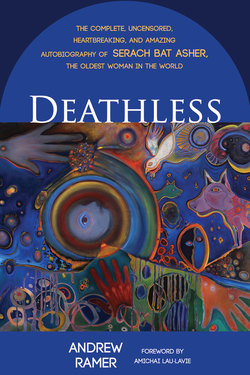

Читать книгу Deathless - Andrew Ramer - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеIn which I continue my tale and

introduce you to our earliest ancestors

I was born in a tent, and that tent seems like a good place to start my memoir, a fine place to peg my story in your minds. It was my Canaanite mother Arsiyah’s tent, and her mother Kalanit’s before her, a tent made of tan and brown speckled goat skins sewn together, section by section. Rolled up and packed on donkeys, tents like that were easily carried from place to place, from camp to camp. Now, when I look back on it, I’m amazed at the way that we lived, in such simple conditions, as we were actually a large and prosperous clan.

People think of us with tents and with camels. Some archaeologists claim that camels weren’t domesticated yet and that when they appear in early stories in the Bible they’re anachronisms, proving the text was written later. But they’re wrong. Camels were domesticated, only they were very expensive and most people didn’t have any when I was small. We had a few. Our family stock was being bred slowly, generation by generation, from camels that were part of Abraham’s father’s marriage gift to Sarah. I’ll have more to say about this in a little while.

Speaking of Sarah and Abraham, now is probably the perfect time, right at the beginning, to fill you in on who they were and on what really happened to them. And surely my ancestors (and yours) are an important part of that picture. Contemporary scholars link the Hebrew people with groups of wandering Semites called Apiru or Habiru, who are mentioned in ancient sources from Egypt to Mesopotamia. This is wrong. The Hebrew word for Hebrew, is Ivri, which means, “Those people from the other side of the river,” that river being the Euphrates, and Ivri begins, or used to, with a deep open-mouthed sound made far down in the throat, a sound you still find in Arabic, Mizrachi Hebrew, and other languages. So you can hear that the word Habiru hardly resembles the word we called ourselves back then. We Hebrews were a clan of Western Semites who roamed back and forth from Canaan to what today is western Turkey. The Habiru were someone else. Very nice people. I knew a few when I was little. But someone else, entirely.

The text that you know, the Torah, and the stories about it that our people have told over time, would have you believe that Abraham was the very first person to speak to God, and that Sarah his wife was only that, a wife and eventually, late in life, a mother. Much of this is a distortion of the real truth, but here I find myself on slippery soil, because I never knew my great-great grandparents, or my great grandparents either. What I’m about to tell you comes to me second hand, from parents and grandparents and other relatives. On the other hand, I’m a lot closer to them than you are, so you may find things here that will interest or provoke you, depending on your outlook or beliefs. This book will not be for the faint of heart or orthodox of stomach, and if you possess either, good reader, I suggest that you put down this book right now, lest it create in you mental indigestion, spiritual heartburn, or possibly both.

That little disclaimer out of the way, let’s go on. An old writing companion of mine, back in Jerusalem in the time of King Solomon, liked to remind me that the job of a good author is to establish plot, character, setting, and theme, for whoever will be reading their story. I used to be big on plot and character, but the older I get the more I favor setting and theme. So the setting for the beginning of my story is the city of Ur, the home of Abraham and Sarah. The Torah would have you believe that they came from the city of Ur that was near the mouth of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, in what today is called Iraq. Not so. The truth, and there is evidence for it in the Torah itself, is that they came from a town in the north that was also called Ur. It’s a lovely spot in what today is Turkey. I’ve been there many times. If you ever get to the Middle East, I encourage you to visit. Archaeologists say the city wasn’t inhabited during the time of our ancestors, but they’re wrong. That Ur is my and your original hometown.

Some scholars see a link between the southern city of Ur, known in the Bible as Ur of the Chaldees, and the city of Haran that is near the northern Ur. The Torah says that Abraham’s family moved to Haran from Ur. The tie between them is that both were centers of the cult of the moon god Sin. Scholars also connect the word Sinai with Sin and posit that our ancestors worshipped that god. Wrong again. This confusion is very human. Are we talking about Paris, Texas—or Paris, France? Odessa, Texas—or Odessa, Ukraine? (And why are there so many foreign places in Texas, anyway? They’ve even got a Palestine.) Back when the Torah was being put together, the real Ur was about as attractive and familiar as Paris, Texas, so the other Ur was written in, Ur of the Chaldees, a large lovely city, far more famous than the real Ur—but the wrong one.

