Читать книгу Textual Situations - Andrew Taylor - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Medieval Materials

In contrast to the representation of the ideal, abstract text—which is stable because it is detached from all materiality, a representation elaborated by literature itself—it is essential to remember that no text exists outside of the support that enables it to be read.

—ROGER CHARTIER

Pour engager d’autres savants à faire des recherches de ce genre, en les étendant à tous les siècles et à toutes les variétés de sujets, il convient de parler à l’esprit et aux yeux, de décrire et montrer en même temps les objets chantés et dessinés.

To incite other scholars to conduct research of this kind, reaching out to them across the centuries and in all manner of subjects, we must appeal to the spirit and to the eyes, describing and showing at the same time these sung and drawn objects.

—ADOLPHE NAPOLEON DIDRON

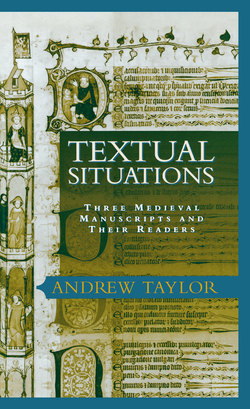

The core of this book is devoted to an examination of three medieval manuscripts, the support that enabled a variety of texts to be read and performed. One is now in the Bodleian; the other two are now in the British Library. All three have been in southern England for centuries, but apart from this proximity they have little in common. The earliest, Bodleian MS Digby 23, is a small double volume consisting of two separate booklets, each dating from the twelfth century. One booklet contains Calcidius’s translation of the Timaeus; the other the best-known version of the poem now called La Chanson de Roland. The second manuscript, British Library MS Harley 978, is a slightly thicker volume, a miscellany dating from the mid-thirteenth century that contains an amazing range of material, including the Middle English lyric “Sumer Is Icumen In,” Latin satires and drinking songs, a long celebration of Simon de Montfort’s victory over Henry III at the Battle of Lewes in 1264, and works by the twelfth-century Anglo-Norman poet Marie de France—her translation of Aesop’s fables and her short romances, or lais, which explore the themes of amour courtois. The third manuscript, British Library MS Royal 10.E.4, copied in the early fourteenth century in Italy but later acquired by St. Bartholomew’s Priory in Smithfield, on what was then the outskirts of London, is by far the largest and most ornate, a handsome folio-sized copy of the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX, also known as the Liber extra, with an astonishing series of marginal illustrations that were added later in the century in England.

Many of the works these manuscripts preserve are well known; some, such as the Song of Roland, the lais of Marie de France, or “Sumer Is Icumen In,” are famous. The three manuscripts, however, have remained all but invisible, and it is part of my purpose to inquire why this should be so. Of course, editors may always choose to ignore one manuscript witness and concentrate on another, and the vast majority of medieval manuscripts languish unread for years. But this is not the problem here. “Sumer Is Icumen In” survives only in Harley 978, which also provides the base text for almost all editions of Marie’s lais and most editions of her fables, while it is the version of the Roland in Digby 23 that has come to represent the poem. Why then has the editorial construction of the Song of Roland and the Lais of Marie de France been conducted with such comprehensive disregard for the manuscripts from which these poems were extracted? Or, to turn to the last manuscript, why do the marginal drawings from the Smithfield copy of the Decretals of Gregory IX, which crop up again and again as illustrations of medieval wayfaring life, circulate without any connection to the legal text whose borders they decorate? In examining this curious invisibility, I hope to suggest something of the way in which the material support of the medieval text, which is not just the manuscript but also the social conventions that surround it, differs from that of the printed book.

It seems oddly fitting that the second epigraph that opens this chapter should come from such a peripheral position, the final sentence of a note by the editor, Adolphe Napoléon Didron, to an article by Viollet-Leduc, père, in the second volume of the Annales archéologiques, published in 1845—scarcely the place for a manifesto. In setting out his program for iconographie studies of medieval sculpture, painting, and poetry, Didron makes three points that seem to me especially valuable. First, when he describes manuscripts as “drawn objects,” he appeals to what will become a crucial principle of textual materialism well over a century later, that texts only exist in precise physical forms, whose design, script, and accompanying apparatus are all integral parts of the texts’ meaning. This line of argument has been extensively developed in more recent years and expanded to cover modern printed editions, whose exact bibliographical format is now seen as a crucial component of a text’s meaning. But Didron suggests a second line of inquiry as well, and one that has not been so widely pursued, when he invites us to conceive of manuscripts as sung objects, stressing their acoustic as well as just their visual materiality. Finally, Didron recognizes that the study of medieval manuscripts is a cumulative and collaborative venture, one that reaches across centuries. It is a generous vision, and I can only hope that I have managed to do it justice, acknowledging my innumerable debts—to those who have maintained the tradition of painstaking scholarship that is needed to read medieval manuscripts, to those who have opened up medieval studies to the bracing winds of contemporary theoretical and cultural debate, and to those who have done a little of both.

Before proceeding any further, it will be useful to say a little more about these three manuscripts and the kinds of problems they present. All three juxtapose remarkably divergent material, and this was one of the reasons I chose them. Digby 23, as already mentioned, consists of two parts, both copied in the twelfth century. The first, Calcidius’s fourth-century translation of Plato’s Timaeus, was one of the most important philosophical texts of the high Middle Ages. The Digby version was probably copied by a Norman or northern French scribe, and it includes numerous and substantial interlinear and marginal glosses from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Later and more informal marginalia show that this copy was still in use in the fourteenth century, by which time some would have considered it something closer to a literary classic than a work of rigorous contemporary philosophy. The second part of Digby 23, the Roland, was copied either a little earlier or about the same time; most paleographers favor the second quarter of the twelfth century, although some would prefer a date as late as the 1170s. It was copied by an Anglo-Norman scribe, perhaps one working in the household of a bishop or a great magnate. There are some signs that the two parts were gathered together (that is, either bound together or kept together in the same parchment wrapper) by the thirteenth century. The first identifiable owner of Digby 23 is an Oxford scholar, Master Henry Langley, known to have been alive in 1263, who donated the book, or one part of it, to the Augustinian canons at Oseney Abbey, on the edge of town. Henry might have owned both booklets, but it seems at least as likely that the Roland was added later. However, the two booklets do seem to have been gathered together as a single person’s private collection within at most a few decades of Henry’s death, because someone has added the word “Chalcidius” to the Roland section in what appears to be a thirteenth-century hand. This would mean that the first reader of the Roland who can be even partially identified would be an anonymous canon of Oseney, possibly one of Henry’s friends. Whatever the arrangements by which the booklet came into the abbey’s possession, one thing seems clear: by the end of the thirteenth century, the Oxford Roland had become reading matter for English clerics.

