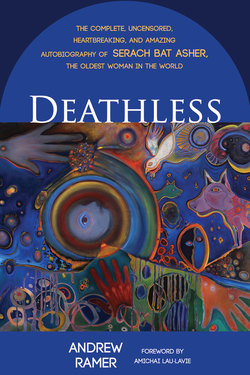

Читать книгу Deathless - Andrew Ramer - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Five

ОглавлениеHere the author finally tells you,

her dear and patient readers,

the story of her birth and

of her early years in a tent

The sky was blue, cloudless, and achingly clear. I know this because whenever we were having one of those days, Arsiyah my mother would stop and say, “Serach, this was exactly the kind of day that you were born on. Unlike your brother Imnah,” her firstborn, “who showed up right in the middle of a blizzard.” Most people don’t think of blizzards when they think about Canaan, but they do happen from time to time. We had a really big one during Roman times. Beautiful, and deadly. To this day I can close my eyes and see the desert all covered with snow, and the clouds so dense and the snow swirling about us, thick and dry. And the silence. That perfect, silencing silence.

My mother was a short round woman with a kindly smile, who was always a bit nervous, but she tried to not let that get in the way of anyone else. Her childhood was a difficult one. Her village had been burned down, its men killed, the woman and children sold into slavery. She and her mother Kalanit were freed by their owner, after many years of loyal service, and it was to my father Asher’s credit that he married her. Freed men and women didn’t have the highest status, but my grandmother Kalanit had been a priestess and her status remained with her and was part of what inspired her owner to free her. I never knew my grandmother, but my mother talked about her a lot, especially as she got older. My strongest memories of my mother are toward the end of her life, when, with her dark hair streaked with gray, pulled back from her face, she sat in the dirt, bent over a fire, cooking for us, and always singing or humming a song, in her raw, off-key, enthusiastic voice.

My mother liked to tell that story about my birth, and over the years it came to mean more and more to me, a blue thread woven through time, for a woman who never had biological children of her own. It never occurred to me to ask my mother what day of the week I was born on, as days of the week were still a new idea and we didn’t number years yet, which I already mentioned, and we honored the new moon but didn’t otherwise pay very much attention to months, although they all had names. But I liked it that I was born on a clear day. “It was the beginning of spring,” Mother added. And to this very day, when the sky is blue and cloudless and achingly clear, like glass, I think of it as my day, my own special day, a day made just for me to be born on.

Being born is really not such a special thing. Billions of people have been born on this planet. And billions of people have died here too. What’s unusual is to have been born here but not to have died. Yet. I didn’t realize at first that I wouldn’t die. In fact, for the longest time, it simply never occurred to me. I just kept getting older. So when, you’re probably wondering, did I realize that I wasn’t going to die? Well I would have to answer that question as I did before, by saying that I still expect to die, still think of myself as a mortal creature, not an angel or a vampire. Just a mortal creature who’s lived a very, very long time.

Once, in the first few years after I’d moved to California, a lively young woman named Clarice who lived next door to me in Hollywood took me to visit her good friend, a feisty and engaging older woman named Bick. Bick came from an old notable California family, the kind you read about in history books, and she lived most of the year on a large ranch in the Sierra Nevadas, breeding horses. On her land there was a sequoia tree that she said was over three thousand years old. It towered above us, straight and powerful, its branches so high up above us. “Who’d ever have thought,” I remember thinking, “that a person and a tree could be the same age?” And it was on one of those Serach Days that Clarice and I had gone to visit Bick, so the day sticks out even more in my mind.

When I was little I didn’t know that I was different. In those days we didn’t have the concept of being different yet, in quite the way that you do now. For example, I grew up knowing that I loved women, but that wasn’t considered Queer back then. It was just how some of us were. And we Hebrews didn’t even consider ourselves different then, in any way that would make us feel better or worse. We were different because we weren’t the same. That’s all. Because every tribe and group was different, and yet all of us were connected. I didn’t know I was different when first I fell in love, or when first I made love. I didn’t know I was different as I got older and one by one all of my relatives and friends died. People would often tell me that I looked young for my age, and I answered them with the ancient equivalent of “I guess I have good genes,” which was, “The goddess must think kindly of me,” by which we meant Asherah.

I didn’t think I was different when my grandparents died, or my parents and all the people of their generation died, or even when my sister and brothers started dying. But I did begin to wonder about myself when my nieces and nephews started dying. By then we’d all moved down to Egypt, and there were many distractions, so it took a while for me to sit down and soberly ask myself, “Serach, why are you still here?” and for others to begin to start asking the same question. The first thing that came to mind was of course what happened when we found out that Uncle Joseph was still alive, and what my grandfather said to me when I sang him the good news.