Legends tell us that Terah, Abraham’s father, was an idol maker. This is not so. Terah’s wife isn’t named in the scriptures. She’s called Emteli or Amitlai in the Talmud, and Edna in the book of Jubilees, but her real name was Kaivah, which was a local variety of crocus, one that’s long been extinct. Kaivah was a midwife, while Terah her husband was a traveling salesman, a fairly successful one at that, who covered a territory that stretched from eastern Turkey to northern Canaan—Canaan the name that I still prefer for the land that is now called Israel and Palestine. Today a traveling salesman isn’t a job with prestige or power, but in those days a roving merchant in gold or silver or unguents, perfumes, or spices, could become a very very rich man, and Terah was quite successful in what he did.

The Torah tells us that Kaivah and Terah had three sons, Nahor, Haran, and Abraham, whose birth name was Abram. They also had a daughter named Samlah, who did midwifery, following in her mother’s footsteps, and a daughter named Istara, who did the bookkeeping for her father. Please remember that writing had already existed at that time for more than two thousand years, and all firms large and small kept records of their dealings, although to call Istara a bookkeeper when her “books” were written on clay and on dried animal skins, is clearly an anachronism, while to call her a tablet-keeper would be more accurate but an anachronism as well if you’re thinking of a computer tablet.

Reading the Torah that exists now, you find that our familiar familial story begins with Abraham and that the focus is all on him. Well, that isn’t wrong, but it isn’t exactly right either. For everything that Abraham did or said, there were just as many things that Sarah said and did. When I was little and being unruly, as all little children are (or should be, if the spark of life isn’t beaten out of them too early) my mother and my aunts would shake a finger at me and say, “Serach, remember that you’re the descendant of a princess. So start acting like one!” Mothers often say things like this to their daughters, especially if they’re tomboys like I was. But in my case, what they said was the truth. Sarah really was a princess, a minor one, but a princess none the less. Still it was hard for me to understand what that meant when I was small. After all, we were living in tents, and even then lots of little girls imagined princesses living in beautiful stone castles, or their ancient equivalents. But when I was older and had seen something of the world, I came to understand just what a princess is—a girl whose life is exalted and whose fate is restricted. You’ve seen some famous princesses in your time come and go, like Grace and Diana, so you know what I mean. Back then I was very glad that my ancestress was a princess who’d been born in a castle, but that my mother was the wife of a very very rich man who lived in a tent. A fancy tent, class-wise, but still a tent.

Torah tells us that Sarah’s birth name was Sarai, later changed to Sarah, but it was actually Innati, the name of a local goddess. Sarai or Sarah both mean princess in two different Semitic dialects, and that was her title—Sarai Innati—but for the sake of our narrative, let us continue to call her Sarah. Now Sarah was raised in a stone villa in Ur, the daughter of a rich Hebrew princess named Ataah, back in the days when women still had some power in the world. Sarah’s mother did business with Terah, Abraham’s father, who was from a less important Hebrew family. Sarah’s father, Haddad, managed his wife’s estates. Our ancestors met one afternoon when Abraham came to the villa with his father, with fabric and jewelry to sell. The two took one look at each other, Sarah and Abraham, and that was that. A flame was kindled in their eyes that raced across the gap between their bodies faster than the speed of light, something we intuitively understood, even way back then.

When Sarah and Abraham went off to Canaan they both changed their names, hers to her title in the local dialect and his from Abram to Abraham. Scholars tell us that Abram means something like, “Father is Exalted”—Father being God, and that Abraham means “Father of Many Nations,” which is more or less accurate, but they miss the meaning behind those name changes. I remember back in the late 1960’s when my young New York City neighbor Barry changed his name to River and his lovely girlfriend Mary Catherine, a self-defined “hippie-chick” changed hers to Owl. When Abram and Innati got to Canaan, they too wanted new names and new identities, and they did exactly what Barry and Mary Catherine did, after running away from their nice Jewish and Catholic families on Long Island to live in a crash pad in the Lower East Side.

All of that has been forgotten, and this has been forgotten too; had Innati been the daughter of a rich family, that spark of love which flashed between her and Abraham, who was still just called Abram, would have been snuffed out by her mother. But fortunately for her, and for all of us, Sarah was the heiress to a long vanished fortune, so Ataah was more than willing to let her daughter marry the handsome son of that very rich trader, Terah. Down through time I’ve seen this happen again and again that the children of rich, aristocratic, noble, royal, and even at times imperial lines become impoverished and are willing to ally themselves with nouveau riche clans they’d otherwise look down their noses at. You can get a handle on them by thinking of similar right-and-wrongnesses from your own time. Romans and Sicilians. South Indians and North. Ashkenazi and Sephardi. Sephardi and Mizrachi. Religious and secular. Uptown and downtown. Red and Blue, Left and Right. You know what I’m talking about.