This codicological information has been long known. But it has been largely, one might almost say systematically, ignored. Scholars have been remarkably slow to abandon the notion (for which there is not the slightest supporting evidence) that the Roland booklet belonged to a minstrel. Others have mounted a desperate rearguard action, assuring us that, even though the Roland booklet is found in the library of English canons, they did not actually read it and only kept it out of pious respect for their chivalric benefactors. And even now, when the idea of the minstrel manuscript has finally been laid to rest, nobody has shown more than the most passing interest in these thirteenth-century English readers. Henry Langley, it turns out, is more than just a name. There is a good deal we know about him, or at least about his father, arguably the most hated man in England in his day. But the world of thirteenth-century English clerics seems irrelevant to the prevailing understanding of what the real poem must be, an eleventh-century French sung epic. What has displaced the history of the manuscript is the modern editorial construction of La Chanson de Roland. The title of this work, which we inherit from its first editor, Francisque Michel, sums up the vision of the poem as a minstrel’s song. I have dwelt on this editorial construction at some length because it furnishes a powerful example of the way a manuscript can be effectively ignored while the words in it, or in some part of it, are treated with scrupulous care.

Each of the three manuscripts has presented different challenges, and for each I have taken a different approach. While I have grouped them in chronological order, I have also found that by good fortune they fall into a methodological order, so that the problems raised by the first are illustrated more forcefully by the second and more forcefully still by the third. In the case of Digby 23, I have from time to time indulged a certain empiricist hubris, pitting hard facts and concrete objects against the free-floating fantasies of the old philology as I call into question the very existence of the Song of Roland before its publication by Michel in 1837. My encounter with the glosses in the Timaeus, however, marks the beginning of a long erosion of that certainty, as the diversity of the manuscripts reveals the inadequacies of my knowledge. I have cast some lines from the world of Old French epic to that of the Anglo-Norman schools, but my treatment of the Timaeus remains limited and my reader must not hope for balanced coverage. If my account draws attention to some of the work that is being done in this area, work that will not be familiar to all literary scholars, it will have served its purpose.

The challenge of diversity is even greater with the second manuscript, Harley 978, a trilingual, multidisciplinary miscellany whose separate sections have almost never been considered together. Harley 978 is a small portable collection, or “manual,” to use a term current in thirteenth-century Anglo-Norman circles. Like other manuals of the period, the choice of items that were included reflects the social, intellectual, and spiritual ambitions of its owner, who would select them personally. This is a book to fashion an identity. From this single collection one reader might learn the language of amour courtois, the technicalities of hawking, various treatments for imbalances of the body’s four humors, and the arguments used against the king at the time of the Baron’s War. Harley 978 is also an important manuscript for several modern fields of study. With the exception of the lais, the fables, and a few of the Goliardic poems, most of the works in Harley 978 survive nowhere else. This is true of both “Sumer Is Icumen In,” one of the earliest and most famous of Middle English lyrics, and the Song of Lewes, the long encomium for the baronial leader Simon de Montfort, which sets out a theory on the limits of royal power, making it an important document in English constitutional history. Harley 978 is no less important for French literature. While there are numerous later copies of Marie’s lais and fables, Harley 978 is the earliest surviving manuscript of either and begins to define her canon. There are actually a number of Anglo-Norman texts attributed to a woman or women identified only as Marie and other manuscripts that contain anonymous lais in a style at least somewhat similar to those in Harley 978. The first editor, Jean-Baptiste Bonaventure de Roquefort, for example, used a thirteenth-century Picardian manuscript, BN fr. 2168, and made up a somewhat different collection.1 And only one of the Harley lais, Guigemar, actually mentions Marie by name, the eleven others being anonymous. Yet the elegant, early Harley 978 has carried the day. For modern readers, the Harley lais have taken on the stability of an authorized collection; they have become the Lais of Marie de France. Some scholars go so far as to claim the order of the lais is the very order Marie imposed in a final reworking or assembling of her work.2 Works that might be attributed to Marie but appear in other manuscripts receive far less attention.3 Despite the manuscript’s preeminence, however, there has been a staggering indifference to its full contents or to the history of its readers.

The debate on the identity of Marie de France offers a somewhat embarrassing illustration. Most scholars now accept that the author of the Lais, who at the beginning of Guigemar calls herself “Marie, ki en sun tens pas ne s’oblie” (Marie, who in her day should not be forgotten), is also the author of the translations of Aesop’s fables, who tells us in the epilogue, “Marie ai nun, si sui de France” (Marie is my name and I am from France), and is also the author of the tale of a knight’s descent into the otherworld, the Espurgatoire Seint Patriz, who tells us at the end, “Jo, Marie, ai mis en memoire/ le livre de l’Espurgatoire” (I, Marie, have recorded for memory the book of the Purgatory).4 Marie obviously must have been born in France but later lived in England for her name to make any sense. It is generally assumed that she was an aristocrat, someone elevated enough to know a “Count William,” for whom she translated the fables, and the “noble king,” probably Henry II, for whom she wrote the lais. Her career spanned several decades. The poet Denis Piramus, believed to be writing in the 1170s or even earlier, refers to her lais and their popularity scornfully, and a reference in the Espurgatoire to Saint Malachais, canonized in 1189, provides a terminus a quo for her later work. Her lais and fables suggest that she was well educated and apparently literate in Latin, at home in the court milieu, not at times unworldly in her attitudes (but also interested in the life of a convent), and proud of her success as an author. This description might fit, among others, the abbess of Shaftesbury, the abbess of Ramsey, the countess of Boulogne, and the daughter of Waleran II, count of Meulan (now often considered the most likely candidate).5 But it has also been suggested, precisely because of the manuscript’s provenance, that Marie may have been a nun at Reading, perhaps even its abbess. If Marie had been at Reading in the late twelfth century, it would be quite in order that about half a century later the abbey should acquire or make another copy of her lais, either because its members happened to have an earlier copy to work from, perhaps even her autograph, or because they were proud of the connection, or both. This would mean that the historical reader of Harley 978 was very close indeed to Marie and might even have been her successor. The images in the lais of educated women, independent of spirit but often painfully immured, would be matched in the real world, where writer and reader walked the same cloister. Admittedly, most scholars of Marie de France seem uneasy at the identification of Marie as nun or abbess of Reading, but no one, to the best of my knowledge, has dismissed it out of hand.

