Port to a precious gem store owned, he told me, by geologists. It was the kind of place where tiny lights in the ceiling focus on shiny chunks of polished stone, and people’s whispers were swallowed by thick grey carpet. He asked me to wait outside. I was dying to see what it was he was buying for me. It was one of the most perfect afternoons I had known.

“Do you mind if I ask how it was for you, when you stopped?”

“Considering I had no choice, a relief. It is nice to go out on a high note. Of course it has taken me years to look at it that way. But that is the reality. Look at the icons. Marilyn. Judy. Piaf.”

“You’re an icon?”

“Pas de tout, but people who never saw me dance have turned me into a legend. To be honest, I miss it desperately. Watching you do entrechat or tour jetés or anything eats me up inside. I was so much better.”

“Will I ever be great?”

“You shouldn’t have to ask such a question. Being a fine dancer is so much more than greatness will allow. To be great you need an ego, and you must be lacking a soul—like me.” He laughed at this, but we knew it had an element of truth. “It will be up to you to be fine, but not great.”

That week, we met for meals and sex and I took open class at the Conservatoire. I never stayed over at Daniel’s again; he would come over to my place and then go home. We needed the time—a courtship, I told myself—to get to know each other.

He came over late on Saturday night, a week into my new life, after attending a closed rehearsal. Daniel lay on the bed staring at the ceiling, his nose whistling, after another sweaty attempt to penetrate me, while I sat on the toilet telling myself the pain would lapse.

“One week. It’s been over one week,” he said. “You’re afraid to let go. You will never be free as an artist or a dancer if you can’t let go. You will be nothing more than an uptight Anglo from the prairies.” Then he left.

We were good with silences—connected enough to not need to speak. In spite of this little obstacle, I felt something was about to change with some kind of proposal. Then, with the little piece of polished rock he would give me, we would become the toast of the Montreal dance world. Our names, John and Daniel, would be on everyone’s lips. I would be his protegé. He would be my master.

Sitting here on the stairs, even now, body as it is, bereft of tears, blood and sweat, it seems absurd to wonder how he saw me. What is a bad decision? What’s the difference between a bad decision and adventure, or a good decision and boredom? Do all decisions make themselves? I haven’t thought of him wistfully for months, almost a year. I haven’t pined. You don’t believe that? And I can’t even remember the last time I got one hundred percent sentimental over him and had a good old-fashioned wine-soaked wallow. The cornerstone of lust holds up those castles in the sky.

It was after I bought Egyptian cotton sheets and pillowcases at Ogilvy’s, and the salesman made a fuss over the thread count, something I’d never heard of, that Daniel became scarce. He was busy coaching, and when I pressed him for a rendezvous, he stopped returning my calls.

I’m no stalker, but love does strange things. I didn’t want to sit in our café alone, wondering if he’d drop by, staring at a bunch of other sallow-faced intense couples. I didn’t want to feel like my ass (the gluteus maximus part) was turning to putty either. I picked another café nearer to the Conservatoire, where he did most of his work, and drank endless refills of café au lait en bol and ate just one more croissante au beurre and listened to ballet brats complain about their bony knees or flat arches, and wondered just how much butter it would take to turn my obliques into love handles. I didn’t want to forget what I was: a dancer, not just someone in love. It was every part of my life. It was me. I couldn’t live without it. But it seemed the magic was slowly leaving my body.

I looked for him at Eddie Toussaint, but years ago they had banned him from their studios for artistic differences. Les Ballets Jazz was on a Central American tour. I finally got up the courage to inquire to the tight-lipped receptionist at the Conservatoire. She told me he dropped by sometimes, but only to use the space. She thought maybe he’d gone to New York, on invitation or on an emergency. Was it a family emergency and he couldn’t get in touch with me before he left? Did he leave a message? Had there been some miscommunication? Was he too preoccupied to even talk to me? As Rachelle said, “If you believe that, you’ll buy this watch.”

When I asked Hugues, again, if there had been a message, he said the same thing, “Pas de message,” imitating my harsh English accent. He was as helpful as his face was angelic. I knew he knew something, but he probably figured this maudit anglais didn’t deserve a decent answer. He seemed permanently secretive. He said there was no word, not even from a friend who fed Daniel’s cat. He had a cat?

“I talked to someone who talked to someone else who said d’ey saw him, said d’ey t’ought ’e was back,” Hugues finally said.

“He’s back?”

