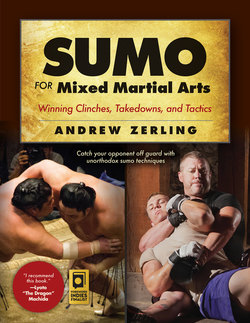

Читать книгу Sumo for Mixed Martial Arts - Andrew Zerling - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2 Sumo Wrestling Case Studies Introduction

In this chapter, we will study a specially selected group of professional rikishi for their wrestling style. As you will see, some wrestlers’ body types and fighting styles can vary dramatically, and their bouts can be quite interesting when they get together in the ring. When it comes to fighting styles in sumo, there are basically two types: traditional belt-grabbing sumo wrestling and pushing sumo wrestling. Undoubtedly, there are many rikishi who are proficient in both styles of sumo wrestling, but usually a rikishi focuses on either a pushing style or a belt-grabbing style. Techniques and tactics are presented in detail so readers might add some of these sumo moves to their own martial arts repertoire.

Case Study 1: Mainoumi—“Department Store of Techniques”

In sumo, size certainly matters, but technique matters as well. A case study in size versus technique naturally leads to the popular Japanese rikishi Mainoumi. He was five feet seven and a half inches in height and only 220 pounds, a very small person by sumo standards. Mainoumi used up to thirty-three kinds of kimarite in his wrestling days. Because of his broad use of kimarite, he was nicknamed “Department Store of Techniques” (Waza no Depaato). Mainoumi has said, “The eighty-two kimarite enhance the value of sumo.”12 Mainoumi rose to the komusubi rank, the fourth level from the top, an incredible achievement for a small rikishi in a field of giants.

Mainoumi was one of the most popular rikishi in the 1990s as his great fighting spirit and broad use of kimarite made him stand apart from the other much larger rikishi he was wrestling. For a smaller rikishi, Mainoumi’s strong judo background combined with his remarkable physical strength and agility made him a very formidable opponent. It was not uncommon for Mainoumi to win against rikishi who outweighed him by two to almost three times. A solid push from a larger rikishi would launch him in the air. He would also lose if a larger rikishi achieved a dominating hold on him. Because of this, Mainoumi would at the start of the bout feint a forward charge and then quickly jump off the line of attack. Frequently, the larger rikishi’s forward momentum was committed enough that he would fall to the ground. If that didn’t work, Mainoumi was prepared to get beside or behind his opponent and push him out of the ring or down to the ground.

Opponents started to catch on to Mainoumi’s tactics and wouldn’t commit themselves to a full-on charge at the start of the bout. The match would be downgraded to a noncommitted pushing contest. This was a contest Mainoumi couldn’t win, so he would slip or jump to his opponent’s side or back. He had plenty of strength and leg techniques to throw opponents once he was in a dominant position. Mainoumi was most vulnerable when squared up in front of his opponent. This occurred often when facing other smaller, fast rikishi like him.

Mainoumi, at the initial charge, would commonly employ quick and cunning moves, shocking both the opponent and the audience. For instance, he would use an unconventional sumo wrestling technique called “deceiving the cat” (nekodamashi). At the start of the bout, a rikishi abruptly claps his hands together just in front of his opponent’s face without touching it. The objective of this technique is to cause the opponent to close his eyes for a moment and distract him briefly, giving an advantage to the hand-clapping rikishi. This technique can be risky as, if it fails, it exposes the rikishi to his opponent’s onslaught. The hand clapping is not that difficult. The hard part is how the opponent’s brief distraction is instantly leveraged to gain the advantage. However, this trick will probably work only once on a particular opponent, as he will be expecting it the next time.

The mawashi is the belt worn by the rikishi. “The law of the ring” is that the one who dominates his opponent’s mawashi with a controlling grip will almost certainly win the match. Mainoumi considered his opponent’s mawashi his “lifeline”: if he did not grip it, he would lose. Mainoumi has said that where you grab the mawashi determines how you can turn or throw your opponent. The mawashi grip gives the rikishi the greatest leverage.

According to Mainoumi, “The worst scenario for a small rikishi is having to face a strong head-on charge. If this happens he will be overpowered and pushed out instantly. This is the most dangerous thing. To absorb the bigger rikishi thrusting, he can pull back his shoulder quickly and weaken the power of the attack. You have to be innovative. Respond flexibly in order to cope with a bigger foe.”13 To be innovative and flexible, the martial artist must dig deep into his technical repertoire to unearth appropriate solutions to the problems presented.

