Читать книгу Sumo for Mixed Martial Arts - Andrew Zerling - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1 Sumo Wrestling Overview Introduction

Suddenly after an intense staring contest, two huge men powerfully collide in an earthen ring. They are thickly muscled, flexible, highly trained martial artists; they are sumo wrestlers (rikishi). The initial collision of two rikishi can generate an incredible one ton of force or even more. All other things equal, the bigger rikishi usually wins. But rarely are all other things equal. Throughout sumo’s history there have been smaller rikishi who, with the proper technique, have toppled mountain-like men. A sumo historian once said the earthen ring where sumo takes place (dohyo) is circular to help a smaller rikishi angle away from a larger rikishi. This allows for more interesting matches, and it also shows that in some ways, sumo roots for the underdog.

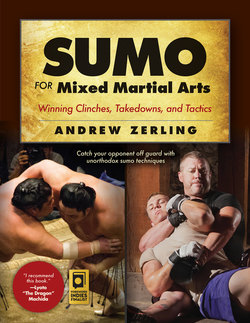

Japan’s ancient and popular martial art is greatly overlooked in the West. This book focuses on sumo’s winning moves, with special emphasis on how smaller players can win against larger players. Because sumo techniques allow a small rikishi to take down larger rikishi, there are clearly benefits in sumo for other martial arts, particularly in mixed martial arts (MMA) and other grappling arts. Modern MMA grew mostly out of jujitsu, and sumo can be seen as the root of jujitsu. Sumo, then, is ultimately one of the major roots of modern MMA. Sumo and modern MMA may look vastly different, but if it were not for the great technical fighting advancements of ancient sumo, there probably would be no MMA as we know it today.

Sumo wrestling predates jujitsu by many centuries.1 Sumo goes back about fifteen hundred years, while the first recorded jujitsu school was not formed in Japan until about five hundred years ago. Considering that sumo was an integral part of the Japanese culture for many centuries before the numerous refined empty-hand techniques of jujitsu were introduced, it would be logical to think sumo had a strong influence in the development of jujitsu.

Sumo can been considered the earliest codified form of jujitsu. Many of the kimarite, sumo’s winning moves, are similar to modern-day jujitsu and judo techniques. They also have similar names. Sumo’s one-arm shoulder throw, ipponzeoi, has a counterpart in jujitsu’s full shoulder throw called ippon seoi nage. Sumo’s koshinage, a hip throw, is similar to jujitsu’s o-goshi or full hip throw, and the same goes for sotogake, sumo’s outside leg trip, and jujitsu’s kosoto-gake, or small outer hook.

Sumo can be seen as one of the oldest and most primal and powerful of the Japanese martial arts. So it is not hard to understand why we may view sumo as the root of jujitsu. Some other martial arts, such as judo, aikido, and Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ), are all modern-day forms of jujitsu,2 each having different objectives and associated techniques that have changed over time to coincide with those objectives.

Some well-known martial artists have studied sumo. The founder of judo, Jigoro Kano, studied not only jujitsu but also a great variety of martial arts, including sumo, to help formulate his modern-day judo.3 When Kano wanted to beat a competitor, he would study everything available, along with sumo techniques and even training books from abroad. Early on, Kano used his knowledge of a sumo shoulder-throw technique to help him create the shoulder-wheel throw (kata-guruma), which is similar to Western wrestling’s fireman’s carry. He used this new throw to defeat a tough opponent. Kano collected nearly one hundred transmission scrolls (texts containing the secrets of the system) from many different schools of martial arts, including sumo.4

In Okinawa, karate master and pioneer Gichin Funakoshi in his youth engaged in sumo-like wrestling called tegumi, which he recounts in his book Karate-Do, My Way of Life. Funakoshi mentioned in his book that he cannot be sure how much tegumi helped his karate mastery, but it definitely had a positive impact. His tegumi training helped him gain muscular strength, which is very beneficial in karate. Also, Funakoshi is certain that tegumi assisted in fortifying his will, an attribute every martial artist needs.5 Tegumi branched off in two directions: the self-defense version, karate, and the sport version, Okinawan sumo. Hence, many Okinawan karate masters also practiced tegumi.