Sarah’s mother Ataah set up the newlyweds in a large wing of her crumbling villa, but the two were never very happy there. Ataah had her own ideas for her daughter and son-in-law and they had their own ideas about how to live their lives. Ataah also had her own ideas about how her daughter’s husband ought to use his money, and immediately began to renovate the old place. In the Torah we are told that it was God who prompted Abraham to move to Canaan but in fact it was Sarah who came up with the idea. (I don’t discount the likelihood that God inspired her, although the workings of God are still unclear to me after all these years.) My mother and grandmother both told me that Sarah was a princess and a priestess and a very devout woman as well, and since the two of them never agreed on almost anything, when they did, I assume that they were telling the truth, even if it was a goddess she prayed to, the Hebrew embodiment of the Great Goddess, and not the idea of what we now call God.

Abraham was quite uncomfortable with his wealth, and was even more uncomfortable when his father died and he came into his inheritance. If they had the word then, we might say that our ancestor Abraham was something of a Socialist, happy to share his good fortune with others, who didn’t mind giving money to his mother-in-law. He only wished she’d done better things with it, like help the poor or start a school in town. Instead, she used it to fix up her villa, buy clothing, and go on fancy vacations. (Some things about human beings have changed over time; others have not.) Sarah kept grumbling about it, Abraham kept telling her that it wasn’t worth getting upset about, but our history hinges on the long forgotten afternoon when Sarah found out from a servant that her husband had just given her mother money to visit the ancient equivalent of a famous temple health spa in nearby Haran. Furious, she went storming back to their quarters and said to Abraham, the equivalent of, “I can’t take it anymore. Let’s get the hell out of here.”

Back in those days, in that area, a man moved in with his wife’s family, but times were changing and the hip, cool, with-it, trendy, avant-garde were doing things differently, so, hoping to calm his wife down, Abraham suggested to Sarah that they could move in with his father. “It’s the modern thing to do.” In those days the nuclear family didn’t exist yet and couples didn’t have houses of their own. Everyone lived in extended families of three or more generations. Well, Sarah thought about that and said, “If we go live with your dad, it’s going to be the same old story. He’s sweet, and kind, and generous, but he’ll just keep bugging us. And my mother will keep bugging us too. And you’re too nice to tell her to shut up and go away. So, darling, let’s just quit this place all together. ” Abraham realized she was right and that’s when Sarah went off to light some incense at the family shrine and pray. In the midst of her prayers the idea came to her, and she went back to tell her husband, “I think we ought to go to Canaan. The land is beautiful, the countryside is fairly open, and instead of agents going back and forth we can set up a permanent branch of your family’s business there.” Abraham thought it was a good idea, consulted with his older brother Nahor, who was in charge of the business since their father died, and Nahor agreed, so they moved, along with Abraham’s nephew Lot, the son of his late brother Haran, a kind of a hippie in his own right who was always looking for adventure.

If you’re wondering how I know about things that happened two or three generations before I was born, remember how life was in those days. No television, no movies, no books, just a lot of time to sit around and talk. Everyone loved stories, and we all told them. My grandmother Zilpah, my mother Arsiyah, and my aunt Channah were all excellent storytellers. When I was little, Grandmother, who was always sick in bed, was the living repository of our family’s history. Family members would come to her all day with local gossip and go to her for information. I took over her position when she died, and I’m still at it. I sat around listening to these stories from the time that I was old enough to sit up by myself. I heard them again and again for years and years. And once upon a time, as some storytellers say, the stories that I’m telling you were all written down. Perhaps one day some scraps of them will turn up in a cave somewhere, just like the Dead Sea Scrolls, and then you’ll see that everything I’m telling you is the truth.

Here’s another piece of history that’s been discarded. In the Torah you will read that Abraham and Sarah had one child only, a son born to them very late in life, who they named Isaac. Well it’s true that they only had one son. And it’s true that Abraham did have another son with Hagar, which isn’t a name at all. It means ‘The Stranger.’ Her real name was Isis, which was changed later on by fussy old men who didn’t want their text to include the name that she shared with Egypt’s main goddess. Funny isn’t it, sad, ironic, and maddening, that these two great matriarchs and later rivals both lost their real names.