Somebody should have. There is a very simple reason why Marie cannot have been the abbess of Reading: by her day there was none. Before the Conquest there had been at least one and possibly two nunneries in Reading, but when the abbey was reestablished by Henry I in 1121 it was as an all-male house. There were no nuns and therefore no abbess.6

If this were simply a matter of a single critic advancing an ill-founded argument, it would be less alarming. But the failure to challenge this hypothesis reflects a general lack of historical information among literary critics about the texts’ circulation. We are confronting a disciplinary gap. One group of scholars reads Anglo-Norman lais and another reads English ecclesiastical history, and the two remain in splendid isolation. As a result, modern scholars are a long way from understanding anything about the milieu of one particular reader, or group of readers, of Marie’s work. Critics who do not know that there were no nuns at Reading after the Conquest probably do not know very much about Reading at all. They will not know that it was very nearly dissolved for bankruptcy in the 1280s or that the bishop chastized one of its dependent priories for keeping hunting dogs and birds of prey or that it was a center for avant-garde music or that one monk ran away from the abbey and joined a gang of brigands. The word “Reading” will not conjure up a detailed vision of a specific place for them, as it did for Jamieson Hurry, whose popular histories are always well illustrated (see fig. 10 below). In the commentary on Marie de France, “Reading” is merely a tag on which to project stereotypes of monasticism.

So far, I might feel warranted to write in a tone of moral indignation. But as we pursue the variety of Harley 978, it will become apparent that blunders of this kind will be very difficult to avoid. Doubtless I have made many, just as I have in my efforts to transcribe glosses from the Digby Timaeus or Royal 10. E.4. The sheer range of material, from medical texts to hawking manuals and from musical pieces to political satires, will defeat any single scholar. The lesson to be drawn, it seems to me, is that as medievalists we need to establish protocols for much more extensive collaboration, a question I shall return to in the final chapter.

The challenge of these manuscripts is not just the range of the materials, however, but the tensions or hostilities they evoke. The gap between the hawking manual, a guide to a particular form of erotically charged conspicuous consumption, and the Song of Lewes, a panegyric for a saintly Christian warrior, is but one example. The problem becomes most acute with Royal 10. E.4. This massive legal compendium demands a significant study of canon law from anyone who hopes to read it. My own rudimentary effort, as I piece my way through a single passage, draws heavily on the assistance of friends and on preliminary course work that I did years ago as part of a conservative training offered by the Pontifical Institute for Mediaeval Studies in Toronto, whose scholars expended much time on students such as myself who must often have seemed mere dilettantes. The Institute’s commitment to meticulous and traditional scholarship, to Latinity, and to a vision of the Middle Ages as a coherent period defined by certain well-recognized intellectual traditions was a good match for the demands of texts like those in the Royal manuscript. For many, the study of canon law is sustained by a vision of rational, and ultimately benevolent, order imposed upon human chaos or, to quote the title of a study by one of its most distinguished scholars, a vision of harmony from dissonance. The marginal images in Royal 10.E.4 are, however, fundamentally at odds with these values. The bottom margin in particular offers a marvelous comic strip that runs the length of the manuscript, switching from one story to another and drawing on romances, fabliaux, saints’ lives, and miracles of the Virgin. These images seem to celebrate dissonance and the resistance to higher authority, as do many of the best modern readers of marginalia. It would be far too reductionist simply to equate the legal text of the Decretals with authority and rational order and the images with populist resistance and the unconscious, but the tensions between the two do run somewhat along such lines, and scholars committed to one have so far, for the most part, had little to say about the other. If a proper investigation of Digby 23 would require at least two scholars, one specializing in medieval philosophy and one in the chansons de geste, a proper investigation of Harley 978 would require a team, and a proper investigation of Royal 10.E.4 would require at least two scholars who were in fundamental disagreement on matters of principle. There may, then, be an important sense in which Royal 10.E.4 is unreadable in the modern world, for no single modern person will be able to embrace the contradictions it contains.

The material has imposed certain demands that may sometimes burden or irritate my readers, and I ask in advance for their patience. It has seemed to me important to capture as much information as possible about specific human beings known to have used these books. I do not wish to imply that the ones I have managed to discover, William of Winchester, who owned Harley 978, or Henry of Langley’s friend, who owned Digby 23, hold the ultimate clue to what these works really mean or that they are in any sense definitive readers. But they were readers. And if more information survived and we could find other readers, even if we could find earlier readers from the “right” century or the “right” social group—twelfth-century knights and ladies for twelfth-century chivalric poems, for example—they too, if we knew them one by one, would prove no less idiosyncratic and elusive. It is the contact between these messy people and the more rarified order offered to them in books that I wish to explore. So I have pursued my Williams and my Henrys. My reader must suffer through a good deal of biographical minutiae, labored efforts to reconstruct lost chronologies, and a litter of words like “probably,” “maybe” and “perhaps” and may still think at the end that the links between the books and the people are tenuous, the description of their reading patterns alarmingly speculative.

Second, this study is painfully incomplete. I offer a good deal of information about each manuscript and explore some of the material at fair length, but my treatment is partial, in both senses of the word. I have but a little to say about the history of glossed copies of the Timaeus. I only touch on the medical and Goliardic texts in Harley 978. I cover only some of the marvelous marginal stories in Royal 10. E.4. Nor, in general, do I offer the full, detailed textual analysis that is the glory of modern literary criticism. What I have tried to suggest is how a given collection of texts might have taken meaning in the mind of a particular reader, a real person, at a given moment. As part of this approach, I have explored the different modes of reception that might have been available and most readily brought to bear upon each manuscript: minstrel recitation, chant, or refectory reading for Digby 23(2), silent reading and fantasization for Harley 978, scholarly consultation for Digby 23(1) and Royal 10. E.4. Such an exercise is, I think, a useful contribution to cultural history and one that has considerable bearing on how we choose to read medieval texts today. But it is not a substitute for sustained close readings; it is perhaps at best a powerful disruption.

The internal diversity of these manuscripts also creates stylistic problems. Moving from one genre to another, and from one discipline to another, I have shifted tone and acknowledged different levels of proof. The voice used to discuss whether William of Winchester commissioned all of Harley 978 from the booksellers of Oxford and the voice used to discuss how he might have read one of Marie’s lais cannot really be the same. Once more, the conclusion I draw from this is that for some kinds of scholarly project, including most of those that might wish to be considered historicist, single authorship has severe limitations.

The field of manuscript studies has often been seen as an intensely conservative one, not least by its practitioners, who are much given to presenting it as a bastion of certainty against the rages of modernity and the over ingenuity of literary critics. But this is not how I would choose to justify my interest. The three manuscripts I examine offer not some absolute origin but rather a testimony to the complexity of textual production and a measure of the difference between our cultural categories and those of earlier times. They offer us, too, a measure of the gulf between the lives of medieval people and the roles their culture assigned them, whether as those who fought, those who worked, or those who prayed. By preserving traces of the activities of actual readers, who often did a little of all three, the manuscripts take us back to the complexities of human behavior and human desire, bringing us not firm answers but new questions.