The founder of aikido, Morihei Ueshiba, started his first real training in the martial arts with sumo. In Abundant Peace, Stevens describes the grueling conditioning Ueshiba endured during his sumo training. Even while in the Imperial Army as a young man, Ueshiba was still remarkable at sumo. Ueshiba’s early training in sumo, which focused “on keeping one’s center of gravity low,” probably had an influence on the development of aikido in his later years.6 All three profoundly influential martial arts masters, Kano (1860–1938), Funakoshi (1868–1957), and Ueshiba (1883–1969) saw the great importance of adding sumo to their martial arts training routine.7

More recently, former UFC Light Heavyweight Champion Lyoto Machida, besides being an expert in Shotokan karate and BJJ, has a strong background in sumo. Machida describes in his book Machida Karate-Do Mixed Martial Arts Techniques that his sumo training strengthened his fighting stance and base, as well as his mind.8 With his open-minded approach to martial arts training, Machida has become one of the most formidable MMA fighters of his time. Later in this book we will examine his fighting style in depth, especially his outstanding use of sumo techniques and tactics in MMA competition. Even in the modern arena of MMA, Machida saw the value of integrating some sumo into his MMA fighting game.

All three profoundly influential martial arts masters, Kano (1860–1938), Funakoshi (1868–1957), and Ueshiba (1883–1969), saw the great importance of adding sumo to their martial arts training routine.

(Left: Kano, courtesy of Uchina, Wikimedia Commons. Middle: Funakoshi, courtesy of Gichin Funakoshi, Wikimedia Commons. Right: Ueshiba, courtesy of Sakurambo, Wikimedia Commons.)

The judo/jujitsu throws full shoulder throw (ippon seoi nage) and full hip throw (o-goshi) have practically the same technique and name as its sumo kimarite counterparts one-arm shoulder throw (ipponzeoi) and hip throw (koshinage). This shows that there is a very close historical link between sumo and judo/jujitsu. There are numerous other instances of this connection—so much so that sumo could be considered the earliest codified form of judo/jujitsu.

(Upper: Ippon Seoi Nage, courtesy of bimserd, Can Stock Photo. Lower: O-Goshi, courtesy of bimserd, Can Stock Photo.)

Sumo History and Practice

Myth surrounds much of sumo’s early history. It was a violent sumo match between the gods, it is said, that created the Japanese islands themselves. Sumo’s Japanese beginnings go back about one thousand five hundred years, making sumo one of the oldest organized sports on earth. There is evidence that the precursors of the combat sport probably came from China or Korea. The earliest known record of sumo in Japan is its ancient predecessor known as sumai, which was practiced in a no-holds-barred wrestling style. Warlike sumai evolved to a more sportive sumo style of wrestling. Sumo essentially took its present style in the Edo period (AD 1603–1867).

In Japan, the first sumo matches were in religious ceremonies to pray for a good harvest, and eventually they were used as a training routine for samurai warriors. Masterless samurai warriors (ronin) even used their training in sumo matches as a way to earn extra money. Sumo had an influence in the development of many modern Japanese martial arts, and today it is the unofficial national sport of Japan. The complex system of rituals and etiquette of sumo are uniquely Japanese. It is significantly more than just two huge men wrestling. Even in modern Japanese society, rikishi are thought of as godlike heroes. Rikishi literally means “powerful man.”

The rules of Japan’s ancient martial art are not complex: the wrestler loses when he touches anything outside the ring before his opponent or when he first touches the surface inside the ring with something other than the soles of his feet. The outcome is decided in a short time (in seconds, rarely in minutes). In a small ring, in those seconds, the rikishi push themselves to the maximum, both mentally and physically.

The following are prohibited techniques in today’s sumo matches and result in loss of a match due to disqualification:

striking the opponent with a closed fistbending back one or more of the opponent’s fingersgrabbing the opponent’s hairgrabbing the opponent’s throatjabbing at the opponent’s eyes or solar plexuspalm striking both of the opponent’s ears at the same timegrabbing or pulling at the opponent’s groin areakicking at the opponent’s chest or waist

Besides the disqualifying moves listed above, almost anything else is permitted to win a match.

Before a rikishi steps onto the dohyo for a major match, he must endure much rigorous and grueling training. The young rikishi train in a sumostable under the guidance of the stablemaster and his seniors. Young rikishi live in the stable, and their training starts early in the morning with mostly basic movements. Strength, flexibility, and reflex exercises are performed countless times until they become second nature, as well as breakfalls (ukemi), which protect them when they fall. Thigh splits (matawari) are an integral part of the daily training regimen to gain suppleness in the entire body. After going through the Japan Sumo Association training school, which lasts six months, a rikishi can sit down on the ground and perform a full split with his face and chest touching the ground. This is amazing conditioning, especially because the rikishi are well known for their monstrous power and explosiveness, not their flexibility.