“Didn’t you know he might have a job as a répétiteur in New York?” Hugues grinned. “You know him. ’e ’as lots of friends, you ’ave to share ’im, and you ’ave to enjoy him when ’e is around.” After that, Hugues didn’t speak English so well.

Add to this foundering romance the fact that there seemed no plan of attack for my physique, and I lost my footing. I had avoided the Conservatoire long enough. I started taking drop-in classes, hoping it would eventually lead me to him and be noticed at the same time. I could wait no longer for some kind of dream of a mentorship with Daniel. I couldn’t dance in a bubble. I finally decided to audition for the Conservatoire, but no one took much notice, and one of their uptight répétiteurs had the gall to suggest I take a simpler class. I had gone from professional soloist, well second soloist, in the West to corps in the East. Dancers return to the basics occasionally, it does us good, so I took my training in hand and surrounded myself with summer students following a pounding drill by a Chanel No. 5–marinated, Gestapo torturess. The Conservatoire studios were legendary, but paid the price for their nastiness. Although their teachers had produced fine dancers, the best had gone off to New York and companies in Europe.

“Your technique has been forced,” the torturess said. “You will ’ave to start over. You will ’ave to relearn.”

Then another frustrated emaciated has-been picked up where the torturess left off, in a men’s class. Between pliés we did the usual sets of push-ups, with her on our back, chin-ups with her pulling down on our ankles, and pliés with each of us sitting on a partner’s shoulders, to make us solid. “Your plié is completely wrong.” She pinched my lower back with her claws. I can still feel it.

The third blow came from a faded legend. Not a Daniel, but someone who owed his reputation to all of the years that had passed. The other dancers called him the “Sugar Plum Fairy” under their breath. He was an overgrown, over-the-hill, alcoholic boy whose shape changed between each binge and purge of booze and pizza, gravy-soaked frites and Frusen Glädjé, hold the waffle cone. He whined, “You just aren’t serious enough.”

I’d heard about his definition of serious: he went down on his knees to keep his job. But all he did was pray and cry and beg. I refused to beg, but returning to the basics for a while wouldn’t hurt my technique. I had to trust what Daniel had said. So I ate less, drank more coffee, warmed up earlier, stayed later, took every class on the schedule. And I made sure to keep my appointment with Madame Ranoff, the artistic director, to make it clear what my plans were.

Madame’s office was dark. The collected years of history crowded the atmosphere, robbed the air of oxygen, turned living beings to chalk. Madame looked as transparent as the ghosts in the photographs on her wall. Her old skin was waxworks smooth, her smile small, tight and forced. Every time she opened her mouth her dentures clicked. She had been making tough, do-or-die decisions for years to keep her dancers working. She was another who had danced with the Original Ballet Russes. And like the truly intimidating legends—Graham and Makarova—she had a rock-hard soul. Single-mindedness, time and obsession turned people like Madame Ranoff and the Sugar Plum Fairy into legends.

I didn’t tell her I had cut my ties, or about my training in the West. I was a fool to think I could marry into the Montreal dance world. She must have known. They all must have thought I was an opportunist. When a dancer leaves a company, the news spreads like syphilis. And when a dancer takes up with the likes of a Daniel Tremaine there will be a price to pay. Besides, it had always been the West against the East. The West was viewed with disdain and mild curiosity, as was the East by the West, perhaps with a little more envy. “You must start over,” she told me. “How long have you been dancing?” I thought she was being sarcastic or exaggerating but she meant every word as blankly and blandly as her lifeless face muttered it.

“Almost six years, and I used to swim…” My voice trailed off. She couldn’t care less.

“You should be better than this,” she said through a burgeoning fake smile.

“But Madame, I was soloist, second soloist, with the Company.”

“The Company,” she sighed. “They have a unique way of doing things. Not that I disagree, but they have their own set of laws.” She precisely applied condescending laughter to underscore her comment: “You must forget what you learned.”

I was a specimen: the boy from the West who now had no technique, from the Company that had no standards. This boosted the Conservatoire’s collective ego. “I would like to audition for the Conservatoire.”

“In due course.”

Of course I hadn’t kissed one ass since taking class. And as far as they were concerned I was no more than some star’s arrogant bumboy. Tarnished goods. I had one disconnected connection. I had simply traded one set of lies for another. There were too many dancers in this city and not enough jobs.