Occluding the Material

In the last two decades there has been a renewed attention on the part of philosophers, historians, and literary and cultural critics to the material state in which texts are preserved and disseminated.7 Once largely relegated to an ancillary discipline whose obscure calculations could be dispensed with the moment it had fulfilled its duty and produced an accurate version of the author’s final intention, editing is now widely recognized as a field in which the historical construction of a work is brought to light. Texts, it is argued, exist only in specific material forms, or, to borrow Chartier’s phrasing in the epigraph at the beginning of this chapter, they exist only in specific kinds of material support. Although the phrase “material support” is cumbersome, it has the advantage of leaving as open as possible the question of exactly what this support is. “Material support” can refer to a good deal more than just the physical book. It might, for example, be applied to the sounds of a text that is sung or to the singer’s voice. It is to the physical book, however, that the term has most often been applied, and it makes sense to begin here, with the argument that the precise physical form of a particular manuscript or edition is a vital part of any given text’s meaning and social function.

An early and influential statement in the field of print bibliography is that of D. F. McKenzie, who compares two early editions of William Congreve and argues that it is impossible “to divorce the substance of the text on the one hand from the physical form of its presentation on the other.”8 According to McKenzie, the physical format of the 1710 three-volume octavo collected works, which was printed under Congreve’s personal supervision, provided fundamental evidence of Congreve’s vision of himself as a respectable neo-classical author. When in the same article McKenzie explained that the original 1678 edition of Pilgrim’s Progress “was a duodecimo, set in pica roman, to a measure of only 14 ems” and therefore had a short prose line suited for the less literate reader, he demonstrated how the fine detail of textual criticism could feed into social history.9 Historians have advanced similar arguments for the social significance of particular formats.10 Robert Mandrou’s study of the bibliotheque bleue established a fundamental link between the material support—in this case, cheap pamphlets suitable for sale by peddlers—and its social dissemination.11 Robert Darnton’s work on booksellers’ lists and indices of proscribed books in eighteenth-century France established a surprising connection between political radicalism and pornography, both falling under the heading of libertinage and frequently being sold and condemned together.12 The effect of cheap printed forms such as serials or mass-market paperbacks on popular reading patterns during the last two centuries has been investigated extensively.13

These claims for the fundamental importance of the material support are neither trivial nor mere commonsense; indeed, they represent a major disruption of certain fundamental assumptions subtending much of the close reading of literature and even the very category “literature” itself. Social bibliography, history of the book, textual materialism—these overlapping approaches all call into question the self-contained, self-referential, and stable literary artifact, whether the well-wrought urn of New Criticism or the closed semiotic system of structuralism. Thus Jerome McGann objects to “the contemporary fashion of calling literary works ‘texts’” on the grounds that it “suggests that poems and works of fiction possess their integrity as poems and works of fiction totally aside from the events and materials describable in their bibliographies This usage of the word text does not at all mean anything written or printed in an actual physical state; rather, it means the opposite: it points to an Ur-poem or meta-work whose existence is the Idea that can be abstracted out of all concrete and written texts which have ever existed or which ever will exist.”14 Roger Chartier’s rejection of the “ideal, abstract text” cited above runs along similar lines.15

If the ideal text is stable and unique, the material text is multiple. So far the implications of this insight for literary criticism have had perhaps their greatest impact on the study of Shakespeare. Bibliographic minutiae, once valued as evidence from which one could reconstruct a stemma and recapture “what Shakespeare actually wrote,” have now become a mark of textual multiplicity. As Margreta de Grazia and Peter Stallybrass observe: “For over two hundred years, KING LEAR was one text; in 1986, with the Oxford Shakespeare, it became two; in 1989, with The Complete King Lear 1608–1623, it became four (at least). As a result of this multiplication, Shakespeare studies will never be the same.”16 De Grazia’s and Stallybrass’s collaboration with Randall McLeod/Random Cloud/Random Clod demonstrates how apparently minor bibliographic details can problematize the categories of author, character, and work. If we return to the early printings of the folio and the quartos, we find no fixity but instead an almost scribal fluidity in which the famous “weird sisters” of Macbeth are more often “wayward” and the very identity of works such as Lear or Hamlet is in question (a fluidity McLeod extends to his own name). The bibliographic details of the early printings ultimately bring us back from “the solitary genius immanent in the text and removed from the means of mechanical and theatrical reproduction” to “the complex social practices that shaped, and still shape, the absorbent surface of the Shakespearean text”17 While strong claims for traditional recensional editing can still be made, the ultimate goal of recapturing a single authorial origin, whether of Shakespeare or anyone else, is increasingly recognized as a chimera. Fredson Bowers’s hope that in the case of Shakespeare “in the end, one man may be able to digest the widely assorted technical and critical problems and unify them into a single great work of scholarship,” leaving us a text “as close as mortal man can come to the original truth,” seems to belong to another age.18

A similar confluence of “conservative” editing (which values the unique qualities of each manuscript rather than attempting reconstruction of a lost original) with structuralist and poststructuralist critical theory has flourished in romance philology.19 Here the crucial early study is Paul Zumthor’s famous Essai de poétique médiévale of 1972. Zumthor argues that the high degree of variation between manuscript copies is an essential quality of the medieval vernacular tradition and that the differing versions of a medieval poem, whether minstrel recitations or manuscript copies, should be seen not as corruptions of one original true version but as part of a continual process of recreation and modification he terms mouvance.20 This view has led to a new respect among manuscript scholars for the work of individual scribes, glossators, and correctors.21 Since manuscripts are inherently more open to alteration than printed books, they are also more likely to be polyvalent or dialogic, so that diverse forms of representation, both of text and image, may be enclosed within a single copy.22 Stephen Nichols thus sees the “manuscript matrix” as one that brings together heterogeneous or even conflicting systems of representation:

Recalling that almost all manuscripts postdate the life of the author by decades or even centuries, one recognizes the manuscript matrix as a place of radical contingencies: of chronology, of anachronism, of conflicting subjects, of representation. The multiple forms of representation on the manuscript page can often provoke rupture between perception and consciousness, so that what we actually perceive may differ markedly from what poet, artist, or artisan intended to express or from what the medieval audience expected to find.23

The challenges posed by this conflicted multiplicity will be one of the recurring themes of this book.

The recognition that an early text exists diachronically in the different layers of its copying and glossing can also be extended to cover the text’s printed history. The tendency had long been to see the printed edition as a reproduction of the manuscript’s text, one that was either neutral or, as Didron argued, deficient. More recently we have come to recognize that the poem we read is in significant ways the product of its editorial history. By stabilizing the textual tradition and isolating “literary” texts from the diversity of their earlier circulation, traditional textual editing has produced an origin for vernacular literature. It has excerpted texts from their codices in accordance with generic categories that are central to Romantic philology, concentrating on those vernacular texts that most readily conform to the category of “literature,” secular poetry expressing the genius of a people and the creative imagination of the artist. Finally, it has grouped these works together around categories of authorship that often differ significantly from those of their original makers, whether poets, compilers, or scribes.