A prime example of Mainoumi’s advice can be seen in the November 1991 match he had with Akebono (Chad George Haheo Rowan). At more than five hundred pounds, Akebono was over twice Mainoumi’s weight and, at six feet eight inches, he was much taller. Mainoumi won the match by using a kimarite that had not been used in twenty years in a major tournament, a move judged by most observers to be a triple-attack force out (mitokorozeme) but that was officially judged an inside leg trip (uchigake). They are both leg techniques, which Mainoumi prefers, as they are an effective way for small rikishi to take down massive opponents.

Two sumo wrestlers with a referee. Color woodcut. Nineteenth century.

(Photo courtesy of Fae, Wikimedia Commons.)

Sumo wrestler Mainoumi.

(Photo courtesy of FourTildes, Wikimedia Commons.)

Case Study 2: Akebono—Grand Champion, Yokozuna

Akebono, a Hawaiian, was a very formidable opponent. In 1993 he became the first foreign-born rikishi promoted to yokozuna, the highest rank in sumo. Akebono was a powerful and longtime yokozuna. His reign in that rank lasted almost eight years. He used all of his incredible physical attributes to his advantage. His very strong and long arms were merciless when pushing or thrusting into an opponent, sometimes knocking rikishi out of the ring with just one or two movements. Akebono could practically not be beat if his opponent failed to secure a grip on his mawashi. Also, his balance was excellent compared to many other very large rikishi. Akebono said, “They [a lot of people] don’t realize how much hard work, learning and determination you got to put in. Not even Michael Jordan was great right away.”14

Akebono told National Geographic, “People see these big fat guys tossing each other around the ring, and it’s hard to understand that this is a mental sport. But the mental side, the spiritual side, is a lot more important than the body. If you can’t get yourself in the right frame of mind intellectually, you can’t win.”15

Strength alone is not enough to make a grand champion. In sumo there are three ideals: spirit, skill and body. You cannot be chosen to be a Yokozuna unless you have these qualities. So you must be a great human being as well as a great wrestler.

—Wakamatsu Oyakata, sumo coach and elder16

“Wrestling at Tokyo”: Two wrestlers engaging in a match of sumo in a ring at Tokyo, with referees standing and sitting nearby and a large crowd of Japanese in Western-style clothing watching. Hand-colored albumen photograph by unknown photographer, 1890s.

(Photo courtesy of Kükator, Wikimedia Commons.)

Yokozuna Kakuryu performing the yokozuna dohyo-iri, grand champion ring-entering ceremony, on day eleven of the 2014 May Grand Sumo Tournament in Tokyo, Japan. Date: May 21, 2014.

(Photo courtesy of Simon Q, Flikr.)

Case Study 3: Konishiki—Ozeki “Meat Bomb”

Konishiki is the first foreign-born rikishi to be promoted to ozeki, the second highest rank in sumo. Konishiki (Saleva’a Fuauli Atisano’e) is a Hawaiian like Akebono. Also, Konishiki was the heaviest rikishi ever in sumo history, at six feet one and a half inches and 630 pounds at career maximum weight. Because of his great weight the Japanese affectionately nicknamed him “Meat Bomb.” Konishiki was very close to the promotion to yokozuna, but unfortunately he never made it. The popular Hawaiian rikishi, Akebono and Konishiki, helped make sumo better known around the world.

Because Konishiki lacked technique compared to the other more experienced rikishi, he had to compensate by using his weight and power. Konishiki has said his sumo fighting style was “strictly offensive.”17 He did not try to counter his opponent’s moves defensively. By applying his monstrous size and strength, Konishiki just tried offensively to force his opponent out of the ring. His tactics worked so well they helped him achieve the much esteemed ozeki rank, the rank right before yokozuna. Although these offensive tactics usually only work for the larger rikishi, it is important to see how the larger rikishi wrestles, as this will help to show how the smaller rikishi devise ways to counter them.

Here Konishiki describes his sumo fighting style in depth: “My style is just using hands more. It’s like a boxing style, with just heavy punching. Just learning how to move my hands.”18 “My style is all power. Hitting and just powering people out. Using my hands like a football pass blocker that is my style of wrestling and I guess that is my strongest point. If I can hit a guy in the jaw and get him off balance.… Either you’re going to take a blow or I’m going to take a blow, but I’m not taking any. I’m the one who wants to give the blows. I’m trying to learn how to counter things that I’m not too good at, because when people grab my belt I have trouble. The smaller people because of the technique and because the ways that their style is different. It is like opposite of what I do.”19 It is interesting to note that Konishiki states that pushing sumo and belt-grabbing sumo are rather opposite styles. The pushing sumo style relies on physical attributes such as weight, power, and speed, while the belt-grabbing or clinching style is more of a learned technical skill.

Professional sumo wrestlers perform the ring-entering ceremony (dohyo-iri). May 2005.