Forget my knees or forced turnout, my heart had become the pulled muscle. I could point to the pain the way I could point to tendonitis or a strained groin. How could a few weeks of simple self-indulgent wallowing for a questionable love-of-my-life do so much physical damage, when it had taken me almost eight years to become a dancer? Something left my body as quickly as it had appeared. My spirit perhaps. I was lead. I had lost my centre of gravity. My limbs pulled me off my axis and had become my enemies. I was shocked at myself, and my clumsy appendages.

Booze helped. I drank in my room, and cried like Cleopatra into my Egyptian cotton pillowcases so Hugues wouldn’t hear. I went out, too. I had never been to a bona fide gay club or bar. It just wasn’t part of the discipline. There had been the odd outing with the corps to a questionable place called Tiffany’s in downtown Winnipeg but then only for a birthday. No one tried to burn up the disco floor with so much classical technique running through their veins, and so many critical eyes watching. Besides, you needed to be at least tipsy to do so, and booze had calories. (I’ll say it again, we are a boring lot.) It had always been bed by ten except on performance nights.

I unpacked a t-shirt, and the cowboy jeans for house parties. I must have been determined to re-fire the engine, get the drive back, find someone, find Daniel (I felt like he was always just around the next corner), who could make me whole again. I left home at eleven that night, after three hours sleep. I found the club off an alley of another alley. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing there. Escaping the noise in my head and the heaviness in my heart? And every time someone started up a conversation I must have been pigeon-holed as that tight-assed Anglophone, or some American tourist looking for a real Frenchman. I couldn’t hear French or English. I was caught in a twilight zone of smoking men who weren’t interested in me, and whom I found unappealing. I skulked in the dark corners with my rum and Coke and dreamed of what I’d do with some guy dressed like a lumberjack, with hairy forearms the size of my thighs.

No one had ever appreciated me the way Daniel had, and no one then in that bar seemed to find me attractive at all. I seemed to be disintegrating, like the elastic in over-washed tights. I kept my eyes peeled for his dark profile to appear somewhere in the crowd. It was only him who had made me feel desirable—lips, nose and all. How could I have felt so good? The more of my body he appreciated, the more of me there seemed to exist. As if my physical self was gradually coming into being for the first time. I’d only ever known myself from the inside out and he made me aware of the weight of me—my mass and the space I was taking up on the planet, and in his eyes. But love and Daniel were nowhere to be found.

There goes my nose. Now I am bleeding from both ends. If someone comes into the stairwell I’ll tell them I’m rehearsing a scene from Julius Caesar. Why Daniel? Why thoughts like this now? Am I not pummelled enough? My mind is searching independently for a resolution and it wants to start there, back in Montreal. I assure you I am not expecting that handsome prince at the end of this bloodletting. I would rather die.

In truth “he” was a kind of demented self-flattery for me, as in, How could someone so masculine and so commanding and so dashing, love someone so much less so (as I perceived myself to be)? That was it—Hey, everybody, look who loves me. I must be worthy.

It was the kind of thought that kept me from doing a complete dying swan. I remember Kent once said maybe I really had been in love. He said that maybe I was being too hard on love and on myself. He said I should give love more of a chance. Give myself more of a chance at being human and knowing what it is love can do. But it’s still too soon to think about Kent; we’ve only just hit the concrete, and I’m still whimpering about Daniel. Kent, in his quiet, wise way, knew more about love than I ever will. He may have been right, but maybe I knew more about lust. For the truly hard-hearted, lust can paradoxically be safer; if beauty can be skin deep then lust can be a little deeper. But in those months, I found something that had only ever existed onstage—my ego.

Since men didn’t seem to be swarming me like sylphs to a poet, my confidence dissipated proportionally. If I had pursued those strangers in the bar, they wouldn’t have liked what they found: a tired dancer with a tight ass. “What a waste,” they’d say. “You have such a nice ass.” Maybe it was evident. This was the new meaning of “rock bottom.”

Pride kept me from admitting that all Daniel wanted was my supple ass, and who knows for how long? Our survival instinct keeps us from such thoughts. In my room I drank my savings while I stared at that limestone wall. Lost sleep. Daniel had told me once in the early stages that I was sentimental “in a good way,” spiritual too, and sensitive—meaning he believed he could pass judgement, meaning he was full of it, meaning I let him do so, meaning I was blinder than Alicia Alonso. Now I even recall on our last night in Hugues’ living room, draped over the sedan, he had told Hugues he didn’t really know where we were going. I pretended not to understand as I freely and stupidly blurted I was in love, in my Le Spectre de la Rose–tinted glasses.