Unless we were to revert to the world of eighteenth-century antiquarians like Thomas Tyrwhitt, one of the first editors of Chaucer, who appears to have read the entire Roland in the Oxford manuscript just to cull information on medieval literary traditions, what we read when we read a medieval poem will be some form of printed edition—and the form matters. Medieval poetry has been shaped into modern literary canons through the visual design and interpretive apparatus of modern editions. Taking as his example the Vie de Saint Alexis and comparing various editions to the illustrated manuscripts, Michael Camille demonstrates how nineteenth-century philologists “erased all aspects of enactment—sound, sight, and sense” from poems: “Carefully classified blocks of print and their footnoted apparatus, together with clearly demarcated beginnings and endings, remade texts written in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries into nineteenth century intellectual commodities.”24 The choice of titles, the connotations of different fonts, the treatment of illustrations and musical notation, as well as the layout—all these details of print bibliography are therefore of concern for those who wish to study medieval texts. The full range of the material support of any given text across the centuries deserves attention. Why then is such attention so often wanting?

Those who edit early materials, both manuscript and print, are eloquent in their condemnation of literary critics who accept a modern edition at face value without bothering to read its apparatus or give thought to its sources. Fredson Bowers laments that many readers show less concern for the sources of an edition than they would for the pedigree of their dog, while George Whalley warns us that “without scholarship the criticism of a poem may easily become a free fantasia on a non-existent theme,” and textual scholars happily furnish examples.25 Siegfried Wenzel lays out three decades of elaborate close readings of the enigmatic Middle English “lyric” sometimes called “How Christ Shall Come,” only to show that it is no lyric poem at all but a formal division of a Latin sermon into English rhymes.26 Jerome McGann has provided numerous instances in which a modern poem that critics think of as stable turns out to involve complex textual conundrums.27 However, the same reluctance to confront the material also extends to many editors. Classical stemmatic editing brought a curiously conflicted attitude to its sources, examining them in minuscule detail only to dismiss them in favor of a lost and hypothetical original. Bowers is characteristic in describing the work of the editor as “the recovery of Shakespeare’s true text from the imperfect witnesses of the past.”28 As we shall see, this attitude pervades the editorial history of the Song of Roland, which endeavors to separate the pure, original French poem from the taint of its Anglo-Norman witness.

Various explanations might be offered for this hostility or indifference to the material support. For some, it may simply be a frustration with the myopic interests of technical bibliography, whose learning is strung up like barbed wire to keep out the general reader.29 The suspicion is particularly strong among those reading medieval works that textual criticism, paleography, and the various associated disciplines serve as a professional rite of passage, guarding the old ways and excluding the new.30 For others the transcendental text is a principle of interpretive economy: the prospect of four or more Lears will dismay those who find the mastery of the Shakespearean canon a reassuring class marker or those who make their living teaching such mastery. Some see the editorial drive for a single correct text as a reflection of a humanist ideology in which literary discrimination is a mark of gentlemanly refinement and moral rectitude.31 For McKenzie, on the other hand, those who denigrate the material or physical book do so as part of an idealistic denigration of materiality in general, as he indicates in a brief but telling reference to the almost “Platonic distinction between idea or essence on the one hand and its deforming, material embodiment on the other.”32 McGann similarly classifies New Criticism as fundamentally Idealist.33 De Grazia sees indications of disgust at the carnal disorder of the early printed text, with its thick and smelly ink reminiscent of bodily secretions, and describes the efforts to redeem the book from its physicality as reflections of an incarnational need.34 Then too, to borrow a central theme from Shakespeare’s sonnets, the enduring stability of the text is a guarantee of immortality for both writer and subject. When parchment and paper molders, it calls this vision into question. If “Le Livre is the proven talisman against death,” then the physical book is a memento mori.35

Chartier suggests another reason for the hostility to the material support when he refers to the stable text as a representation elaborated by literature itself. Here it is not immortality but social order that literature offers, a world removed from the exigencies and compromises of daily life. “Gentle reader,” the text whispers. “Listen Lordings,” it cries. But the material witnesses tell a different story, their popular circulation or mass publication revealing the social situation of many a reader to have been anything but lordly or gentle. To turn to the textual materials is to break with the imaginary community of sympathetic kindred spirits and reinsert the text in the order of economic and cultural production, to “think it through as labour.”36 It is in part the texts themselves, then, that offer the lines on which later editors will construct them, even at the expense of the material witnesses.37

With medieval texts these imaginary communities often bear strong nationalistic overtones. This is the case with two of the manuscripts I consider. The first, Digby 23, contains what is often considered the foundational text of the Old French literary canon, the poem known by its modern title as La Chanson de Roland, yet Digby 23 is an Anglo-Norman manuscript, copied and read in communities located in what is now called England. Marie de France, too, has been claimed for French literature as a writer who “gazes from the elegant window of a truly French castle upon a legendary and mythical landscape.”38 But this French castle is no less mythical, hovering somewhere between the modern French nation and the medieval diaspora where some version of romans was the language of cultural prestige but not of national union. With works like the Song of Roland or Marie’s lais, it is the perdurability of the nation and its literary heritage that is at stake, and this can only be undermined by a serious consideration of the manuscripts’ earlier social milieux.

To these varying explanations for the occlusion of the material, we must add one other: the condition of modern mechanical printing has so fused with our understanding of what constitutes a text that it has become difficult to untangle one from the other. The force of mechanical reproduction has allowed the printed text to approach both the stability of the transcendental text and the plenitude of human discourse. When I read a modern novel, I do so with an assumption so confident that I do not normally recognize it that the version I see before me is the one the author signed off on and the one that readers across the world will share. The physical accidents that distinguish one copy from another (such as whether the book is in paperback or hardback, the currency it is sold in, the nature of the cover illustrations, or whether it is second-hand) all appear trivial. The assumption of total stability can be seen clearly in the conventions of academic referencing. A footnote assumes that the essential text will be the same for all readers and distinguishes between the essential information required (which edition is being used, for example) and inessential information (such as whether the book is in hardback), which it simply omits. In this world, the materiality of the books fades before the order of print.