As I said, Abraham and Sarah came from different backgrounds, and they were living in a time when the matri-focal element was shifting, rapidly. Patriarchy was the hot new thing and Abraham was influenced by it. He wanted sons, when in fact he and Sarah had three daughters in Ur before Isaac was born, Atirat, Yonah, and Kalilah. They have been left out of the story, not just because they all moved back to Ur to marry men who lived there, but because they were women and women didn’t count for much with the later editors of what became our most sacred texts. It’s true that Sarah was rather old when Isaac was born, but not as old as the story makes her out to be. A year after they settled in Canaan she gave birth to her fourth daughter, Davah, and three years after that she had her last child. We know a few things about Isaac, but nothing any longer about Davah. Although she was a powerful healer, she never married or had children, so the later editors and redactors of the Torah didn’t think that she was worth mentioning. But I do, and I’ll have more to say about her in a little while. Remind me if I forget.

According to everything I was told, Abraham was a very very handsome man and Sarah was quite a looker herself. So, while theirs was a love-match, it was different than how we think of marriage now. Well, some of you would understand it. You talk about polyamory and open marriages, and that’s what theirs was. Abraham had other lovers besides his wife, and Sarah had other lovers besides her husband. There are garbled stories in Genesis, two similar ones about her involvement with Pharaoh and Abimelech the king of Gerar, and a version of that one is also told of Isaac and Rebecca. But here’s the truth, Sarah had an Egyptian lover, name Ahmose. He wasn’t a pharaoh but a provincial ambassador stationed in Jebus, which later became Jerusalem. And later she did have a relationship with Abimelech, the king of Gerar. The storytellers got that right. But they didn’t know what to make of the story in their increasingly patriarchal society, so they bent the story, instead of discarding it, which several of them wanted to do, and then they attributed the very same story to Isaac and Rebecca, for very different reasons that relate to Isaac, which I’ll get into in a little while.

The redactors of the Torah did not know what to make of the family tale that Abraham and Sarah had the same father but different mothers. This is not true, but they did have a kind of marriage that made them the equivalent of siblings in the eyes of the law, and the later redactors took that literally. When beatniks and then hippies were popular, and experimenting with all different kinds of relationships, with free love and group sex, I couldn’t help but think of our ancestors as a kind of proto-hippie couple, devoted to each other, equally strong in their own different ways, but not constrained by their relationship in the ways that so many people are today when they get married.

Abraham was a great charmer. That’s how the family was able to settle in so easily in Canaan. He used his charm with all his family’s business connections. Sarah was also a shrewd businesswoman. My mother told me that she chose her lovers because they were good contacts for the family business, which she was also involved in. Her third lover, at least of the ones I’ve heard about, was Efron the Hittite, another non-local, a real estate investor who was a good friend of Abraham’s as well, and who sold them the cave and the land around it that became the family tomb. This tomb is not, I repeat NOT, the tomb in Hebron that two branches of Abraham’s descendants are still fighting about. The location of the real tomb has long been forgotten, and I will not tell you where to go looking for it. We’ve gotten in too much trouble already fighting about the wrong places.

By the way, Abraham’s nephew Lot, the one who came with them from Ur, did settle in the area near the Dead Sea, but he had nothing to do with Sodom, or sodomites, angelic or human. He did not sleep with his daughters, nor did his wife turn into a pillar of salt. We will see stories like this again and again, where real people like Nurit, Lot’s wife, are slandered by later writers in order to make a point. We’ll see this in the story about Shechem and Dinah and in the account of the Golden Calf, where fact is bent for political purposes. Lot’s descendants had all remained in Canaan and were hostile to the Israelites when they returned with Joshua from Egypt, and that story of sodomy and incest was those old homophobic writers’ revenge.

Now let’s talk about Abraham’s lovers. I’ll start with Hagar, who I already mentioned, and I’ll call her that rather than Isis as that’s the name you know her by. She was, I’ve been told, a very lovely woman. To begin with, she was Sarah’s best friend, not her maid as the text tells you, but she did come from Egypt. A young widow whose husband had been stationed in Canaan, she remained there after his death and she and Sarah bonded over being foreigners. As I said, the ancient world had different forms of legal couplings, as do we. There’s marriage, common-law marriage, domestic partnership, and civil unions, all of them different. We had different forms too, including marriage, sister-marriage, and concubinage. The later writers couldn’t understand that, and in your (supposedly) monogamous world (I say supposedly because you all know the truth of human nature) it may be hard to understand these different kinds of relationships.

In a world where increasingly men could have many wives but women could no longer have many husbands, and where the man’s lineage became sacred and the women’s ignored, Hagar was in a dubious position. She and Abraham were never married. They did have a son, Ishmael, who was for a time his father’s male heir. But the writers minimized her role and they diminished him too, for in their day and age Ishmael’s descendants and Isaac’s descendants had long been hostile to each other.