After diluting my pride with a gut-bloating six-pack and a few glasses of red wine, I made the call to Kharkov. Who knows? Maybe he’d think I could lure Daniel back to Winnipeg, and then he’d take me back no question.

Kharkov would not take my call, of course, but gave very specific instructions to his secretary Miss Friesen, a severe and uptight balletomane who got into ballet politics and mind games like a dirty shirt, and whose name provided no end of amusement for us more vengeful types. I was ready to grovel. “Can’t I please speak with him?”

“Kharkov wanted me to pass along his regrets. I don’t think it would make any difference. He has already signed on four very strong males—two from Texas and two of our apprentices. He has to start rehearsing them immediately for the coming season. I’m sorry.”

Miss Freezin’ was still so full of it. She couldn’t have been happier to take my call. Kharkov would use it as an example to the Company as he had in the past. He’d gloat, then they’d gloat, thinking they had landed in the biggest pot of ballet honey around, but it just wasn’t the truth. The truth was that they had a job.

I called Rachelle after finishing all the wine. Her voice grounded me. “Hello prodigal son. We miss you like stinkweed. You’re drunk. Are you with your hubby? Are you coming back?”

“That’s optimistic.”

“Which one?”

“All of the above, although I am quite inebriated.”

“A little game of hide and seek?”

“Good news travels fast.”

“Never mind. Your big plunge has caused a wave of self-doubt. Three have taken offers to dance in Atlanta. You probably could have gone with them or negotiated something. And the empty spaces have all been filled in. It’s all up-and-comers and new blood. Speaking of blood, Gordon and I are getting a divorce. Do you want an invitation to the un-wedding?”

“If I were married, we could have a double divorce.” It’s funny how the memory of replacing the receiver of a phone into its cradle lasts longer than the feeling left by the call. I have this long internal list of post–hang-up-the-phone feelings. Someone tells you they are sick, someone accepts an offer, someone says goodbye, maybe for the very last time. That moment after stamps itself forever onto your consciousness. It could be filled with silence, or a clock ticking in an empty room, or the swirl of life still continuing around you in a train station or an airport. The echoed ring from the receiver being slammed down. In this instance it was the sight of gob and tears that dripped from my face onto the floor, as I had a drunken weep. I was still on the same patch of floor the next morning, shivering, when Hugues took pity and actually brought me a café au lait and wrapped me in a comforter.

September’s cold, clear blue skies shone over everything: the city, the mountain—forcing everyone to be happy about good weather for sleeping, and a fresh start at school or work after their vacation. And me, hungover on a Monday morning with nothing to start. What now? Shop around? Find a small company? Which one? Les Ballets Jazz? Eddie Toussaint? I looked too desperate. I was dancing like a fucking broken nutcracker.

Things have been a little too stop-and-start recently for me to be a big believer in fate; doors slam in front of you or behind you. It ends up meaning the same thing. I wouldn’t have described what happened next as luck, not then. In retrospect it brought a crazy dancer, Bertrand, into my life, to save me from my ennui, unclog the cogs and get the next part of my story unstuck. But it’s not what it sounds like—not another man for my dance card. Yes, I found him attractive, but only because he was the only person I’d ever met who was as crazy and as cockeyed-optimistic—a truly nutty look in his eyes—as me.

He was passionate about dance, had a gorgeous big muscular ass and a generously loaded crotch. He was a tight package of male body odour and lean muscle ready to burst. I only mention these qualities because that is how he danced, with a suppressed energy, as if he and everything in his tights would explode in a second. His face was Depardieu before food—the meandering nose, slightly crooked teeth and wide jaw and a kind of indefinable handsome wild aura. He had studied at the Conservatoire for the summer and we exchanged glances and nods in the hall from time to time. I wondered if he was gay—he wasn’t—and he probably wondered why the hell I was staring at his crotch. We shared a pas de deux partner, which is where our paths crossed, in repertoire class.

He seemed to be the only one left to impress, so I tried to hide my increasingly shitty attitude. My dancing sucked and as a result I’d put up a barrier protected by a severe pout, the kind that says I expect more from myself and have danced much better than this, and you can go fuck yourself.