Even the diet, a sort of sumo stew of fish, meat, and vegetables called chanko-nabe, is well calculated. This thick meal is rich in calories and protein when eaten with a lot of white rice so the rikishi can gain weight and keep it on. The schedule in which the rikishi train and eat is the key to how they put on weight. They train in the morning session on an empty stomach as the extreme workout requires, and at noon, famished, they eat as much chanko-nabe as they can. Then they take an afternoon nap to slow the food digestion so they can rapidly gain weight. The rikishi’s physique is most efficient when it is bottom heavy, with a barrel stomach. This gives them a lower center of gravity, which makes it harder to be thrown or pushed out of the ring and also helps to keep opponents at a distance. The rikishi may appear fat, but because of their diet and intense exercise regimen they have a remarkable amount of muscle mass.

Samurai warrior, ca. 1877. In Japan, the first sumo matches were in religious ceremonies to pray for a good harvest, and eventually they were used as a training routine for samurai warriors.

(Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-14302.)

Two samurai warriors, ca. 1877. Masterless samurai warriors (ronin) even used their training in sumo matches as a way to earn extra money.

(Library of Congress, LC-USZC4-14305.)

Japanese woodcut print of sumo wrestlers in action. Print created during the seventeenth century.

(Library of Congress, LC-DIG-jpd-02569.)

Japanese sumo wrestlers, ca. 1900.

(Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ggbain-26753.)

Onishiki (1891–1941) won a ten-day sumo wrestling tournament in Japan, ca. 1915. A bottom-heavy physique like Onishiki’s makes it more difficult for the rikishi to be thrown or pushed out of the ring. Also, it helps keep the opponent at a distance.

(Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ggbain-24163.)

Sumo vs. Other Japanese Martial Arts

Professional sumo differs from other Japanese martial arts in the way that rank is awarded and maintained. In most other Japanese martial arts, rank is awarded by the successful completion of a ranking test. Rarely in the other Japanese martial arts is a practitioner demoted for continued bad competition results. Also, in other Japanese martial arts, promotion can be gained by other means of training, like forms (kata). With sumo, the rikishi is only promoted if he wins official tournament sumo matches and can easily be demoted if he loses them.

Rikishi who miss an official tournament through an injury will also be demoted badly. This forces some rikishi to wrestle with serious injuries. The rikishi’s ability to win official tournament sumo matches, normally scheduled every two months, is the sole source of his livelihood and opportunity for promotion. The result is extremely stressful training and living conditions for the rikishi. This high-stress ranking structure could be seen as similar to the one in MMA competition. In MMA, if a fighter wins a championship belt, he will usually have to defend that belt or be demoted and therefore paid less, although MMA fighters tend to have fewer matches per year than a professional rikishi.

The strict hierarchy of sumo reflects traditional Japanese values. With higher rank come higher privileges. In sumo, it does not matter what your social status is; rank is achieved only through winning official tournament sumo matches. Grand Champion Akebono states, “If you want to understand sumo, you should watch the practice instead of the tournaments. In practice you can see what a difference ranking makes. It is what sumo life is based on.”9

Also, most other martial arts competitions, especially the unarmed variety like karate, judo, and MMA, have weight divisions, unlike professional sumo. So it is not uncommon for a smaller rikishi to face a rikishi two times his size. This forces the smaller rikishi to be very technical in his fighting style to compensate. The soon-to-be-discussed rikishi Mainoumi is a prime example of this. Small but successful, he was well known for his very technical fighting style.

Unranked sumo wrestlers in training. On May 2, 1998, young unranked sumo wrestlers at the Tomozuma Stable in Tokyo end their daily workout routine with a ritualized dance that emphasizes teamwork.

(US Navy photo courtesy of M. Clayton Farrington, Wikimedia Commons.)

Professional vs. Amateur Sumo

There are many major distinctions between professional sumo and amateur sumo. Professional sumo is practiced only in Japan, while amateur sumo is mostly found in Japanese schools and to a lesser extent other parts of the world. Professional sumo has no weight divisions while amateur sumo does have weight divisions. Professional sumo is a way of life as compared to the part-time training in amateur sumo. The strength and skill in professional sumo is amazingly higher than in amateur sumo. Top amateurs would have trouble surviving against professional sumo’s higher-division rikishi.