In most cases involving works published during the last century, the assumption of textual stability is not wildly wrong. It would be harder for McGann, McKenzie, Chartier, or de Grazia and Stallybrass to make the case for the attention to textual materials of recent authors who appear only in modern printed editions. Although, to use one of McGann’s examples, W. H. Auden’s decision to revoke “September 1, 1939” makes the editorial history of this one poem of critical moment, the majority of Auden’s poems reappear in various editions with wording, spelling, capitalization, and even punctuation that are almost identical. This relative stability is surely part of the reason those who live in a world of modern printed editions find the arguments for textual criticism first trivial and then deeply frustrating. Referring to one sanguine critic of Emily Dickinson and his assurance that the words on the page before him were the absolute poem, McGann notes that “he could not even see such problems.”39

As one moves away from the relative stability of modern printing, the challenge of textual variance becomes more pressing. The apparent stability of a mechanically printed text may on occasion be illusory (as McGann demonstrates, a reader who thinks there is no textual problem with regard to Dickinson or Auden is living in a fool’s paradise), but only a few novels or poems of the last two centuries would approach the degree of fluidity, the continual mouvance, that is the norm for vernacular texts in the Middle Ages. The stability of the modern printed text and its apparent existence as a self-contained object have set the limits of our understanding of what a text is. If we are to see the problem, we must try to understand how this has happened.

This development did not happen quickly or easily. Printed books were not inherently reliable or stable and only became so within an elaborate system of regulation. As Adrian Johns has shown, it took several centuries to move from the slippery world of pirated editions and clandestine volumes of the early book trade and establish something approaching modern copyright, in which author and text have clear and stable identities.40 Into the eighteenth century, “Unauthorized translations, epitomes, imitations, and other varieties of ‘impropriety’ were … routine hazards.”41 The tribulations of John Flamsteed (1646–1719), Astronomer Royal, at the hands of Grub Street pirates offer a case in point. Johns notes that an early modern reader “could not necessarily take for granted that something calling itself John Flamsteed’s Historia Cœlestis would be owned by Flamsteed himself as the product of his authorship.”42 In England, under the direction of the powerful Stationers’ Hall, a combination of commercial organization and government licensing gradually curtailed illicit copies and ensured reliable transmission. Only under these conditions could printed material inspire general trust, a precondition for the widespread dissemination of the new experimental philosophy to which Flamsteed was contributing.43 Once those conditions were established, however, it became very difficult to think outside them. As Johns notes, “We ourselves routinely rely on stable communications in our making and maintenance of knowledge.… That stability helps to underpin the confidence we feel in our impressions and beliefs.… Even the brisk skepticism we may express about certain printed materials—tabloid newspapers, say—rests on it, inasmuch as we feel confident that we can readily and consistently identify what it is we are scorning.”44 Reliable print was not just a prerequisite for modern ways of knowing but became inseparable from them. An author was someone whose writings had been accredited by being printed; knowledge was what could be expressed in a printed book.45 To this day the term “publication” in academic parlance essentially means printing. As print became knowledge, all that was not print ceased to be knowledge, so that both handwritten documents and speech fell increasingly into a nebulous realm of untrustworthy ephemera.

Not that print became more exclusive. On the contrary, one of the reasons it is difficult to think outside the norms of print is that print covers so much. While more prestigious texts would eventually circulate freely across much of the world in uniform and well-identified editions, cheaper forms of printed material would cover an ever wider range of social discourse. In Europe, steam-driven printing gave rise to a spate of cheap publications: posters, broadsheets, advertisements, political and religious pamphlets, billboards, journals, and newspapers, as well as popular novels, and these ventured into colloquial, erotic, and quotidian areas that had previously only been expressed in speech or private writings. By the time mechanical printing reaches its full force in the later nineteenth century, print almost seems coextensive with human discourse, as Marc Angenot demonstrates in his monumental study of the state of social discourse in Paris in a single year, 1889, a study based entirely on printed texts.46 The sheer volume of printed material, combined with its expansion into almost every area of human activity, reinforces the impression that print covers all that can be known.

In the Western tradition, the printed book sets the limits of our understanding of what a book is, and it is the printed book’s apparent self-sufficiency that may be the most difficult limit to think beyond.47 As a commodity that circulates in a marketplace of strangers, a printed book appeals to a social contract that tells the reader either exactly what the book is and who wrote it or alternatively, as in the case of generic fiction such as mysteries, westerns, or romances, what kind of a book it is. A book can indeed be judged by its cover; readers demand this much predictability. This implicit social contract is contained in the paratextual material—the title, colophon, prologue, jacket blurbs, and the like—and in the design and typography of the text itself. From the single object, one can therefore potentially reconstruct much of the book’s social status, as McKenzie demonstrates in the case of Congreve. These implicit contracts can then be assessed against the evidence of actual reading practice, the kinds of poaching and tinkering, or braconage and bricolage, that specific readers have inflicted upon their books.48 To express the problem in the terms used by Chartier, we might say that while the material support of the text can never be limited solely to its physical support in a concrete object, in the case of a printed book, the concrete object is broadly suggestive of the text’s prevailing mode of social reception.

A medieval manuscript, on the other hand, offers a readable text through a local social bond that in many cases will have left no discernible traces in the book itself.49 Devotional texts produced for lay readers were sometimes copied by the patron’s personal religious adviser, for example, who would supervise the use of the book as well its production.50 There is a strong likelihood that the Dominican friars mentioned in the special prayers added to one of the earliest English Books of Hours, the thirteenth-century de Brailes Hours, also acted as guides to the various devotional practices this small private prayer book supported.51 In this case, the surviving book might be regarded as but one instrument in a small devotional community or as an incomplete script for a devotional performance. To take a very different example, medieval love poetry seems to have deliberately encouraged the audience’s participation, casting the listeners in the role of judges while providing them with models they could draw on for their own flirtations, blurring the distinction between literary and social fictions or poem and courtly conversation.52 In each case, a complex set of skills—the ability to meditate upon a text or the ability to sing or chant verse or the ability to discuss the fine points of the art of love—was an essential part of the text’s performance but often left no traces in the manuscript itself. Our understanding of what constitutes literature, however, based as it is on the conventions of print, has predisposed us to overlook or dismiss these broader discursive circles.53 Despite the close attention given to provenance, the social networks surrounding a medieval book are generally conceived of as extrinsic to it. The meaning of a text is assessed on the basis of the surviving physical object considered in isolation. Obviously, in many cases it will be very difficult to approach a manuscript in any other way, because most provide few clues of how they might have been performed. As we shall see, however, even when these clues are abundant, as is the case with Harley 978, they are often ignored.