His English was minimal, and most Francophones couldn’t understand his backwoods French. We managed on a different level. I’d speak my proper French mixed with Franglais, and he would reply in his French or with halting, breathy English that made him sound like he needed oxygen. In pas de deux class he would mutter profanities under his breath. He could be so particular that you thought you’d met the most precious bitch. His criticism, if that’s what it was, forced the girls to glare and huff and fold their arms. He always snapped back at temperamental ballerinas. They already hated themselves for any extra pounds or ounces gained, especially in the summer with ice cream and slushies on every corner. They’d take it out on the men, like we were the ones who had fucked up. If one had a tantrum, Bertrand would match it and not hesitate to knock her off her pointe. I found this bravado so refreshing.

But I didn’t escape his sharp eye and tongue; one day he had a go at me. We were in the dressing room and I was towelling myself dry, wondering how I could make a quick exit without the administrator asking me to pay up. Bertrand interrupted this plan. He started scolding me while he stood naked in the shower (giving me a good solid excuse to pay attention). “Why do you bodder?” he searched for each word. “I am so sick of passionless dancers. What is it d’at you want?”

“I want to dance, to perform. I can’t be in fucking class pour le reste de ma vie.”

“Il faut choisir. There is nothing ’ere for you. You come home wit’ me tonight and we can talk.”

He was boarding at his brother’s, a beautiful space, and not something any dancer I knew could probably ever afford. Every apartment in that city was huge and unusual, whereas out west, they were standard cookie cutter. After no food and a gallon of wine from the dépanneur across the street I felt I knew him. And we didn’t sit; dancers drape or lie, or squat or scrunch cross-legged on the floor. We knead our feet, open our legs as wide as possible, to not miss a moment of stretching. I lay on my front like a frog on a specimen tray and drank wine while I worked on my turnout, letting gravity and inebriation pull my hips to the floor while my knees splayed in opposite directions.

I sensed Bertrand was a rare gentleman. I poured my heart out: “Have I made a mistake? Am I really that bad? Why won’t they take me seriously?” I cried for my dancing (but crying for Daniel was likely a large part of that). I was messy, not the tight-assed Anglophone others had accused me of being. Not tonight. If he didn’t think I was crazy then, he never would. When I was finished, it was his turn and he wouldn’t shut up. I couldn’t figure out what he was saying but it was something about a ballet company in Quebec City. He was rat-a-tatting his Lévis French. “You-stay-in-Montreal-and-train-at-da-Conservatoire-always-’oping-like-the-rest, or-come-dance-with-us-in-Quebec. The Conservatoire? Pah.”

That’s what I figured he was saying. It’s so much easier to comprehend a second language when you’re drunk. He finished up with a question, looking at me in silence until I realized he had asked me something. “Why do you do it? Why are you ’ere?” he repeated. But I was numb by then. Why did I do it? I was starting to wonder. What was I in pursuit of? Fame? The perfect fouetté? The perfect body? Attention? Love from every one? Love from just one? How long could I go on blaming everyone else? I remember once upon a time it had felt so good.

That night we slept in Bertrand’s older brother’s big bed and he talked for another hour, face to the ceiling, eyes wide, before he fizzled. His solid body crawled across me to turn off the light. I could feel his warm red-wine breath. He knocked my alcoholic erection with that fat bulge he’d kept in his dance belt. Was this a last shot at getting me to dance with this Quebec company? He may have meant well, but my instincts told me not to touch. I’d seen him briefly with a woman at the Conservatoire, and something else said to wait, just a few more seconds, for Daniel and an answer. I so wanted to hold out for true love.

I rolled away from him and stared into the dark and saw a kid, me, being shipped off on a bus for a bilingual exchange. It was une échange bilingue. French immersion. Two weeks with a French family and then a boy my age with us for two weeks. I went to a town, Bonneville, in rural Alberta. Big farms and warm wooden houses under a sky so big and clouds so high it could make you say your prayers even if you never went to church. I stayed with a French Canadian family who laughed together, took pride in everything—their food, their children—asked me lots of questions, worried over me, the English kid. They joked that I was one of them. Their son came into my room during the lightning and thunder after a prairie summer day to hold me and never say or think anything about it again. I remember the sheen of his hair. He came back, for his two weeks, to our empty bungalow in Strathcona. How different he must have found us. Our humourless hand folding and knuckle wringing, the television news at the dinner table, the stiff coughs and icy smiles. We caught each other’s eyes across that vast dinner table, but we were strangers.