Professional sumo matches are always performed on a dohyo while amateur sumo matches many times take place on a simple matted surface. Also, females are allowed to compete in amateur sumo, but in professional sumo, not only are females not allowed to complete, but according to Japanese religious beliefs, females are also not even allowed to touch the dohyo as this will bring bad luck to the matches. And finally, much of the traditional sumo ceremony is gone from amateur sumo.

The dream of every young wrestler is to become yokozuna, or grand champion. But most of those dreams will burst.… It’s a very harsh world.

—Wakamatsu Oyakata, sumo coach and elder10

Print of sumo wrestler, ca. 1848. Notice that this rikishi carries two swords just as the samurai did. Sumo is closely linked to samurai tradition as can be seen with the use of the samurai topknot hairstyle in sumo tradition.

(Library of Congress, LC-DIG-jpd-00715.)

Sumo’s Winning Moves

The winning moves in sumo are called kimarite. At this time, the Japan Sumo Association recognizes eighty-two types of kimarite, but only about a dozen are used regularly. In actuality more than half of sumo bouts end in victory after a push (oshi), grip (yori), or slap or thrust (tsuki). These eighty-two distinct winning moves include different combinations of gripping, pushing, thrusting, throwing, leg tripping, twist downs, backward body drops, and specialized moves. As stated earlier, kimarite are usually referred to as sumo’s winning moves or finishing moves. In fact, at the end of a sumo match, an official will actually announce which kimarite was used to win the match.

Sumo’s techniques were developed more than a thousand years ago. From the early Edo period (AD 1603–1867) there are lists that describe throws that still mirror many of the kimarite used today. The history of the kimarite goes back to the medieval Japanese era when there were the traditional forty-eight kimarite or shijuuhatte (forty-eight hands). However, in 1960 the Japan Sumo Association recognized a total of seventy kimarite. In the last three decades sumo has been internationalized in that a large percentage of rikishi in the top professional divisions are non-Japanese. The influx of foreign rikishi has influenced the techniques of sumo. Among the top influences are the following:

The holds of folkstyle and Greco-Roman wrestlingThe charge of American footballThe techniques of Korean wrestling (ssireum)Since the late 1990s, Mongolian grappling (the greatest influence)

Moves such as leg picks and rear throws out of the ring could not be explained by traditional kimarite. In response, the sumo elders studied the ancient records searching for new techniques to add to the kimarite list. In 2001, twelve new kimarite were added to make a total of eighty-two kimarite. Some of the new kimarite include rear lift out (okuritsuridashi) and underarm-forward body drop (tsutaezori), which is performed by ducking under the opponent’s armpit. Stablemaster Oyama, a walking encyclopedia of sumo, said, “Kimarite is part of sumo culture. We think of them as our treasure.”11

Sumo techniques.

(Photo © Sahua, Dreamstime.)

Overview Conclusion

In this chapter, we saw that there are solid arguments for thinking sumo is the root of jujitsu. We also considered some well-known martial artists who include sumo in their martial arts training. Then we introduced the history and practice of sumo, and finally we looked at the evolution of sumo’s winning moves (kimarite). The chapter “Sumo Wrestling Case Studies” will uncover the techniques and tactics of sumo in depth; “Sumo and MMA” will expose the technical connections sumo has within MMA; and the final chapter will illustrate sumo’s winning moves from an MMA perspective in detailed photos.

Two sumo wrestlers are performing shiko, which is executed ritually to drive away bad spirits from the dohyo before each bout. Shiko, foot stomping, is a signature sumo exercise where each leg is lifted as straight and as high as possible to the side while maintaining good posture, and then brought down to stomp on the ground with tremendous force. In training at the sumostable, shiko may be repeated hundreds of times in a row. This is amazing conditioning, especially because the rikishi are greatly known for their monstrous power and explosiveness, not their flexibility.

(Photo courtesy of Yves Picq, Wikimedia Commons.)

Two sumo wrestlers making the initial charge (tachi-ai) at each other at the beginning of a match. The initial collision of two rikishi can generate an incredible one ton or more of force.

(Photo courtesy of Gusjer, Flikr.)