The Voice as Material Support

Modern bibliography has fought to call attention to the overlooked, the apparently trivial or insignificant details of a text’s physical form that turn out to play a crucial role in defining a literary work and its readership. But among scholars working with printed materials, this physical form is most often taken to refer to the book as a tangible object and to its visual appearance. This is not because social bibliographers are indifferent to the myriad ways in which a book can be performed. On the contrary, the “history of the book” that has been written during the last few decades has been equally a history of reading. For those who work in these later centuries, there has been no shortage of material. The proliferation of petits papiers and the Romantic autobiographical impulse have meant that details of daily life survive in ever greater abundance and that early modern texts can be located within a plausible and detailed history of reading and performance practices. No history of eighteenth-or nineteenth-century reading forgets the oral dimension, the importance of reading circles, salons, or young couples linked by a shared pleasure in illicit books.54 Nevertheless, private and silent reading increasingly became the norm. Reading aloud, whether in the family circle, the salon, or a theater seating two thousand, was structured around widely available texts. At all social levels, people gathered together to read books that were already bestsellers and enjoy “the public acknowledgment of a shared private experience,” Helen Small’s characterization of the immensely popular readings offered by Dickens.55 Although the readings accounted for roughly half of Dickens’s fortune, they remained, in his eyes and those of his friend and biographer Charles Kent, a slightly disreputable supplement to his printed works.56

The assumption that a book’s public performance is never more than a supplement to its private reading is fundamental to modern publishing. Dickens’s powerful dramatic readings, for example, depended on the widespread availability of standard printed editions to forge the sensibility of his listeners and provide them with common referents. These assumptions are reflected in a book’s printed form. Any edition of Dickens, from the first serial installments on, serves in the first instance as a text that one person can read silently and then, and only occasionally and often after some physical preparation, as a script for public reading.

The conventions governing medieval manuscripts are very different. First, silent reading cannot be assumed. The habit of silent reading was rare even in monastic communities before about A.D. 1000 and only gradually spread outward to clerics and then lay people, and from Latin texts to vernacular ones.57 As late as the fourteenth century, there seems an element of novelty in Chaucer’s depiction of himself sitting “as dumb as any stone” when he retires to read. To use Didron’s phrase, a manuscript must be recognized as a sung object, and singing covers a wide range of activities from solemn chanting to private mumbling. Furthermore, the conventions that now permit us to distinguish between a play script, a novel, and a piece of sheet music were yet to be defined. Musical notation was only partially developed, and few could read it, so medieval songs were not necessarily distinguished in manuscript from lyric poems. This means that a large body of medieval poetry, including the lais, romances, and chansons de geste, as well as short forms like the ballade, rondeau, or virelai, now exist in limbo as far as performance history is concerned, and in their own day may well have been presented in a variety of ways as manuscripts passed from one group of users to another.

These claims for the importance of the oral aspect of medieval works are scarcely new. Paul Zumthor asserts that a medieval text is only the occasion for a vocal act.58 J. A. Burrow compares medieval books to a modern musical score.59 Walter Ong argues that, in comparison to print culture, “manuscript culture felt works of verbal art to be more in touch with the oral plenum, and never very effectively distinguished between poetry and rhetoric.”60 Nevertheless, the challenges of addressing the sound of a manuscript are extreme, and the editorial and critical treatment of medieval texts has often failed to meet them, so that the vocalization of medieval texts has all too often been ignored, normalized, or consigned to unexamined stereotypes. Here too the mental habits induced by print have been harder to shake than is generally realized.

There are numerous difficulties, but the most obvious and insoluble is the ephemeral nature of vocalization. It is not just that we have no audio recordings of medieval singers or storytellers; we have very few detailed contemporary reports either. The culture of the book provided few models for detailed accounts of popular oral performance. Developments in plainsong and polyphony, patterns of monastic lectio, the pious reading habits of saintly aristocrats, the power of a mendicant preacher or a court’s designated reader—these are described in some detail. But for minstrel performance we have little to go on beyond the occasional allusion in a popular sermon or the highly conventionalized references in the lais, romances, or chansons de geste themselves, one of the trickiest of sources. Reconstructing minstrel performance involves us in speculation, generalization from a handful of examples, and a literalistic reading of literary texts as if they were social reportage. Such approaches are characteristic of the great antiquarians of the eighteenth century, Joseph Ritson and Bishop Percy prominent among them, who initiated the history of minstrelsy. On many points they did the job about as well as it can be done. Since then we have culled further references, but our methods for reading them remain much the same.

This methodological crudity, which will offend the modern professional, whether historian or literary critic, may partially account for the cool reception accorded performance history. Edmond Faral’s Les jongleurs en France au moyen âge of 1910 still serves as a standard authority on minstrel performance, while more recent work has made surprisingly little impact on literary studies, at least in the field of Old French.61 In Chapter 2, I will examine some of the evidence of performance practice, asking whether it was at all likely that a full-length chanson de geste was ever performed by a minstrel, and in particular what evidence we have for the existence of sustained recitation or what Léon Gautier termed the “séance épique,” in which a minstrel held an entire hall in his sway. For the moment, I wish merely to acknowledge the difficulty of reconstructing medieval performance, while insisting on the absolute necessity of making the attempt. There is very little we will ever be able to claim we actually know about any medieval performance, but overt speculation is better than unexamined assumption.

The influence of print and its dominant mode, silent reading, may encourage us to think that questions of performance can be ignored and that it is possible to avoid the dirty work of speculative reconstruction and approach a medieval text in a neutral fashion without prejudging the way in which it was performed. The editorial history of the Song of Roland provides a particularly forceful example of why this is not so, showing how much is at stake in classifying this poem as a song. Here Chartier’s formulation, with one slight modification, once again makes the point: no medieval text existed in its day outside the material support that enabled it to be read or heard. A medieval text might have existed as a monk’s slow mumbling, as an ongoing courtly flirtation, as a regular daily ritual in a monastery or great household, or as a few snatches from a familiar story sung on street corners—but it never simply existed. Just as an eighteenth-century poem existed in some specific edition, so a medieval poem existed in some specific performance, and this performance was no less fundamental in determining what the text was.

The Edge of the Book

“The idea of the book, which always refers to a natural totality, is profoundly alien to the sense of writing.”62 So Jacques Derrida argues in the opening pages of his famous De la grammatologie. While his use of the terms “book” and “writing” continues to perplex, he suggests the extent to which our familiar habits of thought, founded upon long-standing traditions of written authority, predetermine our understanding. The “idea of the book” provides an all-encompassing frame of reference, and efforts to think outside it will inevitably falter. Whatever form of proliferating meaning Derrida evokes by the word “writing” will be difficult for us to grasp since it falls outside our familiar habits of mind. It will be as difficult for us to assess this frame of reference critically as it is for us to see air or for fish to see water. Nor is it clear to what extent this “idea of the book” to which Derrida alludes is grounded in the use of actual physical books at all. Is this sense of totality, the “idea of the book” as an idea of intellectual closure, linked to the salient visual totality of neatly laid-out pages bound between two covers, the books that let us always feel with our right hand where the end is as we read them? Is the idea of the book based on the use of the codex? No immediate answer is available. Historians have identified the development of literacy, the shift from roll to codex, the development of print, and the development of mechanical print as possible sources for profound epistemological shifts, and often described these shifts in remarkably similar terms, but they have been reluctant to compare accounts.63 But even if the idea of the book did not originate with the codex, it clearly drew reinforcement from it.