Fortunately my instincts were correct. In the morning the girlfriend I had seen him with, Louise, came by for coffee before class. Sex with a man had probably never crossed Bertrand’s ballet-obsessed mind. Anyway, the fantasy of it has gotten me some alone-time mileage. And Louise was built for men more than for dance. She must have made him very happy—and he, her, if she didn’t find him too much. “You stayed over? Even I don’t get that privilege. Don’t want to dishonour the brother’s bed.” She put two pain au chocolat on the table. “Eat, eat,” she said, and we all tore bits off. “He’s told you about Madame?”

“Madame?”

“It’s her company. The one in Quebec.”

“He seems pretty excited about it.”

“Madame is a genius,” he blurted.

“What do you think of moving to Quebec City?”

“Really?”

“He won’t shut up about you.”

“But…”

“You have potential. I mean you’re being a bit sloppy right now, but we all have our phases. You were second soloist. We saw you with the Company.”

And I had seen her dance at the studio and, although she would never be part of a big company with a figure like hers (a woman’s, not a ten-year-old anorexic boy’s), she had a solid technique and strong natural instincts. For her to devote herself to this company in Quebec City, she must have been a believer.

“Wow, no one has said anything that nice since I got here. Shit, I’d be honoured.” I was intrigued by the idea of running away, but I still had to convince myself that Daniel had run absolutely cold, for peace of mind.

After our first café, Bertrand started up again. “Our company is what dance is all about—we honour the dance—we don’t let anyt’ing pass—we are not sloppy like the Conservatoire—they don’t understand how to find the dancer within a person—we are only five—with you, we will be six—you will be dancing all the time—doing what you were meant to do—the big companies they only want paper dolls who have never had a period in their lives—am I right, Louise?”

She rolled her eyes—another of her big assets—brown and dark, arched eyebrows. She was the kind of woman that made you say, If only I were straight… “You see? We do need another male.”

“We need a good male.” Bertrand slammed his hand on the table.

“’e’s jealous.”

“Of whom?”

“You’re jealous of Jean-Marc, Madame’s pet,” she shouted back at him, as if jealous of his jealousy. She turned to me. “Madame would do anything for Jean-Marc.”

Jean-Marc, the other male dancer, was their bone of contention. Bertrand obsessed about Jean-Marc. And Louise was miffed by Bertrand’s obsession.

“We need another male for our New York tour.”

“New York?” Music to my ears. Daniel would see.

Madame brought the rest of her little company to Montreal to see Le Ballet Naçional de Cuba at Place des Arts. The hall was filled with Montreal dancers from the Conservatoire, Eddie Toussaint, Les Ballets Jazz and any students who could afford it. I shared the row with Bertrand, Louise, Madame and the Quebec dancers. We waited for Alicia Alonso, the blind legend, to perform with lean, brown-skinned men who swirled around her, doubling as seeing-eye dogs. I closed my eyes, pretending to be meditating. Instead saw my young self in the audience one snowy Edmonton night.

Big old cars—Cadillacs, Impalas, Buicks—skid toward a downtown theatre. There I am, peering over the window’s ledge into a continuous stream of snowflakes flying by the car. Bored voices from the front seat drop in and out of my little window-world, blankly telling me I am on my way to see something great, that I would probably never see again.

Ballet.

It’s your father, (she calls him) who said, “I don’t know why we had to bring him along, he won’t remember.”

Your mother, (he calls her) said, “It’s easier than getting a sitter.”

Bringing me along turned unlucky for him. I could have clung to her but, no, I hung on his jacket sleeves, and the curses he muttered under his breath. The theatre was velvety and everything swirled upward. The seats were soft enough to fart silently, unlike the harsh wood pews at Bellamy Baptist. In that world of gilt and gold and plush fabric, the smells were thick, too. A woman’s powdery perfume drifted down her Dippity-do waves of hair, tumbling over the fur collar spread across the seatback, suffocating me, my throat collapsing involuntarily. And as the fur collar inched toward my little flannelled knees, I wondered if I would ever be a grown-up.

“Don’t touch,” Father scolded.

“Let him touch it, he’s not bothering anybody. Besides,” she whispered loudly, “it’s only muskrat.”

They never found out about the sticky mint I glued under that muskrat collar, in the dark, or the giant gumdrop I stuck to the back of some woman’s ermine resting on the radiator. But that was when I didn’t appreciate the price of fur.

People laugh and whisper, lips touch ears, heads tip toward me with that isn’t-he-cute nod and wink, until the sounds fade with the lights and the heavy blood red curtains obey the jab of the conductor’s baton and magically fold toward the corners of the proscenium.