The story about Abraham, Sarah, and Hagar contains a good deal of truth. Abraham wanted a son, and after four daughters in a row it was Sarah who proposed that her husband and her best friend hook up. Hagar had always wanted children, but her husband had died soon after their marriage, and as women say today, “After that I just never met the right guy.” Well, from all I’ve heard, Abraham was the right guy for a lot of women, and he had a number of other children besides those mentioned in the surviving text. And while this kind of an arrangement may seem odd to you, I remember several decades ago watching a film called something like The Long Freeze, in which a group of old college friends come together for the funeral of one of their old circle. One of them is a single woman who wants to have a child, and another woman decides to lend her her own husband for the night.

Thing weren’t so different with Sarah and Hagar. But the story didn’t have a happy ending, in the text and in real life too, because thoughts and feelings aren’t always the same and a good idea in the head may be really bad news in the heart, the gut, or in the genitals. So it was with those two women who from the best of friends turned into bitter rivals. Hagar left their encampment several times, came back, but finally went off to a village where some of her family had settled, which was called Lahai-roi, from which she did not ever return. (Remember the name of this place, Lahai-roi. It will become important later in the story.)

By the way, Isaac’s real name wasn’t Isaac. That was his nickname. His real name was that of his grandfather, Terah, and in naming their son after his well-traveled father, who’d made numerous trips to Canaan, Abraham was legitimizing the family’s new location and asserting its authority. But since there already was a Terah in the story, and since no one ever called Isaac that anyway, the writers of the Torah left his true birth name out of their tale.

Here’s the missing part of the story. When little baby Terah the Second came into the world and the midwife held him up to wipe him off, he had such a funny look on his face that both Sarah and the midwife started laughing, and so right from the start his nickname became Yitzhak, which is Isaac in English, and means “He who laughs” in Hebrew. His name had nothing to do with angels or with his mother laughing at God, as the story now stands, which is a lovely story indeed.

Now Ishmael, Abraham’s son with Hagar, was no more the ancestor of all the Arabs than Isaac was the ancestor of all the Hebrews, Israelites, or Jews, those three words both synonymous—and not—but that’s a whole other story, so let me get back to this one. In addition to Hagar, who was never a full wife but a concubine, Abraham had other several lovers. Baalat the sister of his very good friend and distant cousin Melchizedek the king of Salem, Mutemwiya the Egyptian, and Tekla the Hivite come to mind. Then there was his second wife, Keturah, who he married after Hagar left and who some later rabbis mistakenly identified with her. Keturah came from a Bedouin clan that Abraham frequently traded with, and was named for their bestselling brand of incense. I’m told she was a lovely woman who put up with a lot from our ancestor, with great patience and kindness, yet sadly, our present Torah has left her as nothing but a dangling footnote. The Torah says that they had six sons, but in fact they had one son, Midian whose descendants will show up in this story later on, and two daughters, Allul who married a Canaanite man and had three daughters, and Kalyah who became a priestess of Asherah in Jericho and had no children. I knew about Allul because she was a fantastic weaver and in our tent we had one of her blankets. (What I would give for one of those beautiful goatskin blankets right now, on one of those cold damp Southern California mornings that don’t fit into the mythology of what it’s supposed to be like here.) Kalyah was a leading sculptor of her time and some of her pieces can actually be found in museums in Paris, Berlin, New York, and Jerusalem, small delicate carvings, some of them in ivory, most in clay or cast in bronze. Kalyah was still quite famous when I was a girl and all of us were proud to be related to her.

This should give you more of an idea about who Abraham and Sarah were, from the stories I heard when I was growing up in my tent of goatskins, the one that belonged to my mother and her mother before her. One more thing before I go on. After they moved to Canaan, Sarah and Abraham made several return trips to Ur to visit their families and to do business. Isaac met Rebecca on one of those trips and not the way you heard about it in the Bible. It’s a lovely story, one that I’ve always enjoyed, about the camels and the well, but it isn’t the truth. However, Rebecca’s father Bethuel was Abraham’s nephew, the son of his brother Nahor, just as the text says.

This custom of family intermarriage continued in the next generation as well. In fact, it’s still common in that part of the world. Recently, in an old file folder in my desk I came upon an article I cut out of the New York Times on May 1, 2003, which stated that up to 25 percent of all the marriages in Saudi Arabia are between close relatives, often first cousins, which was true in the past as well. This intermarriage causes many genetic problems today, and it did the same in the past. I’m thinking of my always-angry uncles Reuben and Simeon, and my cousin Initi, Uncle Gad’s daughter, who murdered her husband Baalil with a cudgel in a fit of rage. And the results might have been worse, but after Jacob and Esau’s generation, our family’s links with the north were severed, so that pattern was largely broken.