For medieval Christianity, the book was the fundamental symbol of a universe that was ordered, filled with meaning, and enclosed within fixed limits. The metaphor of the book was ubiquitous, and increasingly, as the codex became the dominant form of textual preservation, the book was visualized specifically as a bound volume rather than as a roll or set of tablets.64 While the mechanical advantages of the codex (chief among them that it could use lower quality parchment and permitted easier consultation of specific passages) must have played a significant role in its increased use, it was its association with Christianity that made it respectable. As Yvonne Johannot puts it, “it is the victory of Christianity in the Empire … that will assure the definitive victory of the codex over the roll.”65 Parchment itself, in which the divine word was inscribed into flesh, became a symbol of the Incarnation. The symbolic authority of Scripture was such that it became almost synonymous with its contents. For medieval Christianity, “The text is Christ as much as it is about Christ.”66 There was a fundamental association of creation, which God speaks into existence, and the Bible, the record of God’s word and “map of divine reality.”67 One thirteenth-century commentator classified the Bible and creation as two books “in which we can read and understand and learn more about God,” suggesting how completely the book had become the model for a knowable universe.68 The book was not just a symbol of the world but a way of understanding it, a mode of thought, or what Jesse Gellerich calls a “structuring principle” in Western mentality.69

This vision of the book as a complete system of knowledge bears a close (and, so far, largely unexamined) relation to the vision of print as a complete system of knowledge. Both visions are based on the premise of the stability and universality of the text, although in the first case this text refers to the single sacred text of the Bible and in the second to the innumerable but effectively identical copies of a printed edition. Both reflect an underlying order that is equally bookish. Thus Sir Thomas Browne, in his Religio medici of 1673, echoes the medieval topos of the two books of God, calling creation “that universall and publik Manuscript, that lies expans’d unto the eyes of all.”70 The use of this image by a seventeenth-century author might be taken as a symbolic moment of conjuncture when the order of the medieval book is subsumed into the order of print. Print reinforces the idea already well established in the Middle Ages that book knowledge is the only true knowledge, consigning alternate systems of understanding to a lower realm as “lore” or “folk wisdom” or “experience.” In doing so, it marginalizes a vast range of human activity, past and present, most obviously popular oral and electronic culture, but also song, ritual, dance, gesture, and visual design.

Ironically, then, it is the powerful legacy of the medieval book as an idea or structuring principle that has made the fluidity and acoustic and visual multiplicity of specific medieval books so difficult for us to recognize. We have read medieval texts as if they belonged to the world of print, divorcing the works from their codicological context and thus from the music and conversation that once surrounded them, from their institutional situation, and from the lives they helped shape. In this way we have transformed these works into the isolated verbal icons of late print culture. The world of print is now deeply challenged, however, and the confident assumptions with which we once approached a text, dispensing with any consideration of its material support, are now becoming untenable and thus apparent.71 Electronic texts are recapturing something of the openness that characterized medieval manuscripts. As early as 1989, Bernard Cerquiglini suggested that we might find in the multidimensional and dialogic computer screen a counterpart to the fluidity of medieval writing, and in the last few years a spate of electronic editions has begun to fulfill this prophecy.72 And even the category “writing” may be too restrictive, overdetermined by the conventions that identify knowledge with that which can be captured in alphabetic graphisms. Digitalization is now expanding the range of writings, reducing pictures, sounds, and printed words to a common mathematical denominator. Music, which was harmony but never knowledge, is now information; its substance in the new electronic order is the same as that of typography. This may invite us to reconsider the extent to which we have consigned the musical dimension of early texts to oblivion not as unknowable (although indeed it is difficult to know much) but as insignificant. And in a world of intimidating new literacies, our dependence on “liveware,” the friends who get us up and running, may help us understand the supporting role of earlier textual communities in making a book readable. This social transformation may make it both possible and useful to understand something of the textual materialities that came before us. Perhaps the end of the “Book” has made books visible.

Have we truly come to the end of the book? It has often been suggested. From the 1960s on, there have been recurring laments that book culture is giving way to electronic noise. “If we pose the question of the viability of the book,” wrote George Steiner in 1972, “it is because we find ourselves in a social, psychological, technical situation which gives this question substance.”73 Others have greeted the new tomorrow with rapture. According to Brian Boigon, “People are watching more television than reading books, yet a bunch of academics missed those important ABCs on entertainment that Ed Sullivan used to give away every Sunday night. Let’s face it, Disney and Nintendo have taken most of the attraction away from the educational system in North America.”74 Most of us hover somewhere between. Derrida’s frustratingly elusive account in the opening chapter of Grammatology captures the ambivalence of our situation. Derrida writes under the millenarian slogan “The End of the Book and the Beginning of Writing” and alludes to the “death of the civilization of the book”:

It is therefore as if what we called language could have been in its origin and in its end only a moment, an essential but determined mode, a phenomenon, an aspect, a species of writing. And as if it has succeeded in making us forget this, and in wilfully misleading us [à donner le change], only in the course of an adventure: as that adventure itself. All in all a short enough adventure. It merges with the history that has associated technics and logocentric metaphysics for nearly three millennia. And now it seems to be approaching what is really its own exhaustion; under the circumstances—and this is no more than one example among others—of this death of the civilization of the book, of which so much is said [dont on parle tant] and which manifests itself particularly through a convulsive proliferation of libraries.75

Perhaps we really are living on the edge of a total transformation of consciousness, a liminal situation that can only be understood partially, intermittently, and through the sallies of avant-garde philosophy. But even as Derrida evokes this millenarian transformation, the end of the book, the beginning of writing, he undercuts it, distancing himself from technological determinism, launching his paragraph from the starting point “as if” and reducing the commentary on this alleged death to predictable chatter with the dismissive occupatio, “of which so much is said.”76 So Derrida distances his metaphysical critique from historical causality and historical time—the end of the book is not the year 1967. Historians, on the other hand, have provided any number of precise moments for a decisive technological and epistemological break. The trouble is they have provided too many. Some point to the alphabet, some to the codex, some to the rise of textual communities, some to scholasticism, some to print as the key technological innovation that established book-based rationalism. Since we do not yet agree on when the “civilization of the book” began, we cannot expect a simple consensus on whether it is coming to an end.

Even if we can say with conviction that “the civilization of the book” is approaching its own exhaustion, or “the culture of print” is now deeply challenged, or that “the borders of what we call a text” are now in question, or that the adventure that linked certain technologies to “logocentric metaphysics” is coming to an end, it is not clear how these various transformations are connected, what they will mean, or how far we remain imbricated in the older orders of thought. For my purposes, however, it will be enough if the uncertainty about the future of our book-based culture helps us do better justice to the sung and drawn objects of the past.