And who gave a damn about the dancing back then? Anyone could do it—twirls and twiddles. I was more interested in the ballerinas looking like they had been dipped in icing sugar, and the feathers on their costumes that tickled the men’s noses and clung to their sweaty foreheads when they all danced together. I wished, in that silent world, that someone would sneeze. But real swans were much more graceful, I told mother, and they had longer necks, and didn’t clomp on tippytoe.

All those cotton candy distractions didn’t compare to my fascination with the danseurs. I could see myself as one of these princes so much more easily than I could see myself wearing a charcoal suit and tie. These men were strong like I dreamed I would be. They had poise, and shoulders and thighs that looked like they were carved from ivory. They flew, lithe and nimble, through the air. Not like us kids who dropped from trees, twisted our ankles, scraped our shins, or awkwardly leapt across prairie ditches in the spring only to fall short of the opposite bank and have our boots fill with icy water. They only bowed to queens and kings. Their legs were smooth, save for a bulge at the top.

And how could this living statue love a large white bird, when he cared more about his hunting partner? Their big legs bounced them toward each other across the stage, twirled them, too. Then they whispered, touched their hearts and softly stroked each other’s shoulders, like I had been taught not to do, one Edmonton summer afternoon on my way to the river. Benjamin Weinstein and I walked toward the water, and it was my father who shouted, “Boys don’t put their arms around each other.” So we let go and held hands. “And boys don’t hold hands.” We walked shoulder to shoulder, touching, but never again without shame. But the ballet proved me right; the prince and his buddy embraced each other in front of a whole audience, while the other handsome hunters stood like living statues—firm thighs, round butts and bulges—arms draped on one another’s shoulders, waiting for their cue to join in the dance. They didn’t mind showing their round butts, firm thighs and bulges.

“Why won’t they talk?”

“Shhh!”

But how could anyone understand the story if no one talked? Or sang?

At the intermission women tipped their glasses of rye and ginger and carefully stuck their tongues in their glasses to keep their lipstick from caking, as my mother explained.

And people kept saying new-RAYE-ev and Fon-TAIN. The men talked, laughed, whispered and belched out words into their rum and Cokes and Scotches, words like commie and ruskie, bohunk and fairy.

“What’s a commie? What’s a ruskie?” I knew how to be a shit. The women ignored me and stroked my cheeks with the backs of their hands, and I knew, even then, that if I smiled they would say something. “Lovely new teeth—fitting for a dentist’s son.”

For better or worse, with no brothers or sisters I was the centre of their attention. Everyone said how fortunate my folks were to have such a handsome—blond-haired, blue-eyed and lovely lipped—and well-behaved young man.

“Your father says you won’t remember, but I’m sure you will.”

“Your mother has a thing for ruskie fairies.” His jabs had a distinct tone; I knew what to ignore and when to pretend I didn’t understand.

No one asked if I’d ever be the next New-RAYE-ev.

At home my mother tucked me into a grown-up bed in my big room, far away from theirs. Indian rugs covered the cold oak floors. They probably still do. You’d never know it was well below zero outside the walls of that big warm bungalow in Strathcona, Edmonton.

In my bedroom in the basement, I lay in the dark and wondered what it was they liked about going out. Was it the intermission? Seeing their friends? The same reasons they went to church? Or was it a chance to drink cocktails? I figured the husbands went to make the wives happy, and the wives went to dream of princes. As I dozed, I wished I lived in that world where no one spoke and everyone was beautiful. I slept and dreamt of feathers stuck to women, and closed lips miming secrets, while dancers with rock-hard thighs flew through the sky, their tights full of sticky mints.

Intermissions, for dancers who happen to be sitting in the audience, are the side-shows of life, where egos bow and grovel to be noticed. Since they aren’t up onstage, they make sure everyone around knows they should be; the females wear their buns twice as tight, with enough makeup to ice a wedding cake, while the men wear corduroy pants just as tight, stretched over their butts, belts snug, and walk bolt upright, waddling with toes pointing in opposite directions like ducks. Then they’ll voice their opinions, refer to the stars by nickname—Misha, Rudi—and hope someone notices.

At intermission, Bertrand’s much-spoken-about Madame, Madame Talegdi, reclined on a bench in the foyer, stretching like a Siamese cat and inhaling cigarette smoke to her toes. If there was attention to be had, it would have to find its way to her, as far as she was concerned. She looked me over like she was about to eat a big steak and didn’t know where to begin. She was strong, lean and dark. With her dyed-black hair pulled tight to a knot, and her even, capped teeth, you could squint and believe she was a twenty-year-old señorita. Up close, she was an aging Hungarian woman, maybe with a dash of gypsy blood. But her presence filled the foyer. People pointed and whispered; whether they recognized her or not, she was alluring. Blowing that smoke everywhere, she made sure she was noticed. The attention was justified. When I saw her dance in Quebec City I understood. Her legs were rock hard, her ankles were a little thick from two infants and a newborn she hauled around. But she could stay on pointe forever. One afternoon the girls in her small company ran from the room, in tears, because she had shamed them by doing thirty-two fouettés without moving, not travelling so much as the diameter of a dime along the floor.

Louise and the girls sat at her feet and Bertrand and Jean-Marc, Bertrand’s nemesis, sat beside her. Louise strained to maintain a graceful seated posture, despite her full chest. If she leaned forward she was just way too luscious—a no-no for dancers though no doubt pleasing for any civilian straight males in the theatre. Other, thinner dancers in the lobby would look down on her, but she would smirk because in the end she had the best of both worlds. The Company would have called her “heavy” until she showed signs of anorexia. Someday, in the real world, her body, and all the other shapely ballerina’s bodies I had known, would be appreciated. Until then, they’d have to settle for some crazed taskmaster’s petrified idea of beauty.

Next to Louise, the other girls appeared to be corpses. Maryse, a buck-toothed and anorexic stick, ignored me outright. Bertrand admitted she could dance but then mimicked her overbite when she turned her back to him. She was all knees, elbows, shoulder blades and grey skin. She snacked on raw celery out of a baggie.

The other female, Chantal, came across as stern. She looked in my direction, but her eye-line just managed to graze the top of my head. When I phoned Rachelle to fill her in on the Company, and described Chantal—legs crossed tight, back bolt upright—Rachelle predictably said Chantal needed to be fucked. This was her solution to most women’s attitudes. Chantal had the perfect dancer’s body and profile. She stretched her feet in her shoes, and showed off her perfect arches.

Jean-Marc, the one who had brought Bertrand and Louise head to head, sat beside Madame, and presented a huge, toothy, open smile when we were introduced. Bertrand’s jealousy of Madame’s attention to Jean-Marc showed up as disdain, and Louise’s jealousy of Betrand’s jealousy registered as fury. Jean-Marc was lean and muscular with veins splitting his biceps. Madame referred to them as his telephone cords. He had a big jaw, and a perfect space between his two front teeth. He looked around the room with eyebrows raised in a Je suis innocent way. With a body like that, I’m sure he’s had no trouble making his way to the top. That didn’t occur to me those few months ago. I still believed it was about talent.

Did Madame sense I would jump her protegé in a second? It turns women on, to think their man is attractive to boys like me. It can also be a big fat insult that no one, including their boyfriend, is noticing them.

Madame finally diverted her attention from her audience in the foyer of Place des Arts. She seemed content that she had been seen by all. “Bertrand tells me you would like to contribute your talents to our little company. He says you can dance.”

Bertrand frowned, but I was growing used to having to prove myself.

“At last we can remount Rimbaud,” Louise said. “Madame has created a ballet after the French poet.”

“It’s a masterpiece,” Chantal added, toward the space above my head.

Madame pretended to have caught someone’s eye. She drew on her cigarette, waved, and shook her head at Chantal’s flattery. Like any faded ballerina, she would have killed to be back onstage at Place des Arts. You could almost taste the desire.

“We are taking Rimbaud to New York,” said Madame. “Harlem. Three nights. It needs at least six strong dancers.” Her exhaled smoke settled around our little group. “As usual Bertrand will partner Louise. He will be our Rimbaud. Jean-Marc will work with Maryse. They make an ideal match.” Jean-Marc puffed up. “I think you might be a good partner for our Chantal,” proclaimed Madame. “You would make a perfect Verlaine: jealous, in love and always in Rimbaud’s shadow.” Chantal tightened her knees, sat even straighter, and curled her lip as though the one person who could turn her into the next Alicia Alonso, and make her dreams come true with the snap of her fingers, had just cut an extremely foul fromage.

My time had finally come. This is what I had needed. Not a ballet factory like Montreal, but a small company where I had time to focus on being brilliant. Montreal was short-lived, perhaps another stepping stone along the way—the way to New York.